The legendary Lei family of architects who built China’s world heritage sites

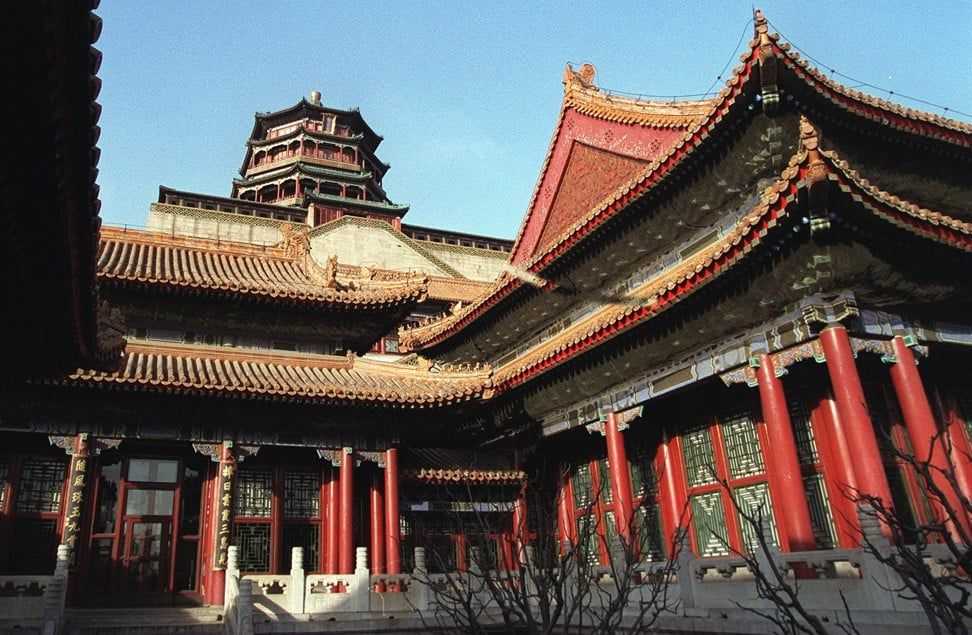

Twenty years ago, China’s Summer Palace and the Temple of Heaven in the capital, Beijing, were placed on the list of Unesco’s protected cultural World Heritage Sites.

Beijing’s Forbidden City and Hebei province’s Chengde’s mountain resort and its outlying temples – originally used as a summer palace – and the Western and Eastern Qing Tombs were also added to the list by the specialised UN agency in 1987, 1994 and 2000, respectively.

Many people around the world will have heard of most of these renowned sites because they are all popular tourist attractions.

