- A writer and filmmaker recounts her great-grandmother’s remarkable journey, from a Shanghai toddler rejecting foot binding to matriarch of a far-flung family

When my great-grandmother Zhang Youyi turned three years old, she experienced a small miracle.

Born in 1900 to a wealthy family in Jiading, a town on the outskirts of Shanghai, Youyi as a toddler somehow managed to make a radical break with the life of her high-born grandmother, mother, aunts and even her own three sisters.

One night around that time, my great-grandmother’s amah had appeared at her bedside. She placed a glutinous rice dumpling in front of the girl and instructed her to eat the entire thing, a rare treat.

The next morning, they soaked her toes and heels in warm water, flexed her tender feet in half, folded her toes into her soles, and bound them with heavy strips of white cotton.

Youyi howled with pain, thrashing about as her mother held her down in a chair. Her screaming might have been fuelled by the horror of realising she would no longer be able to roam freely.

How foot binding was linked to the social status of women in ancient China

Until that moment, Youyi thought that all the things she loved to do – running through the house, playing hide and seek in the garden with her eight brothers, racing down the hutong lanes – were things she would always be able to do.

Despite her weakened state, every night when her mother and amah came to change and tighten her bindings, Youyi struggled and shrieked. The sounds of her distress echoed through her family’s compound so loudly that her second brother, Zhang Junmai, 18 at the time, could no longer take it.

Seeing the despair on her son’s face, their mother relented, pulling the bandages off the girl and carefully unfolding her feet, while Youyi sobbed with relief.

This fortuitous event set the tone for the rest of her life. In turn, her breaking free from tradition would inspire the thousands of women who followed her story, or those who would eventually read her 1996 memoir, Bound Feet & Western Dress.

