- With the help of a DNA database, the US National Archives, a genealogist and an Instagram post, Ken Hom finally found out the truth about his uncle’s death

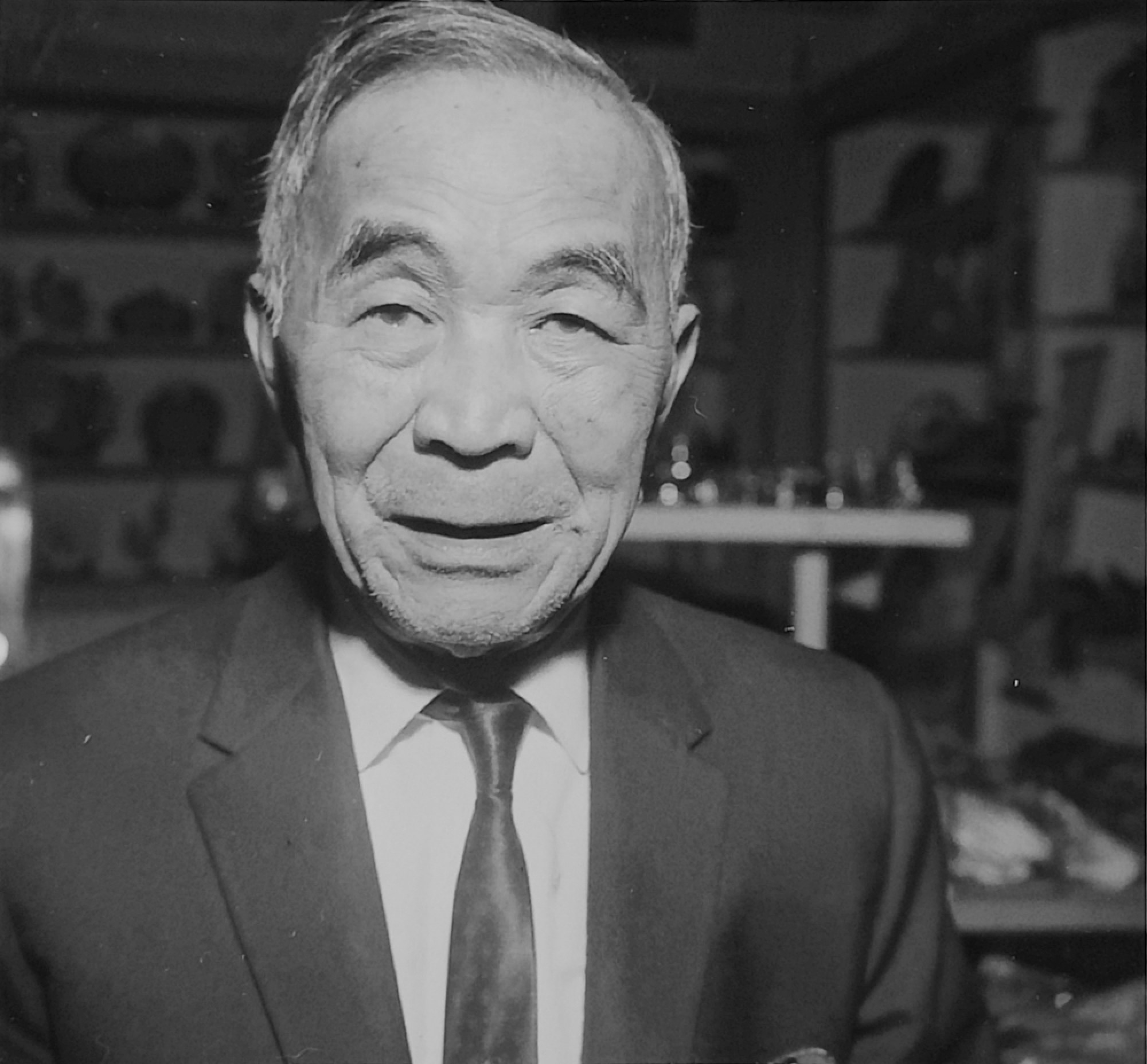

Growing up in Brooklyn, New York, Ken Hom wondered about his uncle, Wing On Hom, preserved in two black-and-white photographs at the family home.

In one, he looks handsome in his army uniform sitting on a stoop. In the other, he is standing, feet together, arms at his sides, in front of a painted scene of a lake with a canoe and wooden cabin.

