Wary US Supreme Court could extend Donald Trump’s immunity bid past November election

- Chief Justice John Roberts criticises appeals court ruling against former US president Donald Trump

- US Supreme Court could order more review, dooming trial before the November 5 US election

The US Supreme Court suggested it might drag out Donald Trump’s claim of immunity from prosecution, an outcome that could doom any chance of a pre-election trial on charges of trying to stay in power illegally.

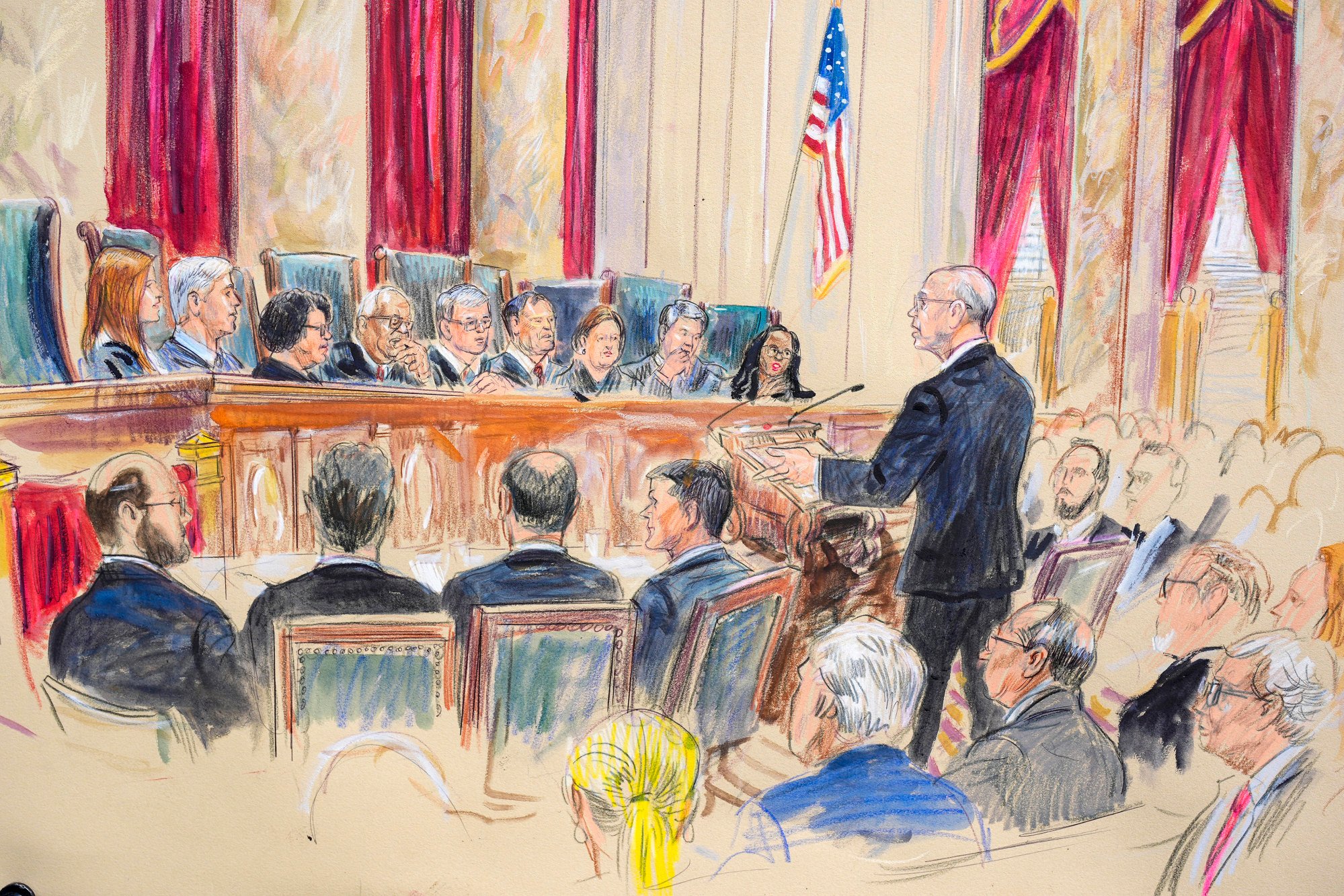

Hearing arguments Thursday in Washington, the justices expressed scepticism toward the former US president’s sweeping arguments for immunity for his efforts to overturn Joe Biden’s election victory.

