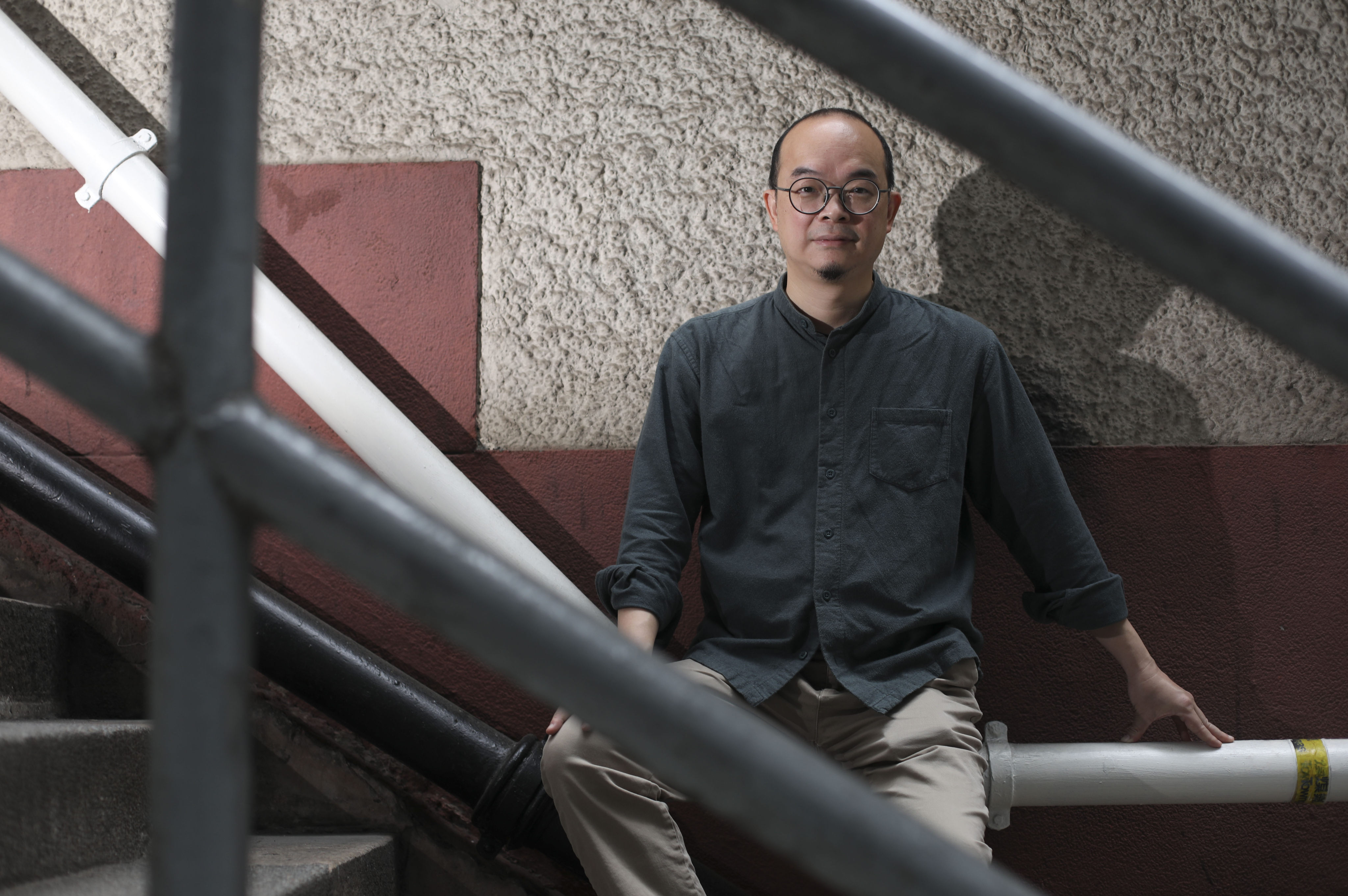

- Tozer Pak stopped going to church but sees God’s work wherever he goes. He tells Kate Whitehead about using art to inspire young people with autism and ADHD