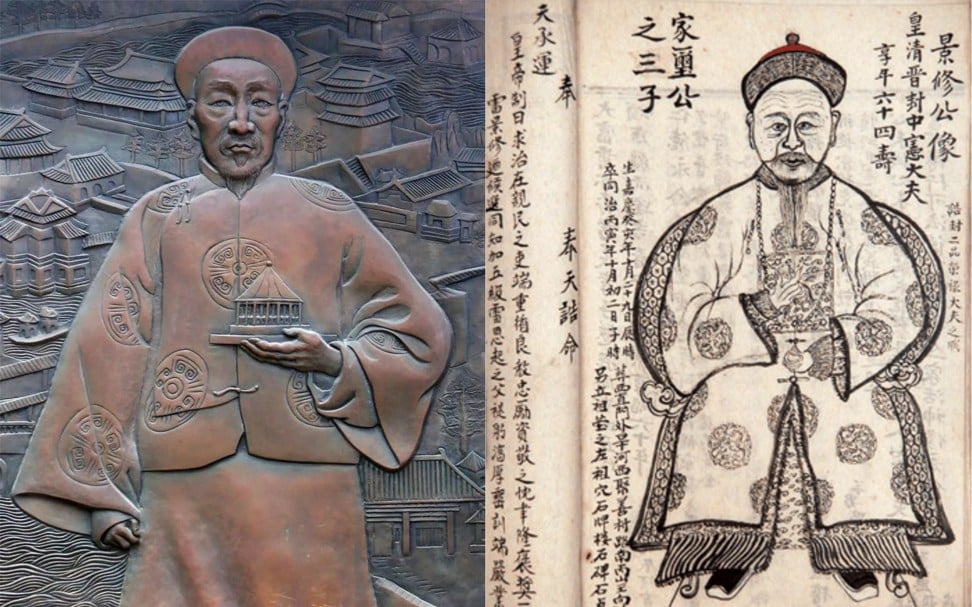

However, few people will know that all five sites were created and built by a dozen members of the Lei family of architects for eight generations, who presided over the design of imperial buildings for 200 years up to the end of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911).

Today, these imperial palaces, gardens and mausoleums are known in Chinese as Yangshi Lei, meaning “Lei style” architecture.

Up to 2017, there were 36 sites in China that had been listed as Unesco World Heritage Sites, which means that almost one seventh of these buildings were created by the Lei family craftsmanship.

An archive of the preserved blueprints and construction models of the imperial palaces, bequeathed by the Lei family, has also been recognised by Unesco in its Memory of the World Register.

The Chinese phrase, “The Lei family, in a sense, represents half of China’s architectural history”, acknowledges the Lei family’s contribution to the nation’s heritage.

Here we take a closer look at five things linked to these Chinese architecture and historic sites and the work of the Lei family over the years.

1. The clan’s innovative ancestor impressed Emperor Kangxi

In 1683, during the reign of Emperor Kangxi, who ruled from February 1661 to December 1722, the Ministry of Works was recruiting skilled artisans from all over China to help build the imperial gardens.

Lei Fada, a carpenter came from Jiangxi province, went to Beijing and was recruited.

During the renovation of three halls at the Forbidden City – originally built during the Ming dynasty – Lei, who was then in his 60s, stood out from among the artisans and impressed the emperor with his innovative ideas.

Lei became the imperial architect at the Ministry of Works.

His designs placed the most important structures along a central axis and maintained their symmetry, while the less important structures, situated on both sides, were also roughly symmetrical to ensure a sense of uniformity and make them architecturally distinctive.

The emperor was impressed with his ideas and felt he had succeeded in conveying the Chinese philosophy of using the “middle way” to find a balance been excess and deficiency, and achieve a sense of peace and harmony.

2. Lei clan invented ‘doukou’ construction structure still used today

After Lei’s death, his son Lei Jinyu took over his duties as imperial architect at the ministry.

Jinyu’s talents led Emperor Kangxi to appoint him as chief architect of the Imperial Works under the Imperial Household Department.

He was also the chief architect of the Yuanmingyuan expansion project when Emperor Yongzheng ascended the throne in 1723.

As the chief architect, Jinyu had the opportunity to display all of his talents and made the Lei family more widely known. He also invented a construction technique called “doukou”.

