Behind the urgent drive to unite China’s giant panda habitats in one huge national park

Proposed conservation area would connect dozens of protection zones and forestry parks against a looming threat to the country’s national icon

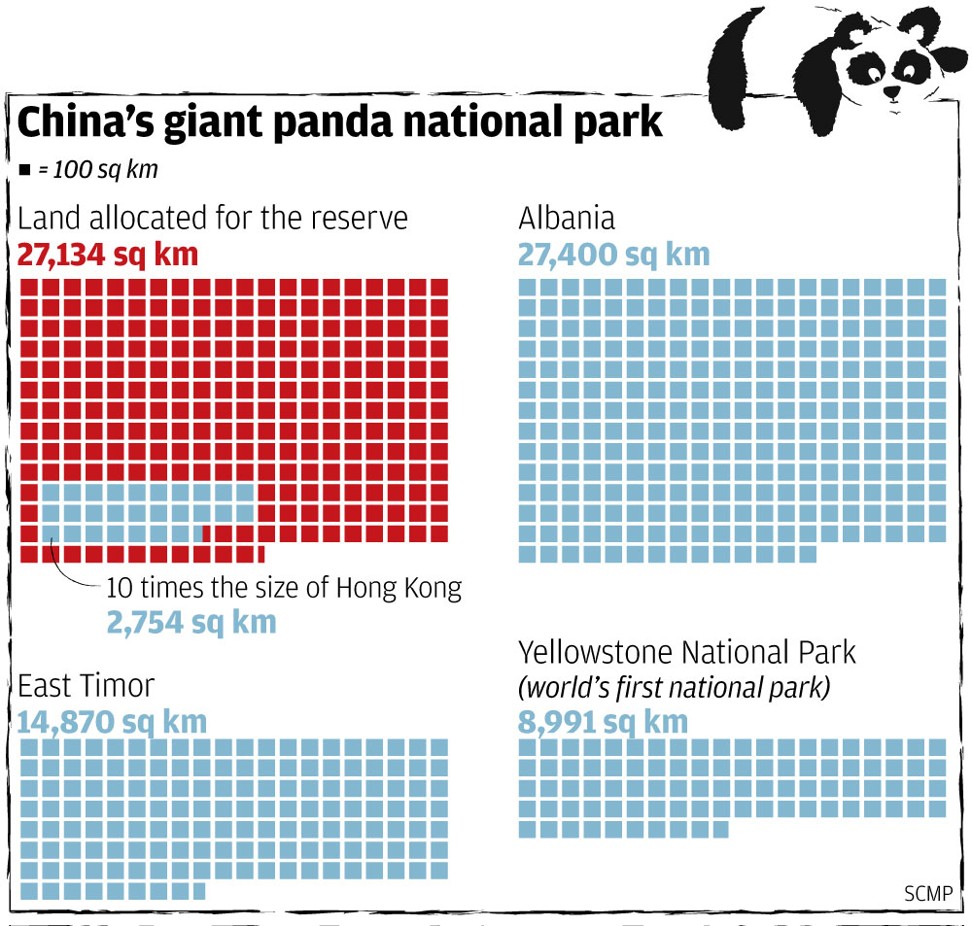

When it’s finished it will be 10 times the size of Hong Kong, stretch across three provinces and force the relocation of tens of thousands of people.

It will link dozens of isolated habitats, cover thousands of varieties of flora and fauna and be a first for China.

The Giant Panda National Park will also have one overarching mission when it opens in 2020 – to fend off a new extinction threat to the country’s animal icon.

For a while there the giant panda seemed to be out of the woods. National surveys put the wild population at 1,864 in 2014, far fewer than 40 years ago but up slightly from a decade earlier.

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) concluded the species was rebounding and last year lowered its status from “endangered” to “vulnerable”.

The IUCN said the unexpected uptick was cause for celebration, saying the hard work of replanting bamboo forests and controlling poaching was paying off.

But the State Forestry Administration continues to insist that it is still too early to lower the threat level to the species.

There may be more giant pandas but they’re clinging to each other in smaller groups, dramatically shrinking the gene pool, specialists say.

Fan Zhiyong, a senior supervisor at WWF’s Beijing office, said roughly 1,600 giant pandas were living in 18 separate population groups more than 10 years ago.

Since then the number of population groups has almost doubled to 33, 22 of which have fewer than 30 of the animals and 18 groups that have no more than 10, according to Sichuan authorities.

“A small population means there’s a high possibility for pandas to inbreed and mate with [other giant pandas with] similar genes,” Fan said. “It’s very bad for the panda’s reproduction and will lift the risk of their extinction.”

He said the segregation of population groups was worsening and it was necessary to create the national park to integrate the isolated habitats.

A document about the proposed park on the Sichuan government’s website said that in the past one to two decades, wild giant pandas had retreated to more remote areas and their population become more fragmented, due to more intense human activity, natural disasters and climate change.

The new park will sprawl across 27,134 sq km, three-quarters of which is in Sichuan province and the rest in Shaanxi and Gansu, linking more than 80 protection zones and forestry parks, according to state-run Xinhua. More than 8,000 animal and plant species are found in the conservation areas, with giant pandas the region’s “flagship species”.

Yang Biao, from the Chengdu office of US-based Conservation International, said a national park also had to be large enough to protect a complete ecological system.

Yang said biological corridors would be built between the separate panda reserves to allow populations to combine.

“But the effort of letting them ... communicate naturally will take time,” he said.

Roughly 20 plans for such corridors have been proposed since 1988 but not one has yet come to fruition, official media report.

There has also been no announcement of which government agency will oversee the park but its supporters say it will streamline administration for giant panda conservation in one set of hands.

Luo Peng, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Chengdu Institute of Biology, said the national park would bring together 29 natural protection zones, 14 scenic zones, 13 forest parks, four geographic parks and two natural heritage sites – each one managed a different arm of government.

“Some are managed by county governments, while some are run by provincial governments,” said Luo, a member of the panel that drafted the park’s blueprint.

But there are major hurdles to overcome. Xinhua reported that at least 170,000 people in Sichuan alone would have to be relocated to make way for the park.

Yang said that under IUCN rules indigenous residents would have to be allowed to stay in the area.

Authorities have yet to assess who will stay and who will go.

Luo said there was also resistance from communities expected to take an economic hit from the creation of the giant panda protection zone.

“Factories in the national park that violate regulations [for national parks] will be closed,” he said.

But Fan from the WWF said a national park could lead to solutions from a “broader and higher” perspective.