But a pivotal member, Chief Justice John Roberts, said he disagreed with part of an appeals court opinion letting the trial go forward, and he discussed returning the case to the lower courts for a closer look at the allegations against Trump.

“The Court of Appeals did not get into a focused consideration of what acts we’re talking about or what documents we’re talking about,” Roberts said.

Another key justice, Brett Kavanaugh, said he was worried about the long-term effect of leaving presidents vulnerable to prosecution for their official acts.

He said he was concerned that “it’s going to cycle back and be used against the current president or the next president – and the next president and the next president after that”.

Arizona indicts Trump allies Giuliani, Meadows, 16 others in 2020 election scheme

Special Counsel Jack Smith has only a narrow window to put Trump in front of a Washington jury before voters go to the polls on November 5.

The judge overseeing the case has said she will allow three months to prepare for a trial that could last two to three months. Polls indicate a conviction of Trump could undercut the presumptive Republican nominee’s election chances.

The schedule matters all the more because of the broad expectation that, should Trump reclaim the White House in January, he would take the extraordinary step of ordering the Justice Department to drop the prosecution.

The 2024 election went unmentioned over the course of the two-hour 40-minute argument, though Justice Amy Coney Barrett at one point acknowledged that Smith “has expressed some concern for speed and wanting to move forward”.

The case is one of four prosecutions hanging over Trump, including one already proceeding in New York state court over hush money payments to a porn star.

Trump has also claimed presidential immunity in those cases, even though many of the allegations involve alleged conduct when he was a private citizen.

The Supreme Court has never said whether former presidents have immunity from prosecution. The court ruled in 1982 that, with regard to civil suits by private parties, presidents have complete immunity for actions taken within the “outer perimeter” of their official duties.

Trump contends that former presidents have so-called absolute immunity for official acts they took. His lawyers say everything he did in the run-up to the January 6 riot – including allegedly promoting false claims of election fraud, pressuring the Justice Department to conduct sham investigations, pushing then Vice-President Mike Pence to undercut certification of Biden’s victory and inciting a crowd to storm the Capitol – was part of his job as president.

The court’s liberal justices were skeptical. “If there’s no threat of criminal prosecution, what prevents the president from just doing whatever he wants?” Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson asked.

Justice Elena Kagan said the country’s founders knew how to provide immunity in the Constitution, and they didn’t do so for the president.

“Not so surprising, they were reacting against a monarch who claimed to be above the law,” she said. “Wasn’t the whole point that the president was not a monarch, and the president was not supposed to be above the law?”

The liberals got some support from Barrett, who questioned the assertion by Trump’s lawyers that former presidents can’t be prosecuted unless they are first impeached by the US House and convicted by the US Senate.

“There are many other people who are subject to impeachment, including the nine sitting on this bench,” she told Trump’s lawyer, John Sauer. “And I don’t think anyone has ever suggested that impeachment would have to be the gateway to criminal prosecution for any of the many other officers subject to impeachment.”

Echoing arguments Trump has made outside the courtroom, Sauer told the justices that “without presidential immunity from criminal prosecution, there can be no presidency as we know it.”

Smith contends that all presidents until Trump have understood that after they left office they were subject to prosecution for official acts.

“His novel theory would immunise former presidents from criminal liability for bribery, treason, sedition, murder, and, here, conspiring to use fraud to overturn the results of an election and perpetuate himself in power,” said Michael Dreeben, the lawyer in Smith’s office who argued the case.