As China bans national anthem ‘disrespect’, how will Hong Kong football fans react in match just before key Communist Party meeting?

With impeccable timing, the team’s next big game is shortly ahead of crucial five-yearly meeting

Hong Kong soccer doesn’t loom large in the annals of world history. It barely looms in the annals of Hong Kong soccer history.

But when accounts of the post-handover decades are written, and especially chapters dealing with the increasing anger and discontent among the post-97 generation (and Beijing’s heavy hand towards them), football will feature prominently.

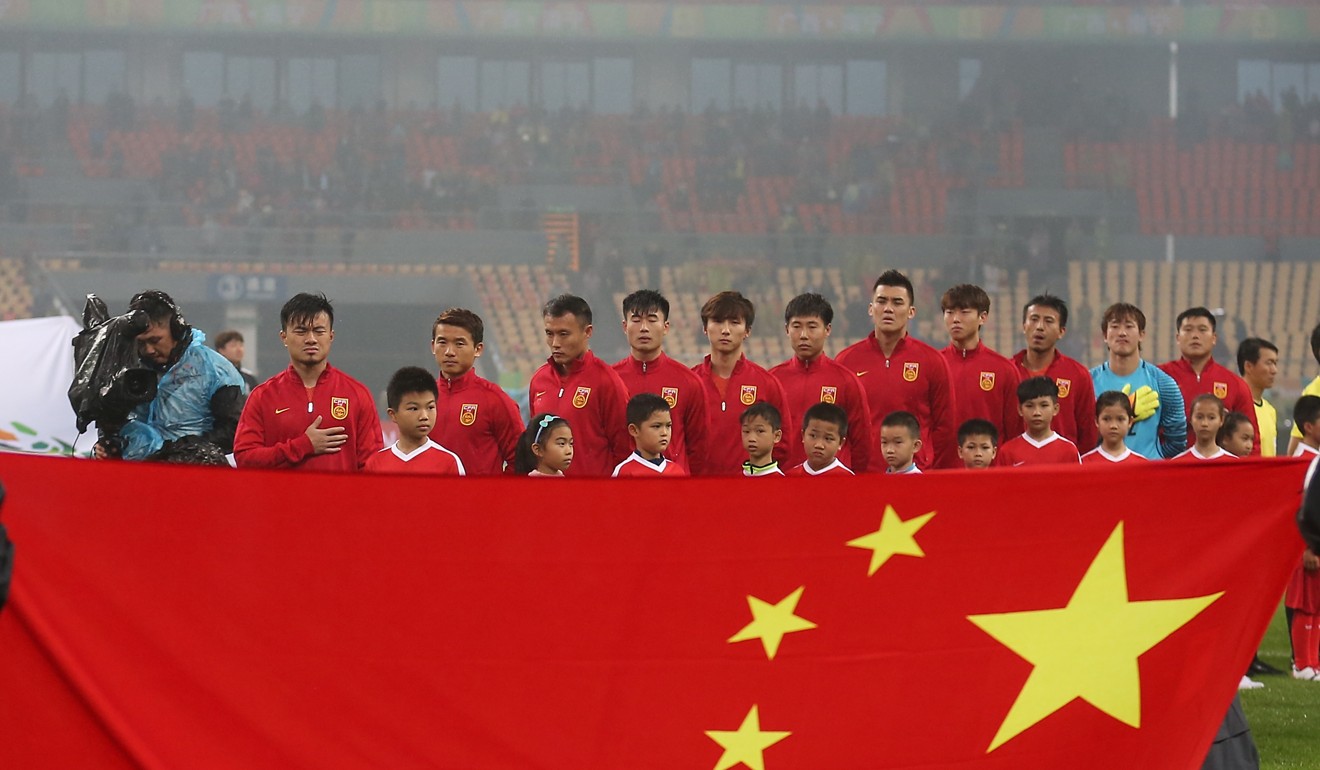

In the wake of the Occupy Central protests, anger moved to the football stands and the team’s World Cup qualification matches in 2015 became political events, with supporters booing the anthem before each game.

It attracted punishment from world governing body Fifa – and more importantly, it now seems clear, the ire of China’s power brokers.

Watch: How well do Hongkongers know their national anthem?

Supporters at Hong Kong Stadium for the Asia Cup Qualifier against Malaysia on October 10 will surely express their opinion of the anthem law quite clearly.

Another fine, or even a points deduction, seems likely to be heading to the Hong Kong Football Association’s headquarters. Perhaps an inconsequential concern given wider fears over free speech and repression, but still tough on the HKFA.

“It’s not for the HKFA to comment on mainland legislation or how it will be applied and relate to Hong Kong,” said its chief executive, Mark Sutcliffe.

“We will continue to play the anthem and it will be up to people to decide whether to respect it or not – we hope they do, otherwise we will potentially be fined by Fifa again.”

Watch: Why China’s national anthem is the saddest ever

It didn’t help that China and Hong Kong had been drawn in the same World Cup qualifying group – and Hong Kong’s next game was in China. I have never seen such a security presence at a sporting event as at that game in Shenzhen, though only a handful of Hong Kong fans were allowed across the border.

Could president Xi – a noted soccer fan – have been watching at home?

In the five years since he has been in charge he has crushed hopes that the country was becoming more liberal, and brooks no dissent.

You could imagine him getting straight on the big red phone after hearing Hongkongers – already in his bad books after Occupy – booing his anthem. “Sort it out,” he might have barked to underlings, with this law the result.

“Some Hong Kong fans do not like to be told what to do by the mainland,” said professor Brian Bridges, with some understatement.

Tobias Zuser, a local academic and football fan whose field is sporting culture in Hong Kong and China, and who co-hosts The Hong Kong Football Podcast, concurred.

“The big question will be how authorities would execute [punishment] against 6000 anonymous people. Who booed and who did not?

“I don’t think the law would be successful in muting political dissent at games – and it might just trigger fans to think of ‘creative’ responses.”

Hong Kong v Malaysia suddenly got a lot more interesting.