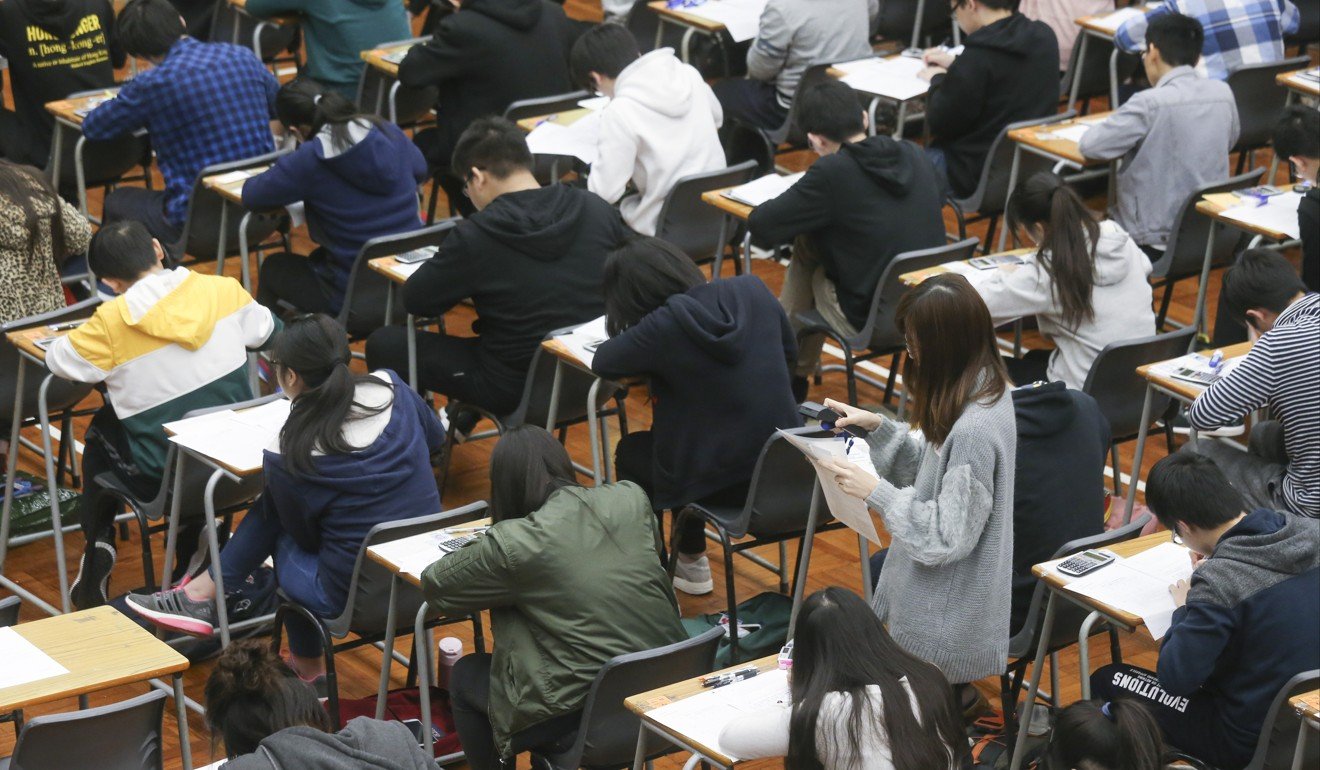

Inside Asia’s pressure-cooker exam system, which region has it the worst?

Mainland China’s gaokao, Hong Kong’s DSE and South Korea’s suneung … top-performing Asian regions all feature tough college entrance tests and a highly competitive admissions environment

Nearly 10 million young people are heaving a sigh of relief as China’s standardised college entrance test, the gaokao, comes to a close, but the pressure-cooker exam culture it creates is not only a Chinese phenomenon. It exists across other Asian countries and regions, sometimes at the expense of students’ well-being.

The gruelling nine-hour test, known as the gaokao, began on Thursday and, in most places in China, ends on Saturday.

Countries in the Asia-Pacific region outperformed most others in the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Survey and Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results from November 2016, accounting for eight of the top 11 countries.

The winners, including Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea and Japan, all feature tough university entrance exams in highly competitive and stressful environments.

Here is a look at some of Asia’s top-performing regions.

MAINLAND CHINA

The gaokao can make or break a young person’s future, and the pressure surrounding the test is extreme.

Stories have included accounts of students using IV drips to aid concentration while studying, and of teenage girls taking contraceptive pills to delay their periods until after the test. Parents have booked nearby hotel rooms for their children to rest between tests, prayed outside exam rooms and blocked roads surrounding exam halls to lessen traffic noise.

According to Sohu.com, only 2 per cent of test takers in 2016 were admitted by the top 38 schools in China, and 0.05 per cent were admitted to Tsinghua and Peking University, considered the Oxford and Cambridge of China. With 9.4 million people having taken the exam, this means that only 188,000 made it to the top 38, and just 4,700 to Tsinghua or Peking.

A huge discrepancy between institutions means students are trying to reach a few prestigious universities, adding to the competitiveness and the rising pressure to study, said Xiong Bingqi, deputy director of the Beijing-based 21st Century Education Research Institute.

“People try to get into good schools as a way to secure better development down the line,” he said, adding that the situation was similar in Japan.

Many criticise the system for stifling creativity.

“China’s way of evaluating students’ performance is relatively one-dimensional” when compared with neighbouring Asian countries, Xiong said. “They spend a lot of time in school and their responsibility for rote learning is greater.”

China has vowed to create a new system by 2020 that includes more diverse standards for university admission and lessens regional inequality.

HONG KONG

Hong Kong has also been criticised for its exam-oriented culture and high family expectations, starting from a young age.

