Exclusive | ‘Devils’ to friends – how China’s communists won over Malaysian PM Tunku; Hussein Onn clung to race-based politics: the Robert Kuok memoirs

In the second extract from Robert Kuok’s memoir, he recalls his access to Malaysian leaders: Tunku Abdul Rahman had a ‘bee in the bonnet’ over communism, Hussein Onn wouldn’t give up race-based politics

COMMUNIST DEVILS? PLEASE, PRIME MINISTER

Malaysia has had six Prime Ministers since independence. I have known all six. The first, Tunku Abdul Rahman, had tremendous rhythm. He was a well-educated man, having graduated with a law degree from Cambridge. If you talk of brains, Tunku was brilliant, and very shrewd. His mother was Thai, and he had that touch of Thai shrewdness, an ability to smell and spot whether a man was to be trusted or not. Tunku was less mindful about administrative affairs. But he had a good number two in Tun Razak, who was extremely industrious, and Tunku left most of the paperwork to Razak.

Tunku was like a strategist who saw the big picture. He knew where to move his troops, but actually going to battle and plotting the detailed campaign – that was not Tunku. He’d say, “Razak, you take over. You handle it now.” In that sense, they worked very well together. In my meetings with Tunku, he demonstrated some blind spots. He had a bee in his bonnet about communism. One day, when we had become quite close, he said to me, “Communists! In Islam, we regard them as devils! And Communist China, you cannot deal with them, otherwise you are dealing with the devil!” And he went on and on about communists, communism and Communist China. I responded, “Tunku, China only became communist because of the immense suffering of the people as a result of oppression and invasion. I think it’s a passing phase.” He interjected, “Oh, don’t you believe it! The Chinese are consorting with the devil. Their people are finished! You don’t know how lucky you Chinese are to be in Malaysia.” I replied softly, “Tunku, as Prime Minister of Malaysia, you should make friends with them.”

Tunku Abdul Rahman had a bee in his bonnet about communism

Years later, when Tunku was out of office, he was invited to China. Zhao Ziyang, then Premier, entertained him in the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. Tunku travelled with a delegation of 15 Chinese businessmen who were good friends of his. On his way to China, Tunku stopped in Hong Kong and I gave them dinner. Then on his way out of China, he stopped in Hong Kong and we dined again. I asked him for his impressions. All of his old prejudices had vanished! He didn’t even want to refer to them. He just said the trip had been an eye-opener. “They are decent people, like you and me,” he said. “We could talk about anything.” From then onward, you never heard Tunku claim that the Chinese Communists were the devils incarnate.

FRIENDS, NOT CRONIES

One thing I will say for Tunku: he had friends. His friends sometimes helped him, or they sent him a case of champagne or slabs of specially imported steak. He loved to grill steaks on his lawn and open champagne, wine or spirits. His favourite cognac was Hennessy VSOP. Tunku would also do favours for his friends, but he never adopted cronies.

When Tun Tan Siew Sin was Finance Minister, Tunku sent him a letter about a Penang businessman who was one of Tunku’s poker-playing buddies. It seems the man had run into tax trouble and was being investigated by the tax department, and he had turned to Tunku for help. In his letter, Tunku wrote, “You know so-and-so is my friend. I am not asking any favour of you, Siew Sin, but I am sure you can see your way to forgiving him,” or something to that effect.

Tunku would do favours for his friends, but he never adopted cronies

Siew Sin was apoplectic. He stalked into Tun Dr Ismail’s office upstairs and threw the letter down. “See what our Prime Minister is doing to me!” Tun Dr Ismail read the letter and laughed. “Siew Sin,” he said, “there is a comic side to life”. Ismail took the letter, crumpled it into a ball and threw it into the waste-paper basket. He then said, “Siew Sin, Tunku has done his duty by his friend. Now, by ignoring Tunku, you will continue to do your duty properly.” That was as far as Tunku would go to help a friend. Cronyism is different. Cronies are lapdogs who polish a leader’s ego. In return, the leader hands out national favours to them. A nation’s assets, projects and businesses should never be for anyone to hand out, neither for a king nor a prime minister. A true leader is the chief trustee of a nation. If there is a lack of an established system to guide him, his fiduciary sense should set him on the proper course.

