National security law: Hong Kong residents, protesters flock to Taiwan, but is it the right destination?

- Growing number of Hongkongers have set their sights on the island in recent years. Many arrive lawfully but others have tried illegal means to get there

- Following city’s social unrest and imposition of security law, immigration consultants report a sharp rise in inquiries from residents about moving elsewhere

Today marks the 100th day since the imposition of the national security law on Hong Kong on June 30. In the first of a series, the Post looks at how it has affected the flow of Hong Kong people leaving the city for Taiwan. You can read part two here.

Jack Chan* finally started university in Taipei last month, more than half a year after fleeing Hong Kong for Taiwan.

Then an email arrived.

“It said that I had been admitted to a university,” he said. “Many other Hong Kong protesters, especially the young ones, have also been admitted to universities here.”

It was a dream come true for Chan, one of an estimated 200 activists said to have gone to Taiwan since last year’s unrest, though it was unclear how many still remained there.

“The Taiwan government has done all it can to help us,” added Chan, who has applied for a resident’s certificate which will allow him to work legally.

Taiwan has become a destination for a growing number of Hongkongers in recent years. Many of them, like Chan, arrive legally and hope to stay, but some have tried to arrive illegally too.

Others have also contemplated leaving Hong Kong, with immigration consultants reporting a sharp rise in inquiries from Hongkongers asking about moving to Taiwan and elsewhere.

Britain, Australia and Canada are among countries that have responded to the law by saying they will welcome Hongkongers who want to leave. From January next year, about 2.9 million Hongkongers holding British National (Overseas) passports can apply to settle in Britain.

In July, Taipei set up the Taiwan-Hong Kong Service and Exchange Office to help those wishing to settle there, while making clear it did not encourage illegal immigrants.

The following month, 12 Hongkongers were captured at sea by mainland Chinese authorities while fleeing to Taiwan by speedboat to escape prosecution over their roles in the city’s protests.

Last month, Taiwan’s semi-official Central News Agency revealed that five other Hong Kong activists had been detained in July while trying to sneak into the island by boat, raising doubts about the Taiwanese government’s supposedly tolerant approach towards those fleeing there.

Figures from Taiwan’s immigration authorities show that 4,148 Hongkongers were granted residency and 1,090 obtained permanent residency in 2018. Those numbers rose to 5,858 and 1,474 respectively last year.

From January to August this year, 4,596 Hongkongers were granted residency and 1,057 obtained PR.

It is not known how many of the more recent departures were protesters.

From activist to illegal worker

Chan flew to Taiwan on a tourist visa after police turned up at his home in Hong Kong sometime after midnight looking for him.

He was abroad at the time and immediately decided to go to Taiwan instead of returning home. With the help of friends, he settled down with other Hongkongers in similar straits.

He said the Taiwan-Hong Kong Service and Exchange Office offered him substantial help but declined to elaborate.

“Other protesters have also been assisted by the Mainland Affairs Council,” he said, referring to the body that handles Taiwan’s relations with mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau. “There haven’t been any obstacles in applying to stay in Taiwan.”

His first few months were tough, as he was not fluent in Mandarin and could not find jobs legally. He eventually adjusted to his new life and applied to join a Taipei university, setting him on a path to a more stable future.

“There were no obstacles at all. I just applied online, submitted my Hong Kong education certificates and filled out some information,” said Chan, who described himself as working class.

He declined to talk about his alleged offence in Hong Kong, except to say that he supported the use of violence as he found peaceful protests to be futile.

Chan said that in Taiwan, he told people he was from Hong Kong without elaborating, but if anyone asked, he would not deny his identity.

Like him, many other Hong Kong protesters worked illegally because of visa restrictions. He said Taiwan’s minimum wage of NT$158 (HK$42) per hour, higher than Hong Kong’s HK$37.50, was enough to make ends meet.

Chan was pleased with the way things had turned out for him, but advised activists in Hong Kong not to attempt going to Taiwan illegally.

“If you can enter Taiwan legally, come here. If you are thinking of coming here illegally by boat, do not do it,” he said.

“I cried at the airport for about 30 minutes. I sat next to the window and … I saw the sky of Hong Kong,” she said. “I couldn’t stop crying.”

But she decided to leave Hong Kong because she felt her hometown had become too messy, after Beijing imposed the national security law.

“Hong Kong is not safe,” she said, noting that several of her friends had been arrested while taking part in protests.

