China’s welcome for Singapore PM may signal a new approach to smaller states

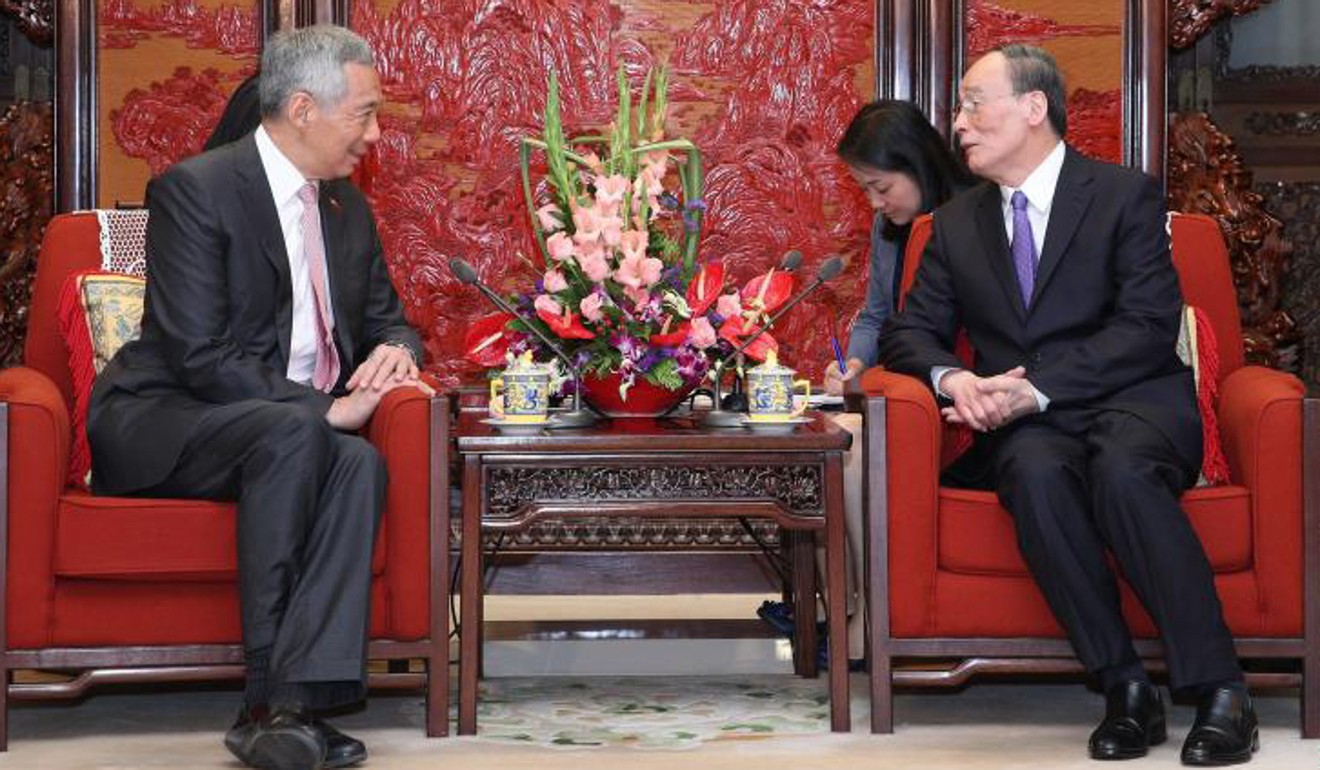

High-level reception for Lion City leader Lee Hsien Loong not only turns page on frosty relations – hopefully, it may herald end of an era in which China has sometimes acted like a giant with a superiority complex

The Chinese are well known for their elaborate protocols to welcome foreign heads of state on official visits: gun salutes, honour guards, children dancing and waving flowers, meetings and state banquets at the Great Hall of the People.

What is less well known is that subtle differences in how those dignitaries are received can give an insight into the Chinese leadership’s priorities and the levels of importance it attaches to bilateral ties with certain countries.

One curious indicator to watch for is how many top leaders – specifically, the Politburo Standing Committee members – are available to meet the visiting dignitary.

Chinese media reports have suggested Lee’s visit was sudden and unheralded. More importantly, the unusually high-level reception Lee received indicates that both countries want to turn the page on what have been strained ties over the past two years.

How a con artist rose to the heart of China’s justice system

Xi was quoted as telling Lee there were many opportunities to forge ties with Singapore in a “new historical chapter”.

A senior Chinese foreign ministry official said in a briefing for the overseas media that Lee’s visit, coming so close to the opening of China’s 19th congress next month when the country’s new leadership line-up for the next five years will be unveiled sent “an important political signal” regarding bilateral ties.

WATCH: the low down on Hong Kong’s seizure of Singaporean military vehicles

The usually hawkish Global Times newspaper suggested in its blog last week that Singapore had been forced to recalibrate its ties with Beijing because of China’s rising political and economic strength and the retreat of the United States, Singapore’s traditional ally, from the global stage, among other reasons.

Other media reports have noted that Lee’s visit to China came just ahead of his visit to the United States, scheduled for next month, suggesting a renewed effort by Singapore to become an astute player in major power politics.

Why North Korea will become a nuclear power despite pressure

The strong rebound in bilateral ties may suggest a recalibration on Singapore’s part. As a small but regionally very influential country – due to its strategic position and economic power – Singapore needs to advance with the times by dealing with China as a major power. This was evidenced by the recent debate in Singapore over whether “small states must always behave like small states”.

More importantly, the rebound could also signal a recalibration by Beijing in its foreign policies on how to treat smaller countries in Asia and the rest of the world that have been pulled into Beijing’s orbit willingly or unwillingly, because of its rising political and economic influences.

Historically, relations between major powers and smaller countries have never been easy, characterised frequently by conflicts, invasions and colonisation.

As China’s rise as a world power is set to redefine the international geopolitical narrative, whether it has got the hang of how to deal properly with smaller countries is still a matter of debate.

Over the past 20 odd years, China’s foreign policies have been predicated on forging so-called “major power” diplomacy, focusing upon its ties with the United States, Russia, and the European Union.

But soon after Xi came to power in late 2012, he started to attach great importance to ties with the surrounding countries, particularly after announcing in 2013 the ambitious Belt and Road Initiative aimed at boosting infrastructure and trade links from Asia to Africa. While the smaller countries along the Belt and Road welcome China’s investments and trade, many have understandably harboured suspicions about Beijing’s true intentions and concerns about the impact of the Chinese investments on their own ways of life, economies and cultures.

China’s leadership reshuffle: what’s behind Xi’s poker face?

On that score, China is on a learning curve regarding how to show due consideration of their feelings.

Moreover, fanned by the nationalistic sentiment at home, China sometimes acts like a giant with a superiority complex, showing imperiousness towards criticism while getting easily offended by it at the same time. This has been particularly so when the misgivings come from smaller countries, giving rise to the impression that as a major power, Beijing cannot allow itself to lose face to smaller countries and will instead force them to budge and make concessions.

Hopefully, the latest development signals a break with that mentality and suggests a more magnanimous approach towards the smaller countries. The well-thought out “Prosper-Thy-Neighbour” policies will thus help China to cement its position as a world power – a position it deserves. ■

Wang Xiangwei is the former editor-in-chief of the South China Morning Post. He is now based in Beijing as editorial adviser to the paper