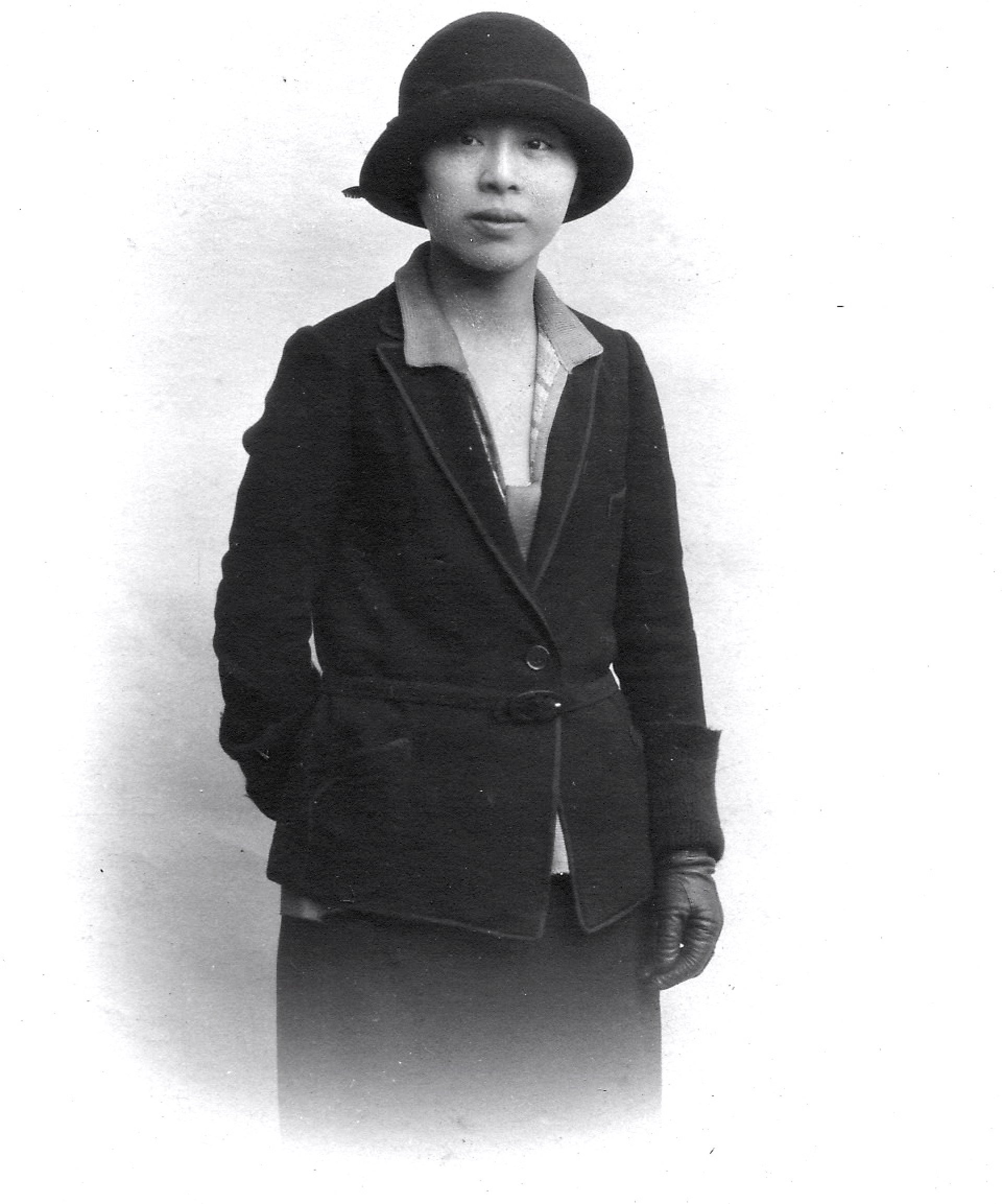

Having escaping her foot-binding, Youyi seemed emboldened, pushing boundaries as a female in a patriarchal society. As a young teen, she somehow convinced her parents to send her to a Chinese boarding school in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, even though during that era it was rare for young women to pursue a higher education.

Eventually, Youyi had to leave her studies, when her parents arranged for her, aged 15, to marry my great-grandfather Xu Zhimo, then 18.

Born into a wealthy industrialist family, Xu would leave China three years later, to pursue an elite education in the United States (including a graduate degree at New York’s Columbia University) and Britain (at the London School of Economics and Cambridge University).

Thus, my great-grandmother first earned status as the wife of a brilliant and accomplished man. But eventually she would also make her own strides as an independent woman.

