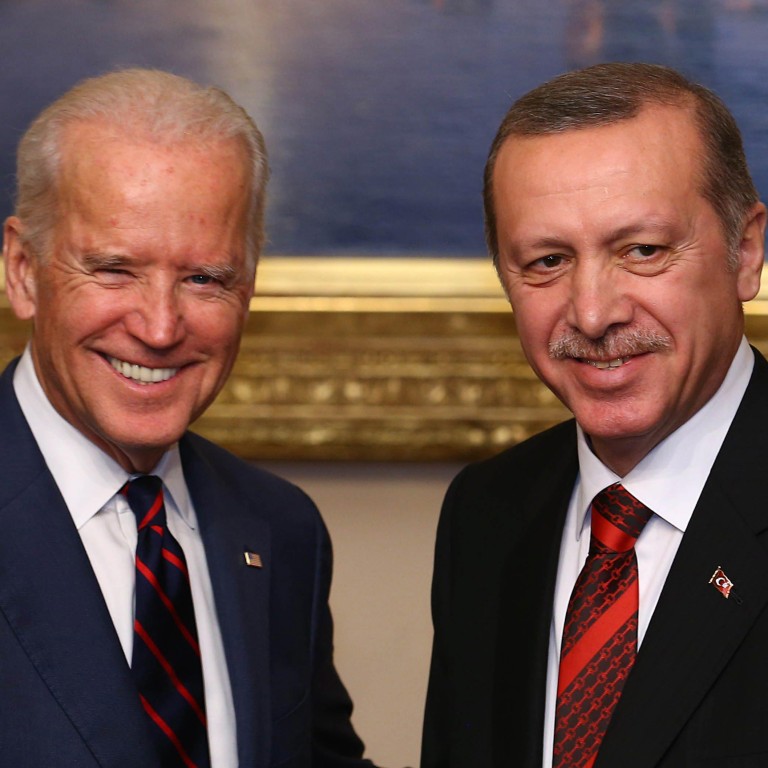

The real test of US power may be when Biden meets Erdogan, not Putin

- All eyes are on the meeting of the US president and his Russian counterpart, but it is his date with the Turkish leader that could telegraph the American approach to conflicts overseas for the next four years

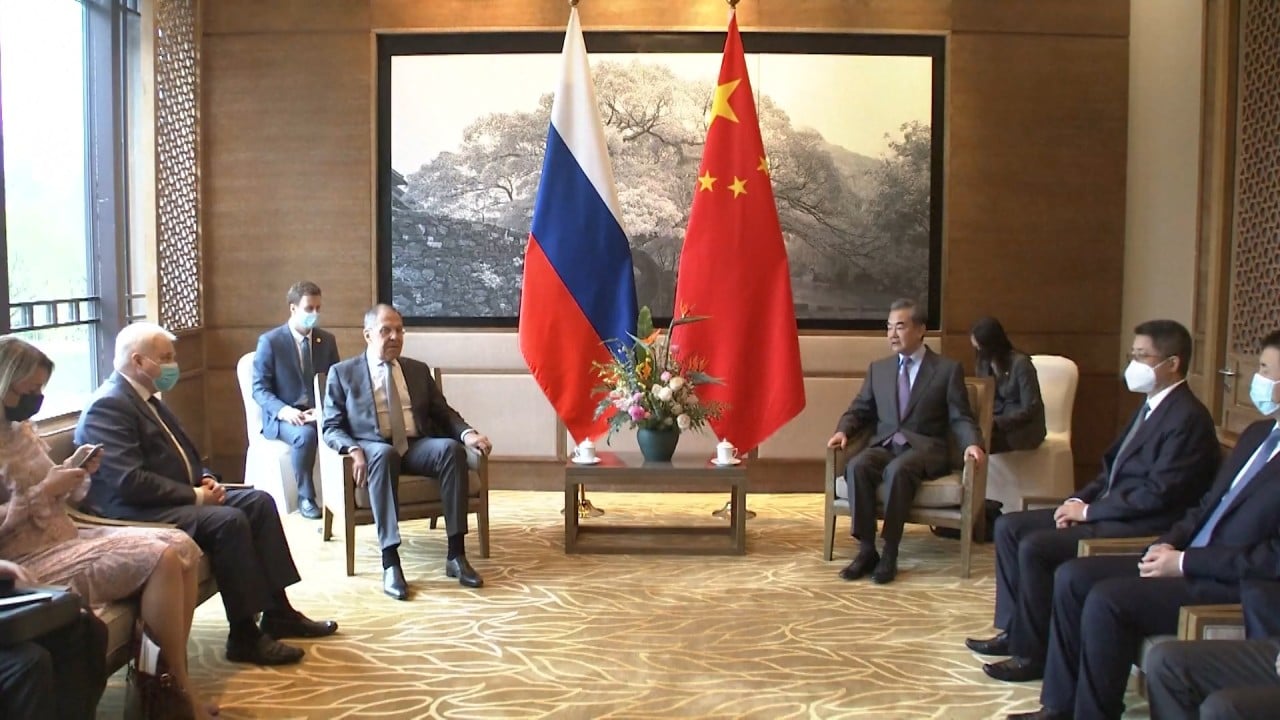

- Turkey’s flexible foreign policy when it comes to China and Russia is worrisome to the US as it seeks to rebuild alliances and reassert its global influence

That is not to say the US has not played its part in raising frictions. Biden’s move to declare the mass killings of Armenians by Ottoman Turks during World War I as genocide is just one such instance. The US president’s description of Erdogan as an “autocrat” has not helped matters.

This “balancing act” approach has another, more worrying dimension: military diplomacy via weapons sales. One of the certainties about the upcoming Biden-Erdogan meeting is that the S-400 issue will go unsolved.

The US has stuck to its guns, decreeing that sales of the F-35 will be off the table as long as the S-400 is on Turkish soil. Ankara has also dug in its heels: Even if the F-35 deal is back on, it will not turn its back on the Russian armaments.

There are several reasons for this, not least the US$1 billion per regiment price tag for the S-400 (Turkey’s S-400 deal cost it US$2.5 billion). The Russian system will also require sophisticated training and maintenance regimes, drawing both countries closer together – a crucial hedge for Turkey.

Nevertheless, the US will be negotiating from a position of strength in Brussels when the two sides meet: Turkey needs lots of help to prop up its moribund economy, and America offers it the best way out of a tailspin. That might help smooth things over, to a degree.

All this is not to say that Turkey and others have not learnt that selling weapons is a highly effective foreign policy tool. Ankara put on a highly visible – and successful – demonstration of its drone prowess in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict.

Now, any number of countries are in the shopping line for what is, in effect, a cut-price air force. These include Saudi Arabia and Poland, another Nato member.

The other lesson from this is that when the US gets its boots off the ground, there will be no shortage of countries that will be willing to test the waters and fill the vacuum.

Turkey, China, and Russia have all done so, to varying degrees, in the Middle East. Washington’s “pivot to Asia” has been a stop-start process, and interested parties, big and small, are keenly watching what will unfold.

Amid a big show of rebuilding alliances and democracy at the Nato summit, then, a key takeaway is this: for all of Biden’s talk about “values” binding nations together, opportunists will have their day.

The recurring crises in the region and the complex web of shifting alliances are testing the US’ will to reposition itself as an offshore security balancer.

The upcoming meeting with Erdogan will tell if the US will be able to impose its will without committing to troops on the ground – in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Dr Alessandro Arduino, an expert on security issues, is Principal Research Fellow at the Middle East Institute at the National University of Singapore