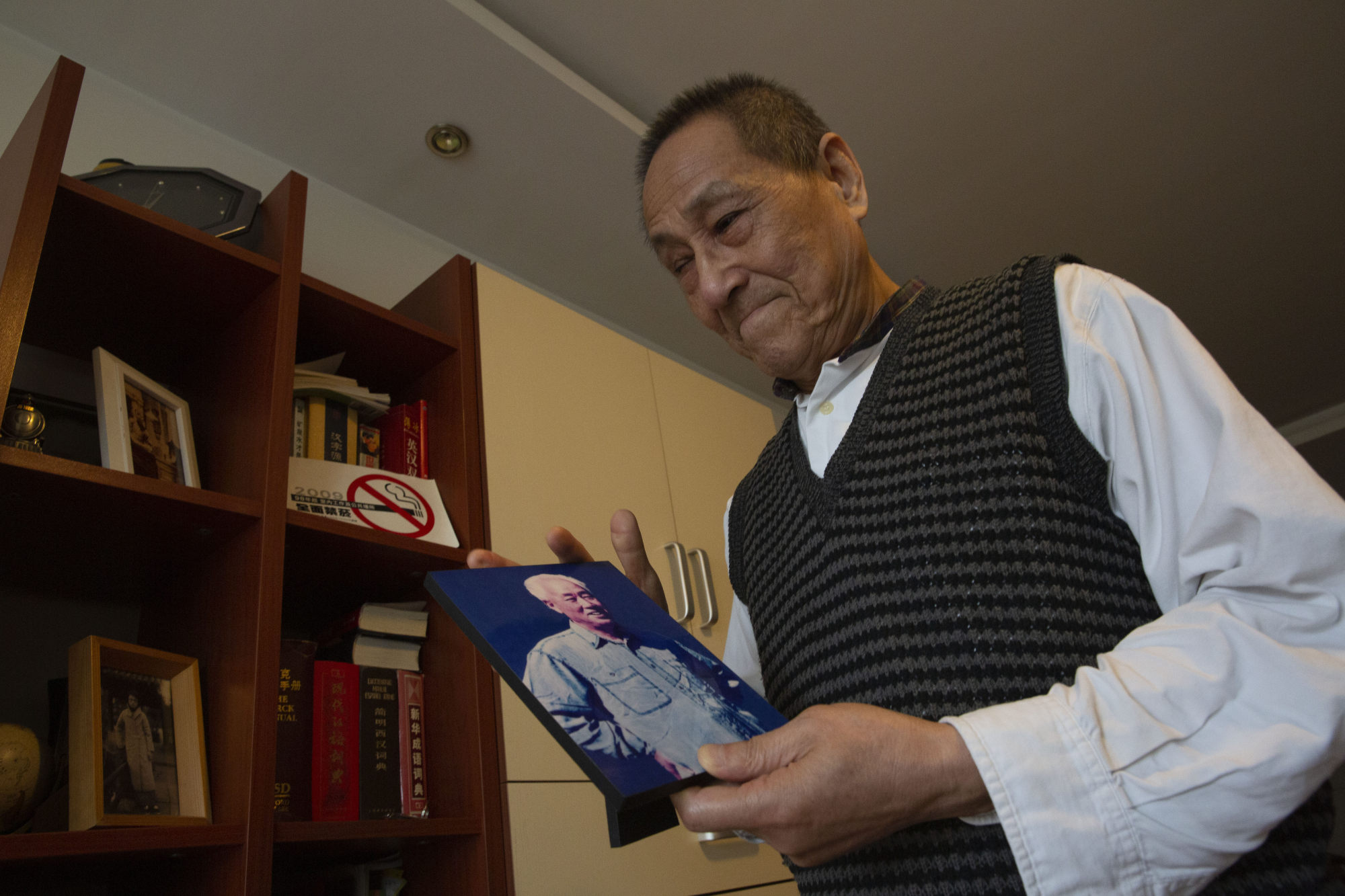

Bao Tong, senior Chinese official turned pro-democracy activist, dies at 90

- He was the top aide to leader Zhao Ziyang and played a key role in pushing political reform in the 1980s

- Brought down in a purge, Bao spent seven years in jail and the rest of his life under de facto house arrest

“From life to death and from compassion to kindness, he never ceased advocating from this sense of morality that we all ought to do our best,” his son Bao Pu said on Thursday from Beijing. “He demonstrated this through his life journey … so his final days were happy.”