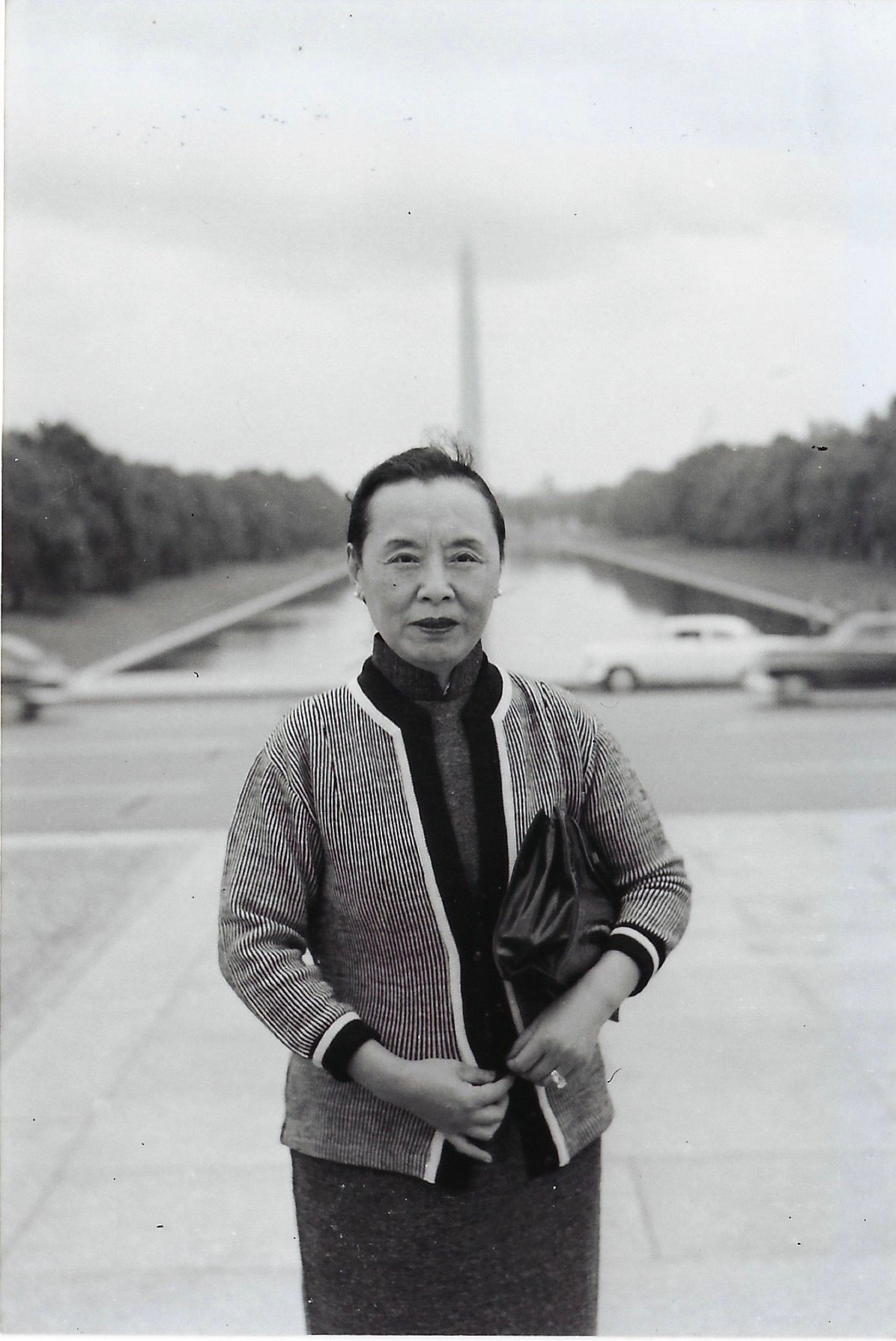

During her 88 years, she achieved what few Chinese women could in the early 20th century – a career and life lived around the globe, all while raising her sons and grandchildren.

My great-grandmother lived in Hong Kong for 26 years and moved to the US to live out the last years of her life, dying a few months before I was born. My father has always said that his grandmother, who doled out sage advice to her grandchildren from thousands of miles away, was his North Star. She became mine, too.

I am always astonished at how much I can learn from an ancestor who I have never actually met.

Dead chat: Chinese man uses AI to ‘resurrect’ late grandma, stirring debate

During her years apart from her husband, Zhang Youyi devoted herself to raising their young son, my grandfather, Xu Jikai. In 1920, two years after Xu’s departure, Zhang, at 20, crossed oceans to reunite with her husband.

Having completed a bachelor’s degree at Clark College and a master’s in political science and economics at Columbia, Xu had left the US to become a research student at King’s College, Cambridge.

Once Zhang had reached British shores, the couple realised they had grown apart, and that they had developed fundamentally different philosophies on life.

When Xu had originally left China, he was determined to learn enough about Western financial structures to return to China and reinvent his homeland’s banking institutions. But once at Cambridge, he soon realised he wanted to be a poet.

His ambitions were to introduce Western metre, rhyme and sensibility to China’s literati and revolutionise literary traditions.

In 1922, Xu demanded a legal separation from my great-grandmother, ultimately securing from her the first Western-style divorce in Chinese history.

Initially, Zhang was devastated; left on her own, barely able to speak English and pregnant with a second child. She moved from Britain to Paris, France, and then on to Berlin, Germany.

It was during that phase of life that my great-grandmother found an inner fortitude. No longer a traditional wife, she rose up, taking full financial care of her small family, all in a foreign country whose language she had just begun to understand.

Looking back on that tumultuous period, she famously declared to her biographer, “I told myself then I would never depend on a man again.” She made good on that promise – her incredible strength and conviction has always inspired me.

