Can the US, China and North and South Korea find peace on the peninsula? War veterans hope so

It has been 65 years since an armistice ended the fighting in the Korean war, but a formal peace deal could be closer than ever

While negotiations on how to denuclearise the Korean Peninsula are likely to continue well beyond this week’s historic summit between US President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, a more immediate goal could be a peace treaty to end the Korean war, which technically continues 65 years after an armistice suspended the bloodshed in 1953.

Following Trump’s meeting at the White House earlier this month with North Korean special envoy Kim Yong-chol, the US president said a treaty was “something that could come out of the meeting”.

Observers, meanwhile, said Kim Jong-un was likely to be motivated by the desire to preserve his family’s dynasty, have sanctions lifted and become more open to international investment.

But perhaps those most keenly watching for signs of a treaty are the men from the two Koreas, the United States and China who were directly involved in the three years of bloodshed.

Zhang Zeshi, 89, Chinese, fought on the North Korean side

His experience of the war

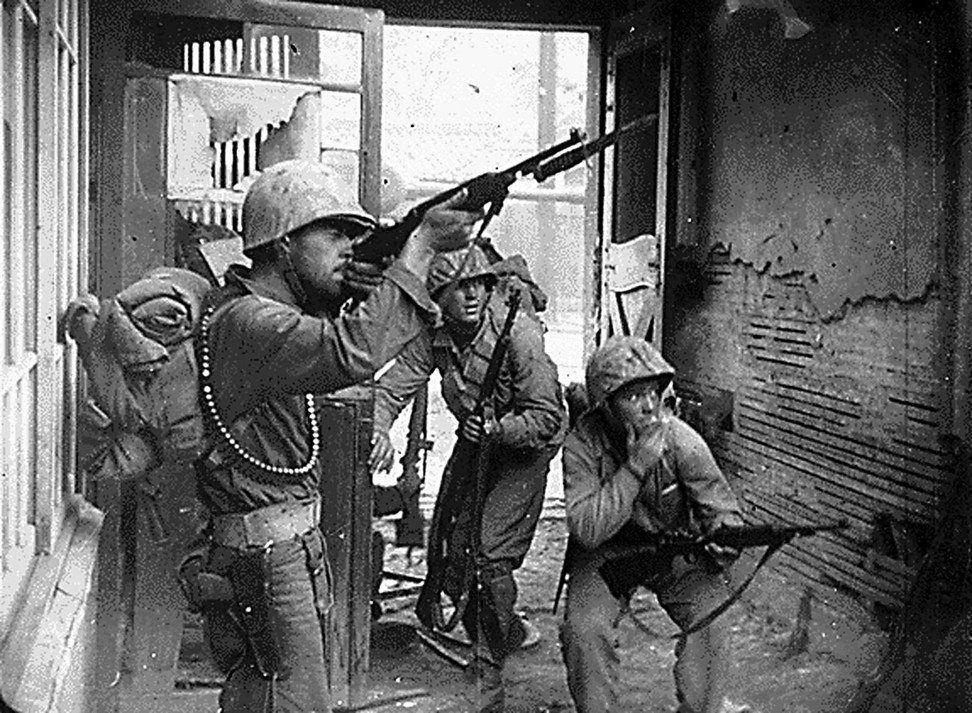

Zhang left his home in China to fight in the Korean war in March 1951. Just a month later he was injured in the Fifth Battle of Seoul and, along with about 3,000 of his comrades, was captured by American troops.

“The Fifth Battle was the most fierce, most difficult one [for the volunteer Chinese army], with the biggest losses. We were besieged by the Americans, and basically finished. A third of us died, another third fled [to North Korea], and the rest, nearly 3,000 people, were captured. I was one of those captured.”

After being taken to a prisoner of war camp he continued to play his part in the conflict by causing as much disruption as he could. His captors’ patience finally ran out when Zhang and 17 other soldiers – two Chinese and 15 North Koreans – staged an uprising and were transferred to a high-security facility, where he stayed until the end of the conflict in 1953 and was sent back to China.

Home was not how he had left it, however. The fact he had been a prisoner of war was regarded as shameful and people were also suspicious about whether his allegiances might have changed during the war. As a result, he was expelled from the Communist Party and it was not until the early 1980s, long after the Cultural Revolution had ended, that he was readmitted.

Before the Korean war, Zhang had studied at Tsinghua University, so after he regained his “rights” he took a job as a teacher. Since then he has also written two memoirs and has been active in raising public awareness of the war.