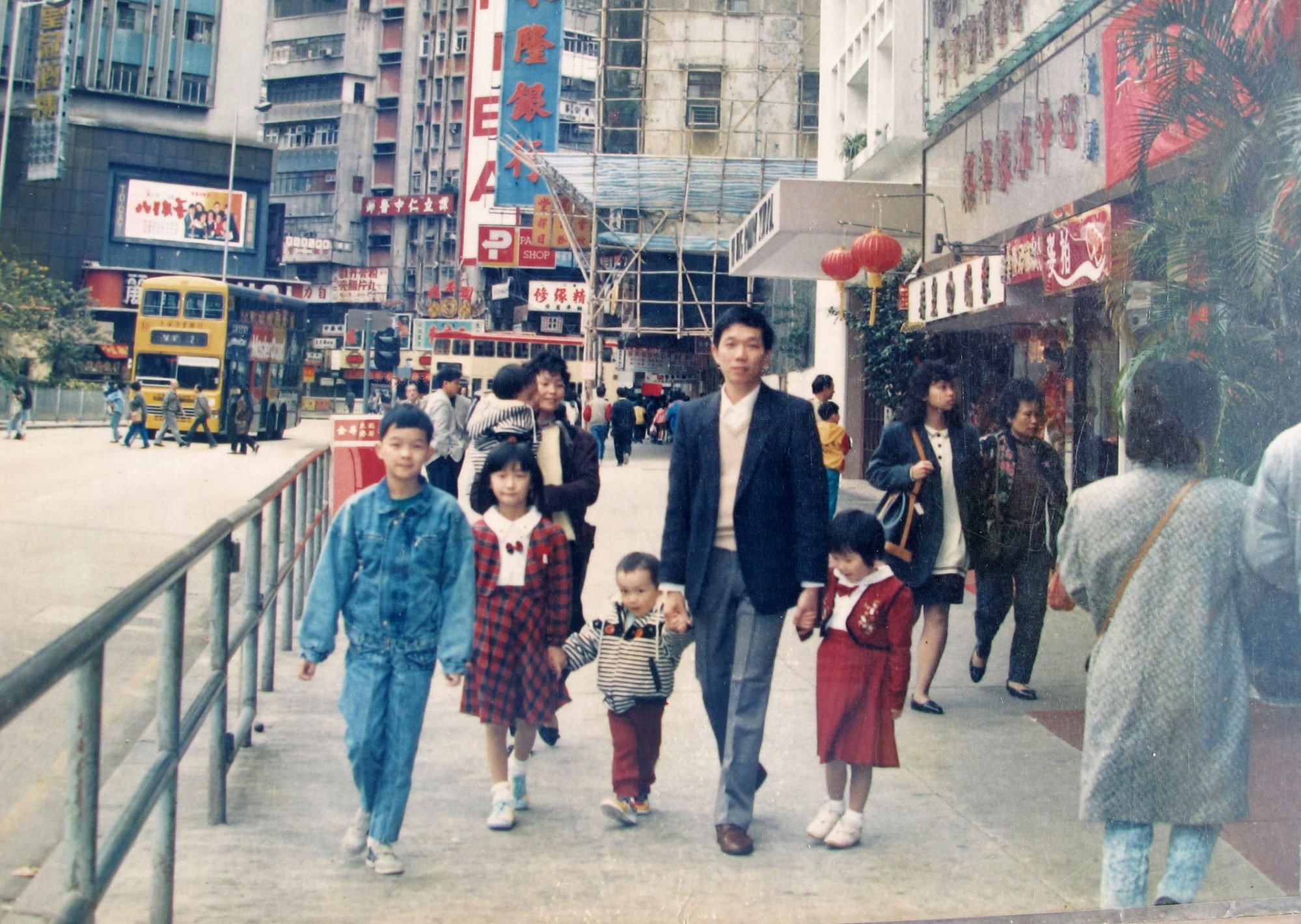

My parents are both from Fujian province in southeast China. My father moved to Hong Kong for work. In China, Hong Kong was seen as a city where your dreams could come true, it could be life-changing.

Initially, he worked at a Chinese products store and when my rich great-great-uncle, who lived in Singapore, opened the three-storey Sanki Department Store in Western district on Hong Kong Island, he began working there.