A leader who practices cronyism justifies his actions by saying he wants to bring up the nation quickly in his lifetime, so the end justifies the means. He abandons all the General Orders – the civil-service work manual that lays down tendering rules for state projects. Instead, he simply hands the projects to a Chinese or to a Malay crony. The arms of government-owned banks are twisted until they lend to the projects. Some of these cronies may even be fronting for crooked officials.

Tunku was unnerved by the riots of May 13. After the riots he was a different man. Razak managed to convince him and the cabinet to form the National Operations Council, a dictatorial organ of government, and Razak was appointed its director. Parliament went into deep freeze. By the time the NOC was disbanded, Razak had been installed as prime minister. Tunku felt bewildered. He had helped the country gain independence and had ruled as wisely as he could, yet the Malays turned against him for selling out to the Chinese. In fairness to Tunku, he had done nothing of the sort. He was a very fair man who loved the nation and its people. But he knew that, if you favour one group, you only spoil them. When the British ruled Malaya, they extended certain advantages to the Malays.

When the Malays took power following independence on 31 August 1957, more incentives were given to them. But there was certainly no showering of favours. All of that came later, after 1969. The riots of May 13, 1969, were a great shock to the system, but not a surprise. Extremist Malays attributed the poverty of many Malays to the plundering Chinese and Indians. Leaders like Tunku Abdul Rahman, who could see both sides, were no longer able to hold back the hotheads. The more thoughtful leaders were shunted aside and the extremists hijacked power. They chanted the same slogans as the hotheads – the Malays are underprivileged; the Malays are bullied – while themselves seeking to become super-rich. When these Malays became rich, not many of them did anything for the poor Malays; the Chinese and Indians who became rich created jobs, many of them filled by Malays.

ON PRO-MALAY POLITICS

I vividly recall an incident that occurred within a few months after the May 1969 riots. I was waiting to see Tun Razak when a senior Malay civil servant whom I knew very well came along the corridor of Parliament House and buttonholed me. He asked, “What are you doing here, Robert?” I replied, “Oh, I’m seeing Tun.” He snarled, “Don’t be greedy! Leave something for us poor Malays! Don’t hog it all!” I could see that, after May 1969, the business playing field was changing. Business was no longer clean and open. Previously, the government announced open tenders to the Malaysian public and to the world. If we qualified, we would submit a tender. If we won the contract, we would work hard at it, and either fail or succeed. I think eight or nine times out of ten we succeeded.

Don’t be greedy Robert. Leave something for us poor Malays!

But things were changing, veering more and more towards cronyism and favouritism. Hints of change were there even before the riots. I was hell-bent on helping to develop the nation: that’s why I went into shipping, into steel – anything they asked of me. Even among the Malays there were those who admitted their weaknesses and argued for harnessing the strength of the Chinese. Mind you, that may have created more problems. If they had harnessed the strength of the Chinese, the Chinese would ultimately have owned 90 or 95 per cent of the nation’s wealth. This might have been good for the Malaysian economy, but bad for the nation.

Overall, the Malay leaders have behaved reasonably in running the country. At times, they gave the Malays an advantage. Then, when they see that they have overdone it, they try to redress the problem. Their hearts are in the right place, but they just cannot see their way out of their problems. Since May 13, 1969, the Malay leadership has had one simple philosophy: the Malays need handicapping. Now, what amount of handicapping?

The Government laid down a simple structure, but the structure is full of loopholes. Imagine that a hard-working, non-Malay Malaysian establishes XYZ Corporation. The Ministry of Trade and Industry rules that 30 per cent of the company’s shares must be offered to Malays. The owner says, “Well, I have been operating for six years. My par value of 1 ringgit per share is today worth 8 ringgit.” Then the Ministry says, “Can you issue it at 2 ringgit or 2.50 ringgit to the Malays?” After a bit of haggling, the non-Malay gives way. So shares are issued to the Malays, who now own 30 per cent. But every day after that, the Malays sell off their shares for profit. A number of years pass and then one day the Malay community holds a Bumiputra Congress. They go and check on all the companies. Oh, this XYZ Corporation, the Malay shareholding ratio is now down to seven per cent. That won’t do. So the Malays argue that they’ve got to redo the shareholding again. Fortunately, the ministry usually acts as a fair umpire and throws out such unscrupulous claims.