Whenever Ken’s mother and grandmother lit incense to honour their ancestors and brought out uncle Wing’s picture, or when Ken and his two younger brothers would watch war films such as The Dirty Dozen (1967) or The Longest Day (1962), Ken would ask his parents and grandfather about his father’s older brother.

“Every once in a while we would ask, especially me, ‘Where’s uncle?’ The usual answer was, ‘He went to war and got killed’,” says Ken. “That pretty much shut down the conversation from there. I guess it was a pretty sore subject in the family.”

Ken could sense anger in their voices and felt that something bad had happened but that they didn’t want to talk about it.

“That pretty much was the extent of the conversation about uncle with our family,” he says. “But somehow deep inside of me, I always was just curious.”

All Ken knew was that his uncle was a soldier in World War II and that he was sent to Italy but never came back.

Once, when he pressed his father and grandparents for more details, they told him his uncle had gone to Sicily and died on a battleship.

“It turns out,” says Ken, “this is not true at all.”

Twenty-thousand Chinese-Americans served (the highest number from any minority group and 25 per cent of their total), says the United States’ Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). Private Wing On Hom was assigned to the 7th Infantry Regiment, 3d Infantry Division.

His unit fought against German forces near the Italian town of Cisterna di Latina, about 70km (43 miles) southeast of Rome, and on February 2, 1944, Wing On Hom was declared missing in action – his body had not been recovered and the Germans had not reported him as a prisoner of war.

In September that year, a set of remains was found in the hamlet of Ponte Rotto, almost 5km west of Cisterna di Latina, but did not have any dog tags or other means of identification. All they could surmise was that the soldier had been American.

Four years later, the remains, labelled X-541 Nettuno, were declared unidentifiable and interred at the Sicily-Rome American Cemetery, in Nettuno, near Anzio, Italy.

Though he was born more than a decade after uncle Wing died, Ken never stopped thinking about him.

“I’d been researching on the internet on my own just to see where it led,” says Ken, “and I was kind of satisfied with what I understood from basically whatever was written in the war books and history lessons.”

To pay tribute, in May 2019, Ken posted the photo of his uncle sitting on the stoop in his uniform on Instagram, and five months later he received an email from Marci Bagnulo, a genealogist with Lithic Genealogy, contracted by the US Department of Defense to find living relatives of deceased soldiers from World War II and other conflicts.

In a video call from Roswell, just outside Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States, Bagnulo explains the US Army has a repatriation programme and has set up a DNA database, “so that if remains are found, they’ll be able to identify them through DNA”.

“But, of course, they need living relatives. And my job, and the other genealogists that work for Lithic Genealogy, is to locate living family members.”

The company’s website says there are more than 81,000 unaccounted-for soldiers, airmen and marines, and Bagnulo was randomly assigned Wing On Hom’s file in September 2019 and began, like she does any other search, by inputting his name in ancestry.com.

“They do have a lot of information,” she says, “and I just put in Wing Hom and got 1924 [the year he was born] and his draft record, which said that he lived in Boston, and there was an Ah Wei Hom who was his next of kin [grandfather].”

From there, Bagnulo contacted the National Archives to find the US immigration papers for Ah Wei Hom, which listed his children, one of whom was the father of Wing On Hom. But while there was all this information about Wing On Hom, she couldn’t find his descendants.

How Chinese keyboard apps could potentially expose everything you type

“So I started calling families that had the last name Hom,” she says, “and then almost as a last resort, I googled Wing O. Hom, and the Instagram post popped up, so I emailed him to see. It took us a while to connect but he did respond to my email.”

Bagnulo’s email came out of the blue, and Ken describes her saying, “something to the effect of, ‘We have information that might be of interest to you,’ and at first it sounded like a scam”.

But after a few emails and discussions with his brothers, they decided to speak to her on a three-way conference call.

At first, Bagnulo told them things they already knew about their uncle: that he was born (in China) in 1924 and lived in Boston; had a brother called Wing Horn Hom (their grandfather); and that their grandmother, Wong Shee, lived in China.

But then Bagnulo told them more about their family than any of the brothers had known before.

By using publicly available material from the US National Archives, ship manifests and newspaper articles, Bagnulo filled out parts of the family tree, all the way back to when Wing On Hom’s grandfather, Ah Wei Hom, was born in San Francisco, in 1878, then went to Hoiping (Kaiping), in Guangdong province, got married and returned to the US in 1916.

