Could Manila’s flip-flopping over Reed Bank make Beijing more aggressive?

- How nations react to ‘grey zone’ encounters with foreign aggressors can have a significant impact on their future interactions, says Collin Koh

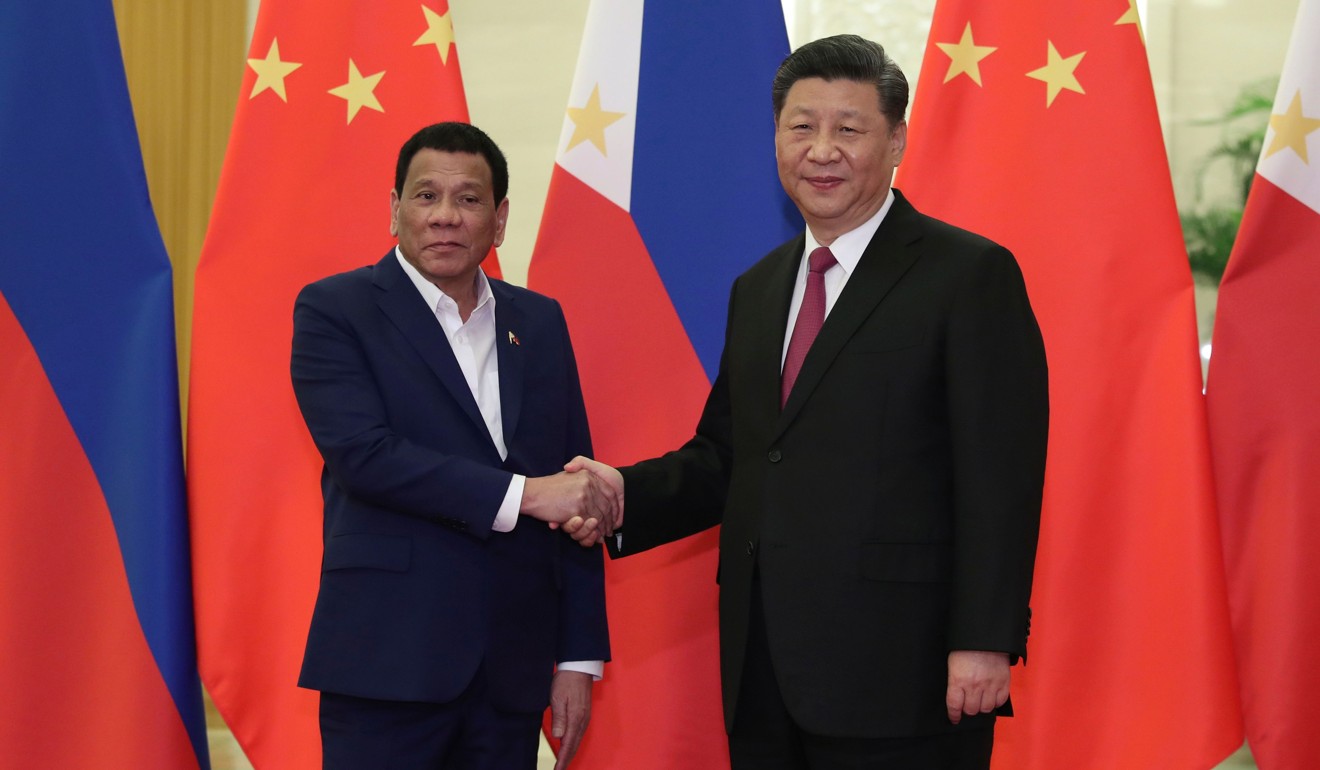

Almost a month on from the ramming of a Philippine fishing boat by a Chinese vessel off Reed Bank, the disquiet in the Philippines has yet to show any signs of ending. But as Beijing and Manila sought to determine what happened on June 9, confusing and sometimes controversial statements emanated from Philippine officials, including President Rodrigo Duterte.

The mercurial leader, who is well known for his often blunt remarks wasn’t the first to respond when news of the incident emerged.

Philippine Defence Minister Delfin Lorenzana initially reacted angrily to the incident, describing it as “intentional” on the part of the Chinese. But when Duterte broke his silence and said it was only a “little maritime accident”, Lorenzana fell in line behind him.

