Opinion: Why China’s Xi might come to regret all that power

The Chinese president’s authority may have been enhanced at the congress, but the party’s connection with ordinary Chinese is not what it was under Mao, and if things go wrong, one man’s carrying the can

Perhaps it was deliberately to reassure the outside world.

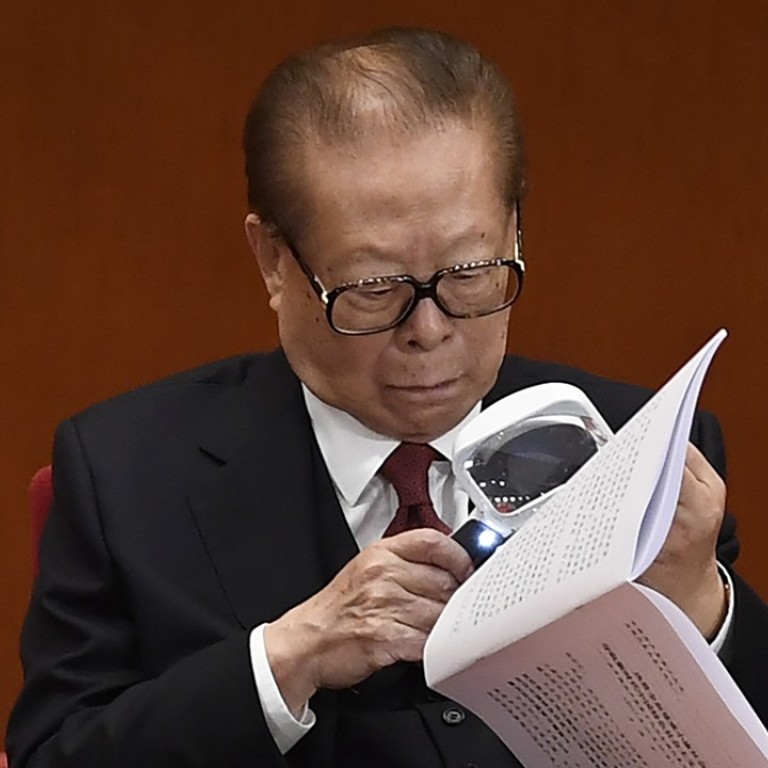

In the elite enclave of the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 18, while Xi Jinping as General Secretary was giving his epic report, his predecessor but one Jiang Zemin was gazing at his wrist watch, slumbering, sporadically yawning, and, at a couple of points, picking up a splendid white magnifying glass with inbuilt light and gazing quizzically at the speech text.

Even the most uncharitable have to admit for a nonagenarian this was a magnificent performance. After all, of all the two thousand plus people in the hall, Jiang was perhaps the least likely to ever fear Xi’s wrath. Ninety-one-year-old former elite leaders, sons of revolutionary martyrs who have been active in the party since the late 1940s, don’t offer an easy target, even from the most ambitious of new leaders.

Jiang was allowed to fumble, slumber and mumble to himself with impunity. Everyone else was under strict instructions to sit up and look alert.

WATCH: Xi Jinping’s marathon speech in 3 minutes

The fact that in the years ahead Jiang’s cameo performance might well be the one event that sticks out the most in the memories of those looking back is no bad thing. The party wanted no drama, and no excitement. It wanted, in that dreaded phrase from British politics recently, the evidence of ‘strong, stable leadership’. And being a one party, centralised system it can achieve this. There were no mishaps. Xi remained central to everything, from his epic first day perorations to the writing of his Thought into the Constitution, to his appearance on the final day with colleagues in the new leadership line up who are largely seen as obedient, able administrators.

WATCH: ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ enshrined in the party charter

That counts as success. Indeed, the Communist Party under Xi looks in rude health. But, always slightly out of direct vision, questions tend to crop up. Why the immense efforts to lead domestic and international press to pre-emptively herald this congress as a huge success, before it had even started? Why the remorseless control? Is there no space for spontaneity in Chinese politics? And doesn’t Xi look awfully exposed? Yes, he may be putting himself in all these dominating positions, but for the more Machiavellian, if things do go wrong (and there is plenty of scope for that) he is accountable at every step. Deng was the true master of keeping his fingerprints off the levers of power, while still controlling them. It gave him the crucial space to deal with the 1989 uprising. The same with Hu, whose reputation is now low, but who managed China through a hard 10 years and handed on to Xi the enormous asset of a vibrant economy. Xi is everywhere – a good thing in the good times, and a disaster when things go wrong.

Part of his prominence, manifested so clearly over this congress, was due to matters outside his and China’s hands. The calamitous situation in the US at the moment, with the lack of leadership, unpredictability and general distraction means that diplomatic spaces have opened up around China it has no choice but to fill. On climate change, global free trade, and support for multilateral deals like the nuclear one with Iran, China has been pushed into a prominence it didn’t seek – or wasn’t seeking so quickly. Even the most hawkish of Chinese foreign policy thinkers must wonder what is going on. One minute, around 2005, the US is demanding China take a more stakeholder role. The next, America is threatening to renounce many of its global commitments. So much for democracies being stable and rules based.

Analysis: what China’s leadership reshuffle means for Xi’s New Era

Xi’s power and authority have been enhanced during this congress. The simple fact that everything passed without mishap is testament enough to this. The previous congress, in 2012, threatened to descend into a shambles. There were murders, the death in a Ferrari of a top level leader’s son, rumours of a coup, and even temporary disappearances of elite leaders – Xi in particular. 2017 has been a doddle by comparison.

Opinion: Xi era beckons, but leadership rejig may not be as expected

For the average Chinese, ‘Xi Jinping Thought’ is background elite babble far away from their lives. It’s a bit reassuring – at least the politicians are busy doing their politics thing and leaving people largely alone. But it is very remote. The party has to speak in two languages – one to itself, and one to the wider world. And at moments when an ideology like this is promoted, the stretch marks reach almost to breaking point. The party is powerful and coherent in itself. But in ways in which this was not true in the Maoist era, it serves at the people’s pleasure. It has to deliver growth, a good environment, and a better lifestyle, and deliver these things quickly, to one of the toughest audiences in the world. And there are plenty of things in the next few years during this complex era of transition that could go wrong, and make this very powerful group of people with Xi at their heart looking very unpowerful indeed. ■

Kerry Brown is director of the Lau China Institute, King’s College, London