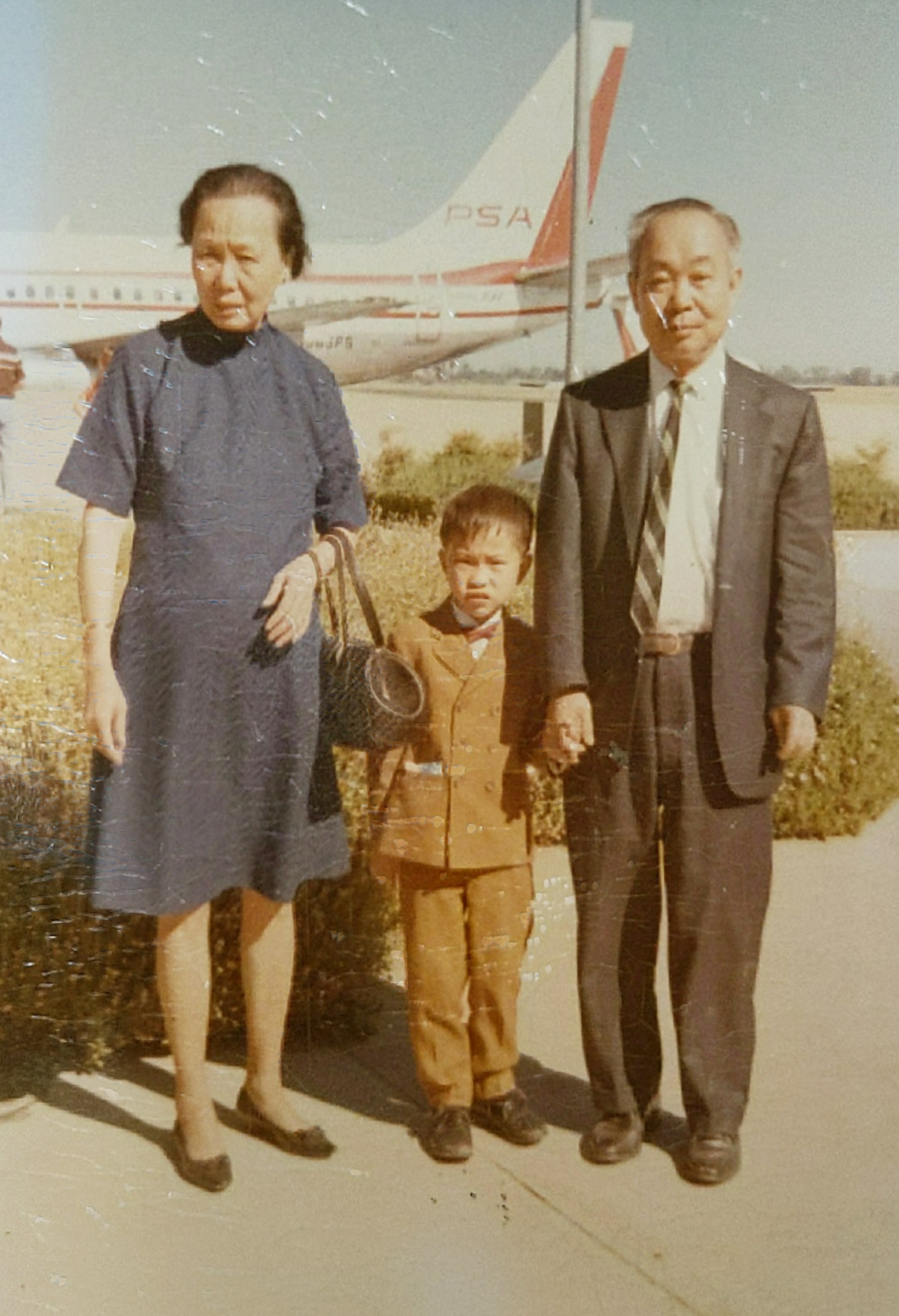

Ken and his brothers had no idea their ancestor had been in America before their grandfather, Wing Horn Hom, in 1926.

“As I told Ken,” says Bagnulo, “‘Your family has been here longer than my family.’ My Italian family didn’t come until 1910, 1920.”

Ken sounds almost incredulous: “She told me the trail of trying to track us got cold and she would not have gone any further if she had not seen that Instagram post.”

