Why China, India and the Dalai Lama are pushing the boundaries in Tawang

A small Himalayan district is the focus of intense diplomatic heat stemming from long-standing, unresolved border issues reignited by a planned visit from the Tibetan spiritual leader

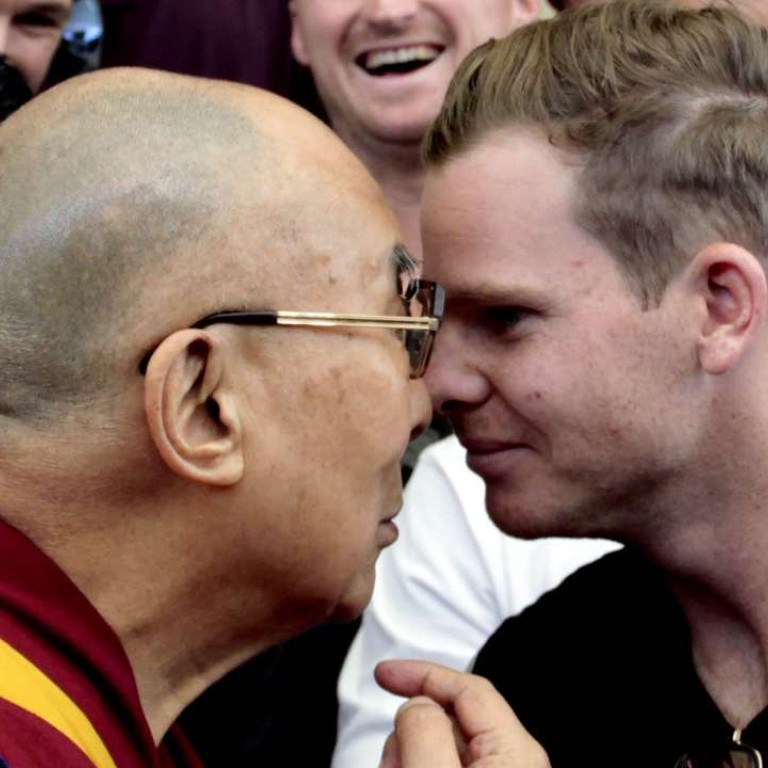

Last month, the Australian cricket team dropped by the Dalai Lama’s McLeod Ganj monastery in northern India seeking “peace of mind”. Ahead of a Test match in a fractious series with India marked by sniping between the two sides, Aussie skipper Steve Smith asked the Tibetan spiritual leader for help with his sleep. The monk rubbed his nose against his, and Smith went back to his hotel hoping for better sleep during the five-day Dharamsala Test.

The Dalai Lama’s other recent engagements have been far less reassuring for some, rubbing them up the wrong way. Beijing, for one, is losing sleep over his planned trip this week to Tawang, a small district on the western flank of what India calls its Arunachal Pradesh state in its northeast and China claims as its own South Tibet territory. This sleepy 2,000 sq km Himalayan district with less than 50,000 people has become the newest flashpoint between China and India, sparking a fresh round of jousting over their disputed border and the Dalai Lama.

Inviting the Dalai Lama “to the contested area will inflict severe damage on the China-India relationship”, foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang warned after the trip was confirmed. In matching rhetoric, minister Kiren Rijiju in Narendra Modi’s cabinet announced he would meet the Dalai Lama at Tawang. It will be a rare public appearance for a minister of Rijiju’s rank by the side of the Buddhist monk as India tends to avoid such high-profile official meetings in deference to China’s sensitivities. “India is more assertive [now],” Rijiju was quoted as telling the media.

Experts baffled by China-India border stand-off amid improving ties

Relations between China and India have become strained of late. India complains China is preventing it from bringing to book Pakistan-sheltered terrorists, blocking its entry into an elite group of nuclear suppliers and pushing ahead with infrastructure projects in Pakistan that threaten its security interests. China is wary of India’s active courting of the United States and its eagerness to involve itself in distant disputes such as the South China Sea.

On their disputed border and the Dalai Lama, whose presence in India is resented by China, they increasingly appear less inclined to abide by the discretion exercised in the past. Beijing raised a stink when Delhi allowed US ambassador Richard Verma to visit Tawang in October. In December, the Dalai Lama was invited to the Indian president’s official residence, the first such public meeting in 60 years. Last month Beijing lashed out at India for inviting the Dalai Lama to a government-sponsored Buddhist seminar.

How India and China go to war every day – without firing a single shot

The Dalai Lama is inextricably linked with the border dispute between the two Asian giants. The Tawang monastery’s historical ties to Tibetan Buddhism is an important basis of China’s claim to the 90,000 sq km India-administered Arunachal Pradesh, which lies to the south of the so-called McMahon Line drawn up by the British. It is treated as the de facto border between China and India in what is known as the eastern sector of their border. The McMahon Line was agreed to by Britain and Tibet in a secret deal in 1914 and never recognised by China, giving Beijing the legal basis to deny it recognition even while accepting the status quo.

In a rare interaction with the foreign media last month, Lian Xiangmin, director of contemporary research of the Beijing-based China Tibetology Research Centre, stressed Tawang’s links to Tibet by citing that the Tawang monastery was a subsidiary of one of the three major temples of Tibet, the Drepung monastery near Lhasa. “Tawang is a part of Tibet and Tibet is part of China. So Tawang is a part of China,” he said.

