Loneliness: the latest economic niche opening up in China

Young people in big cities ‘seeking emotional outlets by embracing loneliness and consuming loneliness’, report finds

Kelly Hui, a 26-year-old photographer, shares a 60 square metre flat in Shenzhen with a flatmate, but they seldom talk.

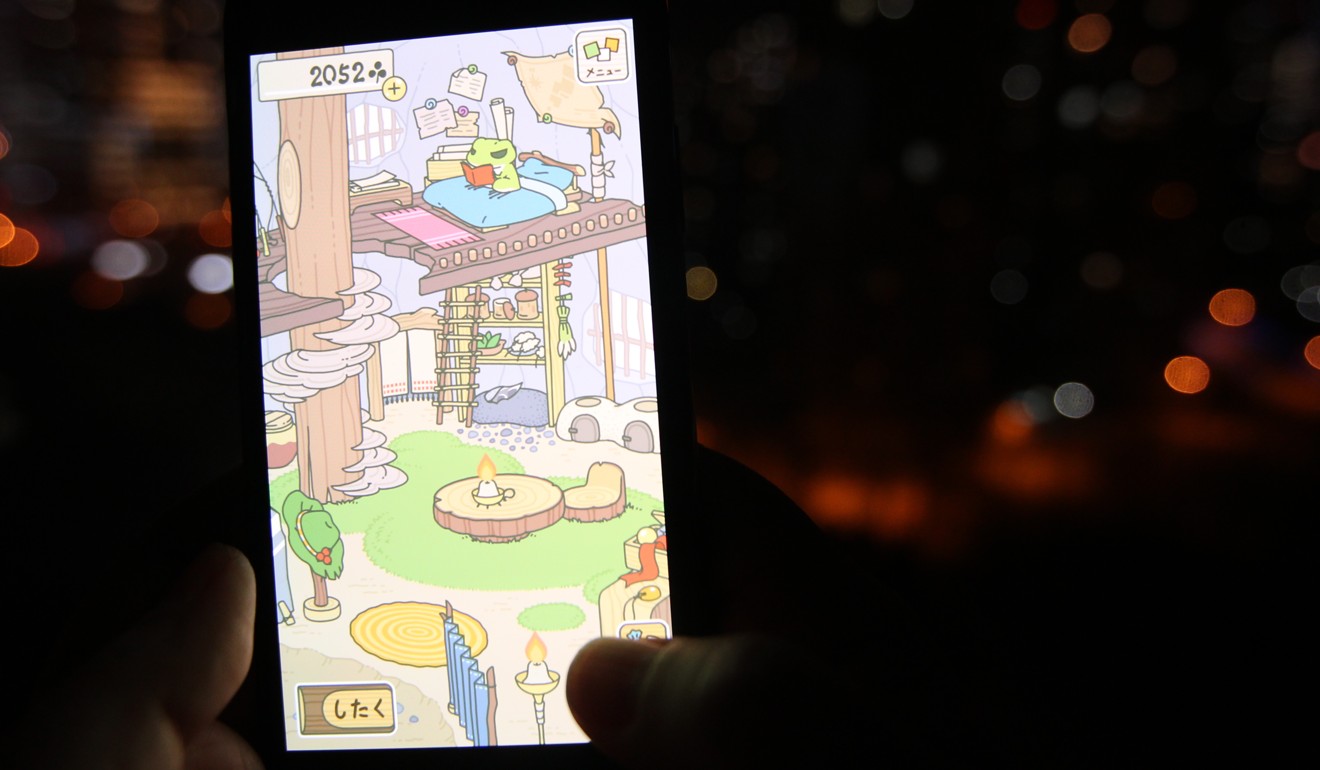

Her most constant companion is, instead, a virtual frog found in the Japanese smartphone game Tabikaeru: Travel Frog.

Even though there is no official Chinese version available yet, the game has been the top free simulation game on the mainland Apple App Store for months. The game has been downloaded more than 10 million times around the world in the three months since it was launched in November, according to developer Hit Point, with Chinese players accounting for 95 per cent of those downloads.

The main protagonist is a frog that goes on adventures around Japan. Players collect clover that grows in the frog’s garden so they can buy supplies for the frog’s journeys.

In return, the frog sends players souvenirs and snapshots during its trips. Users cannot control when the frog chooses to go on its adventures.

“I hadn’t heard from it for three days, so when I received a postcard from the frog I burst into tears,” Hui said. “It is a dear friend to me.