“There were more than 20,000 [Chinese] prisoners taken during the war. Two-thirds of them were sent to Taiwan and only about a third, or about 7,000, returned to the mainland. These people risked their lives to get back.

“It didn’t occur to me that after I returned to China, I would be classed as a traitor. I was expelled from the party and the army, and got beaten up during every [political] campaign, until the end of the Cultural Revolution.”

On the possibility of a formal peace treaty

“I think both North Korea and South Korea want China to help bring about a joint declaration to finally end of the war.

“They are trying to persuade Kim Jong-un to declare where he stands, but Kim wants the Americans to do the same, to say that they will end the war. But everyone knows that Trump can change his mind. He could take it all back and say he knew North Korea was conducting nuclear tests again. So a declaration without the participation of China would be incomplete and lack a guarantee.

“[A peace treaty] must include China, because China lost the biggest number of soldiers in the war and it signed the ceasefire agreement. A declaration of the end of the war would be better than a ceasefire, but it would be valueless if a permanent peace agreement didn’t follow.”

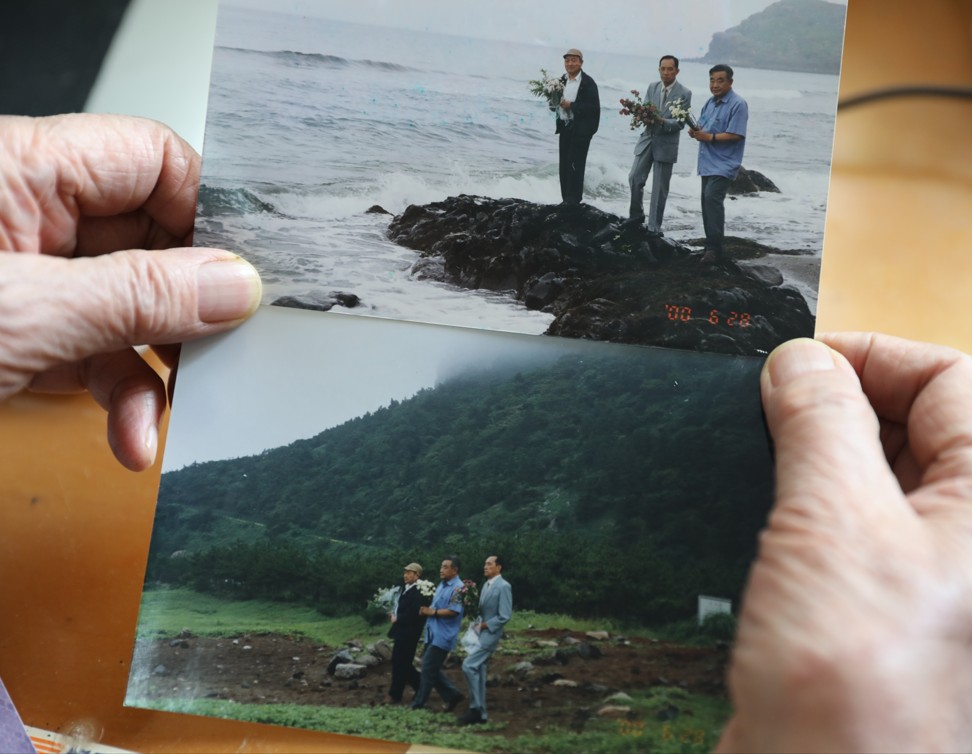

Tiffany Hwang, 29, whose late grandfather, Hwang Song-do, fought on the North Korean side

His experience of the war

“My grandfather, who was born in 1927, fought on the North Korean side. After being captured by the South Koreans he ended up living in the South. He passed away last year so did not get to see the recent changes on the Korean peninsula.

On the possibility of a formal peace treaty

If my grandfather had heard that the two Koreas were discussing an official end to the war, he would have been so happy. He always used to say that there should never be another war on the Korean peninsula. If they can agree a peace treaty it would be the realisation of my grandfather’s wish.

Park Myung-ho, South Korean, fought on the South Korean side

His experience of the war

I served in the 28th Regiment of the 9th Infantry Division during the war.

“I remember we were sent to try and take a mountain in Chinese army territory on the far side of Baengma Hill. We met a huge Chinese resistance and there was a great fight. After a while we were given the order to retreat, which we did. But as we were retreating, the Chinese launched a massive offensive. The fighting was unprecedented, and the advantage went back and to. Baengma Hill changed hands numerous times – we took it 12 times from them, and they took it back 12 times from us. It was a historic battle.”