Such reaffirmations of Tawang’s links to Tibet, and by extension China, have been emanating frequently from Beijing lately. More so since the Dalai Lama in 2008, for the first time after fleeing from Tibet to India in 1959, declared Tawang was part of India. Up until 2003, he had maintained that Tawang was historically Tibetan, not Indian.

China-India-Pakistan triangle: When Xi meets Modi, a little less love this time

“The Dalai Lama’s assertion that Tawang is part of India is against the core interest of the Chinese people. He advocates Tibetan autonomy but is really seeking independence. By allowing him a platform, the India government is going back on its promise of not allowing the Tibetan government in exile to engage in activities undermining China’s sovereignty,” Wang Dehua, director of the Institute for Southern and Central Asian Studies at the Shanghai Municipal Centre for International Studies, told This Week in Asia.

Deal breaker

“Deng Xiaoping (鄧小平) had offered to make concessions in the east if India recognised China’s claim lines in the west. India lost the opportunity by not taking that offer. India refuses to compromise in the east or in the west. It doesn’t want to give away an inch of land, all it wants to do is take. That’s not how you negotiate,” said Wang. “Now even if China does allow concessions in the east, it should at least get Tawang and its surrounding areas.”

Wang echoes other voices in the Chinese establishment pressing claims on Tawang even if India gets to keep the rest of Arunachal. In a recent interview to a Beijing publication, Dai Bingguo, China’s former top diplomat who led the boundary negotiations with India for a decade to 2013, said the border dispute would be resolved if New Delhi parted with Tawang, which he called an “inalienable” part of Tibet.

India’s China policy off target, says Modi’s Mandarin-speaking ‘guided missile’

“If the Indian side takes care of China’s concerns in the eastern sector, the Chinese side will address India’s concerns elsewhere,” he said in the interview, published just before China and India held a strategic dialogue in Beijing in February. China and India, he went on to say, were standing in front of “the gate towards a final settlement” of the border and “India holds the key” to that gate.

Indian diplomats say Chinese insistence on Tawang goes against the grain of a 2005 agreement that there would be no exchange of territories with “settled populations”, and Tawang clearly fits that category. Ashok Kantha, former Indian ambassador to China, for one, says he is puzzled by the noise China is making over the Dalai Lama and Tawang.

“Pending a boundary settlement, the clear understanding since 1993 is that we will work on the basis of the Line of Actual Control (LAC). The fact remains that Arunachal is on our side of the LAC,” said Kantha. “We do not raise questions about Chinese movements in Aksai Chin even though we consider it to be part of our territory. So I do not understand when they complain about things we do on our side of the LAC. That is a departure from a fundamental agreement.”

The LAC, which works as the unofficial border, denotes the demarcation line based on actual troop control on the ground by the two sides. In the eastern sector, the McMahon Line is treated as the LAC.

What a stronger Modi means for China

Nitin Pai, a co-founder of the Indian think tank and public policy school Takshashila Institution, sees the Chinese shift of emphasis from the west to the east as part of a general pattern of hardening its position in all territorial disputes, from the South China Sea to the Himalayas. “It is linked to Beijing’s perception of a geopolitical environment which is moving increasingly in its favour,” said Pai, pointing out that China behaved no differently when the Dalai Lama visited Mongolia in November.

China called off talks with Mongolian officials over soft loans and blocked Mongolian mining trucks at the border in response to the trip. Beijing was pacified only after Ulan Bator promised not to let in the Dalai Lama ever again. Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying subsequently said: “We hope Mongolia will truly learn lessons from this incident and truly respect the core interests of China.”

Succession battle

Apart from Tibet, Tawang and Mongolia are the other possible sources of the 81-year-old 14th Dalai Lama’s successor, which also partly explains Beijing’s extra sensitivity to both.

While Tawang was the birthplace of the sixth Dalai Lama, the fourth came from Mongolia. “Tawang remains sensitive not only because it is the most significant populated area in the entire territory disputed between China and India, but also because it is inhabited by Mon people who follow Tibetan Buddhism and revere the Dalai Lama. Tawang can very well be where the next Dalai Lama reincarnates,” said Dibyesh Anand, author of Tibet: A Victim of Geopolitics, and head of the department of politics and international relations at the University of Westminster in Britain.

Traditionally, the Dalai Lama chooses the Panchen Lama to find his spiritual successor. The Dalai Lama is understood to have the ability to choose where to reincarnate and it is up to the Panchen Lama to find the child he is reborn as. The Dalai Lama selected a six-year-old boy to be his Panchen Lama in 1995. Three days later, the boy and his family were kidnapped, never to be seen again. The Chinese government then chose another six-year-old as replacement.

The Dalai Lama has repeatedly said he may be the last one, and whether he will reincarnate or not would depend on the circumstances after his death. China has made it clear that it will choose the next Dalai Lama.

Apart from China’s interest in locking in the succession in its favour after the Dalai Lama passes away, its posturing aims to isolate him while he is alive and “quarantine the Tibet issue” internationally, said Anand. “The active profile of the Dalai Lama and his followers in exile keeps Tibet alive as a political issue that can be used by India or US for their own strategic purpose. For China, a border dispute with India is a matter of strategic interest, but Tibet is about nationalist intransigence. This is a battle for public diplomacy and internal order, as well as a flexing of geopolitical muscle.” ■