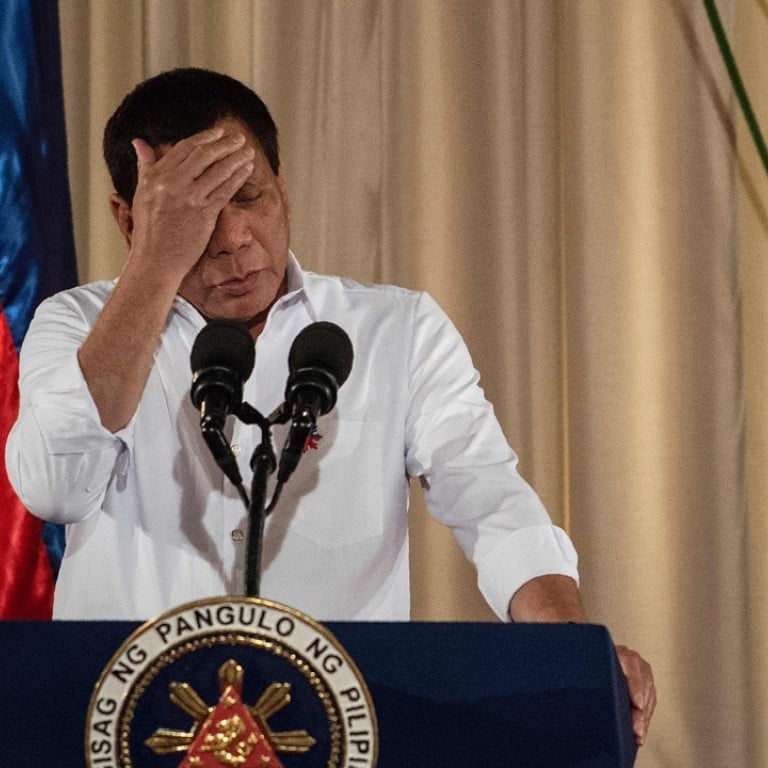

What now for Duterte’s China pivot as Marawi cements US importance for Philippines?

After being serially barked at, America is out of the doghouse, and

the strongman goes eerily silent

What a difference a few months make.

It was only October when Rodrigo Duterte announced his “separation” from treaty partner United States after months of an increasingly acrimonious marriage. “America has lost now,” the Philippine president pronounced at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing. “I’ve realigned myself in your ideological flow and maybe I will also go to Russia to talk to [President Vladimir] Putin and tell him that there are three of us against the world – China, Philippines and Russia. It’s the only way.”

