Explainer | Not all bun and games: a look at the history and controversies behind Hong Kong’s Cheung Chau Bun Festival

- Traditional event returns after three-year hiatus, but in a much watered-down iteration

- The Post explores other past challenges for the festival and how it has evolved through the decades

Much like previous versions, the highlight of this year’s festival will be a so-called bun-scrambling competition set to run late Friday night into the early hours of Saturday morning.

But this comeback has not been smooth sailing, with hiccups centred on the iconic bun towers. The Post unpacks the saga and more related to the 2023 edition of the festival on the outlying island.

What is Hong Kong’s bun festival on Cheung Chau all about?

1. What is the latest challenge?

The festival traditionally features three towering bamboo columns lined with auspicious steamed buns stamped with the Chinese characters for “peace”.

But this year, organiser Hong Kong Cheung Chau Bun Festival Committee announced the structures would be reduced from 45 feet (13.7 metres) to just about 15 feet, and three banners representing the usual size of the towers had been put up as the backdrop instead.

The committee explained the exclusive contractor that had been in charge of building the towers for generations had quit due to labour shortages, difficulty in securing materials and being unable to find a suitable venue to do the work. The contractor who had inherited the business refused to take the job even when it was offered HK$130,000, which is about HK$40,000 more than the usual amount.

The reduced size also means fewer buns. Kwok Kam Kee, the iconic Cheung Chau bakery that has long been partnering with another store to produce buns for the towers each year, pulled out this time to concentrate on making the delicacies for visitors and residents instead.

The amount of buns needed for the smaller structures this year has been halved to just about 10,000, which will all be produced by Hong Lan Bakery.

2. What are the bun towers for?

The three usual giant bun towers, along with many smaller ones, are erected as part of a wider, weeklong festival with Taoist origins celebrating the Pak Tai deity.

The entire island of Cheung Chau goes vegetarian during the festival. Even the local branch of fast-food chain McDonald’s joins by taking meat off the menu to be replaced by a mushroom burger.

