Hong Kong’s solution to a housing problem that doesn’t exist: dump HK$1 trillion into the sea off Lantau

- The government’s plan to create artificial islands off the coast of Lantau will cost HK$624 billion, but it habitually underestimates price tags on new projects by about 50 per cent

- Still, the entire project is unnecessary – the city is not short of building land, nor is it short of housing. So how did Hong Kong end up in such a mess?

Last week, the Hong Kong government said its planned project to create artificial islands off the coast of Lantau would cost HK$624 billion (US$79.5 billion), rather than the HK$500 billion it had previously estimated.

Let’s leave aside that the government’s first estimates habitually underestimate the price tags on its new projects by 50 per cent, which implies that the final cost of the Lantau project is likely to be at least HK$1 trillion, and very probably more.

Global recession prophets have misread the US and Chinese economies

There are a couple of more fundamental points that people have lost sight of amid all the outcry about cost:

1) Hong Kong is not short of building land.

2) Hong Kong is not short of housing.

Both these statements might appear to defy the visible evidence. So let’s take them one at a time.

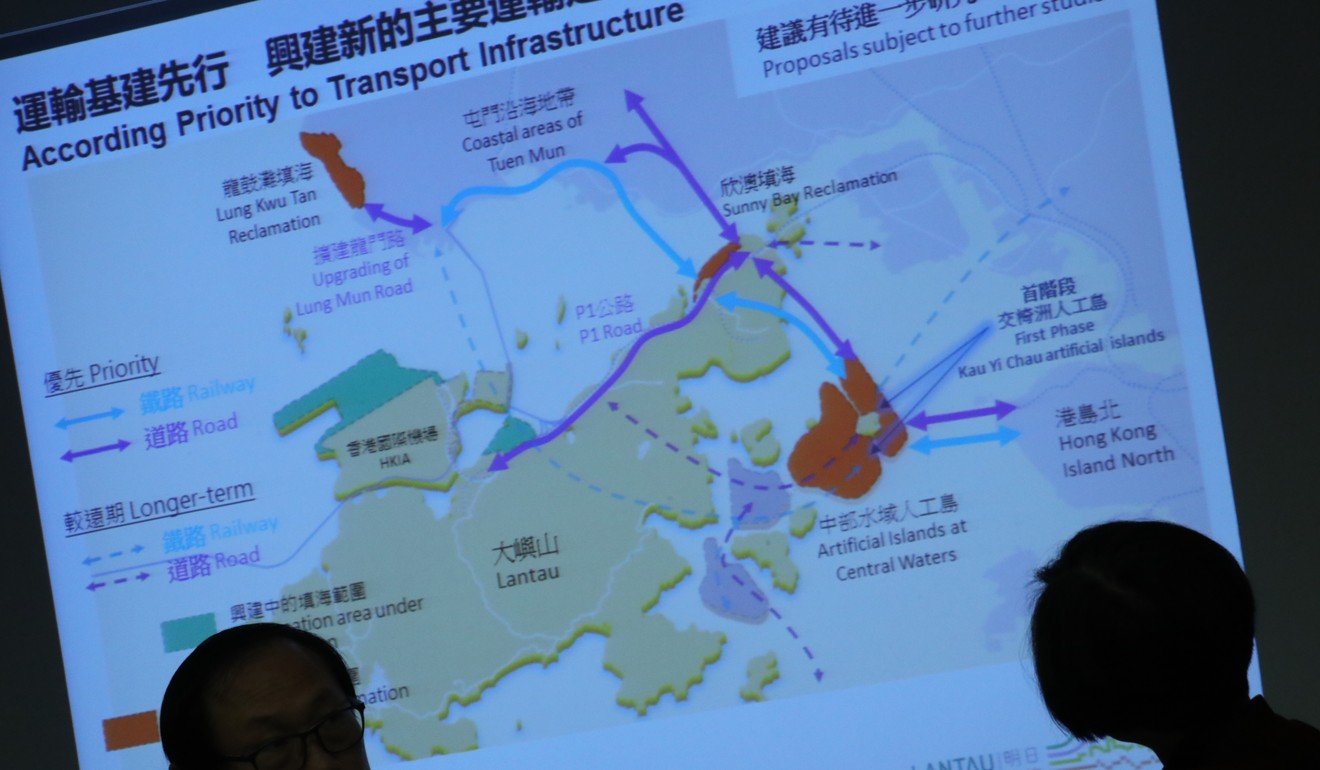

In terms of building land, the government’s East Lantau reclamation aims to create artificial islands with an area of 1,000 hectares for new housing.