There’s too much drug blood on America’s hands to lecture Duterte

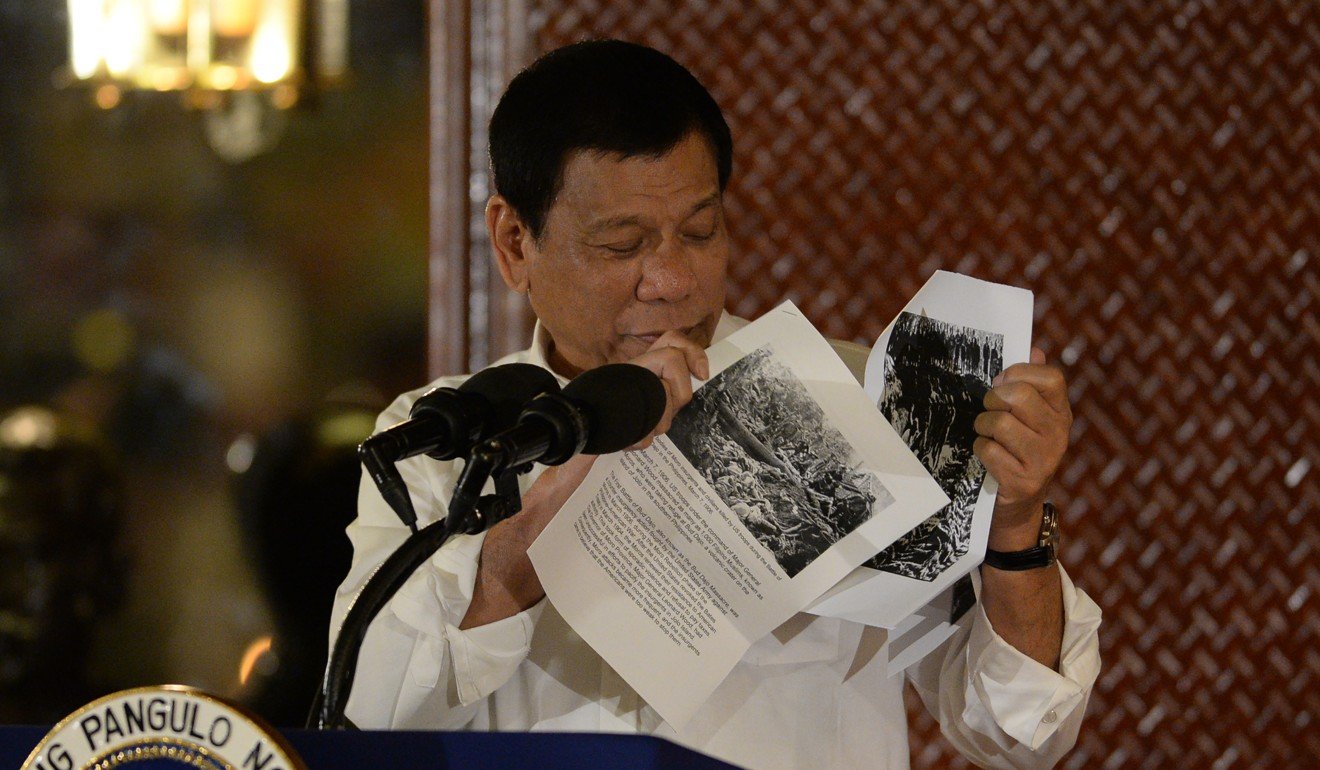

To rub it in, the US let it be known it was also providing fresh military hardware to the Philippine forces. Before Marawi imploded, Duterte has been repeatedly threatening to reduce purchases of US weapons in favour of Russian and Chinese arms. Before leaving for his Russia trip last month – which he cut short as a result of the Marawi crisis – he had announced that one of his top asks from Putin would be Russian arms for Mindanao. His Russia trip came just a week after his second trip to Beijing in less than a year, during which he secured a US$500 million loan to buy Chinese weapons.

Since taking power in June, the Philippine strongman has tried to build bridges with a rising China by setting aside a territorial dispute in the South China Sea and has sought to ease his country’s strategic dependence on the US. Rejecting American military help, including scaling down the number and scope of military exercises and patrols with the US, has been central to the self-styled socialist leader’s “independent” foreign policy.

Four reasons Duterte will have to change tune on China and U.S.

But according to Jay Batongbacal, director of the Philippines’ Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, much of it was mere grandstanding, with no real effort ever to structurally alter Manila’s relationship with Washington. “Marawi exposes Duterte’s rhetoric as well as his lack of understanding of how armed forces actually work – particularly the nature of linkages between the US and Philippine forces. One hopes he has learnt an important lesson here.”

Decades of working hand in hand means the two forces have developed a high level of synchronisation of tactics and procedures, or interoperability, in military jargon. The long association also translates into a comfort level and familiarity seldom seen between the two different forces.

“Almost all officers go to America to study military [affairs]…That’s why they have a rapport, I cannot deny that,” Duterte said this week in explanation of why the military had sought American help in Marawi – unbeknownst to him, as he claimed.

Not that China was holding its breath. “There was no illusion whatsoever here in China that Manila was going to make a choice between Beijing and Washington,” said Zha Daojiong, a professor at the School of International Studies in Peking University who advises various government agencies in Beijing. “His colourful language notwithstanding, Duterte only wanted his country’s relationship with the US to be less of an umbilical cord.”

The Philippines’ Rodrigo Duterte: saviour or madman?

Marawi, in fact, could have come as a mild relief to China. For several days before the declaration of martial law in Mindanao following the siege of Marawi, the story that dominated Philippine media was Duterte’s statement that Chinese President Xi Jinping ( 習近平 ) had warned him of war if Manila tried to drill for oil in the disputed areas. China could neither admit nor deny it – admitting it would enrage the Philippine public, and a denial would imply China was calling Duterte a liar. So even as demand for a public statement grew, all China could do was maintain silence, in the hope the storm would blow away. And blow away it did with Marawi.

As for Duterte’s pivot to China, Naval agrees with Batongbacal that there never actually was one – it was all hot air. And even if there was in fact a gradual realignment, China doesn’t expect America’s resurrection in the Philippine power structure to radically alter that direction. “The US would risk being lowered in the eyes of the Philippines and the wider region if somehow Washington were to demand that Manila from this point on stand up to Beijing as a payback for its role in Marawi,” said Peking University’s Zha. “That would be a different kind of hostage taking.” ■