- A 50th anniversary reprint of a 1969 guidebook, Taipei After Dark, that described a seamy side to the city in the Vietnam war era prompts some fact-checking

In 2019, posts began popping up on my social media about a retro oddity, a 1969 guidebook called Taipei After Dark, which had just been published in a 50th anniversary edition.

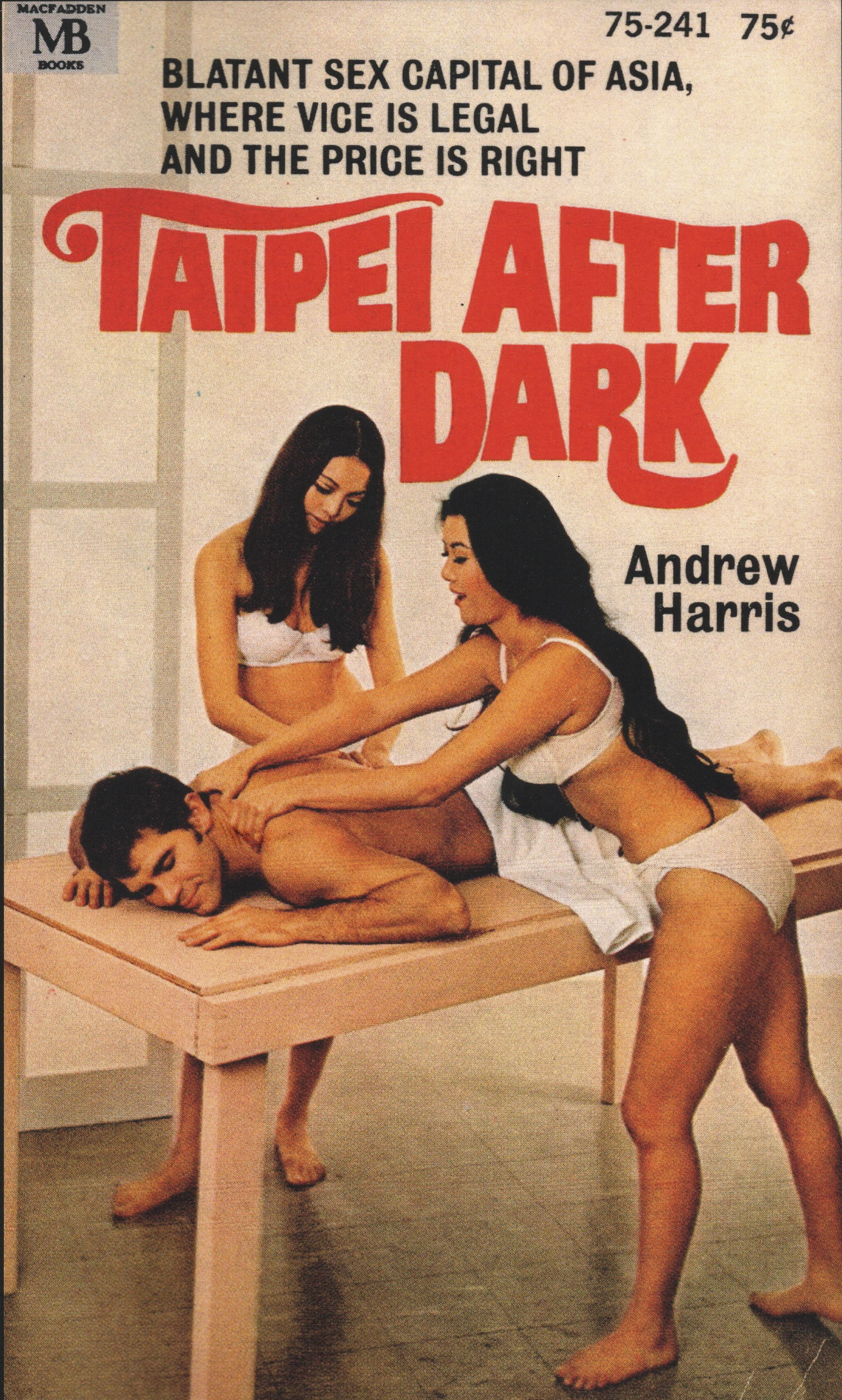

The book’s cover depicts a Western man being massaged by two Asian women in bras and panties, below a title in a groovy comic-book font.