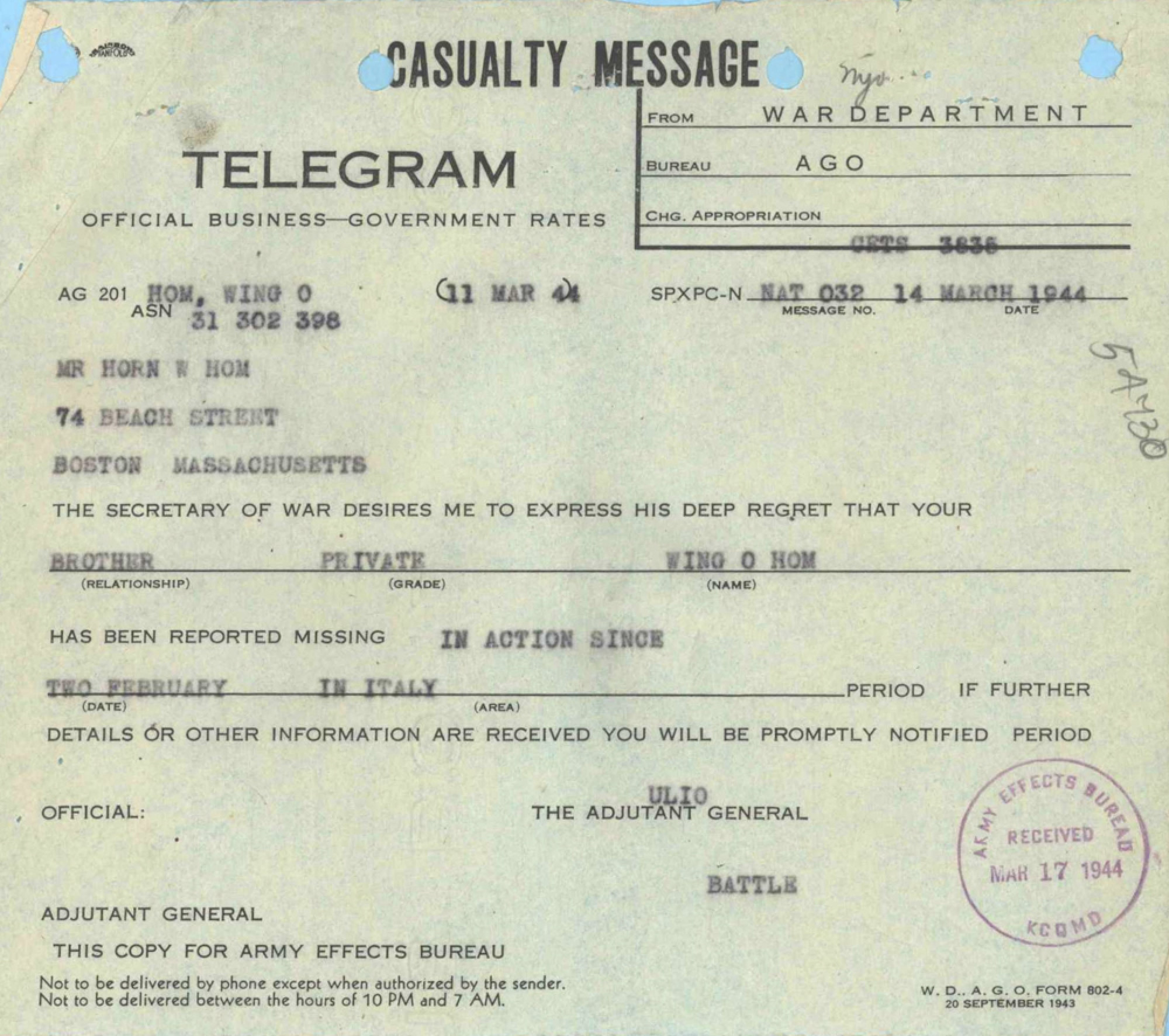

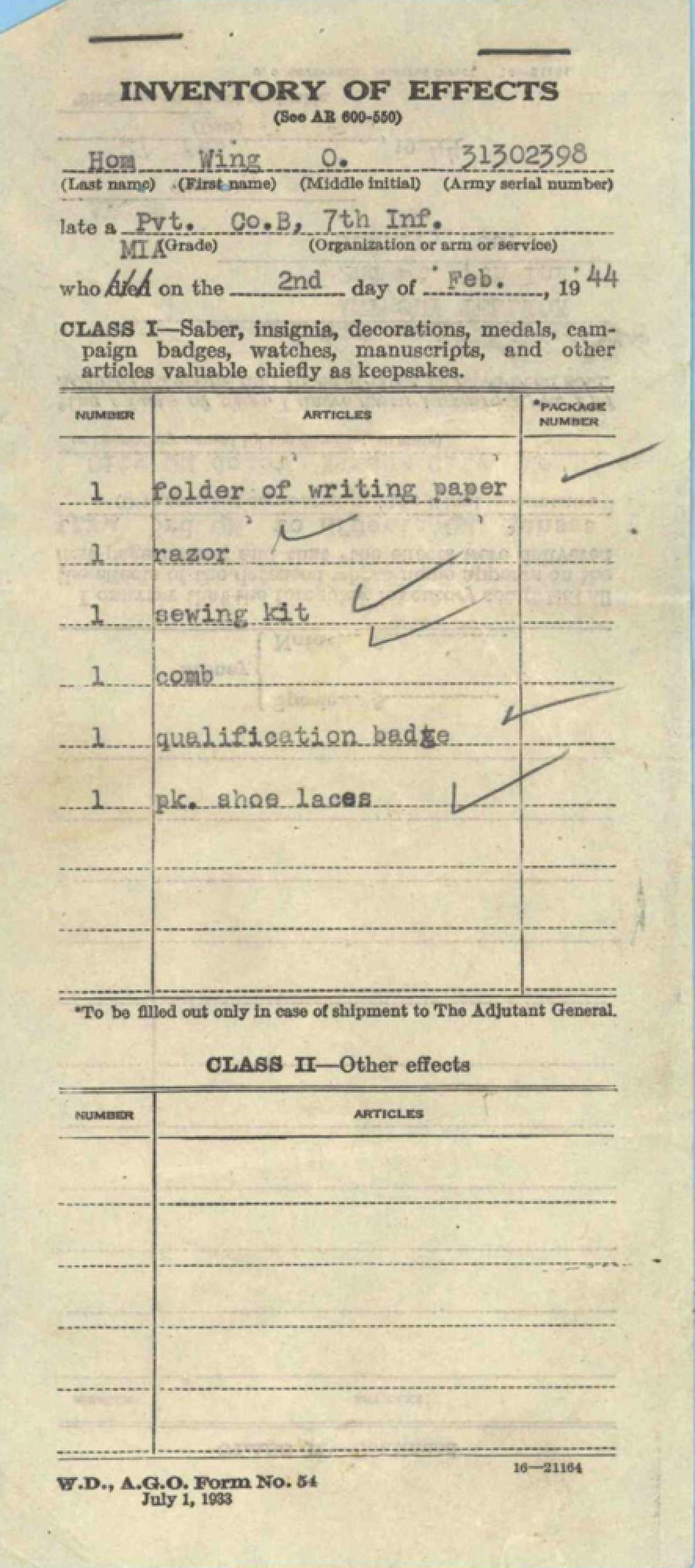

Bagnulo later sent Ken his uncle’s declassified file, containing a list of items found of his, including writing paper, a razor and a packet of shoe laces.

Bagnulo also included a telegram sent to the family about Wing On Hom being reported missing in action in Italy, as well as the family tree Bagnulo had filled out.

“I just flipped out. It was like. ‘Wow this is insane’,” laughs Ken. “It’s amazing what the government has.”

It was also emotional for Bagnulo, but this was her job. Making contact with the Hom family meant she had completed her task.

She wrote a report that included the Hom family’s contact details to her superior at Lithic Genealogy and from there the information was passed to a mortuary affairs officer with the past conflict repatriation branch of the US Army. (Despite repeated requests, the mortuary affairs officer was not available for comment, nor was any representative from the DPAA.)

Ken’s father, Kwong Suey Hom, died in March 2019, unaware the US Army was still trying to find his brother Wing On Hom all these decades later.

In December 2019, Ken was contacted again to provide a DNA sample and he enthusiastically agreed, along with his brother Danny. Their father’s sister, Shiu Yin Yee, is in her 90s, has dementia and lives in California, but her son helped get a DNA sample from her as well.

Then the family waited, cautiously optimistic the remains might be a match.

