Syria’s devastating war through the eyes of a Hong Kong nurse

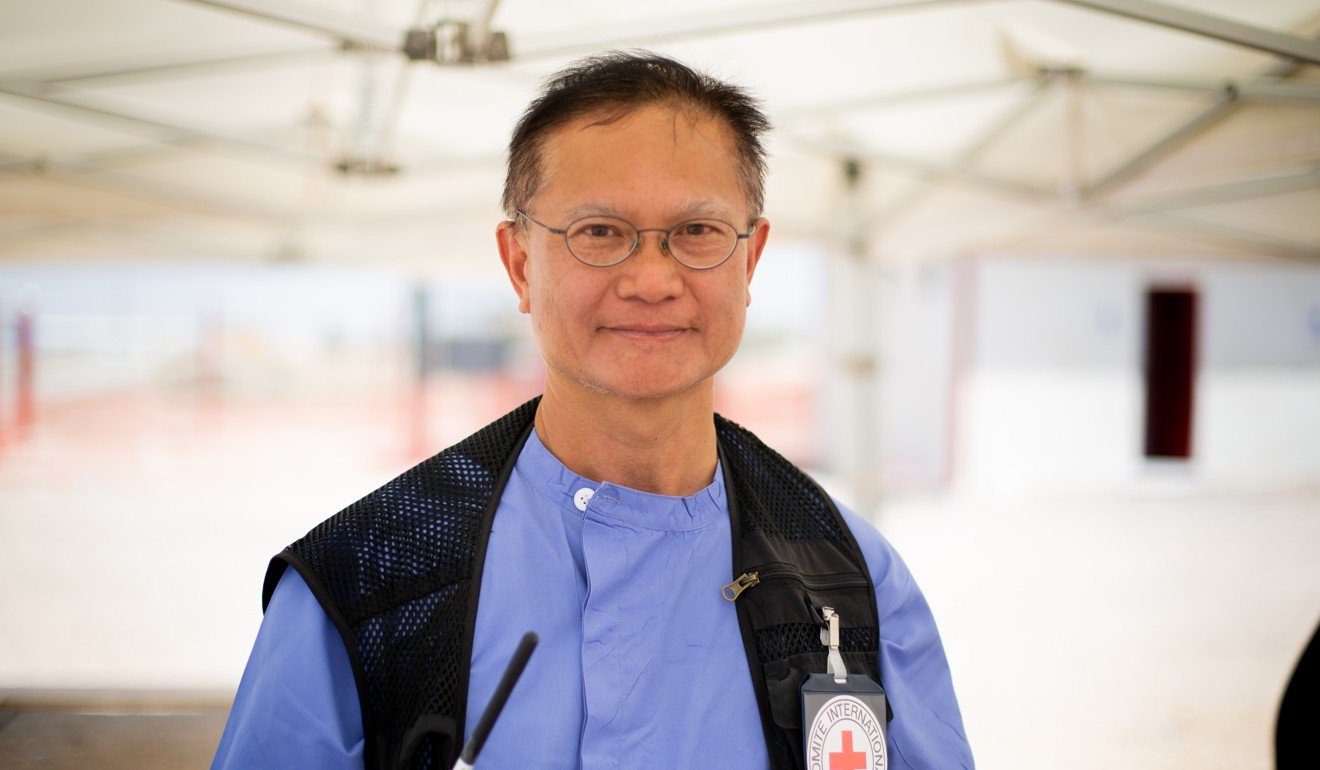

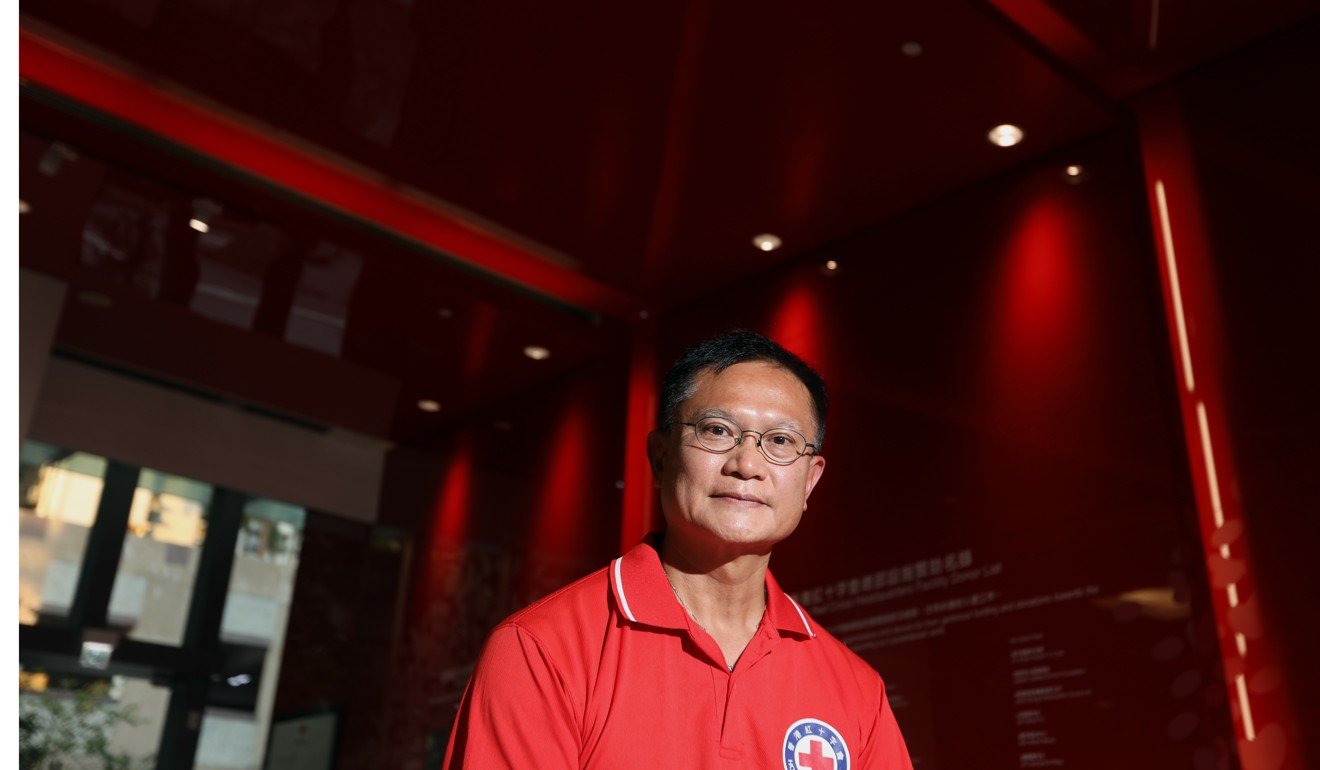

- Walter Leung Wai-yin has been on several missions for the Red Cross, but his latest to a hospital in the Al Hol camp has left him with vivid images of young, helpless victims of the war in Syria

Saad still has chubby, small hands like most children his age do. But his dark and penetrative eyes could belong to an adult. Though Saad is only 2 years old, the destruction caused by Syria’s deadly war has already left him with many invisible marks.

Saad had a fever and diarrhoea when he got to the hospital, a short walk on parched earth from the camp where he lives. Between his tent and the hospital, there are no trees and few places to escape the scorching sun.

Leung, a volunteer with the Hong Kong Red Cross, still recalls how afraid Saad was.

“Many children there are easily frightened. Many witnessed their family members being killed right in front of their eyes,” the nurse said. “Saad saw his father being shot … so he was easily frightened and scared by some noises.”

Due to intense fighting, thousands of Syrian families have fled their homes. While some were able to find refuge at friends’ and relatives’ homes, or sought asylum in other countries, many remain stranded at displaced persons shelters, camps or makeshift settlements.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, about 63,000 people arrived at the Al Hol camp since December. There are now about 74,000 people living in the camp, which was initially designed to hold 10,000. Around 90 per cent are women and children.

What next for Hong Kong’s extradition bill protesters?

“I felt that my experience and clinical capacity could contribute for this mission,” he said.

In mid-June he again packed his bag, filling it mostly with medical equipment, toys and balloons. “Many of these children experienced events that had quite a tremendous psychological impact. I take these things to make them a little happier,” he said.

Leung, who has used his holidays and non-paid leave to go on international missions, embarked on a long journey from Hong Kong to Beirut, Lebanon, then on to Syria’s capital Damascus. Eventually, he boarded a flight to Al Hasakah, a city not far from Al Hol.