That sounds like a lot. But at last count, just three of the city’s developers – Henderson Land, Sun Hung Kai, and New World – were sitting on undeveloped banks of former agricultural land in the New Territories with a combined area of 92.5 million square feet.

Converted to the metric system, that’s a total of 859 hectares – not far short of the land area the government is proposing to reclaim from the sea at such vast cost. What’s more, these land banks are eminently suitable for building on, which is why the developers acquired them in the first place.

Add in unused military bases and former industrial sites, and Hong Kong has all the building land it needs and more, without reclaiming so much as a single hectare from the sea.

As for housing, once it’s reclaimed its 1,000 hectares, the government is proposing to build 260,000 new flats on it.

Now, according to the government, as of the third quarter of last year, Hong Kong’s housing stock amounted to some 2,827,000 homes, while the city’s population consisted of 2,579,000 households.

In other words, far from suffering a shortage, Hong Kong has an excess of housing – to the tune of 248,000 surplus homes.

Three reasons to think twice about China’s stock slump

Admittedly, some of these are newly built and not yet sold. And some are old, uninhabitable, and slated for demolition.

But not that many. By even the most parsimonious estimates, Hong Kong has more than 200,000 perfectly habitable homes sitting empty, while much of the city’s population is forced to scramble for acceptable and affordable housing.

The question is: why? And how did Hong Kong end up in such a mess?

When seeking to explain distorted outcomes, it helps to look for distorted incentives. And in this case, you don’t have to look very far before finding the culprit: the Hong Kong government’s own policies.

First there is the government’s high property price policy. For years, Hong Kong officials have worked hand in hand with the city’s developers, restricting supply to keep prices sky high, to maximise the government’s real-estate-derived revenues (and developers’ profits).

(And those revenues are then artificially ring-fenced in so-called capital works funds, which officials insist can only be used to finance megaprojects like the Lantau reclamation, rather than being put to good use funding world-class education, health care or pension benefits.)

Second there is Hong Kong’s monetary system, which ties local interest rates to US dollar interest rates. That means for years the interest rates Hong Kong households have earned on their bank deposits have been less than the rate of inflation.

In other words, by keeping their savings in the bank households have been losing money in real terms. For a household sector sitting on HK$6.5 trillion in bank deposits, that’s a big loss.

As US mulls new Plaza Accord, China should learn from Japan’s fate … but not the lesson it thinks

So it’s hardly surprising that many households decided to take their savings out of the bank and put them into second flats. Many rent those flats out. At between 2 per cent and 3 per cent a year, the yield is hardly spectacular. But it is a real yield, on top of inflation, which beats by far the zero or negative real yield on bank deposits.

But many owners don’t even bother to rent out their second (or third) flats. Being a landlord to tenants is bothersome. And thanks to the government’s policies, for the last 16 years, Hong Kong residential property prices have risen by an average 11 per cent per year, year after year, regular as clockwork. As a result, many owners conclude that the extra return they can make by renting out their spare flats isn’t worth the trouble.

So the result of the government’s policies is that Hongkongers quite understandably treat homes as an investment and a reliable store of value, rather than simply as somewhere to live.

And hundreds of thousands of habitable homes sit empty. Thousands of acres of serviceable building land sit undeveloped.

And the government devises a lunatic scheme to dump the best part of HK$1 trillion of its people’s money into the sea in an attempt to solve a problem that doesn’t even exist. Welcome to Hong Kong. ■

Tom Holland is a former SCMP staffer who has been writing about Asian affairs for more than 25 years