It has the kind of sensational camp of an early James Bond film, but with a subheading that declares Taipei to be the “blatant sex capital of Asia, where vice is legal and the price is right”.

“If you are in Tokyo or Manila or Bangkok,” the introduction reads, “and announce that you plan a trip to Taipei, the reaction is always the same. You will be met with lascivious leers and exclamations of envy, for in recent years Taipei […] has won the reputation among old Asia hands of being the most blatantly sex-oriented capital of the East.”

The book is obviously fantastical, but it also begs the question: how much, if any of this, could possibly be true?

Taiwan as an island of brothels is certainly a far cry from the island’s squeaky clean image of microchips and boba tea. But as I began to pick and poke my way through the book and the story of how it came to be, it turned out that it held much more of a historical record than one might initially assume.

The Hong Kong drag group keeping things raw – forget RuPaul’s Drag Race

The guide had originally been part of a pulp travel series of After Dark titles covering world cities, which in Asia included Saigon, Bombay, Tokyo, Hong Kong and Manila.

They were slim pocket books of 100 to 150 pages, their covers barely the size of an index card, and they were sold cheaply in revolving wire stands at airports and chemists.

As the original publisher, a British house called Macfadden Books, was long defunct, having been folded into multiple mergers, the republication was somewhat mysterious. The new edition was by an outfit called Bullocks Publishing, which was not only untraceable but obviously having a laugh.

The rest of the guide’s 100 pages include a strange brew of not only racy first-person sexual scenarios, but the kind of political overviews you might find in a country report by the Economist Intelligence Unit.

I think you can say that I was attempting to save a snapshot of history’s dark sideWendell Minnick, who republished Taipei After Dark

There were any number of canny observations, such as that in the 1960s, Chiang Kai-shek’s American supporters were a motley bunch of “discredited racist Southern senators […] new-McCarthyite ex-FBI agents […] and small-time radio station owners and publishers”, all of whom were received in Taipei as “distinguished free world statesmen” as long as “their views are sufficiently to the right”.

The sexual scenarios manage to be both regressive and progressive at the same time. While it is impossible to defend the book’s basic premise of sampling prostitutes on a business trip, the guide also presents a sense of equal opportunity in sections on gigolo services for women and a luxurious underground of gay and lesbian scenes.

In short, it is a vision of 1960s Western sexual liberation in the context of atavistic Asian patriarchy.

But it is in the details that things get interesting. Every bar, club and hotel mentioned – including the Suzie Wong, Little Woman Bar, the Friends of China Club and the King’s Club – can be verified by contemporaneous bar guides published by the United States military.

The guide’s author, Andrew Harris, was in 2020 revealed by Taiwan-based writer and historian John Ross to be the nom de plume of Frederick King Poole, a roving freelance journalist who hopped in and out of the war zones of Indochina and wrote at least 10 Asia travel guides during the 1960s and 70s.

These included conventional guides for almost every country in Southeast Asia, all authored under his real name, while as Andrew Harris, he penned Macfadden sex guides to Taipei, Bangkok and Manila.

It’s amazing how few Cold War-era novels were set in TaiwanJohn Ross Grant, in Taiwan in 100 Books

In Poole’s 2015 memoir, The Aqua Mustang, he lets slip terse memories of sampling prostitutes throughout the Far East, listing off “the surprisingly fresh and syrupy night girls of Djakarta, the Bangkok girls who gave full body massage with their bodies, the slippery sweet bath house girls outside Taipei, or that girl who filled her mouth with crushed ice in Manila”.

He also admits that, as a commercial writer, he had experience in burnishing the truth.

“I did know how to lie and embellish and play the travel writing game,” he wrote. “I had done it when broke in Asia.”