“The most challenging thing was definitely the weather. It was more than 45 degrees during the day inside the [hospital] tents … and sometimes there were sandstorms. We were very prone to dehydration,” he said.

On the ground in Kashmir, feelings of loss, betrayal and helplessness as Srinagar remains in lockdown

Stationed at the hospitals triage office, every single medical case would go through Leung. He sent the most serious cases to doctors and handle the others himself.

“I would start the day talking to people who were waiting at the gate … and I would check the ones in the back, because they were often the sickest.”

Leung, who did not have access to the camp, said he used to see about 100 to 110 people a day. He recalled how many of the patients came in with war injuries, such has gunshot wounds or bomb injuries, while others, especially children, had fever, diarrhoea and anaemia. Psychological trauma, domestic related issues and pregnancies were also common.

He recalled the case of an eight-year-old in a wheelchair, whose mother came in saying a bullet had taken his life. “She meant that a bullet had gone through his abdomen to the spine, causing paralysis,” he said. The boy could not move his legs and his intestines had been cut.

He described another one-month old baby who came to the hospital from the annex with respiratory issues.

Every day they came to our hospital, mostly with war-related wounds, fragments in the hands and cartilage

“Actually the baby was dying, so I helped to take him the emergency room … finally the baby could be stabilised after two hours. Then, the doctors and nurses escorted this baby out to the hospital in Al Hasakah,” he said.

Leung said most of the patients with war injuries were refugees from the annex, who had only recently left conflict areas.

“Every day they came to our hospital, mostly with war-related wounds, fragments in the hands and cartilage,” the nurse said.

The field hospital in Al Hol camp, where Leung served, opened on May 30 as a joint initiative between the International Committee of the Red Cross, the Syrian Arab Red Crescent and the Norwegian Red Cross. By early July, it had treated more than 2,000 patients – 45 per cent of them being children, and a third of those under five years old.

“The International Committee of the Red Cross is particularly concerned about children living in the camps without their parents or habitual guardians, as well as other especially vulnerable persons,” a report from early last month said.

The humanitarian organisation has also raised concerns for the “huge” medical and surgical needs, and other daily challenges at the camp.

“We see many people who are injured, with their wounds bandaged, lying at the entrance of their tents, trying to stay out of the sun. Many children are carrying jerry cans of water to help their families – for some of them, the jerry cans are almost the same size as they are.”

Meanwhile, advocacy groups, such as Human Rights Watch, have highlighted the plight of more than 11,000 foreign women and children related to IS suspects who are being held “in appalling and sometimes deadly conditions”.

Down, not out Islamic State has US$300 million war chest to plot world terror

Human Rights Watch said in a report released at the end of July that they found on three visits to the section of Al Hol camp holding foreign women and children “overflowing latrines” and water “tanks containing worms”.

They “are indefinitely locked in a dust bowl inferno”, said Letta Tayler, senior terrorism and counterterrorism researcher at Human Rights Watch. “Governments should be doing what they can to protect their citizens, not abandon them to disease and death in a foreign desert.”

Many countries have been reticent, especially about taking adult parents, because of security fears and political matters.

The rights group in June interviewed 26 foreign women in the annex, originally from countries such as Canada, France and Australia.

From Sri Lanka to Indonesia, more mothers are becoming suicide bombers – and killing their children too

“I came to Syria because I was having problems at work and at home. It sounds so cliché. I was 20 when I left … If I have to go to prison I will. I just want to come home,” a woman from the Netherlands, who was married to an IS fighter, told Human Rights Watch.

Islamic State lost the last piece of its so-called caliphate in Syria in March. Its territory previously stretched from western Syria to eastern Iraq.

According to the UK-based monitoring group, Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, more than 371,000 people have been killed in Syria, including 112,600 civilians, since the civil war began in 2011. It is unclear how many of those casualties were specifically related to the fight against IS.

While millions of Syrian families and thousands of foreigners remain in camps similar to Al Hol, Leung has returned to Hong Kong after finishing his mission in mid-July.

He brought with him vivid images of those he treated as well as the sound of gunfire and warfare.

Married with three children of his own, Leung hopes his experience will set a positive example.

“Many people suffer with natural disasters and conflicts. They do not deserve this kind of suffering and we can provide some assistance. I hope to inspire some colleagues and friends.”

He said answering the call for help stems from his religious beliefs and his professional experience.

“I am very willing and ready for any mission.”