The Malays’ zeal to bridge economic gap with the Chinese bred ugly racism

It’s one thing if you change the rules once to achieve an objective agreed to by all for the sake of peace and order in the nation. But if you do it a second time, it’s robbery. Why is it not robbery just because the government commits it? And when people raise objections, it is called fomenting racial strife, punishable by three years in jail. As a Chinese who was born and grew up in Malaysia and went to school with the Malays, I was saddened to see the Malays being misled in this way. I felt that, in their haste to bridge the economic gap between the Chinese and the Malays, harmful short cuts were being taken. One of the side effects of their zeal to bridge the economic gap was that racism became increasingly ugly. I saw very clearly that the path being pursued by the new leaders after 1969 was dangerous. But hardly anyone was willing to listen to me. In most of Asia, where the societies are still quite hierarchical, very few people like to gainsay the man in charge. As in The Emperor’s New Clothes, if a ruler says, “Look at my clothes; aren’t they beautiful?” when he is in fact naked, everybody will answer, “Yes, yes sir, you are wearing the most beautiful clothes.”

THE EAR OF THE PRIME MINISTER

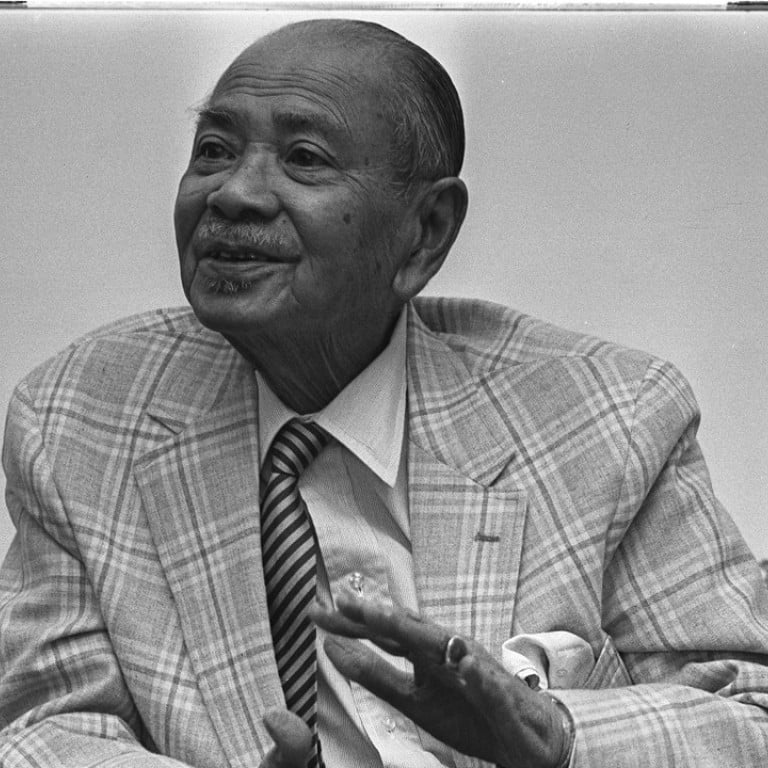

I made one – and only one – strong attempt to influence the course of history of Malaysia. This took place in September 1975 during the Muslim fasting month. Tun Razak, the second Prime Minister of Malaysia, was gravely ill with terminal leukaemia, for which he was receiving treatment in a London hospital. My dear friend Hussein Onn, son of Dato Onn bin Jafar, was Deputy Prime Minister, Minister of Finance and acting Prime Minister in Tun Razak’s absence. He was soon to become Malaysia’s third Prime Minister. I went to Kuala Lumpur and sent word that I wanted to have a heart-to-heart talk. On the phone Hussein said, “Why don’t you come in during lunch time. It is the fasting month. Come to my office at about half past one. There will be no one around and we can chat to our heart’s content.”