But he also relates that the Taipei guide was based on his own research – “even in the middle of the night” – and “mostly based on truth”.

While discussing Taipei After Dark with some historical-minded friends, we discovered that a cartoon bulldog logo on the 2019 edition’s back cover was the same as that used on a blog written by a local, off-the-wall character, a long-time Taiwan defence correspondent named Wendell Minnick.

In Pentagon circles, Minnick has been described as a “gonzo” reporter and is viewed as an oddball who might have sailed too far up some Taiwanese river.

I first met him in Taipei during the late 1990s. Back then he was a beefy, six-foot (1.83-metre) tall, 250-pound (114kg), farm-bred Indiana boy, who in addition to holding an encyclopedic knowledge of Taiwan’s military armaments, scribbled articles on the side for Powerlifting USA magazine.

Before coming to Taiwan, Minnick had almost joined the CIA, entering the agency’s pre-processing programme while still in graduate school at Western Kentucky University.

But after nearly three years of tests and interviews, he recently told me, the realisation hit him: “The agency was a bureaucratic nightmare. So I asked myself, ‘Do I really want to join these nuts’?”

By that time, he was already in talks with a publisher about a directory of espionage. That launched him on the path of a writer, and in 1993 Minnick ended up in Taiwan, where he spent the next couple of decades as a correspondent for Jane’s Defence Weekly and as Asia bureau chief of Defense News.

Over the years, his scoops have included the construction on a Taiwanese mountaintop by the US of a large array of satellite dishes for eavesdropping on mainland China, covert visits to Taiwan by US military and intelligence officials that lead to an US$18 billion arms deal in 2001, and Taiwan’s contracting the private security firm Blackwater to train its presidential security detail.

John le Carré’s time in Hong Kong, and a detail about it that he got wrong

He also has a passion for outing Western defence contractors who sell illegally or through grey channels to the likes of Iran and North Korea.

Two, three and even five decades after the original publication of Taipei After Dark, Minnick still hangs around in the sticky corners of the old military bar zone described in the book, encouraging drunk US officials, some of them on covert visits, to leak stories to him.

I emailed Minnick to ask if he was in fact behind the republication of this 1969 guidebook. He answered cryptically, saying that he inhabits a “very weird world” and telling me he prefers to talk face to face.

We meet in an old bar called the Manila, which looks to have not been redecorated since it first opened in the early 1980s.

Framed pictures are now stained black with cigarette smoke and cracks in the plaster walls are bound together uselessly with cellophane tape. It’s probably a good thing that the lights are too dim to see the fake leather upholstery I’m sitting on.

I ask him if he’s behind the new edition of Taipei After Dark.

“Yes,” he says, “I published it.” Then after some discussion, he finally agrees to let me disclose this in print.

In re-releasing the book, he initially wanted to “play the trickster”, he says, but as a journalist and hardcore advocate of free speech, he also understands I want to tell a true story.

So why, I follow up, did he yank this bit of pulp out of history’s dustbin?

“I think you can say that I was attempting to save a snapshot of history’s dark side,” he says.

In a review of more than 400 years of Western literature on Taiwan, Taiwan in 100 Books (2020), author John Grant Ross observes, “It’s amazing how few Cold War-era novels were set in Taiwan.”

Though the island provided an “embarrassment of riches”, writes Ross, including invasion scenarios, spies, gangsters and Byzantine political entanglements, there are only a few scattered descriptions of what life was like in Cold War Taiwan.

Instead, Western writers mostly viewed the island from the outside. One bestselling example is the 1981 novel Noble House, set in Hong Kong in 1963, in which author James Clavell repeatedly alludes to an always offstage Taipei in one of only three ways: a den of scheming Chinese Nationalists; a place to build a factory; and a kind of splendiferous whorehouse.

Taiwan’s capital, in Clavell’s telling, is home to the “House of Many Pleasures” and the “Happy Hostess Night Club”, establishments that colour the backstories of the main characters, Hong Kong’s expatriate tycoons.

