Sedan chairs vs sedans: one used freely by imperial China’s elite, the other needing a US$89,000 permit for Singapore’s elite to own

- The ruling elite, as well as wealthy aristocrats and commoners, in ancient China would be carried around in sedan chairs, or palanquins, by human bearers

- To carry anyone around in a sedan in Singapore requires buying not just the car but a permit to own one, and at US$89,000, they’re only for the elite

My 20-year-old nephew in Singapore just got his driver’s licence. After paying S$2,400 (US$1,785) in total for lessons and tests, he earned the dubious privilege of driving in a city where the cost of owning a private car is among the highest in the world.

As if that isn’t enough of a deterrent, a COE is valid for only 10 years. The cost of renewing the COE is based on the most recent bidding prices of the same vehicle categories, which, needless to say, costs an arm and a leg.

Then there are other expenses like petrol, parking, taxes, road tolls, car maintenance and insurance.

All these form part of the government’s deliberate strategy to limit the number of cars in a densely populated city state of five million, something that I appreciate whenever I am stuck in one of those soul-crushing traffic jams that are so common in other Southeast Asian cities.

I’ve never been enamoured by the cult of the automobile. To me, a car is just a mechanised vehicle that takes you from one location to another – not a marvellous feat of engineering, not a trophy or marker of material success, and certainly not an extension of my personality or a palpable expression of personal freedom.

If anything, I think driving is stressful and I don’t trust my clumsy self behind the wheel, which is why I’ve never learned how to drive. Far better to let others drive the vehicle, be it a bus, a commuter train, a taxi or ride-hailing car.

In imperial China, ordinary people of limited means would most likely walk if they wished to go somewhere, even if it was a long distance away. For those who could afford them, several options were available for hire if they wanted to travel.

