Exhibitions uncover Hong Kong’s hidden history of printmaking, from movable type to modern lithography

- Two exhibitions at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum turn the spotlight on a forgotten part of the city’s artistic identity

- The shows feature rare works from the 19th century as well as experimental, contemporary pieces that redefine the medium

With the world now so reliant on computers, it is easy to forget that typesetting and colour printing used to be labours of love that required days, weeks or even months to achieve precise results. The younger generations also may not be aware that Hong Kong was once a hub for the art of printing.

The ongoing exhibitions “Between the Lines – The Legends of Hong Kong Printing” and “20/20 Hong Kong Print Art Exhibition” – which both opened last October at the Hong Kong Heritage Museum – share the compelling history of printing in the city, beginning with rare prints and metal movable type from the 19th century and continuing through to recent developments in the local contemporary art scene.

The two shows enrich our understanding of the medium while also celebrating printmakers’ contributions to Hong Kong’s artistic identity. They are co-presented by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department and the Hong Kong Open Printshop, an artist-run, non-profit organisation based at the Jockey Club Creative Arts Centre in Shek Kip Mei.

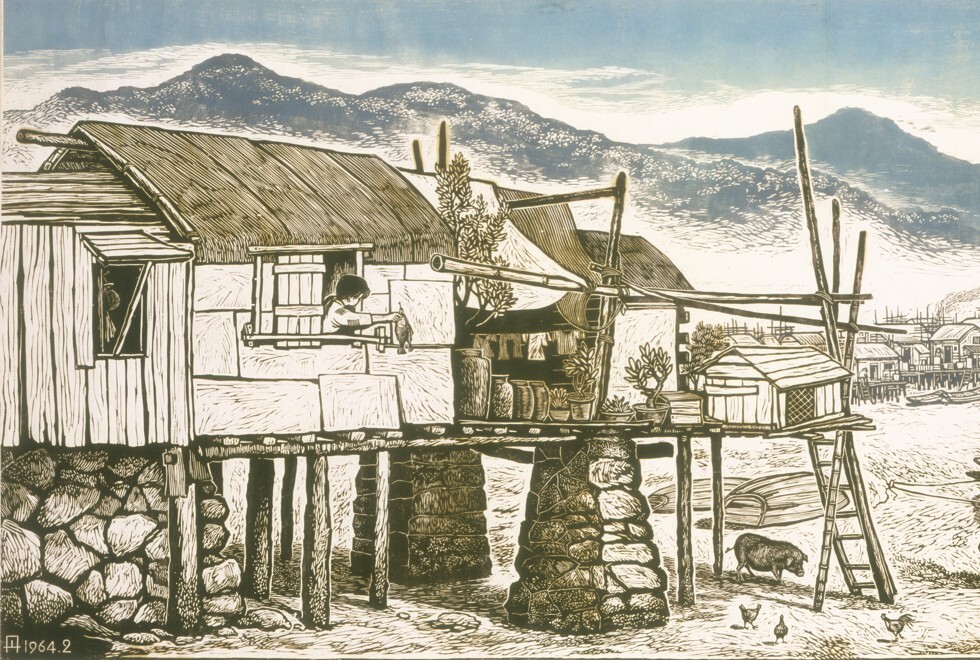

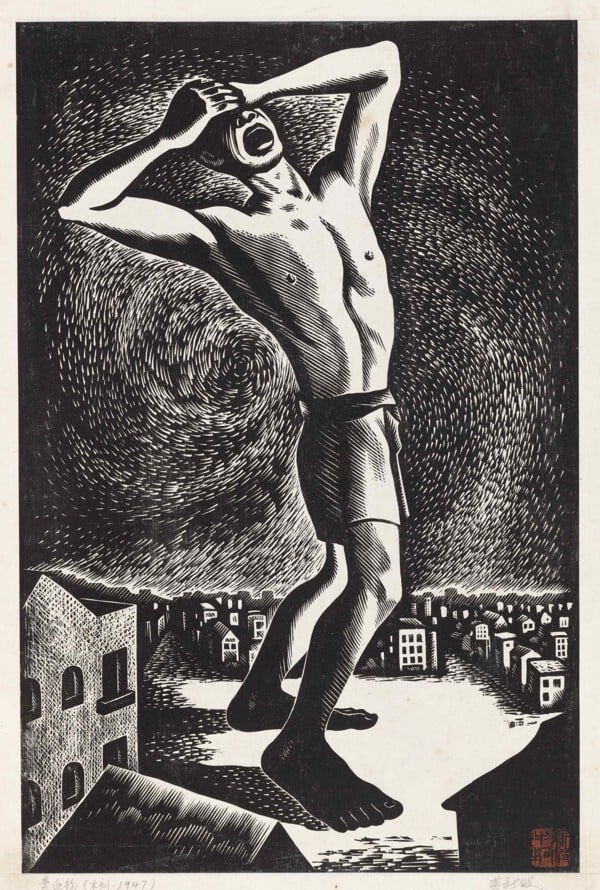

From striking post-war portraits of labourers toiling by a wharf on Hong Kong Island to a sleepy, 1960s-era scene in the fishing village of Tai O, Hong Kong printmakers quietly documented everyday life in the city for decades. They used labour-intensive processes to create powerful works of art – gouging, scratching and stencilling images on various surfaces to be pressed on paper.

“Hong Kong art has actually been very interesting for some time, but we have not had enough exhibitions of this kind that showcase achievements in different media,” says David Clarke, honorary professor of art history at the University of Hong Kong and an artist participating in the “20/20” exhibition.

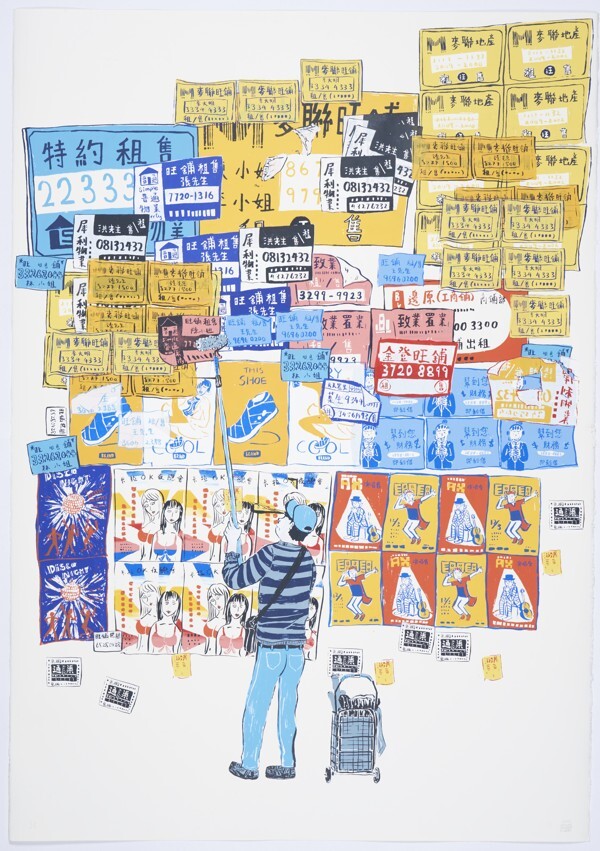

Celebrating the 20th anniversary of the Hong Kong Heritage Museum and the Hong Kong Open Printshop, “20/20” features a treasure trove of prints from the 1940s up to 2020. On view are works from emerging names such as illustrator and screenprinter Onion Peterman, alongside pieces by established figures in Hong Kong art history such as the late modernist painter Gaylord Chan.

The show is structured around 20 questions about various printmaking processes and how masters of this medium have impacted the local art scene. Each question is answered with a set of artworks, accompanied by explanations of the intricate techniques involved.