“Also, many times, I feel it is me, being independent and doing whatever I like to do alone.”

Hui represents a new type of Chinese consumer: well-educated, young and willing to spend – but spending alone.

The “empty nest youth” is an emerging theme in the Chinese economy, according to the first Economy of Loneliness report released in January by Momo, a dating application and operator of the mainland’s largest video streaming platform, and Xiaozhu, a home-sharing app similar to Airbnb.

The report says such young people are “usually single”, “renting a flat” and “living in a city away from their family and relatives”.

“The stress to survive and succeed in big cities exacerbates their feeling of loneliness, and they are seeking emotional outlets by embracing loneliness and consuming loneliness,” the report said.

About 67 per cent of the more than 10,000 people younger than 47 surveyed by the institute last year said they watched television or movies to shed their loneliness; more than 49 per cent played smartphone games; 46 per cent went to a bar; 39 per cent went to a gym and nearly 25 per cent listened to music or sang karaoke.

While there are no clear estimates of the size of China’s “loneliness economy”, many businesses, from hotpot restaurants to entertainment equipment makers, are trying to profit from the lifestyle.

Mini karaoke booths, tucked away in shopping malls, cinemas, airports and even subway stations, have mushroomed across Chinese cities in the past three years. The booths, usually equipped with an air conditioner, a couple of chairs and headsets, are similar to traditional karaoke bars, but in a smaller, more intimate environment.

Scanning a QR code, twenty-something Zuo Yiran paid 25 yuan (US$4) via her mobile wallet to sing for 15 minutes in a mini karaoke in a corner of a supermarket in Beijing on a Sunday afternoon.

“I just planned to buy some snacks,” she said. “Tempted by the mini karaoke, I sang eight songs and it made me feel less bored on this cold winter day.

“It’s cool that you can enjoy yourself wholeheartedly and you don’t have to make conversation or endure others’ microphone obsessions. When you feel like sharing, you can record the songs you sang and send them to your friends through your smartphone.”

There are now at least 20,000 mini karaoke booths operating across the mainland, with the value of the market estimated at 3.18 billion yuan last year, up 93 per cent on 2016, according to iiMedia Research, a Guangzhou-based consulting firm. It predicts 120 per cent growth this year to 7 billion yuan.

Xiabu Xiabu, a hotpot restaurant chain that offers “one person, one pot” outperformed many Hong Kong-listed traditional restaurant operators in the past year, seeing its share price triple.

Technology is making it easier for people to enjoy being alone, with shared gyms springing up in some residential communities in Beijing last year. People can run in the five square metre spaces, which are equipped with a treadmill, TV screen and an air purifier, while watching a video or listening to music, with the outside world shut out by a glass door.

Mark Greeven, associate professor of innovation and entrepreneurship at Zhejiang University, said: “We may see a phenomenon, facilitated by technology, where young Chinese people, especially millennials, are looking for individual experiences and personalised services more than the previous generation; not unlike their peers in other countries.”

Chinese consumers, often faced with long, tedious commutes, tiring jobs and competitive workplaces, found solace in entertainment technology which gave them ways of blowing off steam outside the traditional, relationship-driven society they were part of every day, Greeven said.

“However, I’d argue that technology is facilitating loneliness rather than allowing Chinese consumers to embrace it,” he said. “There is plenty of evidence that youngsters would rather spend time on their smartphones than on playing with friends, dating, working and just hanging around.

“I’m not against technology at all, it is one of the wonders of our society, but the slightly addictive nature of certain social networks and the fact that a handful of technology giants control those information streams does make me worry about the long-term societal effects.”

Hu Xingdou, a political economist with Beijing Institute of Technology said: “The loneliness economy in China is expected to become bigger than Japan’s, even though loneliness is the norm there as the country has been suffering from a serious ageing problem for a long time amid an alienated interpersonal relationship culture.”

In China, hundreds of millions of migrants had moved to work in cities amid rapid urbanisation. Intense competition meant they faced severe stresses in their pursuit of success, he said, and they also struggled under a sometimes unfair distribution system that featured rampant corruption and official-businessmen collusion.

“Japanese people have faith in their employers, who they usually serve for their whole lifetime; Western people can work closely with various communities, clubs and charity groups,” Hu said. “While China suppresses the development of non-governmental organisations, Chinese people are destined to be lonelier than people elsewhere.”