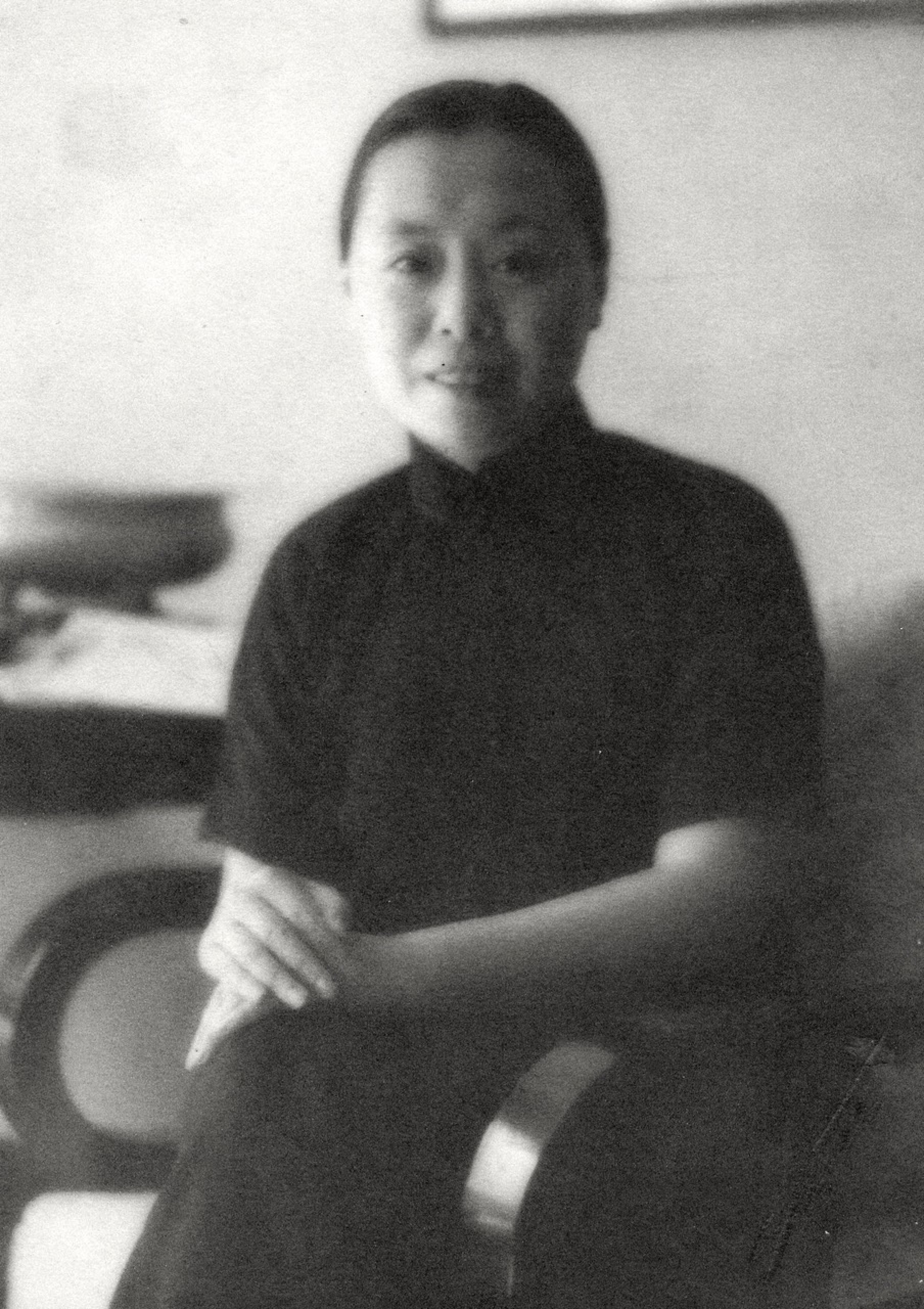

In 1926, having lost three-year-old Peter to sepsis the previous year, Zhang returned to Shanghai, the focus of much scandal as the first Chinese divorcee. Yet she persevered and succeeded in becoming the first female vice-president of the Shanghai Women’s Savings Bank.