Bao Tong died in hospice care in the Chinese capital on Wednesday morning, days after his 90th birthday on November 5.

As director of a top research office on the party’s political reform, Bao also headed a team that drafted documents for the 13th national congress in 1987.

That report, delivered by Zhao at the five-yearly conclave and still available to the Chinese public, famously called for a separation of the party and the state, which would limit the party’s involvement in the everyday operation of the government.

Bao, along with Zhao, was brought down in a purge of student sympathisers in the party. Zhao spent the rest of his life under house arrest until he died in 2005, while his top aide Bao was expelled from the party and spent seven years in jail for leaking state secrets.

Bao – who had been one of the 175 members of the party’s leadership body, the Central Committee – was the most senior official to be jailed in the 1989 purge.

His death is being widely mourned, especially among Chinese pro-democracy activists.

“This is an extremely rare and precious spirit in Chinese politics and it calls for respect and remembrance. He was a pioneer, pushing for China’s political reform within the party,” he said.

“After 1989, many with similar beliefs were persecuted and eliminated. There was no real reformist left but Bao persisted – his ideological perseverance is his biggest political legacy.”

Since his release in 1996, Bao has been under de facto house arrest in Beijing, with limited freedom to travel within the city and see people.

“Ever since his release from prison, this policy of isolating him from society has not let up,” his son Bao Pu said. “It’s been consistently implemented for at least 25 years, with people guarding his apartment at the doorstep on three shifts around the clock, to prevent him from having any contact with the outside world.”

But despite the restrictions imposed on him for nearly three decades, Bao Tong has remained a vocal pro-democracy activist and critic of the party.

“He was always known as a free thinker within the party but after his formal break from the party, his mind and his thoughts were totally free,” Bao Pu said.

Inspired by Charter 77 – a document written by Czech pro-democracy activists in 1977 – the Chinese manifesto called for freedom of speech and assembly, judicial independence and an elected government determined by universal suffrage.

Beijing responded with a heavy-handed crackdown, jailing Liu for 11 years on subversion charges in 2009. Liu was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize the following year, and he died of cancer in 2017 while still serving the jail sentence.

Aspirations for a more liberal society are still alive [in China]. He’s not the first and he’s certainly not the last

A funeral will be held for Bao on November 15 in Beijing, with just 30 people allowed to attend, according to his son. Bao Tong’s wife, Jiang Zongcao, died three months ago, also at the age of 90. They are survived by their son and a daughter, Bao Jian.

“I think he has lived a life filled with purpose, particularly his relationship with the party – that the party changed but his purpose, deeds and beliefs remained principled,” Bao Pu said.

Bao Tong’s extensive writing about his public life has been published in a collection of essays and other books. His son said he also had an unpublished memoir written by his father and recordings based on their conversations over the years.

“Aspirations for a more liberal society are still alive [in China]. He’s not the first and he’s certainly not the last,” Bao Pu said. “He didn’t see himself as a beacon of hope, but somehow through his writing, he inspired those aspirations.”

Rana Mitter, a professor of the history and politics of modern China at the University of Oxford, said Bao Tong had shown that it was possible to be both central to the narrative of the Chinese revolution and a principled advocate of a more liberal and transparent political sphere that welcomed debate.

“He lived in the spirit of thinkers such as the great May Fourth thinker Cai Yuanpei – that the most important thing was honest and open political discussion, not simply sticking to an ideological position,” Mitter said.