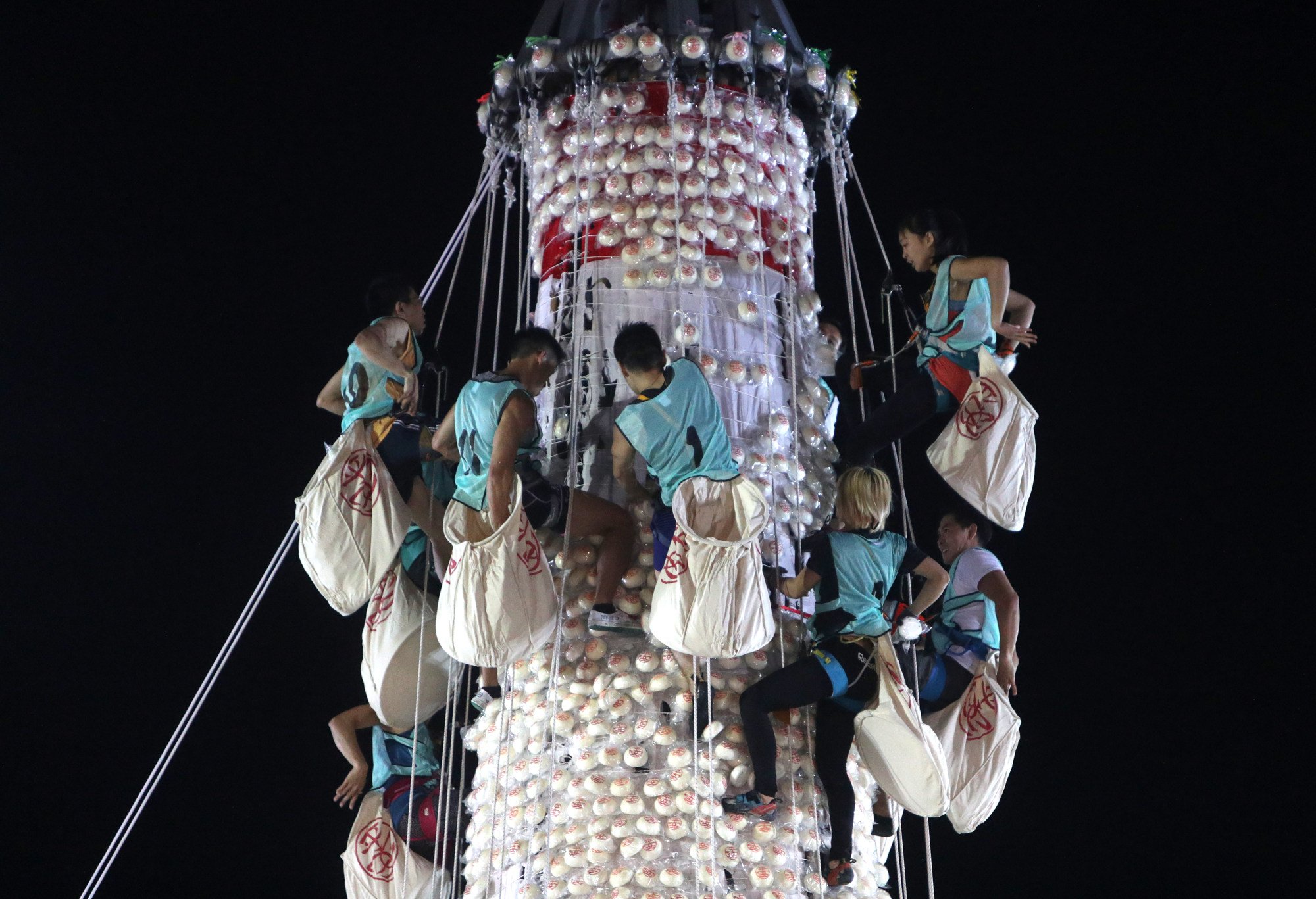

Other events include the burning of paper effigies, a children’s float parade known as Piu Sik, and a bun-scrambling competition, for which a separate bun tower made of steel instead of bamboo is built.

On the final day of the festival, the buns are passed out into the community as they are believed to contain blessings and good luck.

3. What are the origins of the Bun Festival?

Also known as the Cheung Chau Da Jiu Festival, details about the origins of the event vary but most stories say that the island was devastated by a plague in the 18th or 19th century and villagers carried out rituals such as offering buns to deities to end the outbreak.

Some versions of the story say an image of Pak Tai, or “God of the North”, was paraded through the streets to drive away evil spirits as villagers dressed up as various deities followed along. Others claim the island was attacked by pirates, and the rituals were conducted to appease the spirits of the people who had died.

4. What other past dramas have plagued the event?

Historically, the bun-scrambling competition was a mass, male-only activity, with young Cheung Chau men free-climbing bamboo bun towers to snatch as many buns as possible. It was believed the higher the buns were placed, the better the fortune.

Amid public trauma, authorities announced the following year the bun-scrambling race would be cancelled.

It would not return for another 26 years.

Cheung Chau bun festival race yields repeat champions

In 2005, the Hong Kong government relaunched the race as a tourist attraction, but with stringent safety measures, including a requirement that the bun tower for climbing should be made of steel, and that only 12 finalists would take part after several rounds of preliminaries.

Participants were to go through training, wear safety belts, and carry a backpack for their snatched buns.

For the first time, the competition would also be open to women.

5. Has the revamped event ever been cancelled?

The relaunched bun festival has been dropped or cut short four times since 2005.

In 2015, the bun-scrambling portion of the festival was cancelled due to bad weather.

From 2020 to 2022, the festival was suspended three years in a row as Hong Kong shut itself off from the world and enforced tough social-distancing rules amid the pandemic.

6. How does the bun competition work?

Annually, some 200 people sign up for the first round of the bun scrambling competition, which occurred on April 16 this year, but only 12 finalists get to take part in the flagship event at midnight on the day of the race.

Participants will scale the steel tower to snatch plastic buns – each of which carries a score according to their placement – in an attempt to win several titles.

Men’s and women’s champions, first and second runners-up are determined through overall points, while the winner of “Full Pockets of Lucky Buns” is the person who bags the most number of individual buns.

A “King of Kings” or “Queen of Queens” title, launched in 2016, is also given to champions who have won three times.

A team relay competition, with five per group, also took place on May 14.

7. Who are the finalists in this year’s bun-scrambling competition?

Nine men and three women make up the dozen finalists this year.

All eyes will be on Cheung Chau native and firefighter Jason Kwok Ka-ming, who has been in every final competition that took place since 2005, except for 2011.

He has won the men’s champion title nine times in total and was crowned the first “King of Kings” in 2019.

Bun-believable: Hong Kong festival’s bamboo towers to be two-thirds shorter

He easily breezed into this year’s final by snatching first place in a qualifier last month, climbing to the top of a bunless tower in 42.96 seconds – beating fellow firefighter Kidman Yip Kin-man in second place by more than five seconds.

Yip has also been a familiar face in many finals, and was champion in 2016.

The other male candidates are three-time finalist Wong Chi-kit, Kwok Chi-wai, Lai Wai-chun, Chung Yuk-chuen, Tam Kin-hung, Liu Chi-lun and Chan Kwok-kin.

On the women’s side, 2019 winner ad local ice-climbing athlete Janet Kung Tsz-shan won the preliminary competition with a time of 49.66 seconds, while five-time champion Angel Wong Ka-yan took second place and Chau Yuen-sin came in third.