My new-found appreciation for my uncle is because he came into a country where our people weren’t wanted, and to enlist was even more unfathomableKen Hom

The Sino-Japanese war that broke out in 1937 had prompted Wing On Hom and his younger brother, Kwong Suey Hom, to leave China.

In 1939, aged 15 and 14, respectively, the two teenagers, who didn’t know a word of English, left Hoiping by ship and arrived in Seattle, Washington, before making their way to Boston to meet their grandfather.

The Immigration Act of 1924, which discriminated against Chinese coming into the US, had been enacted by then but the pair were allowed in because their grandfather had sponsored them. However, each had to pay the head tax.

Despite the racism he experienced after he arrived, Wing On Hom demonstrated his patriotism for his new home by enlisting in the US Army when he was 18 years old. It was not long after this that he and his unit were sent to Italy to fight with the Allies.

On January 30, 1944, Wing On Hom’s unit was dispatched to secure a point in Cisterna di Latina, but when they got there, it was already occupied and they were ambushed by the Germans.

‘The first Chinese chief in Africa’, but does he wield any real influence?

By February 2, Wing On Hom was declared missing in action, at the age of 20, and his family didn’t know what had happened to him except that he was officially declared dead a year later.

“When I was a child, I would always see my grandma or mom pull out uncle’s picture when they did bai saan [honouring ancestors with incense and offerings],” says Ken, “and I kind of knew there was much more to uncle than just being a soldier.

“It was a story that was never told nor did they have any more knowledge of him than what my brothers and I already knew.”

In September 2021, the remains of X-541 Nettuno were disinterred and sent to the DPAA laboratory in Nebraska. From the coordinates of where the remains were found, and taking into account other casualties, it was believed the remains could be those of Wing On Hom.

Children? No thanks – pets and partying are the future in China’s new normal

By this point, the remains were mere bone fragments. Professor Sophie Sneddon, a lecturer in genome forensics at the Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, Canada, explains it is hard to get quality DNA from bone samples, but there is an alternative method.

“We have another type of DNA in our cells called mitochondrial DNA, which is present at very high copy numbers in each cell and is not part of the chromosomes,” Sneddon says by email.

“This type of DNA is inherited maternally, so your mitochondrial genome will be exactly the same as your mother’s and grandmother’s, etc. By comparing the mitochondrial DNA in the bones with that of the sister, you can see if they share the same maternal line.

“This is the only thing you can conclude from results such as this, though, because they could be related anywhere along the maternal line, not just brother and sister.”

She says the DNA taken from Ken and his brother Danny was used for Y-DNA testing, which she explains is “inherited paternally, so a male will share the same Y-DNA markers with his father, grandfather and so on.

“By using these samples in addition to the mitochondrial DNA samples from the sister, it would have given confirmation that the remains belong to a specific person.

“If you used just mitochondrial or Y-DNA information alone, you’d only have information on the maternal or paternal lineage. As this information will change with every generation, it makes it easier to be sure that you have accurately identified the remains when you look at both together.”

On April 19 this year, Ken was contacted by the DPAA and finally informed the skeletal remains had been positively identified as those of his uncle Wing On Hom.

“All these years of remembering, asking my dad and talking to my dad about it, my grandpa …” says Ken. “All that just flashed through my head, and hearing that they’ve got a match? It was just unreal […] I never knew they kept such detailed records.

“My new-found appreciation for my uncle is because he came into a country where our people weren’t wanted, and to enlist was even more unfathomable.”

Ken says his father tried to enlist, too, but was rejected because of his flat feet, the belief being that people with this condition were not of good health or would not be able to withstand long marches.

How China became the dominant force in world chess – with help from Asia

The US Army asked Ken and his family if they wanted Wing On Hom to be buried in Arlington National Cemetery, in Virginia, or in a cemetery of their choice.

Ken felt that it was “our duty to have our uncle buried along with his parents for his and his parents’ circle to be complete”.

On October 11, a funeral was held for Private Wing O. Hom at the Evergreens Cemetery in Brooklyn, near the graves of his younger brother and his parents.

The Chinese American Citizens Alliance, which fights against discrimination and honours Chinese-American soldiers, held a ceremony alongside the US Army, which conducted its colour guard formalities, where four cadets paid tribute to the fallen soldier.

For both his heroic service and dying in the field, Wing On Hom was posthumously awarded the Bronze Star and Purple Heart medals by the US military, having finally been laid to rest on home soil, eight decades after his death.