In a recurring theme that spans more than 1,000 pages, he also prepares the novel’s readers to witness a men’s only weekend in Taipei, much to the chagrin of a female executive, who, upon discovering she’s not invited, exclaims in frustration, “I’ve heard it’s a man’s place so if all they’re after’s a dirty weekend it’s fine with me.”

It is one of the more prominent literary images of Cold War Taiwan in any major Western novel, but ultimately, the Taipei weekend never comes to pass.

Clavell wrote his novels with only starting and end points in mind, improvising much of what happened in between. Owing to several plot twists, the Taipei trip is cancelled.

Though Clavell never provides us with a description of Taiwan, he certainly says something about its reputation. It’s a view that can be backed up by fragments of journalistic documentation.

The army really didn’t want wives and girlfriends back home knowing what was going onSyd Goldsmith, who researched Vietnam war era R&R for a 2006 novel set in Taiwan

The December 22, 1967, issue of Time Magazine created a major scandal with the publication of a photo of a US soldier, Corporal Allen Bailey, being bathed by two gorgeous, naked Taiwanese prostitutes in a hot-spring resort in Beitou, just north of Taipei.

The caption reads, “Not every GI is inclined to tear himself away from the pleasures of Taipei […] But those who do […] have never regretted their decision.”

In the photo, Corporal Bailey is pictured with his eyes closed in silent bliss and smiling like a Cheshire cat. (Sadly, he was killed in combat before the photograph was ever published.)

“Chiang Kai-shek’s government was outraged,” recalls Syd Goldsmith, a retired US diplomat, who arrived in Taiwan in early 1968.

Now a hearty, silver-haired 85-year-old and still a regular on Taipei’s public tennis courts, Goldsmith was then in language training in central Taiwan. He would later go on to serve as political officer at the US embassy in Taipei from 1970 to 1974 and then, following the break in US-Taiwan diplomatic relations, as head of the American Institute in Taiwan’s Kaohsiung Branch from 1985 to 1989.

He still lives in Taipei.

“The picture was famous, of course,” he says. “It was censored here. It was clipped out of everything that came through, because that was the practice at that time.”

The government of Nationalist leader Generalissimo Chiang, he recalls, “threw a sort of tirade about how this doesn’t represent us. We don’t do that sort of thing. One of the purposes was to tell the rest of the world that we’re not a whorehouse”.

The photo was part of Time’s Christmas spread on the US army’s rest and relaxation programme for soldiers in Vietnam, which allowed soldiers five days of leave in one of Asia’s major cities.

In Taiwan, R&R brought in nearly 200,000 American soldiers between 1965 and 1972, according to Taiwan government records. This represented a huge influx beyond the roughly 10,000 US troops permanently stationed on Taiwan, of which only 1,000 or 2,000 were in Taipei.

Goldsmith later researched R&R for his own 2006 novel, Jade Phoenix, which was set in Taiwan from the 1950s to the 70s, but outside that lone Time article could find little information on the programme.

“The army really didn’t want wives and girlfriends back home knowing what was going on,” he says. “And they managed to squelch the publicity.”

The introduction of red-light and bar districts throughout Asia during the Cold War is perhaps one of the great under-acknowledged legacies of the US military presence in Asia.

The 1950s produced Roppongi in Tokyo and Itaewon in Seoul, while the Vietnam war gave us Patpong in Bangkok, Angeles City in the Philippines and a Taipei bar district now known as the Combat Zone.

The new Taipei bar zone covered about 3km of Taipei’s major thoroughfare of Zhongshan North Road, a tree-lined, doubly divided boulevard along which all traffic was stopped twice daily for the commute of Chiang..

Before R&R, this road had only a small red-light district at its southern extreme known as “Sin Alley”, in present-day Jingzhou Street. At that time, Taipei had two officially designated red-light districts, Wanhua and Dadaocheng.

Prostitution had, in fact, been legalised in Taiwan by Chiang’s Nationalist government as early as 1949, but its licensed brothels were only for local Taiwanese. American servicemen were kept out by patrolling teams of American Military Police and Taiwanese Foreign Affairs Police.