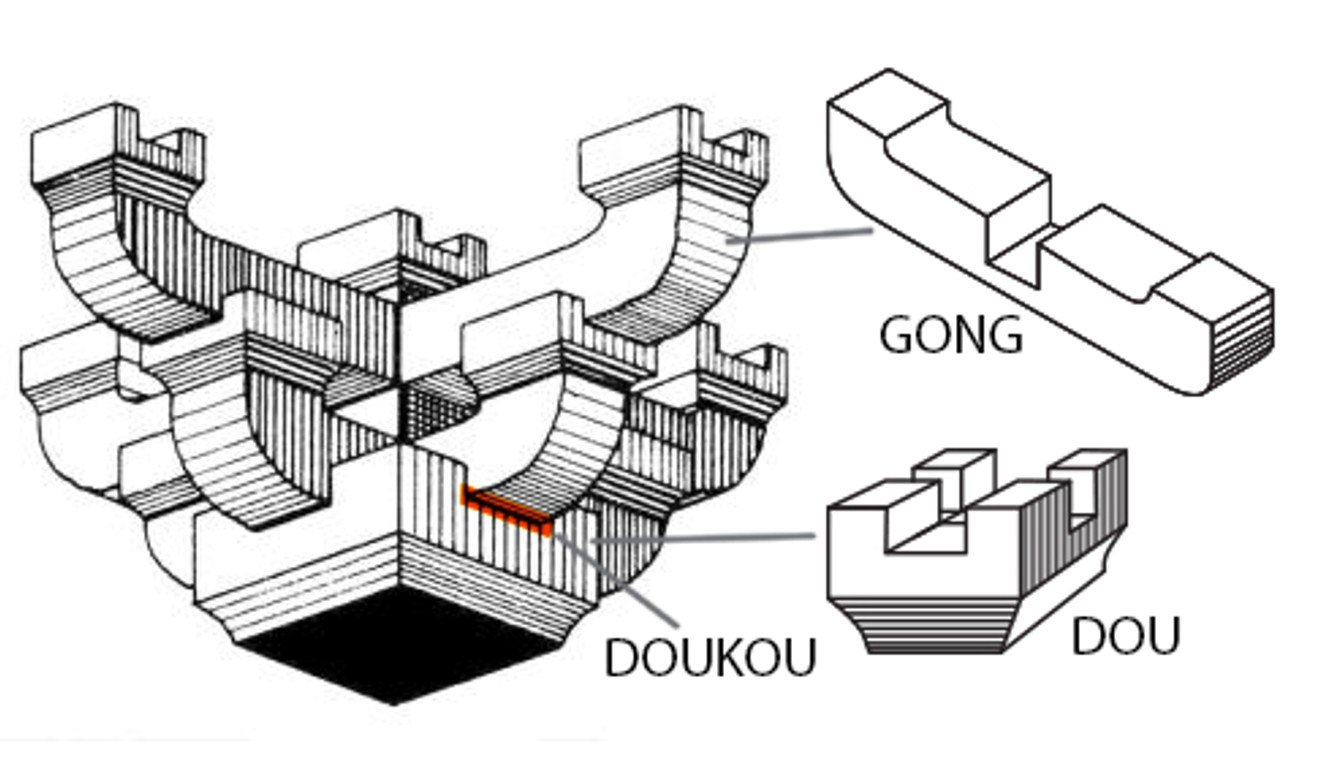

Traditional Chinese architecture at the time used a structure called a “dougong” – interlocking, weight-bearing wooden brackets placed between the tops of columns and cross-beams.

It had been widely adopted in the construction of buildings since the period of Chinese history known as the Spring and Autumn period, from about 771 to 476 BC.

Based on the original idea of dougong, Jinyu decided to standardise the width of each “doukou” – the mortice, or hole, created to receive the connecting interlocking parts – which made the structure more precise and robust.

It proved strong enough to withstand earthquake tremors.

Jinyu’s new doukou became the basic unit for calculating the thickness and height of columns and beams in construction, which is still in use today.

