Hong Kong children expose their identities, thoughts and flesh to millions of strangers on popular iPhone app Tik Tok, Post finds

Parents and social workers express alarm as hundreds of underage youngsters upload information identifying themselves on social media platform used by millions around the world

Hundreds of Hong Kong children, some as young as nine, are exposing their identities, innermost thoughts and even flesh to millions of strangers on the world’s most popular iPhone app, an investigation by the Post has found.

Tik Tok, a fast-growing social media platform on which users make videos set to music, has taken the city by storm.

While users must be aged 16 or above, at least 100 local primary school pupils – identified through videos showing them in uniform or their real names or phone numbers – are active on the app, having posted between 10 and 500 clips each. More than 40 users are between the ages of 10 and 12, according to their bios and confirmed by the Post.

Video app Douyin brings Chinese out of their shells, beats YouTube, Facebook in download charts

Disturbing scenes were found in suggestive videos simulating sexual acts and self-harm, uploaded to draw the attention of other users.

The Post also identified suspicious adults using the platform to stalk and court teenage girls.

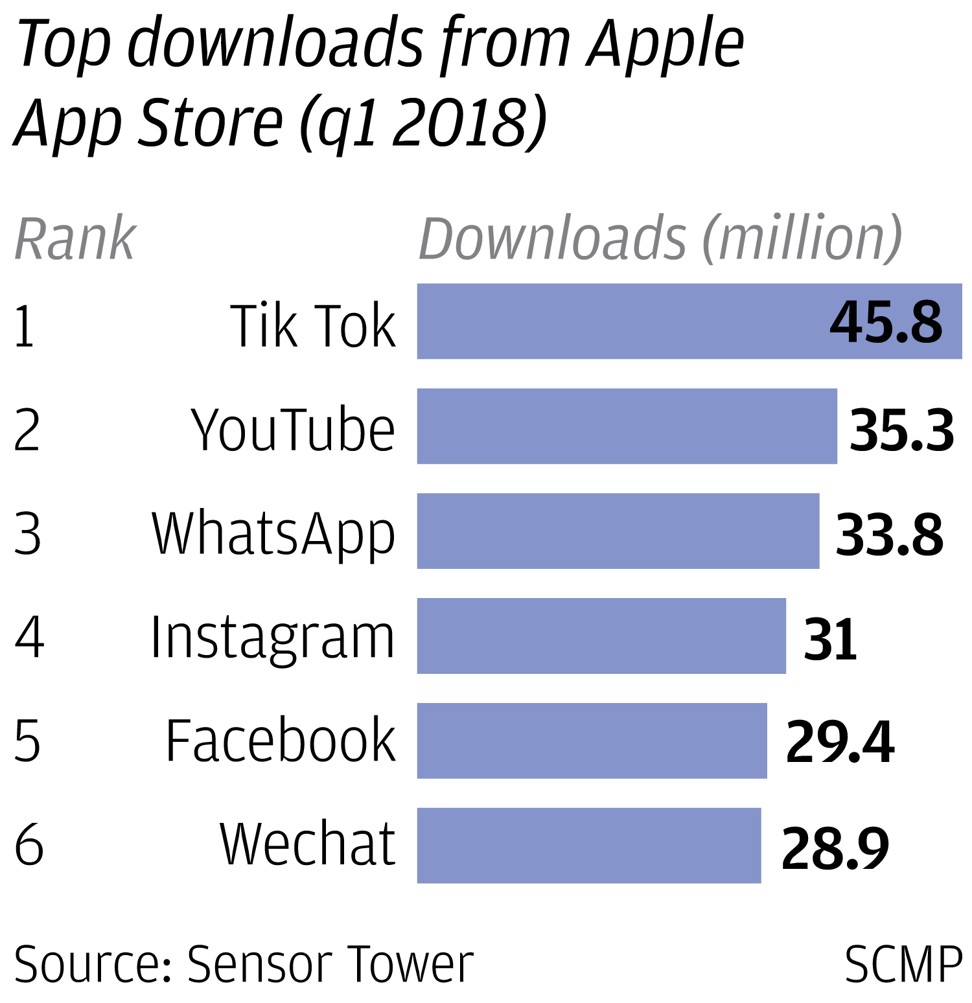

The app was developed by the Chinese firm Bytedance, which offers a version on the mainland called Douyin. It has found staggering success. In the first quarter of this year, Tik Tok was the most downloaded iPhone app worldwide, totalling 45.8 million and surpassing Facebook, YouTube and Instagram, according to the American research company Sensor Tower.