Beginning at age nine, pupils sit the Territory-wide System Assessment to gauge English, Chinese and mathematics ability. The tests are thought to rank schools, creating top-down pressure on students, although the government denies it.

In 2015, tens of thousands of parents signed a Facebook petition asking that the exams to be cancelled, leading some schools to boycott the test and forcing the government to admit problems with the system.

“It is understandable there might be a lot of worries as Hong Kong children prepare for tests so young,” said Assistant Professor Eva Chen, a cognitive social development specialist at Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, citing similarities with children in Singapore and South Korea.

“They start interviewing for kindergartens, or even day care, from a very early age. From there all the way to university there are always interviews or exams they have to face.”

A global report by HSBC in 2017 found that 88 per cent of Hong Kong parents were paying or had paid for private tuition, below 93 per cent of mainland Chinese parents but above the global average of 63 per cent.

Almost half of them – the highest global percentage – said they would forfeit personal time and hobbies to help their child succeed, and 37 per cent had reduced or completely stopped leisure activities or holidays.

“With the [Diploma of Secondary Education] being seen as the final hurdle before university, I’m sure the pressure, combined with the exhaustion they have, can be very concerning,” Chen said. “As an educator, and from the perspective of parents, I would worry.”

Hong Kong University admitted 10,062 undergraduates for the 2016-17 academic year. It said it could not provide the number of applicants, but said several years before that “the average number of applications over the past few years is about 50,000”. If that figure is still current, it means about one in five applicants gained admission last year.

SINGAPORE

After six years of school, Singaporean children take the national Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE). Scores are sent to secondary schools, who choose pupils based on merit.

Children are streamed into one of three curriculums that match their abilities, based on PSLE results. Ranked from highest to lowest, they are express, normal (academic) or normal (technical), according to the education ministry. Those in the top group take university entrance exams after secondary education, and those in the lowest tier typically go into vocational work.

“Human beings are inherently different in abilities, potential, talents and interests,” said Jason Tan Eng Thye, an associate professor at the National Institute of Education in Singapore, explaining the need for the streaming system. “So you need differentiation to better meet the needs of such a diverse group of learners.”

“[But] Parents and students know you are going to have explicitly unequal educational outcomes for different groups of students”, and therefore they attach superiority to certain schools known for exam results and university transition rates, he said.

“You then have a certain group of parents who will try to summon whatever financial resources or social networks they have to give their children that competitive edge,” Tan said.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) established the PISA test, which evaluates education systems worldwide by testing 15-year-olds in key subjects. In 2014, an OECD survey found the average 15-year-old Singaporean was spending roughly nine hours a week on homework, nearly double the global average.

Though the OECD hailed Singapore in 2015 for having “the world’s best education system”, the government has sought to reduce the stress and anxiety brought on by unhealthy competition and a culture of private tutoring amid concerns about diminished behavioural and social skills.

It vowed to end, by 2021, the scoring system that displays pupils’ performances relative to their peers. In 2012, it stopped listing the top-scoring students in all national exams.

Competition for top universities remains fierce.

The National University of Singapore, ranked the island’s top university in the Times Higher Education’s World Rankings 2018, received about 28,000 undergraduate applications this year. According to a school official, only 7,000 of those students will get in.

SOUTH KOREA

The annual college scholastic ability tests in South Korea, known as suneung, determines which university pupils will get into. Offices stay open late to keep roads clear for students, and aeroplane take-offs and landings are halted during some exams.

According to a January 2017 report by the Korea Institute of Child Care and Education, the country’s study culture starts young: More than 83 per cent of five-year-olds attend after-school education programmes, or hagwon, and many continue to do so throughout their school years.

In 2016, following the PISA results, the BBC reported on three Welsh teenagers who travelled to South Korea to experience life as a South Korean secondary school pupil. They found South Koreans studied up to 16 hours a day in preparation for exams.

Suicide rates in South Korea are the second highest globally and the highest among the OECD’s 34 industrialised nations. Suicide is the leading cause of death among South Korean teens and young people, with much of the blame placed on societal and family pressures relating to education. It is the No 1 cause of death for those aged 10 to 30, OECD data in 2015 showed.

Unlike China, however, Japan and South Korea “still allocate time to nurture students in their extracurricular activities”, such as exercise, Xiong said.

“In China, some schools sacrifice students’ time exercising in order to spend more time studying.”

JAPAN

Japan is in the process of changing its standardised college entrance exam, known as the “Centre Test”. Its goal is that by 2020, the exam should reward critical thinking and deviate from pure rote learning.

Cram schools, called juku, are common. At the end of high school, pupils take one exam that will determine their future, and the period of preparation is known as juken jigoku, or “examination hell”. Many universities also have their own admission exams.

Japanese companies pay close attention to prospective employees’ backgrounds, making competition for prestigious universities high. Students who do not make it into their preferred choice will often wait a year to retake the centre test. In 2011, about 442,000 students took the exam for the first time, of which 110,000 retook it, according to the National Centre for University Entrance Examinations.

In 2014, a study by Japanese neuropsychiatrists found about 58 per cent of those retaking the test suffered from depression, as they dealt with a loss of identity, sense of failure and anxiety over sitting for it again.

“The pressure is huge in Korea and Japan,” said Professor Rui Yang, associate dean of the faculty of education at the University of Hong Kong. “But once a society develops economically, the pressure is lessened.”

This is the same across Asia, he said. As countries develop economically and educationally, people can afford to send their children abroad to avoid exams like the gaokao, and society pays more attention to children’s all-round development.

But for those in the lower classes, he said, “getting into a good school and a good job is the only way to move up. For those families, the competition is really tough”.

That was certainly the case in China, he said, adding: “That is the only way for them to get rid of a hard life.”