On the possibility of a formal peace treaty

“The South and North should stop bickering and distrusting one another. We all greatly desire unification. The thought that North Korea can only be our enemy is outdated now. We must move on, and I hope the whole population of 70 million come together as one.”

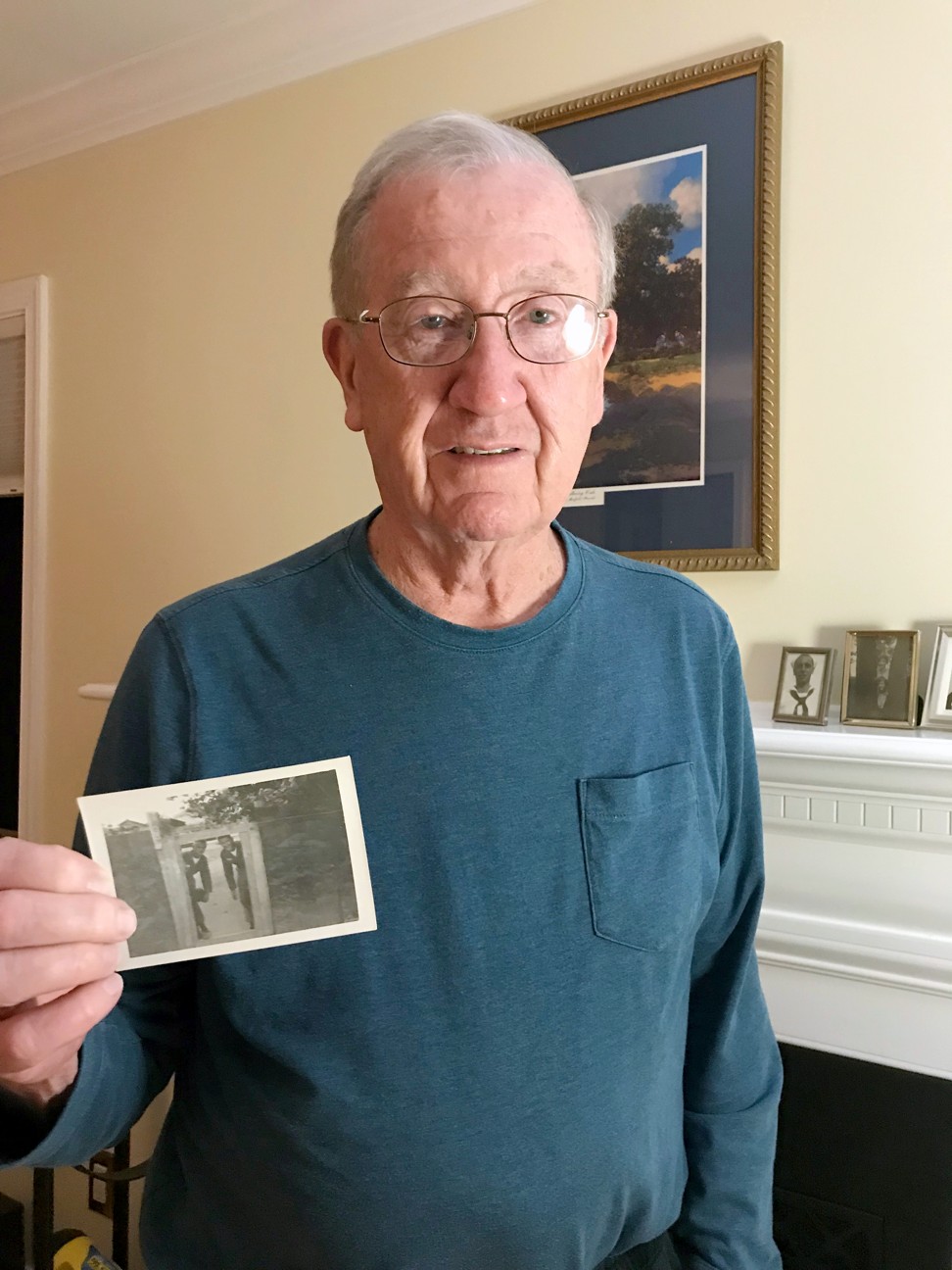

John Joseph Herring, 81, American, fought on the South Korean side

His experience of the war

Herring was dispatched after most of the fighting had died down, and was stationed “a few miles” south of Panmunjom for nearly two years before the ceasefire was signed there.