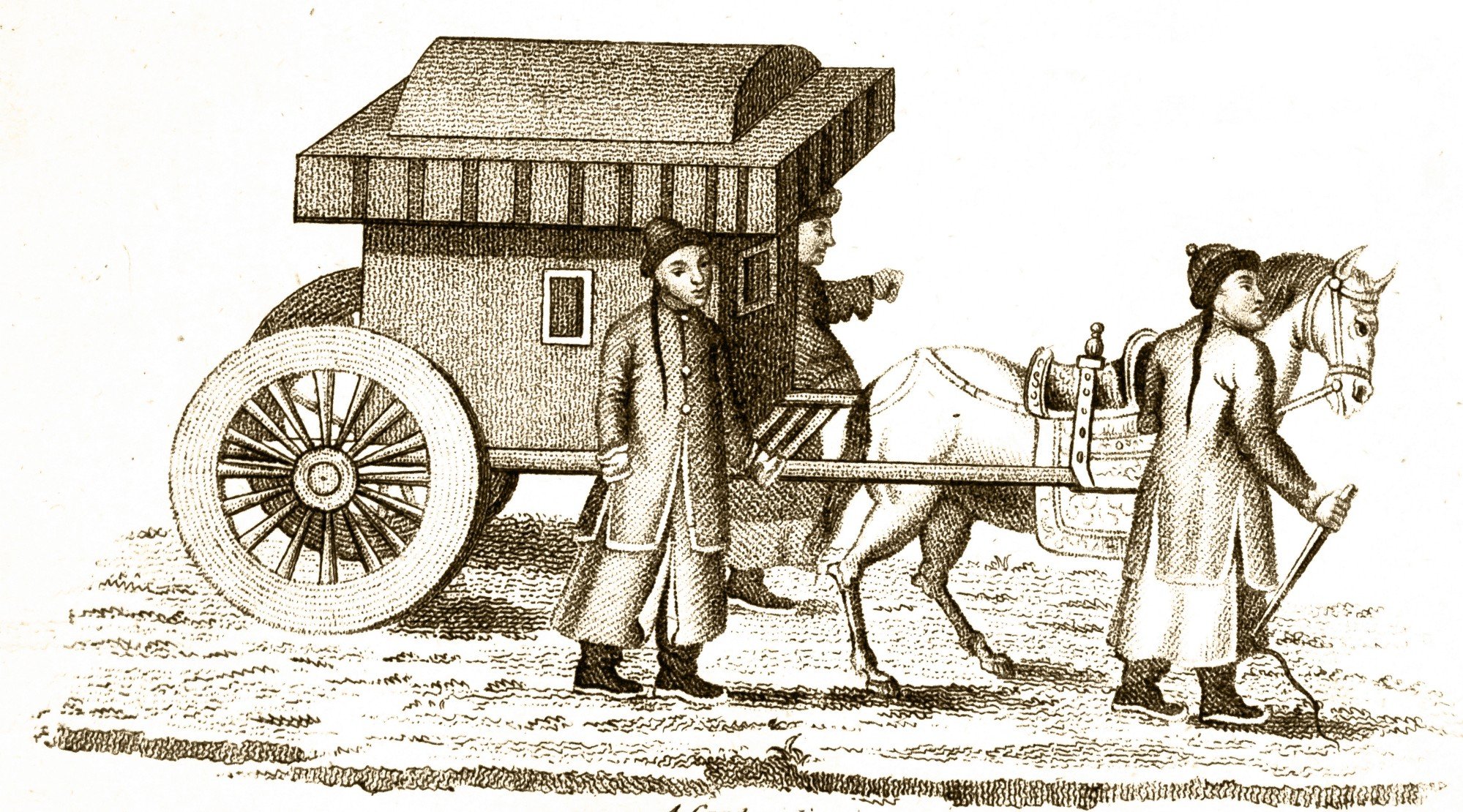

Those who covered long distances usually travelled on covered, wheeled carriages pulled by domesticated animals.

Horse-drawn carriages were faster but the rides were bumpier, while carriages pulled by the slower-paced oxen were much more comfortable. In the cities, donkeys were sometimes used.

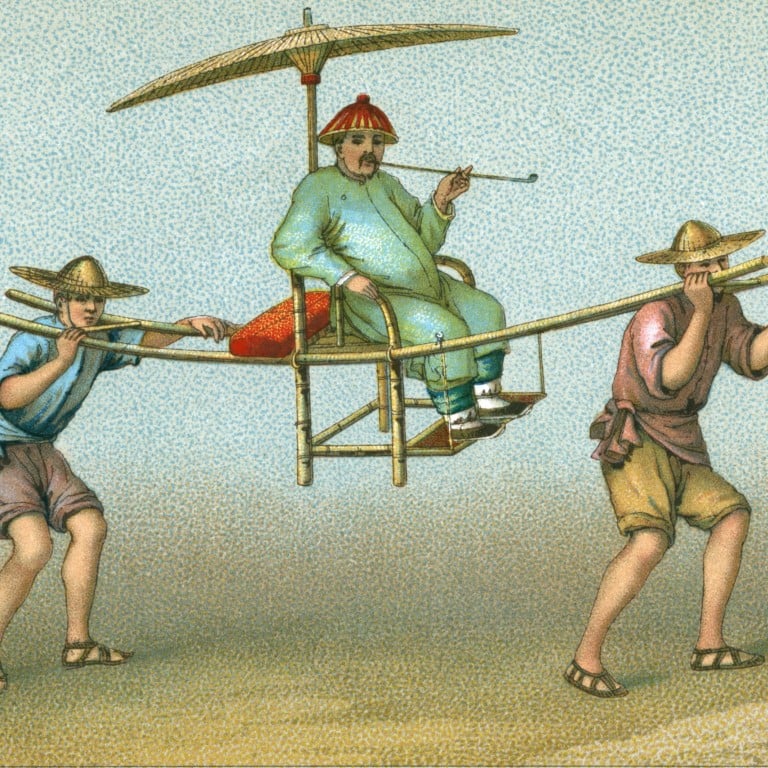

The palanquin, or sedan chair, carried on men’s shoulders in the front and at the back, was also a very popular mode of transport. Its compact size and human bearers made it very manoeuvrable, a useful quality when one had to negotiate tight city alleys or uneven mountain trails.

Members of the ruling elite in imperial China could choose from the above modes of transport in various classes of luxury, shades of colour, sizes of entourage and quantities of trimmings, all of which were strictly regulated according to the user’s rank.

Many of the wealthier aristocrats and officials maintained their own private carriages and palanquins. So did commoners of considerable wealth like farmers with large land holdings, merchants and tradesmen, as well as shady types whose sources of income one would be wise not to inquire too much about.

I’ve been lucky in that my lifestyle doesn’t require owning a car. I don’t have to constantly ferry children or elderly family members anywhere, my work doesn’t require me to be on the go most of the time or at short notice, and I live in cities like Hong Kong and Singapore, where the public transport systems are excellent, inexpensive and safe.