With the advent of R&R in 1965, Zhongshan North Road transformed into a sprawling, neon-lit strip of girlie bars and cheap hotels, and Taiwan’s population of licensed prostitutes skyrocketed from around 2,000 in 1962 to 23,000 in 1970, according to Taiwan government figures.

There were only a few copies on the internet, and they were selling for US$100 eachWendell Minnick on discovering the existence of Taipei After Dark

When the number is expanded to include illegal sex workers, one estimate by a contemporary scholar put the total at 105,000, or one in 40 Taiwanese women.

Moreover, Chiang’s bureaucracy did everything possible to ensure a hospitable stay for US troops – even though externally, his government made statements meant to preserve the nation’s face.

Bars for visiting soldiers were approved by the municipal police department and marked with English signs reading “in bounds”.

Health checks were instituted to control the spread of venereal disease and soldiers were required to fill out forms before taking licensed prostitutes out of the bars. One surviving “Registration Form for Outgoing of Waitress” from 1967 lists the cost of taking a girl home at NT$400, or US$10.

Taipei After Dark was written in the midst of this booming red-light district and describes the Zhongshan bars as being “on the pattern of the girlie bars that began to spring up in Japan in the 1940s and that have since spread to most big Eastern cities.

“They are relatively small and simple, each one consisting of an American-style bar and bar stools, a small dance floor with a jukebox, and booths that are cramped enough so that there has to be plenty of contact”.

There was, however, a distinction between bars, which employed prostitutes, and clubs, where bar girls, most of them university students, would generally draw the line at chatting and drinking with customers.

They sold ‘honey’: prostitutes and ‘kept women’ in 19th century Hong Kong

Soldiers visiting on R&R, however, didn’t even have to hit the bars to find girls. “The government, in fact, allowed and encouraged people to make their arrangements the minute they got off the plane,” recalls Goldsmith.

As soldiers disembarked at Taipei International Airport, they encountered tables of tour-guide operators, who offered a five-day tour package with a female “tour guide” included.

“And anybody who had a brain in their head, who had been in Vietnam and wanted rest and recreation, was going to buy.

“Basically, Taiwan became one of the most attractive places in the world for our Vietnam servicemen to go on their rest and recreation tours,” says Goldsmith.

When he invited a group of Vietnam vets to discuss R&R 35 years after the war’s end, he recalls, “For these men, it was the most exciting week of their lives.”

Today the Zhongshan bar district is known simply as the Combat Zone. No one knows exactly where the name came from or who coined it, but most believe it emerged in the 1980s, after the US military had already pulled out of Taiwan.

The designation was likely bestowed by Taipei’s next generation as a nod to the area’s military legacy. However, no contemporaneous accounts from the era of US bases, including Taipei After Dark, Goldsmith’s novel Jade Phoenix, or blogs and social media groups by US veterans who served in Taiwan, ever refer to an area called the Combat Zone.

The keystone of this district was the US Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), which was located in Zhongshan North Road at the northern extreme of the bar district.

This large compound was the centre of US military life in Taipei and included administrative offices, the Navy Exchange (a military department store), a cinema, a bowling alley, military clubs and base housing.

After the US broke off formal diplomatic relations with Taiwan in 1979, the MAAG headquarters, along with all other US military installations, was vacated. Taiwan authorities soon demolished the compound and replaced it with civic-minded projects.

Today, the site holds the sprawling gardens of the Flora Expo Park and the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, places where families go for evening strolls and high school kids practise breakdancing. But what remains of the old military bar zone is just a short walk away.

“Overall, the Combat Zone was created as the US-Taiwan Defense Command began reducing personnel [during the 1970s] and the bars along Zhongshan North Road slowly began collapsing closer to the gate,” Minnick explains.

Following the end of R&R in 1972, the badly diminished military clientele was gradually supplanted by a rising tide of Western businessmen, who began flocking to Taiwan for cheap manufacturing.

Along with Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea, Taiwan had become one of the “Asian Tigers”, its factories pumping out everything from Barbie dolls to athletic shoes to cheap electronics.