The bulk of the show features woodcuts, etchings, lithographs and other prints made using techniques developed centuries ago, but several artists have reinterpreted these traditional processes to create modern works – some have even combined them with technologies such as augmented reality and animation. Young illustrators and designers are also taking part, showing zines, posters and craft items.

“It is important to put printmaking in a contemporary context,” says Yung Sau-mui, a lithograph artist who is also programme director of the Hong Kong Open Printshop. “This connects it to the new generation so it’s not a relic [of the past].”

Clarke, for instance, swapped the traditional printing press for a photocopier when working on People I don't know who have the same name as me, a piece exploring the concept of identity. After gathering internet pictures of people also named David Clarke, he photocopied them repeatedly until he was left with a series of distorted images that evoke line drawings.

“Rather than working in a studio, I do a kind of a hit-and-run approach of making my art in everyday office spaces,” Clarke says. “What interests me is to engage with technologies of mass reproduction.”

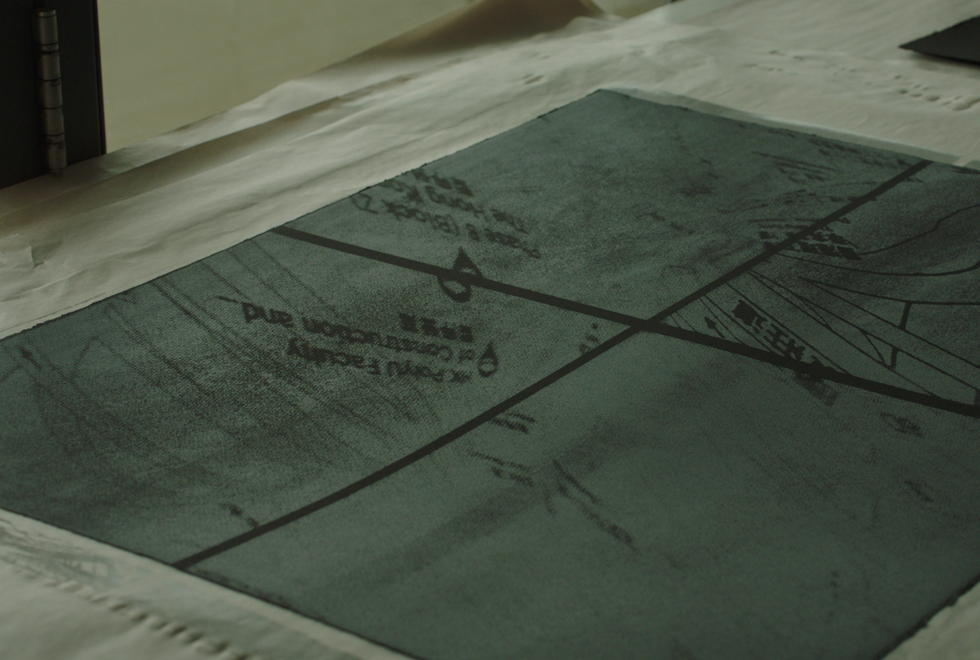

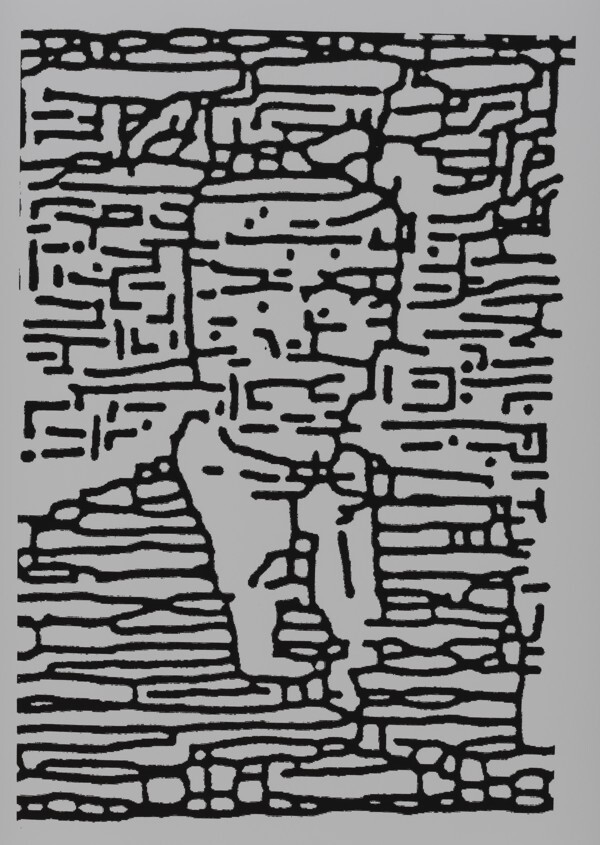

Yung has also adopted an experimental approach in her artwork, taking printed images of Hong Kong streets from maps in the Hong Kong Guide as well as Google Maps, manipulating them using Adobe Photoshop, then transferring them to aluminium plates to make lithograph prints. These works, titled Mapping, explore Hong Kong’s colonial history as reflected in the names of the city’s streets and neighbourhoods.

“Maps have quite a lot of symbolic meaning,” Yung says. “When we are lost, we need them, and they are also a form of authority and can mark your territory.”

Unlike woodcuts or etchings – for which indentations and grooves are cut into a surface, then pressed to create a print – lithography relies on subtle chemical processes to form a printed image one colour at a time.

Traditional lithograph printmakers first wash and grind a thick slab of limestone before using oil-based materials like crayons to draw an image on its surface. A chemical solution is then applied to develop the image on the stone before it’s inked and pressed. The process is repeated to layer different colours on the print. Today, aluminium plates are regularly used to make lithograph prints instead of the limestone slabs.

