Exclusive | Malaysia-Singapore Airlines – the Siamese twins set for separation: the Robert Kuok memoirs

In the third extract from Robert Kuok’s memoir, he recalls moving from shipping to the aviation industry – and a turbulent journey as chairman of Malaysia-Singapore Airlines

FROM SEA TO AIR

It was likely that some people in the government thought that it was shameful for Chinese Malaysians to run the national shipping line. When I sensed that this was their attitude, it was time for me to call it a day. Kuok Brothers eventually sold all their MISC shares and pulled out of the national shipping company completely.

In the early 1970s, the Kuok Group started its own shipping company, Pacific Carriers, in Singapore. By then I was a semiexpert on shipping. Any business can be learned through hard work, honesty and adherence to basic principles. There are qualified technical people for hire in the world. You can easily employ captains, ship engineers and architects. But most important are your businessmen.

During Pacific Carriers’ infancy, we carried mainly our own cargo. Bogasari was already very big, with a ravenous appetite for imported wheat; MSM, the sugar refinery, melted 1,600 tons of raw sugar a day and was steadily expanding its capacity. Our internal demand alone required the chartering of more than 250 vessels a year, including some time charters. I also saw in shipping the potential for a new line of business, another ball to toss, because shipping is a major world industry.

Shipping, of necessity, becomes global once you buy bigger ships. The minute you go into 20,000-ton vessels and upward, you can sail the Pacific, the Atlantic and around the Cape of Good Hope. In the past 20-odd years, we have carried ore, bulk and oil – whatever freight generates a good profit. Around the time we were launching MISC, one more job landed in my lap, this time initiated by the Singapore Government.