Hussein and I go back to 1932 when we were in the same class in school in Johor Bahru. Shortly afterwards, his father fell out with the then-Sultan of Johor and the family moved to the Siglap area of Singapore.

My father would often spend weekends with Dato Onn. Two or three years later, Hussein returned to Johor Bahru and we were classmates again at English College from 1935 to 1939. Hussein’s father, Dato Onn, did not have a tertiary education. But he read widely and was very well informed. He was a natural born politician, a gifted orator in Malay and in English. He was a very shrewd man with a tremendous air of fine breeding even though he was not from Malaysian royalty. When you were in his presence, you knew you were in the presence of someone great. Dato Onn would go on to found UMNO, the ruling party of Malaysia, and become one of the founders of the independent nation of Malaysia. He set a tone of racial harmony for the nation – and he practised it. Our families were close.

So, I went to call on his son, my old friend Hussein Onn in 1975. His office was in a magnificent old colonial building, part of the Selangor Secretariat Building. In front of it was the Kuala Lumpur padang, where, in the colonial days, the British used to play the gentlemen’s games of cricket and rugby. I climbed up a winding staircase and his aide showed me straight to his room. There was hardly another soul in that huge office complex. After greeting one another, I warmed up to my subject with Hussein very quickly. I said, “Hussein, I have come to discuss two things with you. One is Tun Razak’s health. The other is the future of our nation.” I said, “You know, Razak has been looking very poorly lately. We all know he has gone to London for treatment.” Hussein interrupted: “Tun doesn’t like anybody discussing his health. Do you mind if we pass on to the next subject?” I said, “Of course not.” I continued, “I had to raise the first subject because that leads to the next subject. Assuming Razak doesn’t have long to live – please don’t mind, but I have to say that – you are clearly going to become the new Prime Minister in a matter of months or weeks.”

“I’m listening,” he said. “Hussein, we go back a long way. Our fathers were the best of friends; our families have been the best of friends. In our young days, you and I always felt a strong passion for our country, which we both still feel. Whatever has happened these past years, let’s not go backwards and ask what has gone wrong and what has not been done right. Let’s look at the future. If there was damage done, we can repair it.”

Hussein listened patiently. I pressed on, “First, let me ask you a few questions, Hussein. What, in your mind, is the number of people required to run a society, a community, a nation with the land mass of Malaysia?” This was 1975, when the population was about 12.5 million. He didn’t reply. For the sake of time, I answered my own question. “Hussein, if I say 3,000, if I say 6,000, if I say 10,000, 20,000, whatever the figure, I don’t think it really matters. We are not talking in terms of hundreds of thousands or millions. To run a society or a nation requires, relatively speaking, a handful of people. So let us say six or seven or eight thousand, Hussein. And of course this covers two sectors. The public sector: government, civil service, governmental organisations, quasi-governmental bodies, executive arms, police, customs and military. The private sector: the economic engines; the engines of development, plantations, mines, industry.

“The leaders of these two sectors are the people I am referring to, Hussein. If we are talking of a few thousand, does it matter to the masses whether it becomes a case of racially proportionate representation, where we must have for every ten such leaders five or six Malays, three Chinese, and one or two Indians?” I continued, “Must it be so? My reasoning mind tells me that it is not important. What is important is the objective of building up a very strong, very modern nation. And for that we need talented leaders, great leadership from these thousands of people. If you share my view that racial representation is unimportant and unnecessary to the nation, then let’s look at defining the qualifications for those leaders.

“Number one, for every man or woman, the first qualification is integrity. The person must be so clean, upright and honest that there must never be a whiff of corruption or scandal. People do stray, and, when that happens, they must be eliminated, but on the day of selection they must be people of the highest integrity. Second, there must be ability; and with it comes capability. He or she must be a very able and capable person. The third criterion is that they must be hard-working men or women, people who are willing to work long hours every day, week after week, month after month, year after year. That is the only way you can build up a nation.”

