Being immortal: inside Xi Jinping’s power play to reach the same status as Mao Zedong

General secretary tipped for recognition with eponymous ideological ‘banner term’, following in footsteps of Mao and Deng

Communist Party chief Xi Jinping could see his name enshrined in the party’s theoretical pantheon this autumn, sources say, with an eponymous ideological “banner term” likely to be written into the party’s constitution at its national congress.

Such a move would place Xi on a par with late leaders Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping, and analysts said that would speak volumes about his consolidation of power.

However, with the party’s 19th national congress still more than half a year away, giving time for possible resistance and intense horse-trading within the top echelon of power, they said it was too early to say Xi would definitely be put alongside Mao, the founding father of communist China, and Deng, who transformed and opened up the country’s economy. The party congress will mark the end of Xi’s first five-year term in power and see a major reshuffle of the party’s top leadership.

In a symbolic practice formally recognising their ideological contribution and standing within the party, every key Chinese leader since 1949, from Mao to Deng, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, has had their political theory written into the party constitution at a national congress, adding to the party’s ever-expanding “guiding ideology”.

Bo Zhiyue, an expert on party politics, said ideological power was one of three key powers that had to be acquired to become an undisputed leader, with the other two being power over personnel and the military.

“If you are a thinker and have control over ideology, then you will have control over policy directions,” he said. “That’s very critical.

“That’s why Deng was so powerful [in the 1990s]. Even though he did not have a position as the general secretary or the president, he had a final say over policy directions.”

A source at a government think tank said it would most likely be Xi’s turn to have his political theory written into the party constitution this year, with a banner term bearing his name.

A senior media source in Beijing and a well-connected business source concurred, but none of the sources were willing to hazard a guess at exactly what term might be used.

Although the exact wording might not have been nailed down, an ideological banner term bearing Xi’s name would place him above his two immediate predecessors, whose contributions do not bear their names.

Hu’s “Scientific Outlook on Development” was written into the party constitution during the party’s 17th national congress at the end of his first term in 2007, and Jiang’s “Three Represents” at the 16th congress five years earlier, when he retired as the party’s general secretary.

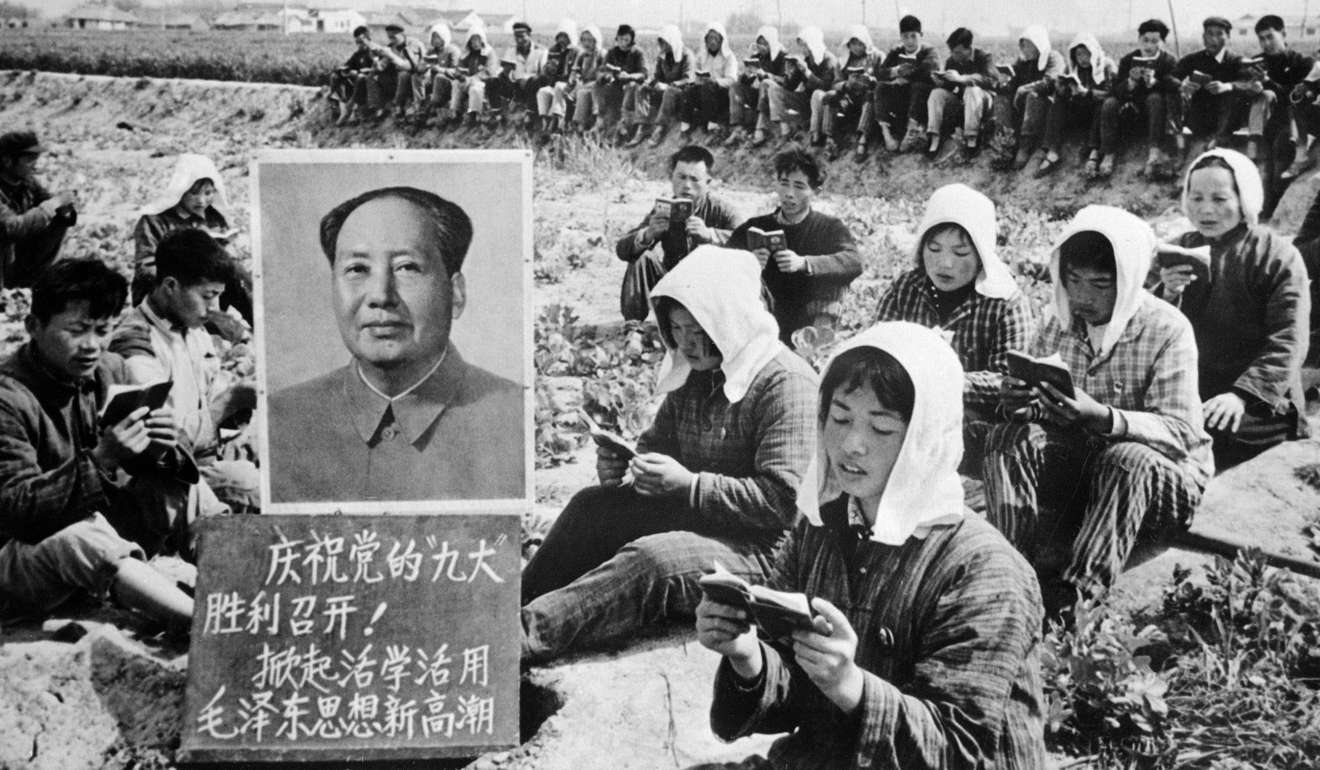

Deng’s “Deng Xiaoping Theory” was written into the party constitution at the 15th national congress in 1997, after his death earlier that year. Mao’s “Mao Zedong Thought” became a guiding ideology of the party in its constitution in 1945, four years before the founding of the People’s Republic. It was left out in a revision of the constitution at the party’s 8th national congress in 1956, but put back in again in 1969.

