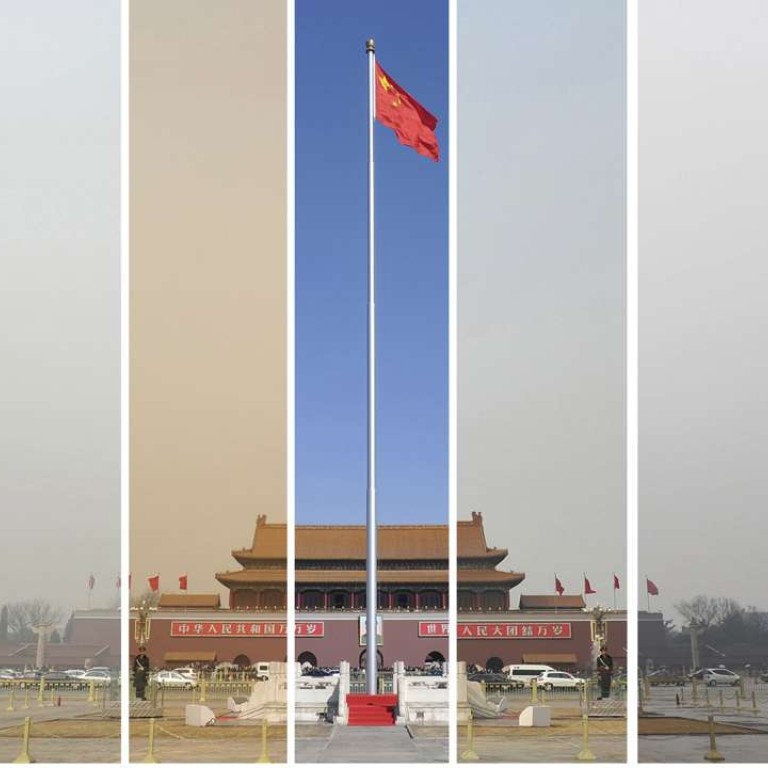

How China’s quick blue-sky fixes make pollution worse

Study finds polluters promptly pick up their bad old ways as focus returns to economic output

Blue skies created by short-term air pollution fixing campaigns ahead of political events are usually followed by a dramatic deterioration in air quality – often worse than before – when the events are over, a study has found.

In the first study of the side effects of such clean air drives, the authors also found they are now used widely by local governments across the nation, apparently inspired by similar moves from central authorities ahead of the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Beijing in 2014 and a grand military parade a year later, said lead author Guo Feng from Peking University.

Watch: Various parts of China are enveloped in thick, white fog

Local governments often made it their mission to ensure clear skies during major political events, only to focus on economic development afterwards, resulting in the return of the pollution, according to the paper published in the journal China Industrial Economics.

Mainland citizens, growing more frustrated with poor air quality, invent sarcastic descriptions of the drastic steps to clean air for political events, such as “APEC blue” – which convey the impression that the efforts would not be long-lasting.

President Xi Jinping said he checked Beijing’s pollution first thing every morning during the APEC summit, and was confident the blue sky would not be short-lived.

The academic paper was published in May, but caught public attention on social media lately as northern China is once again shrouded in winter smog.

The authors examined official air quality data in 189 mainland cities from December 2013 to March 2016 during their annual legislative and political consultation sessions, usually taking place in January or February.

The Average Air Quality Index during the annual political sessions in these cities, which last about five days, was about 4.8 per cent lower than average levels during that time of the year.

But readings during the five days following the political meetings turned out to be 8.2 per cent higher than average levels, suggesting the deterioration was worse than the improvement, according to the paper.

The remedial plans usually include temporarily shutting down polluting factories and taking vehicles off the roads.

“There tends to be a ‘retaliatory pollution’ period after political meetings when factories maximize production to compensate economic losses during the ordered shut down,” said Guo.

“Our findings suggest that while ‘political blue sky’ is easy to achieve with short-term fixes, it comes with a heavy price of worsening pollution, and cannot truly solve the smog problem.”

Guo said the paper’s findings are deemed too sensitive by some mainland media outlets who do not want “a public discussion” on the issue.

He said the study was inspired by “APEC blue” and “military parade blue” in 2014 and 2015, when Beijing’s air quality was so good that the public created nicknames in their honour.

The first large-scale clean-up measures on the mainland took place ahead of the 2008 Beijing Olympics. About 10 months before the event, dirty factories in six provinces around Beijing were ordered to close or partly halt production. These were in addition to Beijing’s efforts to move major polluters – including a large steel mill – to Hebei province.

Yet Peking University professor Chen Songxi said relocating Beijing’s factories to Hebei was a main factor in the capital’s current smog crisis. Authorities underestimated how much pollution would be transmitted from Hebei to Beijing.