SAYING NO TO SINGAPORE

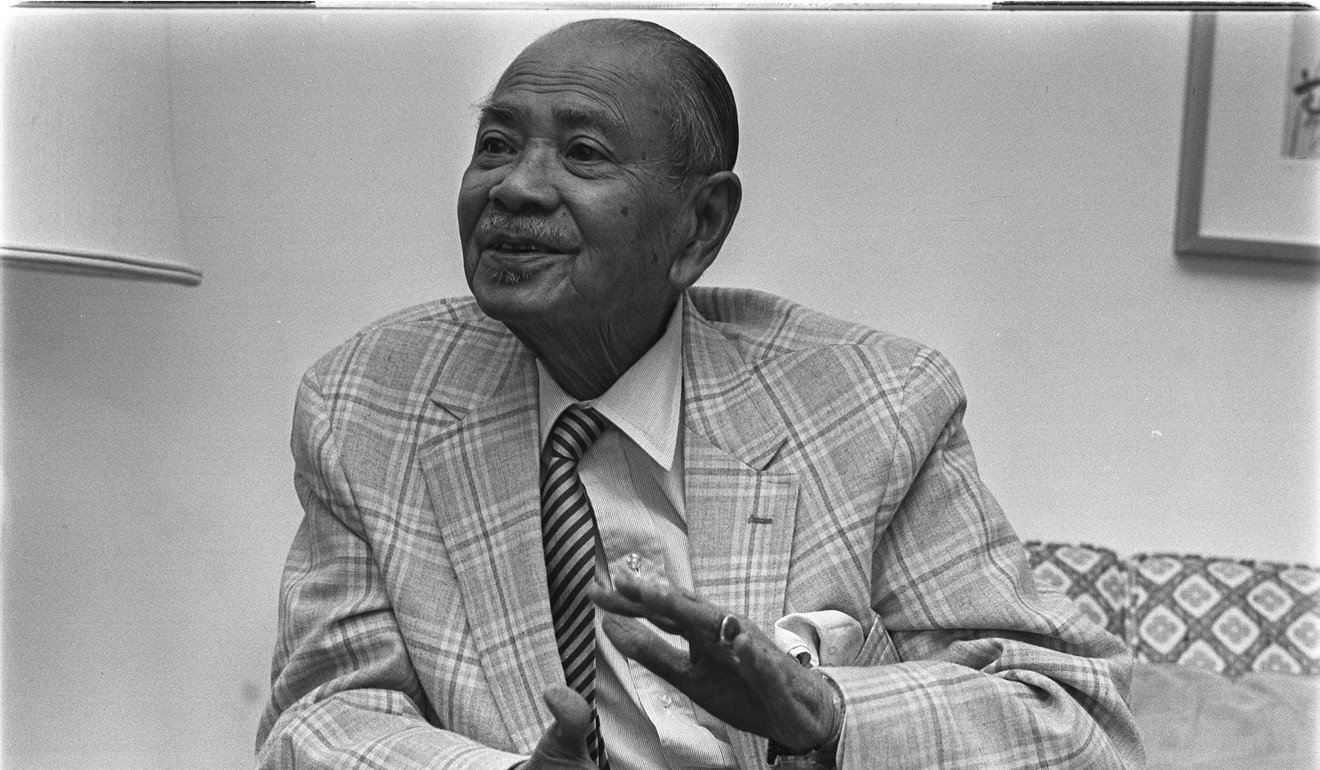

Dr Goh Keng Swee, Singapore’s deputy prime minister, asked if I would serve as chairman of Malaysia-Singapore Airlines (MSA). The Malaysian Government had proposed Dr Lim Swee Aun, the former Minister of Commerce and Industry, who had failed to get re-elected in the elections of May 1969. “We do not like him,” said Keng Swee. “But he’s not a bad fellow,” I replied. “Oh, never!” thundered Keng Swee. I said, “No, no. I’m overworked and underpaid by my own company.”

I’m overworked and underpaid by my own company

I was joking, though it was true that I hardly had a moment’s rest in those days. I told him I couldn’t take the job, because I didn’t have the time to do it justice and didn’t know the airline business. I don’t think anybody had talked to Singapore Government leaders like that. They were already known to be very fierce. As I walked towards the door, Keng Swee said, “Well, you know there are hardly any links left between Malaysia and Singapore. If you don’t want to serve, then this link will also go.” It was just like a scene in a Hollywood film. Two steps from the door, I wheeled around and asked, “Are you telling me that if I take the job, that link will be preserved?” “Yes.” Again, I felt I had no choice. “If I agree to take the job, what do I need to do?” “Simple things. First, go to see Tunku Abdul Rahman and [Deputy Prime Minister Abdul Razak Hussein] and tell them we gave you an indication that you’re acceptable to us.” “You mean I have to sell myself to my own leaders?” When he replied in the affirmative, I said, “Give me time to think about it. This is getting very sticky.”

MOTHER’S ADVICE … AND SAYING YES TO SINGAPORE

So I went away and called up mother. I explained the situation to her. She said, “Well, if you can help preserve the link, then do it, but for one term only.”

We belonged to a generation when Malaya and Singapore was one homogenous territory, and felt very strongly that ties should be preserved. So I called Keng Swee and told him that, subject to securing approval in Malaysia, I was prepared to accept the MSA chairmanship for one three-year term. A day or two later I made appointments in Kuala Lumpur and went up.

Relations between Singapore and Malaysia have always been uneasy. I saw signs even during my Raffles College days. Nine out of every 10 students from Singapore could be called city-slickers. They were keen to know who your parents and grandparents were, and whether they were rich. By and large, those students who came from Malaya had rural backgrounds. They were usually very charming and uninterested in your wealth or status in life. They were at college just to study and to make friends.

I think two-thirds or three-quarters of the top civil servants in Malaysia had been at Raffles College when I was there

Those of us Chinese from Johor had learned to live much more comfortably with Malays. There was far more give and take. Now relations between Singapore and Malaysia were strained. Singapore felt that I could play a diplomatic role; they knew that I was well connected with the Malaysian Government. I was in Raffles College when Razak was there. In fact, I think two-thirds or three-quarters of the top civil servants in Malaysia had been at Raffles College when I was there; many of the others were in school with me in Johor Bahru.

