Opinion / Is an Apple Watch really better than a Swiss timepiece? Heritage watchmakers like Rolex, Audemars Piguet and Patek Philippe need to innovate quick – or risk extinction

This article is part of Style’s Luxury Column.

If one thing is for certain, it is that things change all the time. In nature, when ecosystems change permanently, species that adapt best not only survive, but actually thrive. Those who try to resist the change disappear, especially when the change is significant and abrupt.

Nature is brutal in its survival of the fittest and so are markets. When consumers don’t find what they are looking for, they will look somewhere else. When you look back, you see past market leaders who lost their relevance by resisting change instead of leading it. In almost all categories, the leaders of the past are not the leaders of the future. Worse, in many cases, past leaders disappear or shrink to occupy a small niche, unable to find broad market appeal. Even countries that defined industries find themselves sidelined if they stop innovating and become unable to adapt to shifting consumer expectations.

The list of brands and categories that went through disruption and lost their past influential position reads like a who’s who of business: IBM, Compaq, Kodak, Nokia, Motorola and BlackBerry are some of the more recent examples of category-defining brands that have entirely or almost entirely disappeared from the categories they once led. More worrisome, in most cases their leaders believed that consumers would always choose them. Remember how BlackBerry insisted people would always want a physical keyboard to write messages? Retrospectively, it sounds absurd.

What we can learn from these examples is that once a brand tumbles, it almost never recovers. Consumers don’t like brands that lose their position as market maker. Once the intangible value is gone, it’s hard to ever get it back. In this aspect, luxury has the highest stakes, as the intangible value gained through ALV (Added Luxury Value) always exceeds all other value components by far. And the nature of intangible value is that it is unstable and can disappear in no time.

Another learning is that no brand or category is safe from obsolescence. I hear time and time again that a certain category is the exception, especially from managers responsible for brands within the category. Consumer loyalty is regularly overestimated. Whenever you hear, “customers will always want this,” it’s a warning. Because everything changes, all the time, and often faster than brands expect or realise.

In the 1970s and 80s the Swiss watch industry saw such a change. Quartz watches by Japanese brands like Seiko, Citizen and Casio replaced mechanical watches on the wrists of people around the world. It was a time when innovation in the forms of higher precision, new form factors and enhanced displays excited consumers and led to a crisis in traditional, rather functional Swiss watch making.

As a result of this revolution the number of Swiss watch markers fell by almost two thirds from 1,600 in 1970 to around 600 just a decade later. If it was not for the launch of the Swatch brand, that became a global major market maker and trend setter, we may not have any Swiss watch brands left today. Nicolas Hayek was the strategic genius behind this move. He realised that without disrupting the whole business approach, the days of Swiss watch makers might have been over. This should be a warning for today’s managers. Swatch shook up the traditional Swiss approach to watchmaking, introduced fun and experience, and produced a brand that created hype and relevance.

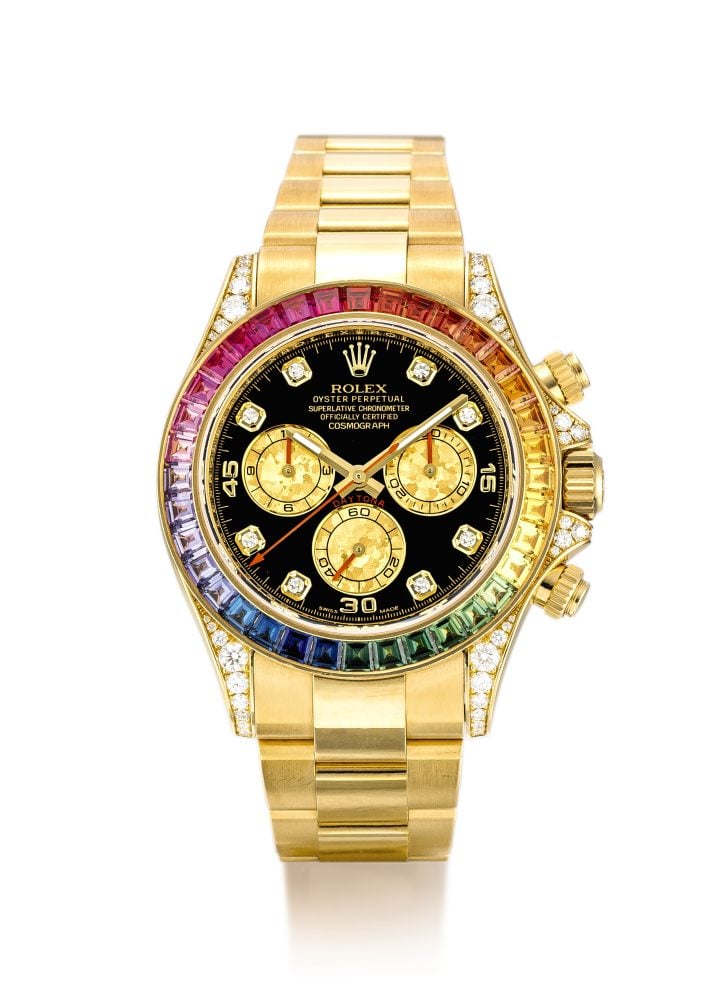

This playbook may now come to an end unless brands find ways to disrupt their own approach again, as they did in the 80s and 90s. Millennials and Gen Z are already voting with their wallets: in just six years, Apple became the biggest watchmaker in the world, completely changing the dynamics of the industry and exposing some of their biggest shortcomings – a traditional retail experience that is often underwhelming, nontransparent (think discounts!) and with little differentiation.

