What do Chinese see in ‘Auntie’ Theresa May that Britons don’t?

Refusing to endorse the Belt and Road Initiative and securing hefty trade deals gives the British prime minister a much-needed political victory

Cosseted in the splendid meeting rooms, and being ushered in and out of VIP meetings, she will at least for once have been spared the constant questions of the press which she has to deal with back in Britain.

For China and Britain, some special relationships are more special than others

Once she arrives in 10 Downing Street she might sigh wistfully and look back at her three days in the People’s Republic and feel it was the lull in a storm – a moment of respite before the wind and rain started howling again.

At the very least, May’s visit to China went without mishap. She had a formidable task to start off with, so even achieving this was good.

Will French President Macron lead Europe down the New Silk Road?

That is a lot to achieve in such a small space of time. In one of the most tricky political terrains on the planet, she did well enough. While her visit might not have made waves, it did not create the wrong kinds of headline.

Politicking over and team in place, 2018 is when China’s Xi has to deliver on reforms

In her reluctance to get too close to the initiative she is in good company. French President Emmanuel Macron, who came to China a few weeks earlier, also did the same, as did the EU as a group at a belt and road summit last summer.

She, and they, refrained for a sound reason: she was being asked to support something that not even the Chinese really know much about. The initiative remains a vast ambitious but abstract idea, and to publicly support it would have been the equivalent of signing a blank cheque.

As the veteran business adviser in China Jim McGregor once pointed out, it is remarkable how often Chinese interlocutors ask for the impossible, and get promises to deliver it. May at least saw off this issue.

Chris Patten is wrong, Hong Kong will benefit from Brexit. Massively

On the positive side, she signed a reported £9 billion (US$12.8 billion) in deals, and she launched a review body between the Chinese and British government on investment and trade. The latter is of possibly the greatest strategic importance. It at least means that formally both sides can now sit down and think through what their relationship might look like once the EU has been removed from the equation.

Watch: Brexit won’t damage China-UK ties, Beijing says

They cannot, of course, talk explicitly of a free-trade agreement until Britain exits the EU. But they can in the abstract contemplate what such a thing might look like. That will at least get them geared up for going in earnest for a deal once they are in a position to do so.

Why a loss for Japanese farms is a win for Brexit Britain … and Hong Kong’s giant strawberry lovers

For all the rhetoric of a golden age, it is these who will have the biggest impact. It was good that May’s visit had recognition of this.

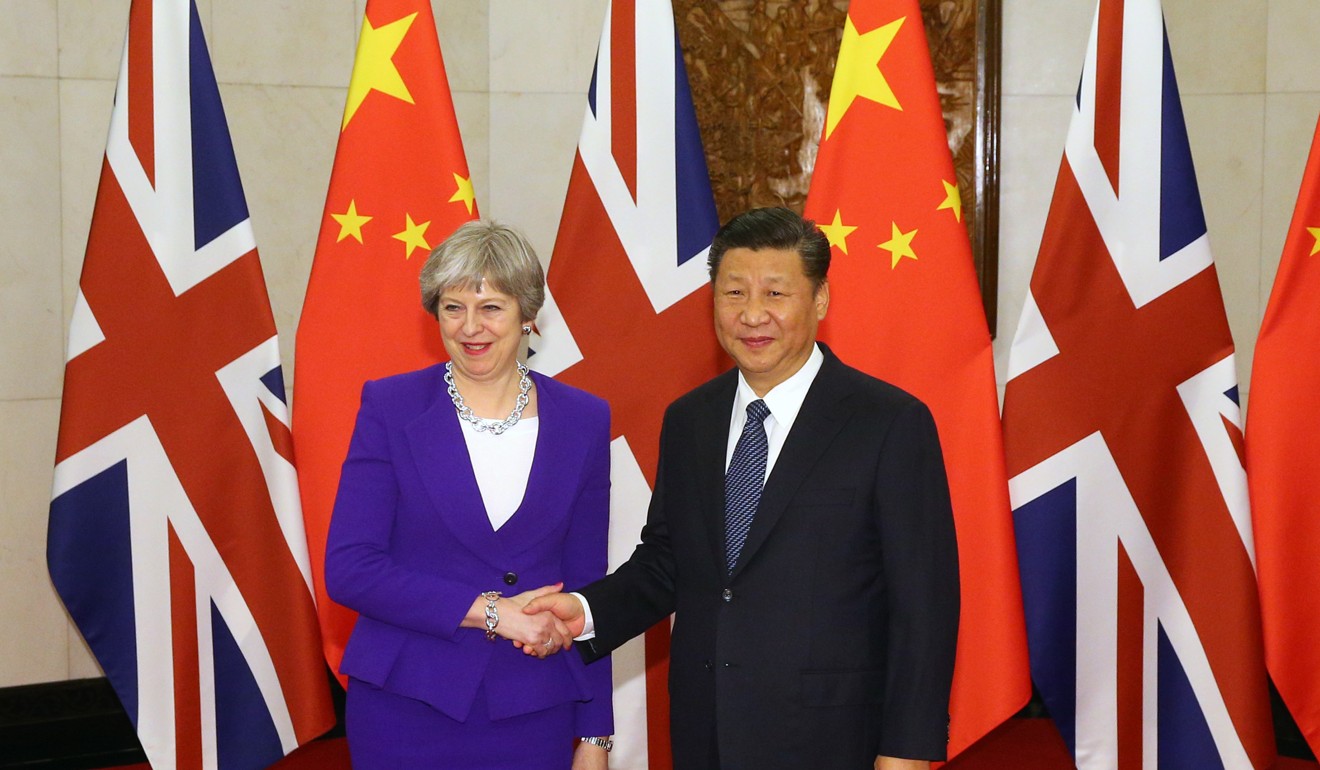

This was a trip that typified her style of leadership. May in Britain has been subjected to coruscating criticism for her subdued manner and her sometimes ponderous way of making decisions. Ironically, though, in China this lack of flashiness seen as her weakness back home seems to have endeared her to local people, with one interviewer telling her that her nickname was “Auntie May”.

This quality was reflected in the meeting – business-like, lacking the panache of Macron’s visit, or the inevitable histrionic drama when the Trump circus was in town late last year.

China may have the reins of globalisation, but it faces problems at home

But perhaps this approach is the one that works in Xi Jinping’s China – focus on practical things, not overpromising, being straightforward, and just getting on with things.

We don’t know who is ever going to really win in the battle to open the Chinese market and for once win in a deal with the Chinese – but my suspicion is that May’s approach might have more impact in the long term than that of others.

In that sense, even for a China novice, May may well have got China right.

Kerry Brown is director of the Lau China Institute, King’s College, London