During that time, she flourished financially, investing savvily in the stock market, and running a popular upscale clothing business, Clouds & Clothing.

She also built graceful estates for herself and her ex-husband’s parents in the city’s French Concession (even though she and Xu had divorced, she still took her duties as a daughter-in-law seriously), and raised my grandfather on her own.

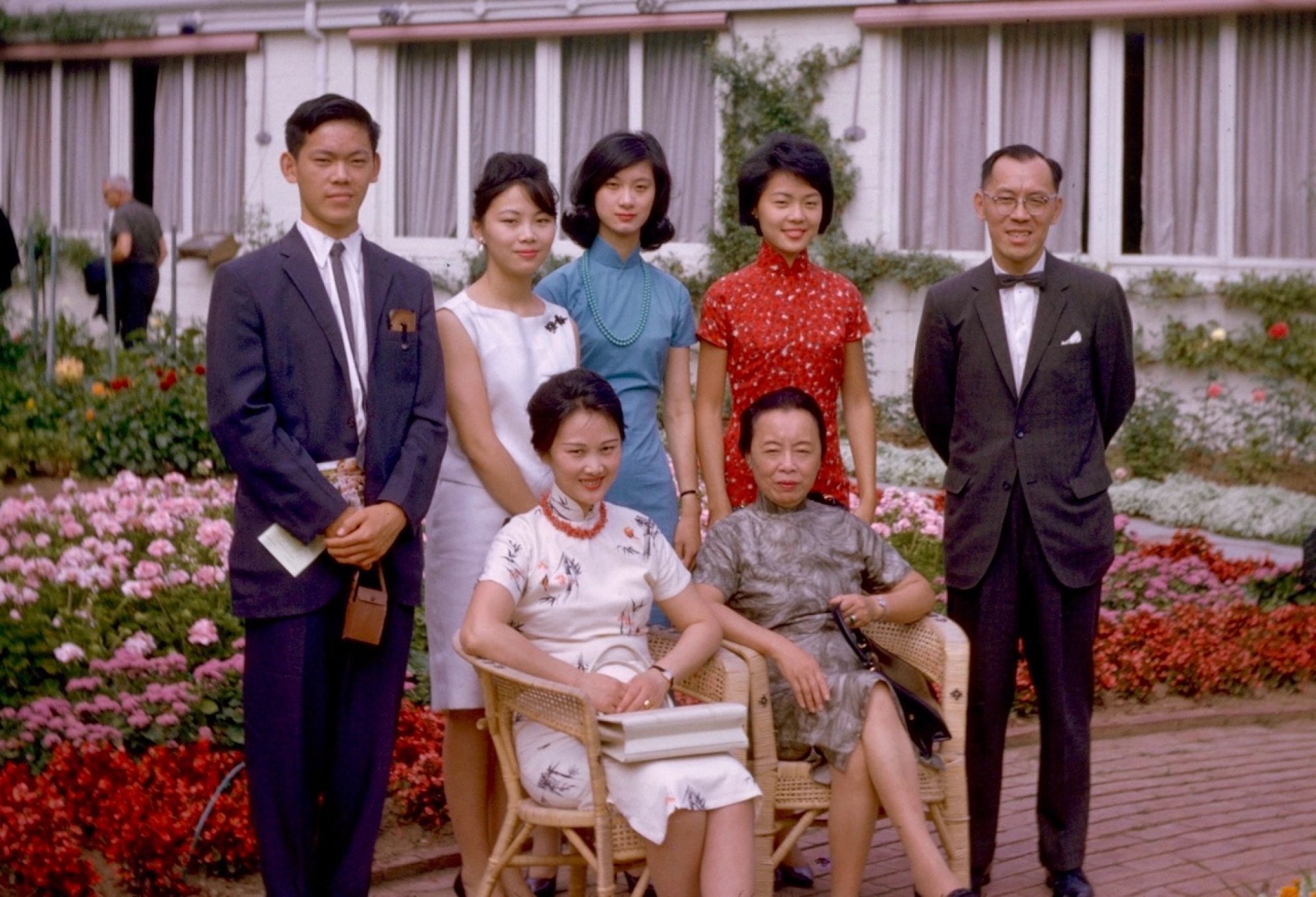

Aged 21, my grandfather Jikai married Julia Chang in Shanghai. By the time they had decided to emigrate to the US for further studies, they’d had four children, Angela, Fern, Margaret and Tony, my father.