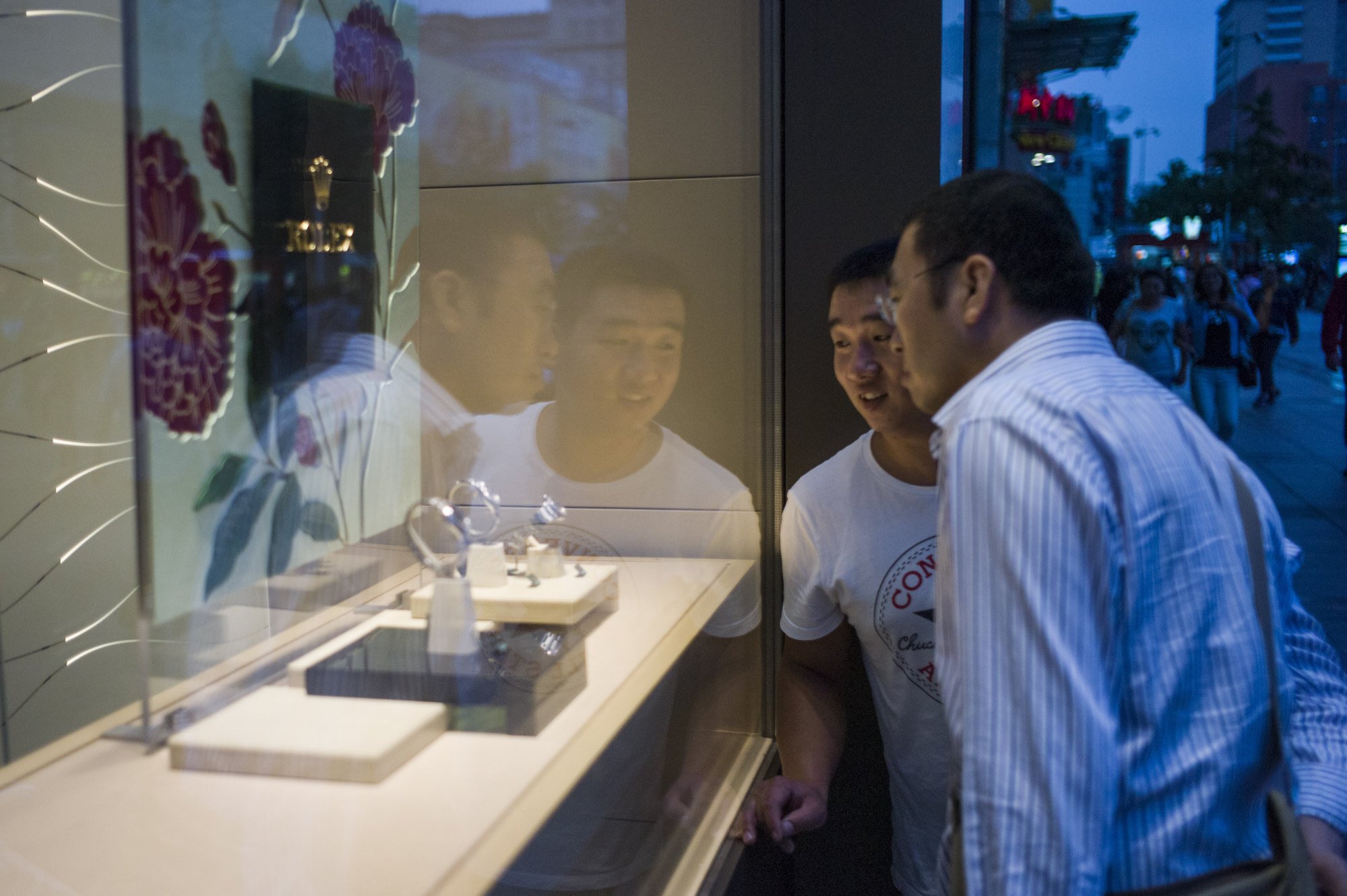

Most brands are sold in a multi-brand environment. Most brand stories simply make history and craftsmanship their key differentiators. But if everyone sells history and craftsmanship, there is zero differentiation from a consumer’s perspective. Even most advertising approaches are basically the same, banking on celebrities and KOLs. As products and stories get more similar, even at a high level of quality, consumers can hardly distinguish the reason to buy a specific brand. What should be an emotional choice, becomes an almost random decision.

The retail model also led to one of the worst customer interactions of any industry. The sales model feels extremely transactional, in many cases, and most brands don’t build long-term relationships with their clients apart from sending them newsletters. There is very little interaction and personal follow-up. Hence, fortunes are spent in advertising to get one transaction and there the connection with the consumer ends. When I recently asked owners of several Swiss luxury watches how often the brands communicated with them since the purchase, the answer was never. Not once. This is alarming. Even embarrassing. A customer interaction model that has no future.

The vast majority of people won’t wear two watches. The likelihood of starting with an Apple as your first watch instead of a Swiss luxury timepiece is much higher. And I see more and more company CEOs and wealthy people replacing their fine watches with the Apple. This is an indicator that the traditional watch industry can’t continue in the same direction. The year 2020 was the worst since the 1940s in terms of volumes: sales in Europe and North America almost stalled. Just selling fewer, more expensive items won’t paper over the cracks. Radically different thinking will be needed, from digital and retail innovations to customer engagement, new business models, and a connected reality. Disruptive, innovative thinking is needed. The clock is ticking, and for many brands it may be already too late.

- IBM, Kodak, Nokia, Motorola and BlackBerry were all market leaders that all-but disappeared overnight after failing to evolve to meet changing trends

- Japanese quartz watches by Seiko, Citizen and Casio threatened Basel’s mechanical watches in the 80s – only Swatch’s disruptive thinking saved Swiss watchmaking