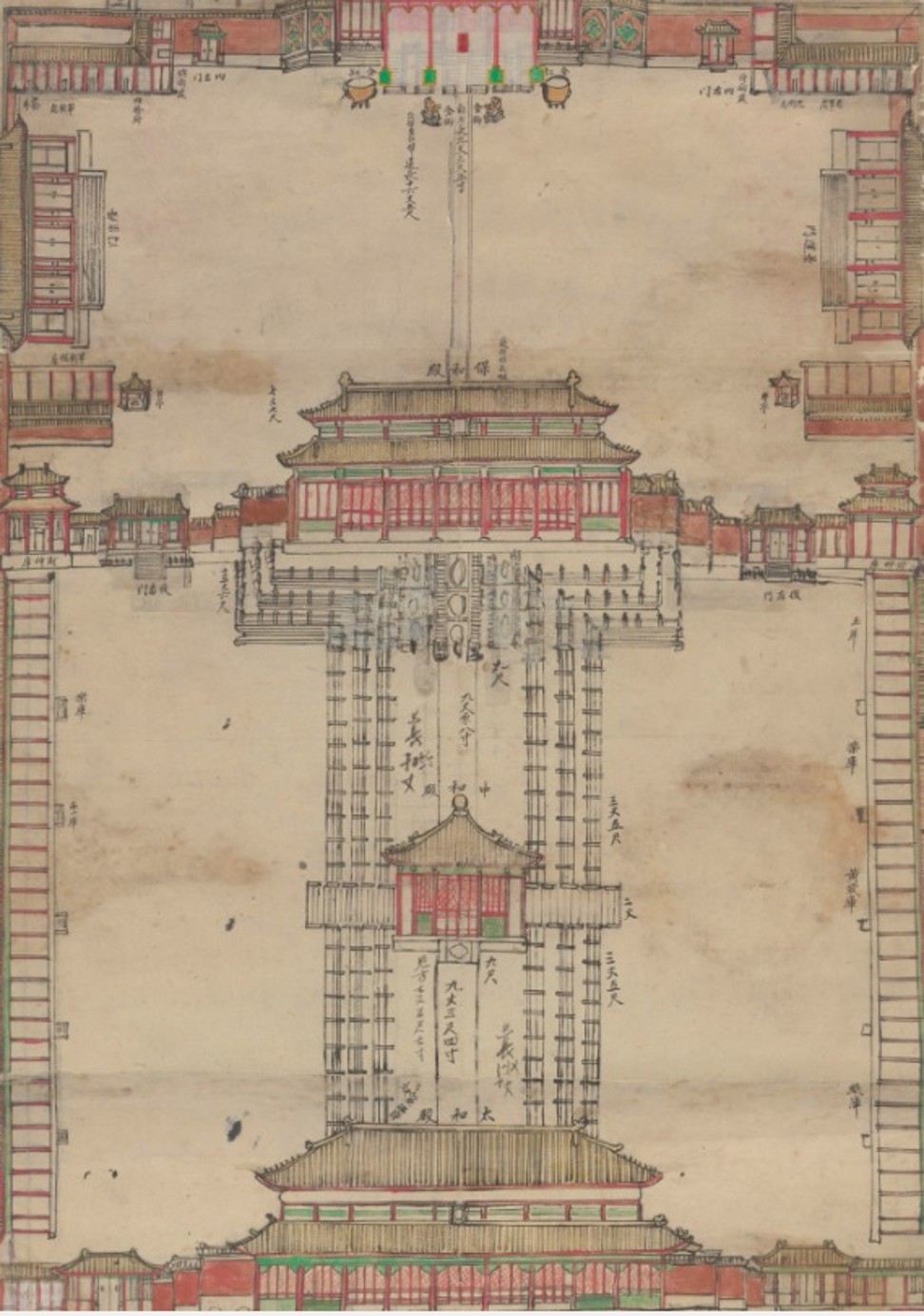

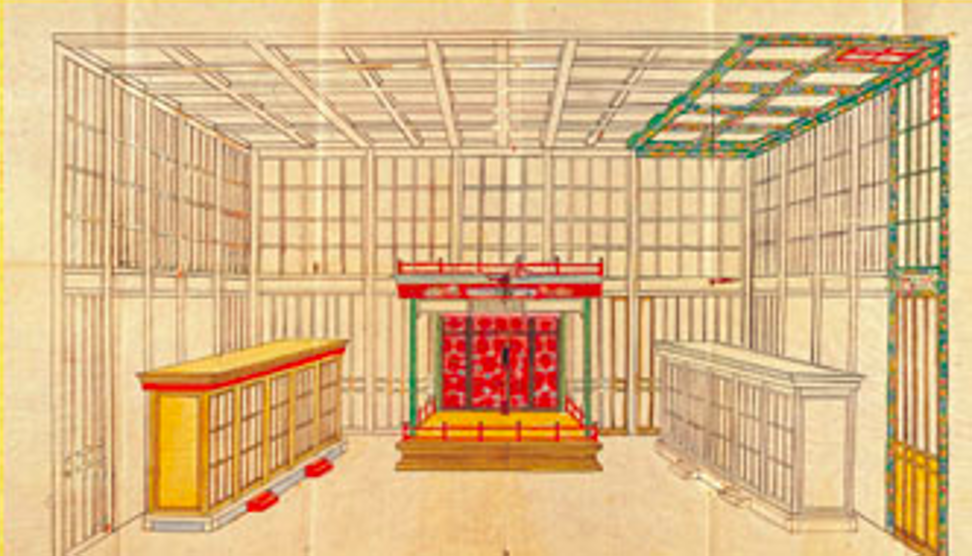

3. Sophisticated detailed ‘preview’ models made for emperors

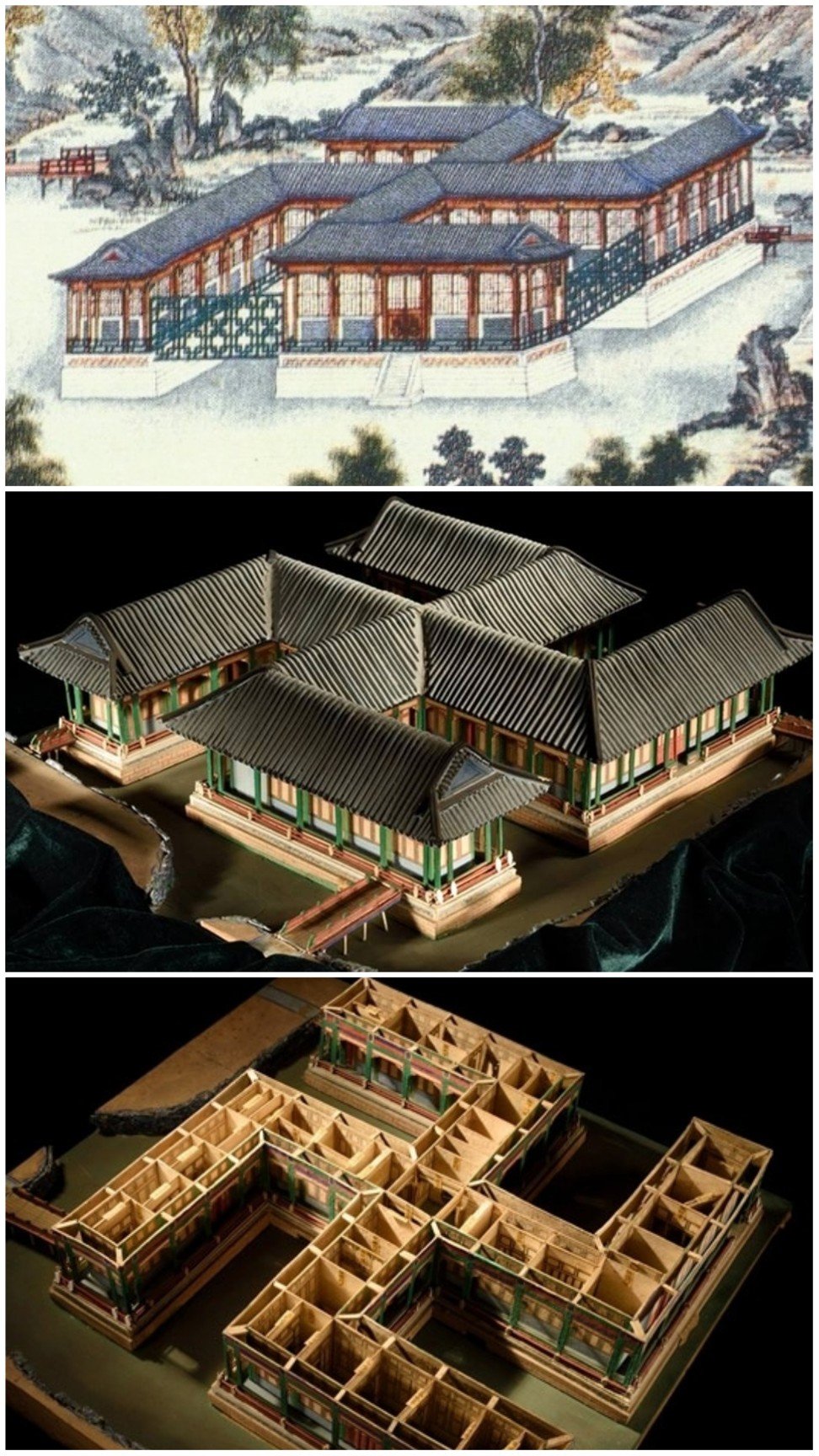

The eight generations of the Lei family helped to gain the trust of emperors as skilful and reliable artisans by making precise drawings and models of their work.