If Xi has his name written into the party constitution as a guiding theory at this year’s congress, he will be the first Chinese leader since Mao to have done so while in power.

Steve Tsang, director of the SOAS China Institute at the University of London, said that if Xi got his name written into the party constitution, he would “clearly trying to put himself above all other post-Deng leaders and project himself as comparable as a leader to Deng”.

Xi was anointed “the core” of the party leadership at a key meeting last autumn, putting him above his immediate predecessor Hu, who never won such status.

Since taking the helm in late 2012, Xi has amassed power at a speed and scale unseen in recent decades, purging political rivals, gaining sweeping control over the party and the military, and taking the power to make decisions on the economy, diplomacy and security into his own hands.

The enshrining of his name in the party’s guiding ideology would be a “very powerful signal” to the party and the country, Tsang said.

“Achieving this will amount to Xi declaring that he is now in control and will raise expectation that he will implement his reforms to make China great again ... it will suggest to those still resisting him that their resistance is now futile and they should fall in line and support Core Xi – or be prepared to face the consequences,” he said.

But Tsang said he did not think it had all been settled.

“Whether he will succeed in this at the 19th congress is too early to tell,” he said. “There will be resistance to it.”

Chen Daoyin, a political scientist at Shanghai University of Political Science and Law, said Xi saw himself as “shoulder to shoulder” with Mao and Deng and ready to start his own era.

“Since the founding of [the People’s Republic of] China in 1949, we’ve had 30 years under Mao and 30 years under [the influence of] Deng, and now Xi is having his 30 years,” he said.

During this month’s annual meetings of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC) – known as the “two sessions” – influential party princeling Kong Dan told a Central Party School newspaper that Xi would “unlock the fourth historical period of the Communist Party”, which would be a period of “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”.

The party officially divides its more than nine decades of history into three periods. The first two are the “period of new democratic revolution” and the “period of socialist revolution and construction” under Mao, while the third is the “new period of reform and opening up and socialist modernisation” under Deng, Jiang and Hu.

Shortly after ascending to power in 2012, Xi put forward the concept of the “Chinese dream”, which he defined as the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”.

“This is how he sees himself – his role and his position – in the party’s history: to lead the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” Chen said. “It is natural that he would want his name written [into the guiding ideology of the party] like Mao and Deng.”

As was the case with his predecessors, China’s propaganda apparatus has begun acclaiming Xi’s political theory long before the party congress.

On the eve of the CPPCC session, Xinhua, the state news agency published an article in English headlined “China’s two sessions to highlight Xi’s thoughts”.

The article extolled Xi’s thoughts on governance for guiding China’s development in the past four years and stressed the importance of safeguarding his “core” status and concluded with a quote from Wen Yang, a researcher with the Institute of China Studies at Shanghai’s Fudan University, who said Xi’s thoughts on governance would become “an important theme” of both the “two sessions” and the party congress.

Then, towards the end of the two sessions, state broadcaster China Central Television and Cancao Xiaoxi, a newspaper run by Xinhua, said Xi’s “governance ideas” had been threaded through the NPC and CPPCC meetings.

Heavyweight party theoreticians and Marxist scholars have been cheering Xi’s thoughts on governance as “the latest achievement of the Sinicization of Marxism” since early last year.

In the party lexicon, the theoretical legacies of Mao, Deng, Jiang and Hu are all celebrated as such achievements. The term “Sinicization of Marxism” was first coined by Mao in 1938 to describe the tailoring of Marxism to China’s circumstances, with Mao Zedong Thought later upheld as its “first historical leap”.

The Beijing Daily published a lengthy article by Li Junru, a prominent party theoretician and retired vice-president of the Central Party School, in January last year that hailed Xi’s thoughts on governance as a “scientific system” – a status shared by the theoretical achievements of his predecessors. Li concluded the article by calling Xi’s thoughts on governance “the latest achievement of the Sinicization of Marxism”.

Wang Weiguang, the head of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, the central government’s top think tank, made the same argument in a much more prominent and straightforward manner in a book published in July. Xi’ thoughts on governance were acclaimed as “the latest achievement of the Sinicization of Marxism” in bold red letters on an otherwise plain cover.

More than six million copies of a collection of Xi’s speeches since he rose to power, Xi Jinping: The Governance of China, have been sold around the world since it was published in September 2014.

Additional reporting by Choi Chi-yuk