The only way the couple could pursue their future in the West was to leave their children in the care of grandmother Zhang.

At the time, my great-grandmother was 48, the age most well-born women of that era were easing into their golden years. And yet she took all four children, her three young granddaughters and my then-toddler father, into her care.

Despite her hard-earned life in Shanghai, Zhang and her young brood were caught in the tumult of history.

At close to 50, she had left her entire life, estate and possessions behind in Shanghai, and faced the daunting prospect of starting over – with four grandchildren in tow.

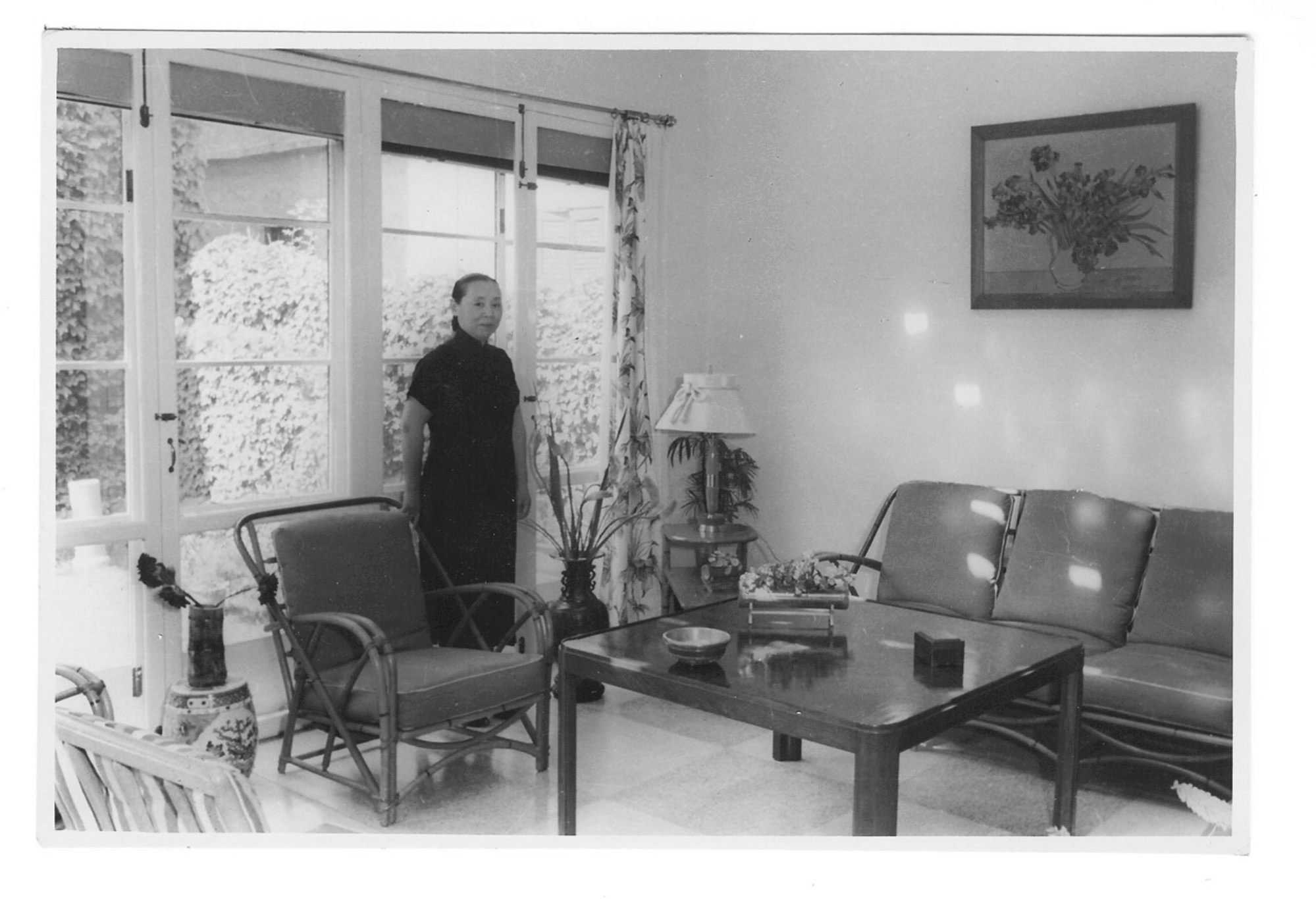

And yet, it was in Hong Kong that Zhang came fully alive. During that era, hundreds of thousands of Chinese were crossing the border in search of a new life.

From 1945 to 1951, the population of the British colony grew from 600,000 to 2.1 million, with Hong Kong’s government tasked with accommodating the new arrivals. In addition, many companies in China moved their operations to the British colony, harnessing the skills and cheap labour of the new immigrants.

Raising my father and his sisters, she established herself as a force for altruism, advising young couples and students on relationship issues, and as a support for thousands of new immigrants. She also found a new love.

After my father and his sisters left Hong Kong for New York in 1952, to reunite with their parents, my great-grandmother married her second husband, Dr Jizhi Su, and became stepmother to four more children. Dr Su’s children were about eight to 10 years older than her grandchildren.

She was constantly stopped by people who wanted to thank her. I was impressed by the number of people who knew of her.Hsu’s father on meeting Zhang in Hong Kong in 1974

My great-grandmother went from caring for four young children to helping to manage a family with four near-adults, each of whom had health challenges.

One of Dr Su’s daughters told my family that while she didn’t appreciate Zhang’s strictness at the time, she later valued how her stepmother brought order to their family, sometimes dramatically turning their lives around for the better.

Hong Kong gave my great-grandmother the opportunity to care for a larger society: children, women and new immigrants. She was a leader in the community and among her friends, a person from whom others sought advice.

In 1974, after my father married my mother, Lily, the newlyweds went to visit my great-grandmother in Hong Kong. My father still remembers walking down the street with her.

“She was constantly stopped by people who wanted to thank her,” he recently told me. “They all felt gratitude for the kind things she had done for charities and for families in need. I was impressed by the number of people who knew of her.”

My great-grandmother’s second act, in Hong Kong, had been to live a life of service to others.