This helped minimise mistakes in the design and construction process and helped the emperors visualise how the finished buildings would look.

In additional to colourful sketches, the Lei architects produced “iron models” out of paper, wood and also small pieces iron pieces – hence the name – which allowed them to create different three-dimensional versions of the buildings.

Precise detailed models, made to a scale of 1/100 or 1/200, were presented to the emperors so that they could see how the work would like once it was finished.

What made these models special was that all of the components could be disassembled.

The emperor could lift off the roof of a model and see the beam structure and decorations of the building. Labels giving the dimensions of the parts of building were also attached.

4. Yuanmingyuan destroyed during Second Opium War

The Yangshi Lei style became widely known during the fourth generation of the Lei family during the reign of Emperor Qianlong, who ruled from October 1735 to February 1796.

The three brothers, Lei Jiaxi, Lei Jaiwei and Lei Jiarui, became known in architectural circles as the “iron triangle”.

They were responsible for a host of renowned imperial buildings, such as the “Three Hills and Five gardens”, the Chengde Mountain Resort and the Summer Palace – completed in 1764 – as well as the Chang Mausoleum for Emperor Jiaqing.

However, Lei Jingxiu, the fifth-generation descendent of the Lei family, was not lucky enough to catch the tail end of the Qing dynasty’s golden era.

He lived between the reigns of Emperor Daoguang, – from October 1820 to February 1850 – and Emperor Xianfeng – from March 1850 to August 1861 – when the nation faced domestic troubles and foreign invasion.

In 1860, during the Second Opium War, the Anglo-French expedition to China pillage and set fire to Yuanmingyuan, the Old Summer Palace, known as the “Garden of Gardens”, in the outskirts of Beijing.

The massive blaze lasted for three days and totally destroyed the palace.

Jingxiu was devastated to see the destruction of the palace, which his ancestors had painstakingly constructed over generations.

However, he was able to transfer all the designs and models to his home during the looting, so that they could be passed on to future generations.

In 2007, Unesco added the Yangshi Lei Archives to its Memory of the World Register.

The documents, including architectural planning engineering and design principles, date from the middle of the 18th century to the beginning of the 20th century and cover imperial architecture in Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Liaoning and Shanxi.

The drawings and models include architectural surveys, design and plans for construction and decoration and refer to cities, palaces, gardens, altars, mausoleums, official residences, modern factories and schools.

Unesco noted that the Yangshi Lei Archives “is not only a treasure trove of Qing-era architectural knowledge, but Qing-era cultural knowledge as well”.

Today, these drawings, models and documents – handed down by the Lei family – can be found at various institutions, including the National Library of China, the First Historical Archives of China, and the Palace Museum and the School of Architecture at Tsinghua University.

5. Lei’s family’s work ended by revolution of 1911

After more than a century of Western humiliation and harassment, the Qing dynasty collapsed in the early 1900s.

In 1900, the Allied forces invaded Beijing and caused serious damage to imperial buildings located both inside and outside the capital.

Eleven years later, the Revolution of 1911 put an end to the monarchy in China and also led to the further destruction of many imperial buildings.

It also brought to an end the Lei family’s traditional position as architects and the skills and craftsmanship that eight generations had passed on to those that followed.

However, the sophisticated buildings that survived the revolution – and the dedication and meticulous work ethic shown the generations of Lei-family architects – live on as priceless symbols of China’s rich architectural history.

Want more stories like this? Sign up here. Follow STYLE on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter

We take a look at the work of eight generations of the family who built lavish buildings – some of which survived 1911 revolution that ended Qing dynasty