I first went to see my very close friend Tun Ismail in Kuala Lumpur. He said, “Robert, if you’ve decided to take it on, take it on, but I don’t know whether you can push it through with Tunku.”

I went to Tunku’s house at 9am and was kept waiting for about half an hour. He was a late starter. Then Tunku emerged – it was a big, rambling house – and entered the living room where I was waiting. “Ah, Kuok, Kuok. I know you. Your brother [Philip] is one of our ambassadors.” I said, “Yes, Sir.” “What’s this about?” he asked. “You want to become Chairman of MSA?” I responded, “It’s not that I want to, Tunku …”

He didn’t sound too enthusiastic about my taking on this role. He made some remarks about the problems he was having with Singapore. I kept quiet, since it was not for me to say anything. Then I prodded him a bit. “Sir, do you mind if we come back to the subject?” In the end, he said, “OK, Kuok. If you want the job, take it. It doesn’t matter to me.” So I accepted the position of Chairman of MSA.

THE JOB – AND THE BICKERING – BEGINS

The board of 15 directors comprised one chairman, four directors nominated by the Malaysian Government, another four by the Singapore Government, one director from Straits Steamship (then a British shipping company controlled by Blue Funnel Group), two directors each from British Airways and Qantas Airways and the managing director, who was on loan from British Airways.

You couldn’t have had worse bickering than between the Singapore and Malaysian Government-nominated directors

So there were six white men, eight Malaysians and Singaporeans, and myself, a Malaysian. You couldn’t have had worse bickering than between the Singapore and Malaysian Government-nominated directors. If one side raised a point and asked for a resolution to be passed, the other side would object. Each side tried to peel off the skin to see what hidden agenda existed under that resolution. The meetings would start at 9:30am, and quite often I couldn’t wind them up until 7:30pm, this at a time when I was in the thick of my sugar business. I was fortunate that my health held up. I was not just chairman of the Board. I constantly had to make peace between the directors from the two governments. I tried every fair and reasonable device I could think of. The evening before a board meeting, I would host a dinner for just the eight government directors and the company secretary.

During dinner I would work on them to make peace. “Tomorrow, these are the thorny items on the agenda,” I would explain. “Please try to understand both sides.” Sometimes, I would obtain a semblance of agreement, only to have bickering erupt at the board meeting the following day. The articles of incorporation granted each of the eight a veto, so I was running a company with eight vetoes. It was horrendous! But I stuck with it for nearly two years. I should mention that some of the conflicts I had were with one Western director in particular. When I was chairman, the managing director and CEO was David Craig, who came from British Airways. I had acrimonious exchanges with him. He tried very hard to ingratiate himself into the good books of the Malaysian directors, since the Singapore directors were very rigid and severe managers.

EXPENSIVE EUROPEAN EXPATS

Whenever David wasn’t performing, they were severe, and so he ran to the Malaysian side for protection. He found the Malaysian directors by and large convenient pillars behind which he could hide. I tried to haul him out from hiding, and our relationship soured. One day, I was in the MSA office on Robinson Road in Singapore, which was a much grander office space than my own humble sugartrading cubbyhole. David spoke to me about engaging expensive European expatriates for the airline. I asked what was wrong with engaging pilots from Burma, which at that time, under the military regime of Ne Win, was training pilots and sending some of them to aeronautical schools in England. He retorted, “Oh, no, no. Only British pilots are safe.” I pointed out that some of our commanders here were Chinese from the Malay Peninsula. He responded that there were too few. Then I suggested he try Indonesia, since Garuda was a relatively seasoned airline. He responded, “Ah, these guys land their planes in the ocean and in jungles and kill all their passengers.” I rounded on him: “Aren’t you being racist?” I noted that a Qantas or British Airways plane piloted by whites had crashed in Singapore’s Kallang Basin Airport. We had a very rough exchange. He had his agenda. When I took the job, I had no agenda whatsoever. I just wanted harmony between Malaysia and Singapore.