Thank goodness for Taipei’s National Palace Museum

By the 1980s, the new Combat Zone was booming. But the location now was a few blocks north of the old GI bars and centred on a densely packed stretch along Shuangcheng Street – just a five-minute walk from the old MAAG gate.

The Zone became a mix of Vietnam-era girlie bars (which were increasingly viewed as “rip-off joints”) and newer Western-style pubs, some of them expat-owned, with dartboards and house bands playing rock ’n’ roll.

The Zone’s oldest remaining bars, My Place, the Manila, the Green Door, and Patina, date back to this period. Of these, only the Manila still has bar girls and, just as in the 1970s, many of them are college students.

I have had sources who do not remember telling me something serious. I write the story and when I see them on their next visit to Taipei they say, ‘Wow, how did you get that story?’Wendell Minnick on his blog, China In Arms

By the time Minnick discovered the Zone in the 1990s, it was beginning a slow, steady decline.

Describing it in the 2000s, he wrote in a recent blog post, “The Combat Zone was not Bangkok’s Soi Cowboy, nor Angeles City’s Santos Street, nor Singapore’s Four Floors of Whores. The Combat Zone was gaudy, idiotic, nasty. The glory days of the 1980s economic boom were a faint memory.”

And yet for some unknown reason, US military types continued to sift into the Zone’s ever-seedier watering holes. Only now, they were wearing civilian clothes. Sometimes their own embassy didn’t even know they were on the island.

On his blog, China In Arms, Minnick describes a cabal of dozens of special envoys – “an alphabet soup of government acronyms” and “a list of dramatis personae that Taiwan’s military had not seen since 1979” – who began pouring in during the 1990s in an effort to shore up Taiwan’s military capabilities and ability to defend itself.

As Taiwan no longer had formal diplomatic relations with the US, these fact-finding missions were uniformly low key. Some were technically covert.

“By 2000,” Minnick writes, “the volume of delegations forced me to move to an apartment five minutes away.”

“Bar girls would send me a phone text if they showed up in any of the pubs in the Combat Zone. And at any time of night, I would simply crawl out of bed, gargle with beer from the fridge, light a cigarette, and walk around the corner. US military personnel and US defence contractors thought I was an alcoholic.”

For Minnick, “The Combat Zone served as a non-stop buffet of breaking stories.”

“I have had sources who do not remember telling me something serious,” he wrote on his blog. “I write the story and assign him as a ‘Pentagon source’. When I see them again on their next visit to Taipei they say, ‘Wow, how did you get that story? My boss went apes***.’”

Minnick is now in his sixties, and while still as burly, imposing and hawkish as ever, he’s also begun to mellow in various, subtle ways.

In the past few years, he has begun looking back over his decades of research and reporting, combing through his own articles as well as stacks of newspaper clippings on every sort of bizarre, Taiwan-related incident of espionage or military intrigue since the 1950s. He now publishes these on China In Arms.

“Here I am in my sixties going through all my old files. It’s time. I don’t want to leave all this stuff for my wife,” he explains.

His reissue of Taipei After Dark is also part of this taking stock.

This kind of information might not be politically fashionable these days, but that doesn’t mean we should forget about itWendell Minnick on republishing Taipei After Dark

At the time he discovered the book’s existence, he recalls, “there were only a few copies on the internet, and they were selling for US$100 each. I knew it was going to fade from view”.

As he was already selling his own self-published books on Amazon – including at least two dozen meticulously compiled encyclopaedias of Chinese aircraft, missiles and military vehicles along with other directories for military specialists – adding Taipei After Dark to his publishing catalogue was not difficult.

To update the book, he added a new introduction and appendices of bar maps, photographs, newspaper advertisements and other factual materials that point to the guide’s legitimate historical basis in fact.

He estimates that he has sold about 1,000 copies so far and he has just come out with a second edition including yet more documentation pointing to the guide’s factual underpinnings.

Sipping on his Budweiser, he says, “Not everybody cares about history, but I do. This kind of information might not be politically fashionable these days, but that doesn’t mean we should forget about it.”