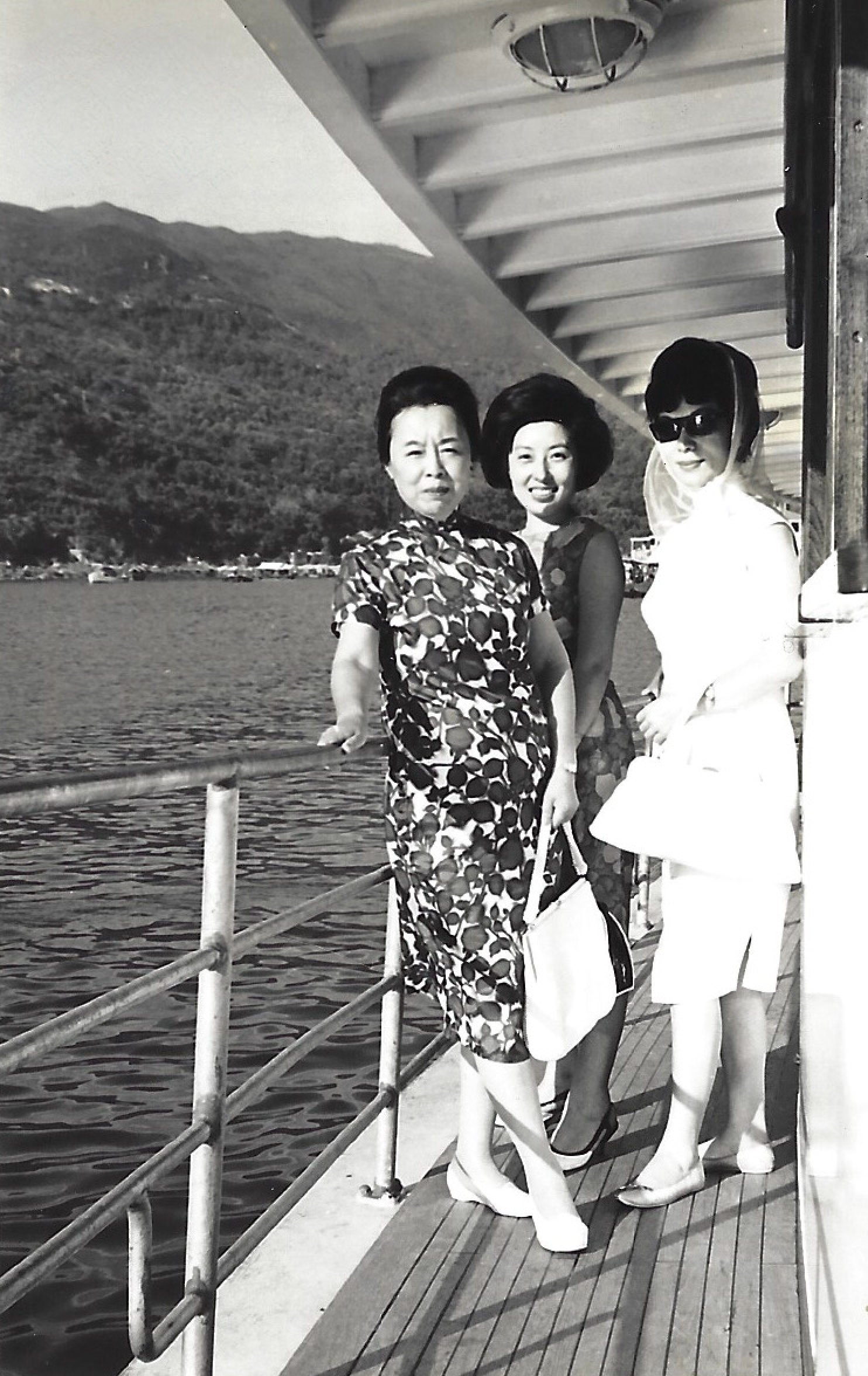

There is a photograph of me, aged two, on the Star Ferry. It echoes a photograph of Zhang on a boat. I can feel a connection between the generations in these images.

There’s something magical about those two photos taken some 30 years apart. Both of us sailing across the harbour.

Po Po is already enjoying a retiree’s simple life of cooking for one and senior tango classes at the community centre. But somehow she knows that Sophie will be her charge for years to come.

Was it a subconscious echo of my great-grandmother’s own story, when she took on the care of her young grandchildren? In many ways, yes.

I got lucky with the casting of Po Po. At a friend’s gathering in Sheung Wan (a traditional Chinese medicine cupping party, actually), I met actress Alannah Ong.

I auditioned her with the young girl my casting agent found to play Sophie, Charlotte Choi Nam-cheung. Ong immediately understood the character I had envisioned: the Shanghai grandmother.

From observations of my Shanghainese grandmothers, mother and aunts, I have found these matriarchs to be bold, strong, determined and sometimes loud. They stand up straight and carry themselves as if they were empresses.

I’m intrigued by the women from mainland China who emigrated to Hong Kong and managed to maintain their stature, attitudes and personality.

The Shanghai grandmother is remarkable for her grace and fortitude, but also for her heart. Ong was both determined and elegant, the same descriptions friends always use for Zhang.

I guess you could say that I came to Hong Kong as a filmmaker to find my great-grandmother.

.png?itok=YVyAvx9C&v=1707970969)