She chose Taiwan over Britain because she was born after the 1997 handover and does not have a BN(O) passport.

Taiwan, US or somewhere else?

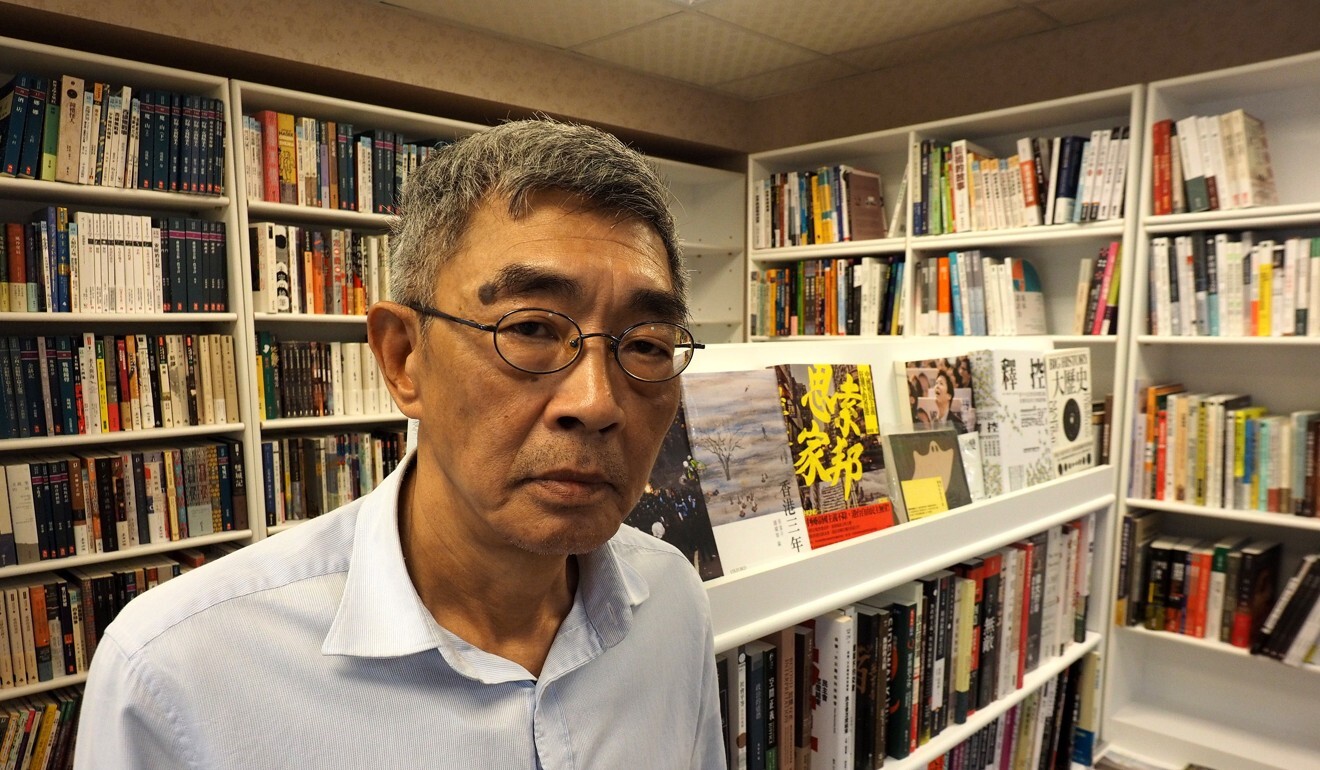

He and four other associates from the bookshop, which sold books critical of the Chinese Communist Party leadership, disappeared under mysterious circumstances in Hong Kong, the mainland and Thailand.

After Lam managed to return to Hong Kong, he said he was kidnapped by Chinese agents while crossing the border.

He fled to Taiwan last year, raised nearly NT$6 million through crowdfunding and reopened his bookstore in Taipei in April this year. A banner proclaiming the protest slogan “Liberate Hong Kong; revolution of our times” sits proudly on top of his desk.

“I am living a much better life here than in Hong Kong. How can I not get used to living here?” said the 63-year-old, who lives in the bookstore, with his bed right behind his desk. “I will never return to Hong Kong. The city has lost its future.”

He said he knew of Hongkongers who remained jobless for almost a year after arriving in Taiwan, attributing their plight to rules on hiring non-locals as well as the struggling economy.

