A global China must ask itself awkward questions. Is it ready?

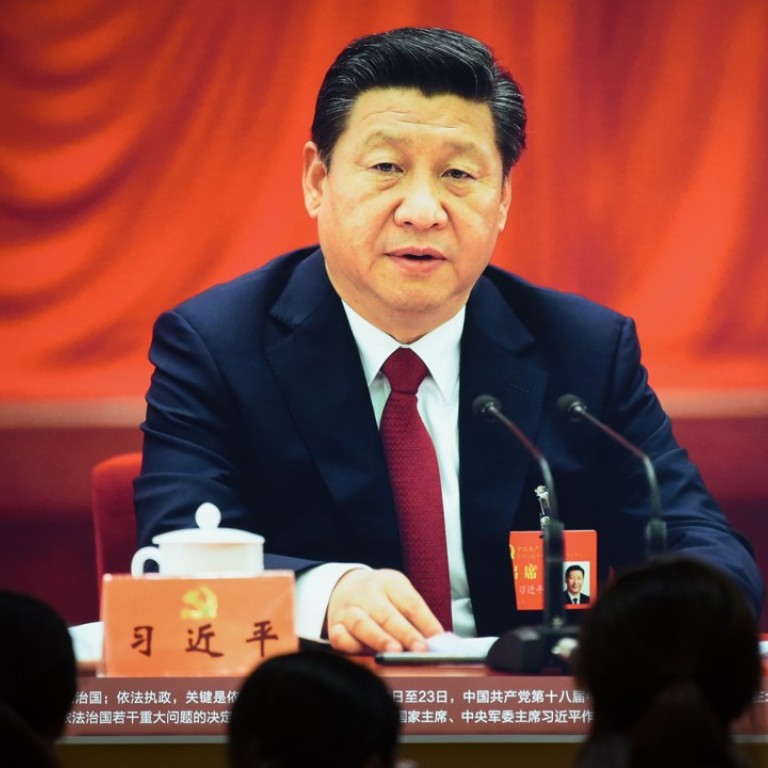

China seeks to lead the modern world. Yet its reaction to scholar Xu Zhangrun’s veiled criticism of Xi Jinping suggests its attitude to intellectuals is stuck in the past

Meanwhile, Xu’s essay is an example of a historical phenomenon that has occurred repeatedly in Chinese history, particularly in the modern era: the warning from an intellectual to the leader that the country may be on the wrong path.

Is Xi losing his grip – or taking a more flexible approach?

China’s vulnerability provided a reason for thinkers to feel urgency about new solutions, but also left gaps in the public sphere that allowed criticism to emerge clearly. In contrast, strong leadership has often meant new thinking is stifled.

Chinese intellectual life has never wanted for critiques of the state or government. What it has lacked is a regulated place for those critical voices to exist safely. When Sima Qian, the grand historian of the Han court, criticised one of the emperor’s judgments in 99BC, he was sentenced to castration.

Critics who speak truth to power and suffer the consequences recur often in Chinese history. Something else also differentiates the intellectuals who speak out in China from their equivalents in cold-war era Eastern Europe. The Andrei Sakharovs and Vaclav Havels were thinkers who were in clear opposition to the state. In China, much potent criticism has come from thinkers who have worked within the system.

Xi’s no Mao … or Deng … or Chiang – so who is he?

In the pre-war period, Jiang Tingfu became one of China’s best-known historians. In the 1930s, he also became a well-known critic of the Kuomintang government. However, Jiang was tapped by Chiang Kai-shek to hold a variety of major positions, including ambassador to the USSR, and eventually to the United Nations.

The Kuomintang was no great respecter of human rights or democracy, and its thugs gunned down cultural figures such as the poet Wen Yiduo in 1946. But it did not have an ideological prohibition on free speech as a point of principle and was on occasion able to see that criticism might be productive.

The Mao era saw a much stronger government, but it subordinated freedom of discussion to the demands of the party. In the Cultural Revolution, discussion of political alternatives to Mao’s rule were regarded as close to sacrilege. When Deng Xiaoping took power in 1978, he stressed the importance of “seeking truth from facts” and allowing thinkers to put forward their own views.

In summer 1988, an astonishing programme called Heshang (River Elegy) was shown on national television. It condemned the “peasant emperor” Mao, and advocated opening up to the “blue water” of the Pacific – a clear signal that China should become closer to the United States.

The writers of the provocative series were a pair of well-known intellectuals, Su Xiaokang and Wang Luxiang. But their criticism was not passed around like Soviet-era samizdat on badly copied carbon paper. It was broadcast for all to see on China’s most important television station, because they had a friend in the highest of places – Zhao Ziyang, the Communist Party’s then-secretary general.

Mao’s former political secretary Hu Qiaomu became the first honorary president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences when it was founded in 1977 as a think tank for clear, objective policy that would “seek truth from facts”, as Deng asked. A decade later, Hu was purging moderate academics whose supposedly “bourgeois” views offended his leftist sensibilities.

Hu Qiaomu died over two decades ago. But the legacy of his actions remains relevant today as China’s thinkers ask: can an intellectual speak objectively and not fall foul of politics? China seeks to lead in areas from technology to international development to global governance. To succeed, it will need to ask awkward questions. How can we create a system whose actions are predictable?

Why China hurts itself more than others with censorship

What constraints are there on our leadership? And what happens when China’s thinkers come up with ideas the leadership don’t like? Understanding that taking criticism well is a sign of strength, not weakness, is vital if China is to have a chance of taking a global role. ■

Rana Mitter is Director of the University China Centre at the University of Oxford and author of A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World and China’s War with Japan, 1937-45: The Struggle for Survival