New | Q&A: Chinese activist scholar Teng Biao on how Occupy Central affects mainland activism

In June, mainland Chinese scholar Teng Biao addressed a crowd of more than 100,000 in a speech at Hong Kong’s Victoria Park to mark the 25th anniversary of the crackdown on the Tiananmen movement in 1989. Four months later, Teng, one of the most prominent advocates in the mainland’s civil rights movement, says he is surprised by the scale of Hong Kong’s current pro-democracy civil disobedience movement.

Speaking by phone from Harvard University, where he is now a visiting research fellow, Teng shares his impressions on Hong Kong’s protests and how they relate to political reform advocacy in the mainland in a conversation

How do you feel about Occupy Central in Hong Kong?

Occupy Central has grown and has turned into Occupy Hong Kong. We never imagined it would reach this scale and become the Umbrella Revolution it now is.

It seems that the demonstrators are in a difficult position; they cannot give in. Emotions have been rising. Many more joined when they saw police use tear gas. The government can also not give in. It is very clear that it is naïve to expect they would allow genuine universal suffrage in Hong Kong. There is a also concern [in the government] that the democracy issue could spread to other parts of China.

What do you expect the outcome of the protests in Hong Kong will be?

It is very difficult to say, both sides don’t compromise. The likelihood of violence continues to exist and could even increase as protests continue. Of course, one important demand by the protesters is for Leung Chun-ying to step down as chief executive.

I think his resignation is something Beijing could accept, even though it won’t be easy to accept. But his resignation would not in any way affect Hong Kong’s democratisation process. They swap the man, but don’t swap the system.

There has been much talk about anti-mainland sentiment in Hong Kong. What role do you see it play in the current protests?

The impact of indigenisation (本土化) in Hong Kong is certainly getting bigger and bigger. But the main demand among protesters relates to the free election of Hong Kong’s chief executive in 2017. So, I think, some anti-mainland sentiment is part of this movement, but it is certainly not dominant.

Firstly, because the independence of Hong Kong is impossible. Secondly, because Hongkongers see that many people in the mainland support this movement in Hong Kong.

What is the sentiment on Occupy among advocates for political reform in the mainland you have talked to?

Many people in the mainland, including human rights defenders and activists, are looking at what is happening in Hong Kong. It is not only a crucial moment in the democratisation of Hong Kong, it is also an opportunity to promote democratisation in the mainland. They know that they and those in this Umbrella Revolution are challenging the same [thing] -- the Communist Party’s autocratic rule. I think, Hong Kong’s political movement [for political reform] and the mainland’s have become closer. Like I said in Victoria Park, if the mainland doesn’t have democracy, Hong Kong will never have real democracy.

How do you think Occupy will affect the Chinese leadership’s attitude to domestic dissent?

I worry that persecution will intensify. The government’s persecution of dissent in the mainland has been strict and has become more so over the last year. They can only become more anxious, fearing that there is a domestic threat to their rule. It is very hard to predict what will happen in the mainland, but it is certain that Hong Kong will be affected by the increasing persecution on the mainland.

The central leadership might make some compromises in the process, but these could also give them space to manipulate. In moments of great pressure, they could make some promises, but once that crisis is over, who can keep them from breaking the promises?

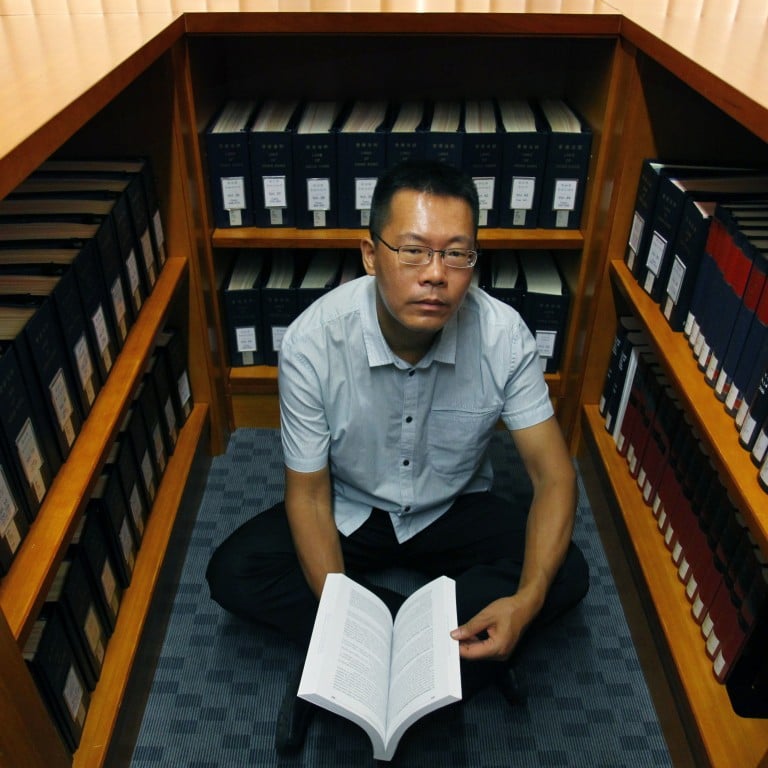

Teng Biao, 41, gained prominence for successfully challenging the illegal detention of migrant workers after one such worker, Sun Zhigang, died in police custody in Guangzhou in 2003. Over the years, the law lecturer at China University of Political Science and Law and civil-rights lawyer was involved in the New Citizen Movement, which calls for the protection of citizens’ rights enshrined in the Chinese constitution, and for more government transparency. Before he joined Harvard earlier this year, he was a visiting scholar at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. This transcript was slightly edited for clarity.