When I took the job, I had no agenda whatsoever. I just wanted harmony between Malaysia and Singapore

Meanwhile, the Singapore Government, which was very good with its abacus, was analysing the economics of the airline industry. They began to realise that the Malaysian domestic routes were profitmaking, but looking into the future, they could not see such air travel as big-scale business. The international airport in Singapore, and the international traffic, was really the jewel in the crown of the airline industry in the Malaysia/Singapore region. So the Singapore Government felt it would be useful to break Malaysia-Singapore Airlines into two and let each country go its own way. The Board meetings grew increasingly acrimonious. I made an appointment to see Goh Keng Swee to appeal to him to hold back his aggressive Singapore directors. I hinted that the game was getting very one-sided. I was acting as referee, but I was seeing the poor Malaysian directors slaughtered at every meeting because the Singapore directors had minds as sharp as razors. In fairness, I must say the contribution to running the airline properly and efficiently came almost entirely from the Singapore side. The Malaysian side was too subjective and often allowed their feelings to influence their comments. The writing was on the wall: the airline would separate. Now, I’m sort of a bulldog. When I want to do something, I am very tenacious. But serving as chairman of MSA was a thankless task and I was working like a slave, virtually day and night, in addition to juggling all my other balls.

TIME TO RESIGN

Moreover, I had been under the impression that this link between the two countries would be preserved. Now that the decision to split was imminent, I decided to pen a resignation letter that they could not refuse. But how do you write two lines of English words which say just that and nothing more? It took me two days to come up with those two lines. Then there was silence for three or four months.

The Minister of Finance of Singapore then was Hon Sui Sen, one of the finest men to serve as a cabinet minister from the creation of the island state of Singapore to this day. Born in Penang, he graduated in science from Raffles College about two years before I entered the school. Then came one of the nicest letters I have received in my life. It was penned by Hon Sui Sen himself, and said words to this effect: “I apologise for taking so long to reply. The reason it took so long was we could not find the right successor. This in itself is a compliment to you and what you have done for all of us. Following considerable discussion between the two governments, we have finally come up with a formula of one Chairman from each side to co-chair the board.”

They could not have asked for a more classic mongoose and cobra arrangement. The individuals they picked fought each other tooth and nail. When I stepped off, I stepped off completely. I even shut my mind to the whole matter.

The Malaysian Government chose Tun Ismail Ali, then Central Bank Governor. The Singapore side picked Joe Pillay, who had been a Singapore director of MSA from the day that I joined the board. In one sense, you could say Joe Pillay gave me the most trouble. In another sense, you could say he was the single most efficient director on the board. I admired his tremendous intellect, an intellect that had no superior in the Singapore/Malaysia region. His grasp of economics and cost accounting was fantastic.

I learned from him, watching the way he worked at his job. But he was rather highly strung. Joe is a lovely human being and a gentleman, but when it came to protecting his nation’s interest and discharging his job, he could come out unnecessarily aggressive. I remember one unpleasant exchange between Basil Bampfield, a British Airways-appointed director, and Joe Pillay at a board meeting. Joe told Basil that he should go back to British Airways and Qantas and tell them that some of the existing arrangements were unfair, and that the two airlines should make concessions to MSA. At the next meeting, Basil reported that, on behalf of British Airways and Qantas, he was authorised to agree to every request made at the preceding meeting.

I said, “This is amazingly good news. May I on behalf of all of us make a motion to express our thanks to them?” Joe Pillay interrupted, “No! It is ours by right and we should have got it long ago.” I appealed to Joe. Why cry over the past, I thought. Basil Bampfield was a fine English gentleman in an invidious job. He must have gone back and argued MSA’s case forcefully. What the two co-chairmen presided over was like a funeral. To dismantle and separate the whole company was like performing surgery on Siamese twins. It took them a long time to carry out the operation.

Robert Kuok, A Memoir will be available in Hong Kong exclusively at Bookazine and in Singapore at all major bookshops from November 25. It will be released in Malaysia on December 1 and in Indonesia on January 1, 2018