Chinese robotic hand picks up a top prize at RoboCup 2017

Two-fingered design gives a masterclass in dexterity and navigation to see off all comers at international contest in Japan

When it comes to designing robots with dextrous digits, you’ve got to hand it to the Chinese, especially now that a local university has picked up a major prize at an international design competition.

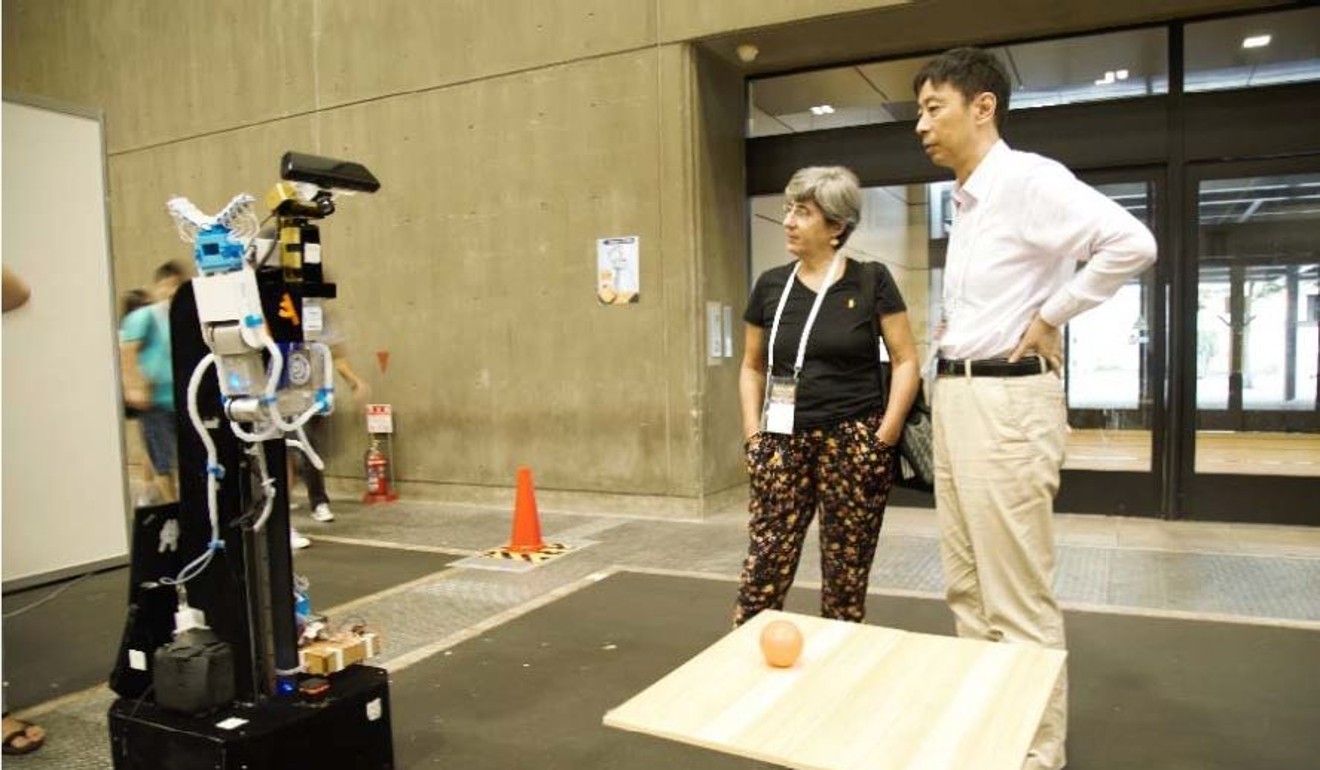

Developed by the WrightEagle team from the University of Science and Technology of China in Hefei, capital of southeastern China’s Anhui province, “Kejia” took on all comers over the weekend to be named “Best in Manipulation” at this year’s RoboCup in Nagoya, Japan.

According to a statement posted on the university’s website on Sunday, Kejia outperformed its rivals in a series of tasks designed to test manual dexterity. These included picking up and putting down random objects, such as an orange, computer mouse, shampoo bottle and milk carton.

As well as being a test of the robots’ handling skills, the manipulation contest was held in an “open world” environment, meaning the machines had to demonstrate their navigation skills, the organisers said

This meant that Kejia had to be aware of its start position, calculate a route to the table on which the objects to be picked up were placed, and interact with “unpredictable elements” along the way.

Because of the number of variables, the manipulation category is regarded as one of the most challenging and prestigious in the whole of RoboCup.

According to its developers, Kejia’s success can be attributed to two key factors: its advanced manual dexterity and rapid processing speed.

The machine is “better than any other mechanical hand in existence today,” they said, adding that while other robots spent a large amount of time scanning subjects for “comprehensible data on shape and size to guide the gripping action”, Kejia was able to “reach out after its first glance”.

It can do this because the design of the hand, which comprises a mechanical skeleton and soft, gas-filled “muscles”, allows it to fit closely around any object regardless of its geometry or size, the team said.

While Kejia is unlikely to win any beauty contests – it is effectively a claw at the end of an arm on wheels – the technology it encapsulates is expected to be in “enormous demand” in everything from manufacturing and logistics to home services, agriculture, disaster relief and national defence, the university statement said.

Kejia’s design team was led by professor Chen Xiaoping, who has been working on the development of soft-body robotics technology for the past six years. Earlier this year, Chen and his team unveiled “Jiajia”, one of the most lifelike humanoids ever built.

While Kejia lacks Jiajia’s “good looks and sweet voice”, the new design would make a very “handy” housekeeper, the university said.

China has invested heavily in soft-body robots in recent years because of their perceived value in key sectors such as defence and even space warfare.

Their designs incorporate elastic materials and are generally gearless so that they can accurately mimic the natural movement of an animal or human body. This ease of motion and manual dexterity means soft-body robots can accomplish tasks, such as maintaining spacecraft or retrieving sensitive components from satellite, that would be too delicate or sophisticated for machines with a rigid structure.

Ding Xilun, a space robotics scientist at the Robotics Institute at Beihang University in Beijing, said that competition in the field of soft-body robots is heating up.

“The race is on to develop the first human-like robotic hand,” he said. “It will not only have bones and muscles, but also skin and nerves to feel the subject’s temperature, texture and weight. Its movement will be guided by artificial intelligence algorithms.”

Despite Kejia’s success in Japan, Ding said it had not yet been tested against the world’s best.

“The win in Nagoya was somewhat lucky,” he said. “Some of the best teams we know of, including one from Germany and one from the US, did not participate in the competition.”

He said also that Kejia’s simple structure – with only two fingers – would prevent it from doing some tasks that a human would consider simple, such as threading a needle.

“[However] China definitely won’t sit idle and see the technology fall into the hands of others, because it offers a grip on power.”