“When lithography was first invented, it was a breakthrough,” Yung says, noting that its emergence from the late 18th century provided the first means for mass-produced prints.

“Nowadays, you can just buy a nice printer yourself,” she adds. “But we can’t imagine, in the old days, how much effort and how much investment it took to make prints in bulk. It was a totally different world.”

Yung is also the curator of the “Between the Lines” exhibition. Her curiosity about the origins of printing in Hong Kong and how lithography arrived in China inspired her to mount the show.

The exhibition presents the story of how British missionary Robert Morrison brought both movable type and the lithographic press to China in the 19th century, and also traces the subsequent development of printing in Hong Kong. Rare posters and early publications made during this era are featured.

The world’s oldest dated printed book in existence is believed to be from China. It was printed during the Tang dynasty (618-907), using delicately carved woodblocks. This printing technique was further developed in Europe with reusable metal pieces called movable type, and was eventually introduced in Hong Kong.

For Yung, the highlight of curating the show was discovering that a beautiful set of Chinese movable type had been crafted over decades in Hong Kong and then sold for use in several countries including the Netherlands, Russia and Australia.

“None of us had heard about the story of the Hong Kong movable type,” she says. “It was cast in Hong Kong in the mid-19th century at Anglo-Chinese College in Central [renamed Ying Wa College in 1914]. And because it was the first complete set [of its kind], it had a really significant impact on the rest of the world.” The type helped build a bridge between cultures, as it was used to print texts such as bilingual dictionaries.

Although the original set of movable type was lost, Yung and her team managed to cast a duplicate set of the Hong Kong Type, which is displayed in the “Between the Lines” exhibition. Also on view are recent examples of traditional letterpress printing by designers and craftsmen looking to preserve the vanishing craft, which originated in the 14th century.

Viewed together, the two exhibitions bring to life the fascinating yet little-known evolution of printing in Hong Kong. “It’s an amazing legacy that we have,” Yung says. “It’s our story that we can pass on to generations to come.”