I went on, “I can’t think of any other important qualifications. So your job as prime minister, Hussein – I am now assuming you will become the prime minister – your job will then be from time to time to remove the square pegs from the round holes, and to look for square holes for square pegs and round holes for round pegs. Even candidates who fulfil those three qualifications can be slotted into the wrong jobs. So you’ve got to pull them out and re-slot them until the nation is humming beautifully.”

The best brains come in all shades and colours, all religions, all faiths.

“We do not have all the expertise required to build up the nation,” I added. “But with hard work and a goal of developing the nation, we can afford to employ the best people in the world. The best brains will come, in all shades and colours, all religions, all faiths. They may be the whitest of the white, the brownest of the brown or the blackest of the black. I am sure it doesn’t matter. But Hussein, the foreigners must never settle in the driving seats. The days of colonialism are over. They were in the driving seats and they drove our country helter-skelter. We Malaysians must remain in the driving seats and the foreign experts will sit next to us. If they say, ‘Sir, Madame, I think we should turn right at the next turning,’ it’s up to us to heed their advice, or to do something else. We are running the show, but we need expertise.

You’re going to be the leader of a nation, and you have three sons, Hussein … your eldest son will grow up very spoiled

“You’re going to be the leader of a nation, and you have three sons, Hussein. The first-born is Malay, the second-born is Chinese, the third-born is Indian. What we have been witnessing is that the first-born is more favoured than the second or third. Hussein, if you do that in a family, your eldest son will grow up very spoiled. As soon as he attains manhood, he will be in the nightclubs every night because Papa is doting on him. The second and third sons, feeling the discrimination, will grow up hard as nails. Year by year, they will become harder and harder, like steel, so that in the end they are going to succeed even more and the eldest will fail even more.”

I implored him, “Please, Hussein, use the best brains, the people with their hearts in the right place, Malaysians of total integrity and strong ability, hard-working and persevering people. Use them regardless of race, colour or creed. The other way, Hussein, the way your people are going – excessive handicapping of bumiputras, showering love on your first son – your first born is going to grow up with an attitude of entitlement.” I concluded, “That is my simple formula for the future of our country. Hussein, can you please adopt it and try?” Hussein had listened very intently to me, hardly interrupting. He may have coughed once or twice. I remember we were seated deep in a quiet room, two metres apart, so my voice came across well. He heard every word, sound and nuance. He sat quietly for a few minutes. Then he spoke, “No, Robert. I cannot do it. The Malays are now in a state of mind such that they will not accept it.”

He clearly spelt out to me that, even with his very broad-minded views, it was going to be Malay rule. He was saying that he could not sell my formula to his people. The meeting ended on a very cordial note and I left him. I felt disappointed, but there was nothing more that I could do. Hussein was an honest man of very high integrity. Before going to see him, I had weighed his strength of character, his shrewdness and skill. We had been in the same class, sharing the same teachers. I knew Hussein was going to be the Malaysian Prime Minister whom I was closest to in my lifetime. I think Hussein understood my message, but he knew that the process had gone too far. I had seen a picture developing all along of a train moving in the wrong direction. During Hussein’s administration, he was only partially successful in stemming the tide. The train of the nation had been put on the wrong track. Hussein wasn’t strong enough to lift up the train and set it down on the right track.

The train of the nation had been put on the wrong track

The capitalist world is a very hostile world. When I was building up the Kuok Group, I felt as if I was almost growing scales, talons and sharp fangs. I felt I was capable of taking on any adversary. Capitalism is a ruthless animal. For every successful businessman, there are at least 10,000 bleached skeletons of those who have failed. It’s a very sad commentary on capitalism, but that is capitalism and real capitalism, not crony capitalism. Yet, I’ve always believed that the rules of capitalism, if properly observed, are the way forward in life. I know that, having been successful, I will be accused of having an ‘alright Jack’ mentality. But I am just stating facts: capitalism is a wonderful creature – just don’t abuse its principles and unwritten laws. ■

Robert Kuok, A Memoir will be available in Hong Kong exclusively at Bookazine and in Singapore at all major bookshops from November 25. It will be released in Malaysia on December 1 and in Indonesia on January 1, 2018