‘I risked my life, please like!’ Mobile app Tik Tok has Hong Kong children craving acceptance – and some are going to dangerous extremes

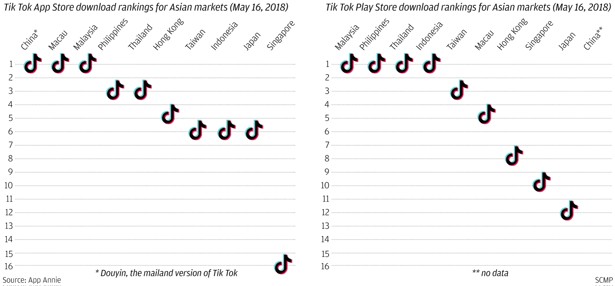

It is the most popular photo and video app in Hong Kong, Japan and much of Southeast Asia including Indonesia and the Philippines, and ranks first among iPhone apps in Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand and Vietnam, according to data company App Annie.

“Tik Tok has changed me a lot,” a sixth-grade primary schoolboy in Hong Kong told the Post through private messages on the app. He said about 20 of his classmates used it.

The boy revealed that his nine-year-old sister also had a Tik Tok account, and begged the Post to identify him in its report to boost his popularity among the app’s tens of millions of users.

He said he felt “like a celebrity when he was spotted in the street after posting a video”.

Both he and four other primary school pupils said they spent about an hour on Tik Tok every day.

What social media platforms run Hong Kong and what are the implications?

At least three videos from Hong Kong children – one of primary school age and two at the secondary level – had suggestive content. All three used as background music the song Buttons by the band The Pussycat Dolls, and the children unbuttoned their shirts, slipping them off their shoulders. One of the children simulated having sex.

In a fourth video, a child about to enter a secondary school played with a box cutter while complaining about the pressure she faced to study hard.

Some adults have followed and commented on the children’s videos, including a man claiming to be a Hongkonger who follows the accounts of more than 1,000 young girls.

In comments on the app he asks the children to be his girlfriends and seeks their mobile numbers. Under one sexually explicit video, he left the comment: “I like it”, in Cantonese.

Douyin has stoked safety concerns on the mainland. In one case, a 10-year-old girl was harassed by a man she met using the app.

Authorities there have warned Bytedance to better filter its content and handle public complaints in a more timely manner.

Social workers and parents in Hong Kong are increasingly alarmed, with some calling for a crackdown on Bytedance.

Wong Yung-shan, a registered social worker with Caritas Primary School Guidance Service, noticed more local Hong Kong children were using Tik Tok.

“Children may not be aware of what kind of personal information they have disclosed while posting on social media,” Wong said.

“If [criminals] know where the students study, and what they look like, plus they have other personal information, the students can be identified easily, and might be harassed.”

Hong Kong privacy watchdog demands answers from Facebook on data security

Annie Cheung Yim-shuen, a spokeswoman for the concern group Parents United of Hong Kong, asked why authorities had not cracked down on Bytedance.

“Just look at the platform. It’s full of children obviously under 16 years old. Why doesn’t the platform take any action?” she asked.

Cheung, who has an 11-year-old daughter, called on the operator to review the accounts and content closely.

It’s full of children obviously under 16 years old. Why doesn’t the platform take any action?

“They shouldn’t let such accounts exist, even if they are internet celebrities,” she said. “Without legislation, there’s no way to sue the platform operators for breaching the rules and regulations.

“Children always look up to adults and want to be famous,” she added. “They may not know what is sexy, or they know, but don’t know they are not supposed to post such things.”

In Tik Tok’s English-only terms of service, the app is described as not directed at children under 16, and if underage users are found to hold accounts without parental or legal consent, they will be deleted.

It also reminds users not to post content that would constitute or encourage a criminal offence, dangerous activities or self-harm.

Unlike other social media platforms, no easy option exists for Tik Tok users to delete their accounts. One must make a request and provide detailed personal information.

In addition, one can only block a specific account manually. The videos posted online can either be “private to only myself” or “public to everyone”.

Privacy Commissioner for Personal Data Stephen Wong Kai-yi declined to comment on Tik Tok, but said his office had issued a leaflet showing social media operators how they should collect and use personal data involving children.

Wong said operators “should ensure children are well informed of their rights” and offer them an easy way online to “completely remove personal data”.

Information technology sector lawmaker Charles Mok said a lack of regulation in Hong Kong meant it would take “something really [serious] to happen” before the government stepped in.

“It needs more media coverage as well as advice from parents and schools,” Mok added.

Barrister Choy Ki, convenor of the Progressive Lawyers Group, said Hong Kong’s outdated privacy law and failure to protect children made them vulnerable on social media. He suggested referring to the European Union’s new general data protection regulation, which requires data controllers to verify parental consent.

Responding to the Post’s questions on children’s use, a spokesman for Tik Tok said it had put in place protective measures such as privacy settings, keyword filters and a system to remove inappropriate content.

“Tik Tok is committed to protecting the safety of all our users,” he said in a statement.