In 1984, my mother and I moved to Hong Kong and lived with my father in a very small apartment. My sisters stayed behind and were looked after by our grandparents.

After the freedom and space of growing up in the countryside, the living conditions felt very cramped.

After a couple of years in Hong Kong, my twin brothers were born – all of us living in one room – and a few years after that, my sisters joined us.

‘Essential to the culture’: why Hong Kong’s cha chaan teng are worth saving

Our father

In Form One, I joined a summer Christian camp with one of my teachers, who took me to a very traditional church, the Hephzibah Evangelistic Centre. In the church, the boys and girls were separated.

The missionaries told us how Jesus was crucified as a sacrifice for everyone and said that if we believed this, to raise our hand. My heart was beating fast as I raised my hand and was asked to go to the front, where we all prayed together.

Woman of my dreams

The church became my life. I went to church every Saturday and Sunday for 10 years. The Bible said you must obey the law, so I didn’t even dare jaywalk. I even went through a period of thinking about becoming a missionary.

On the outside I was very obedient, but I experienced a lot of internal conflict, especially during puberty. The brothers taught us to pray and said that, in our prayers, God would tell us who would be the one to marry. But I never got such a message.

It seemed an unnatural way to meet someone and none of my classmates were doing it that way. My heart was broken.

The church taught me to know what I really want and love and to follow thatTozer Pak

An epiphany

I met my future wife, Kam Lai-wan, at university. She was my classmate and my first girlfriend. She wasn’t Christian. I told her that we couldn’t continue our relationship if she didn’t believe in the Christian faith. She went to church for a year, but it wasn’t for her.

During that time, I changed, and I began to think that only following the guy in the church wasn’t that important; it was about the people you interact with every day.

After I graduated, in 2002, I stopped going to church, but my life still felt like that of a religious person. The church taught me to know what I really want and love and to follow that.

Divine inspiration

A Ming Pao editor went to the exhibition and selected a few artists to create some artwork in the newspaper and I was one of them. Within a few months, I had a weekly column, and I developed a new style of working.

I responded to stories and topics in the news and learned to work quickly and interact with society.

Since I was no longer going to church, I often felt confused, and I developed the habit of walking around the city and jotting down in my notebook things that caught my attention.

I’d notice the way the light fell, and it felt like inspiration from God, but it wasn’t the same God I’d worshipped before; it gave me fulfilment. I wrote notes of these observations every day and developed a huge ideas bank that I could draw on; I even drew up an Excel sheet of my observations. It was a healing process.

Going stateside

In 2007, I got a grant from the Asian Cultural Council to go to New York for a year. I was given money to buy books and go to the cinema, even to travel. It was an incredible experience and very generous. I joined some artist and residence programmes and met other artists.

Court in the moment

I got married in 2009 and our son was born in 2013. Becoming a father made me think seriously about the family and our future. After that, I didn’t take up as many artist-in-residence offers.

I didn’t know how to get help, so I started going to the courts. As I listened to the court cases, I let my pen create an abstract form in my notebook. After a while, I focused on cases related to the social movement and created an exhibition from my drawings, “Nightmare Wallpaper”. I still go to the court and draw in my notebooks.

‘I cried from morning to night’: women with ADHD in China lack professional help

Moulding characters

In 2019, I was asked by the Hong Kong Jockey Club to work with the Boys’ and Girls’ Clubs Association to rethink the art classes for children with ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and autism.

Before every class, the students ran around and around, they couldn’t stop. The social worker explained they needed to run to release energy otherwise they couldn’t sit down.

I thought if we could contain that energy, it could be transformed and used in more productive ways. In our project, “Art Makes Sense”, we gave the kids a mountain of clay. They were able to mould it with their hands, giving them a strong sensory feeling.

They not only calmed down, but they could see their energy had been released in a positive way, that they had produced something.

Positive reinforcement

The goal is to work towards true inclusivity and diversity in society. When we look at disabled or SEN groups, we don’t treat them as having a problem, they have their own characteristic and it can be transformed into something very strong.

I’ve just returned to Hong Kong from two months of teaching at Tainan University, in Taiwan. I really missed Hong Kong. The energy of Hong Kong – the speed, the diversity – is important for me. I really love Hong Kong and I’m happy to work in this city.