“Many people in Taiwan are supportive of Hongkongers, but there are still people who are not,” Lam said. “The Taiwanese government also needs to listen to public views. It cannot help Hongkongers in a very high-profile way.”

He said the Taiwan government had already done all it could for Hongkongers, and urged the United States, which has been critical of the national security law, to make it easier for Hongkongers to settle in the country.

Last month, Lam told a visiting US delegation to consider letting Hong Kong activists settle in the country. The delegation was led by Keith Krach, the US undersecretary of state for economic growth, energy and the environment.

“Hong Kong protesters can see Taiwan as a ‘transfer station’, and then have the option to go somewhere else, like to the US,” he told the Post.

But not everyone views Taiwan as a first-choice destination. A 32-year-old Hong Kong engineer planning to leave because of the political climate said he preferred to go to Britain.

“If I move to Taiwan, I still will not be able to get away from Beijing’s influence,” he said.

Between a rock and a hard place

Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen’s open support for Hong Kong’s anti-government protests led to her landslide election victory in January, but she has since been criticised by political rivals for not doing enough for Hongkongers.

The government has been “passive and evasive” in responding to the needs of Hongkongers, said Cheng Chao-Hsin, deputy chairman of the Culture and Communications Committee of the Kuomintang, which was once Taiwan’s dominant political party.

“It just feels like after they drifted to us, we felt embarrassed to send them back, so that we just hid them somewhere,” he said. “Without proper laws to guarantee their rights, Hongkongers can only live here with an illegal identity.”

Bei Ling, a Chinese dissident based in Taiwan who has helped those fleeing the mainland, pointed out that Taiwan had no refugee laws spelling out how asylum seekers should be treated.

“You need broad support from different political parties to pass the law. There is still a long way to go,” he said.

In 2018, Chinese activists Liu Xinglian and Yan Kefen arrived at Taipei’s Taoyuan airport seeking asylum. But they were stuck at the airport for four months because there was no law for the handling of refugees, and the United Nations’ refugee agency did not operate there.

The pair were eventually allowed to enter Taiwan and stayed several months at a shelter arranged by Bei, the dissident said, before leaving for Canada which agreed to take them.

“Hong Kong people are very lucky already,” Bei said. “You just can’t demand that any country in the world should encourage people to arrive illegally and settle.”

Chiu E-ling, executive director of Amnesty International’s Taiwan office, said the human rights organisation and other civic groups had been campaigning for refugee laws, fearing that the treatment of arriving Hongkongers could change if Tsai’s Democratic Progressive Party lost power in future.

She said the Mainland Affairs Council normally gave asylum seekers in Taiwan a monthly allowance of NT$20,000.

Draft refugee bills have failed to pass in Taiwan’s legislature for 15 years, as the issue is considered sensitive amid the tense cross-strait relations with the mainland. A key question is whether mainland Chinese can be considered refugees in Taiwan, as that would challenge Beijing’s one-China policy.

Professor Milton Yeh Ming-deh who teaches mainland China studies at Chinese Culture University in Taipei, expected that Taiwan would continue to attract Hongkongers to study and work legally as long as fear of the national security law loomed large in the city.

Hong Kong is not an independent war zone but part of the territory of China, so people fleeing from there are never defined as refugees

But he warned it would be unwise to introduce provocative refugee legislation amid escalating tensions in the Taiwan Strait, as that would give Beijing an excuse to increase military activity or threaten retaliation.

“I don’t see an immediate possibility of Beijing attacking Taiwan. But a potential new cold war or China’s further suppression of dissent will benefit no one,” he said.

He also questioned Taiwan’s capacity to take in a large number of refugees, including Tibetans and Vietnamese, if it had an official open-door policy.

He felt the current low-key approach was in everybody’s best interests.

Former Taiwan defence minister Andrew Yang Nien-dzu said a refugee law in Taiwan would never be a solution to help Hongkongers.

“Hong Kong is not an independent war zone but part of the territory of China, so people fleeing from there are never defined as refugees,” Yang said.

He suggested that Tsai’s government streamline existing mechanisms or amend the immigration law to offer humanitarian aid to Hong Kong arrivals, but felt any high-profile help to fugitives entering Taiwan illegally would only escalate cross-strait tensions.

“Taiwan, China and the US have to come up with the best wisdom in restraining provocation and to avoid a miscalculation,” he said.

Additional reporting by Laura Westbrook

*Names changed at the request of the interviewees