“We were in the US Army security agency, and we intercepted Korean messages, called ‘traffic’, which were gathered at isolated interception points by another unit using antennae and other audio surveillance devices. There was still a lot of shooting going on then, and I always thought it was very dangerous for those interception units to be out there.”

Herring was intercepting messages from “people who shouldn’t have been in the South, who were spying and sending their findings to North Korea. The O58s, which was the designation for army mechanics who did that job, would intercept the traffic and we would try to translate that into something.

“I went for 48 weeks of school in [an US Army base in] Fort Devens, Massachusetts, learning how to decipher code. You didn’t have to know the language. You just had to know the frequency of vowels and frequency of consonants to know whether the message might be useful.

“We would try to decide whether what they were picking up was a message or whether it was something garbled on purpose. We tried to separate the useful messages from the garble by looking for certain sequences of vowels and consonants.

“Once we got something that we thought made sense, we would send it over to the language boys, who had gone to school to learn Korean. They would try to make more sense of it than we had. Then they’d send them over to the National Security Agency.”

On the possibility of a formal peace treaty

“My feeling has little or nothing to do with what I learned or experienced in Korea. It was just such a different time. It’s like world has moved on too much for that to matter. And I’m too full of Trump to even consider that there will be a successful outcome and I think the other guy [Kim Jong-un] is much savvier than Trump and Trump doesn’t realise it.”

“What feels odd is that I’ve seen pictures of cities in South Korea, like Seoul, with great modern hotels, roads, nightclubs. The idea that the president of the US is sitting down with the head of the North Korean state is odder still because I just never thought that was going to happen.

“I don’t think that sitting down and calling something an armistice versus a ceasefire versus a truce means a whole hell of a lot to anybody.

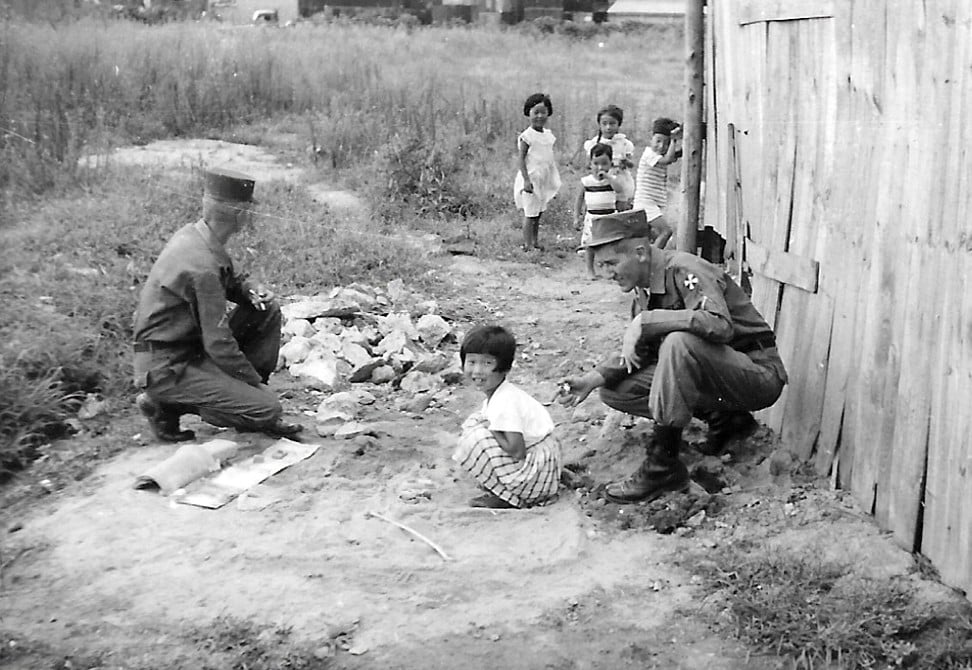

“What I see in images of South Korea today is an unbelievable contrast to what I remember. Everything I remember is like in the pictures. Everything was bombed out with kids not clothed properly running around looking for food and black market places.

“If you wanted, you could get a Cadillac for three cartons of cigarettes. I’m exaggerating but you could get damned near anything you wanted on the black market.

“And there was only one building basically in Seoul and that was the United Nations Club, where all of the soldiers from all of the different countries that had took part during the war would be, drinking and raising hell.”