In another twist, the fishing boat’s skipper retracted his initial allegations that the Chinese vessel had intentionally rammed him.

Compared to Manila’s flip-flopping, Beijing has been calibrated and consistent, even if one might question the account of the incident released by the Chinese embassy in Manila, which said the Chinese ship was unable to rescue the 22 fishermen it tipped into the sea because it was “besieged” by Filipino boats.

‘China’s not to be trusted’: Philippines’ Rosario says

Speculations were rife that the Chinese vessel was operated by the maritime militia. Be that as it may, the incident serves as an important lesson on crisis response which carries ramifications for how governments react to future “grey zone” scenarios.

Simply defined, grey zone strategies describe militarised and non-militarised coercive techniques employed by a nation for the attainment of foreign policy objectives without resorting to outright armed conflict. They might include the use of supposedly non-state actors, like the “little green men” who took control of the Crimea in 2014.

The maritime equivalent would be the “little blue men” described by Professor Andrew Erickson in his work on the elusive Chinese maritime militia operating in the South China Sea. The supposedly regular fishermen could fulfil certain so-called patriotic duties in support of Beijing’s assertion of maritime rights and interests in the contested waters.

Grey zone techniques may have a higher chance of success if bureaucratic hurdles hamper an effective response from the victim. Confusion and contradictory internal reactions can lead to the loss of opportunity for a decisive response to avert or overturn the fait accompli dealt by the aggressor.

The confusion that emanated from Manila after the Reed Bank incident wasn’t a one-off. The Philippines’ responses since late 2016 to Chinese militarisation activities in the Spratly Islands have been confusing to say the least. Most notably, in May last year, Manila’s first response to reported Chinese missile deployments to the Spratlys was to “verify” them. This might appear to have been a prudent move, except it took the authorities almost five days to realise that it was unable to verify the supposed transgression.

“There’s a technology that we need that we still don’t have to be able to verify it for ourselves,” then presidential spokesman Harry Roque said, adding that the issue was not even discussed during a cabinet meeting convened by Duterte.

Philippines agrees to joint investigation into fishing boat’s sinking

But the problem is not exclusive to the Philippines. In March 2016, following reports that a fleet of more than 100 Chinese fishing boats had entered Malaysian waters off Sarawak, confusion gripped Kuala Lumpur.

While the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency, or coastguard, said the intrusion did take place, its navy disagreed. The incident happened just months after it had been revealed that China’s coastguard had maintained a presence in the South Luconia Shoal, off Sarawak, since 2013.

Eventually, Kuala Lumpur did submit a diplomatic protest but the lacklustre response likely emboldened Beijing to maintain its coastguard presence in the shoal.

Malaysia’s maritime forces are in a somewhat better shape than their Filipino counterparts, but they are still outmatched by China’s. They managed to put up a presence, albeit intermittent, in the South Luconia Shoal just to demonstrate that China isn’t allowed to reign full control.

In contrast, following the Reed Bank incident, Duterte warned the Philippine Navy to “stay out of trouble”. To compound the situation, Lorenzana said that the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources and not the navy should have responsibility for protecting fishing activities in the South China Sea, despite its obvious limitations.

Duterte-Xi deal on China fishing in Philippine waters ‘not enforceable’

But Southeast Asian nations don’t always lose out in grey zone situations.

In 2014, the Vietnamese stood up to the Chinese in an oil rig dispute in the South China Sea. Even though both sides claimed victory, Hanoi did not succumb to Beijing’s greater military threat.

Similarly, Indonesia responded decisively after the Chinese coastguard intervened in Indonesia’s fishery enforcement action off the Natuna Islands in March 2016 – ramming a Chinese fishing boat.

Soon after the incident, Jakarta issued a strong protest and reinforced its naval presence in the region. Three months later, an Indonesian warship fired warning shots at a transgressing Chinese fishing vessel. Not only were there no more reports of such incidents after that, Indonesia’s trade links with China were unaffected.

The Philippine case typifies how the wrong response can embolden a grey zone aggressor, be it China or anyone else. One could attribute the success of grey zone strategies to the finesse of the aggressor, but the victim’s response also has a significant role to play in determining the outcome.

Collin Koh is research fellow at the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, a unit of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore