- He was a stuntman for Jackie Chan in Hong Kong and Hollywood, then action director on Dwayne Johnson movies and Marvel’s Shang-chi. Andy Cheng looks back

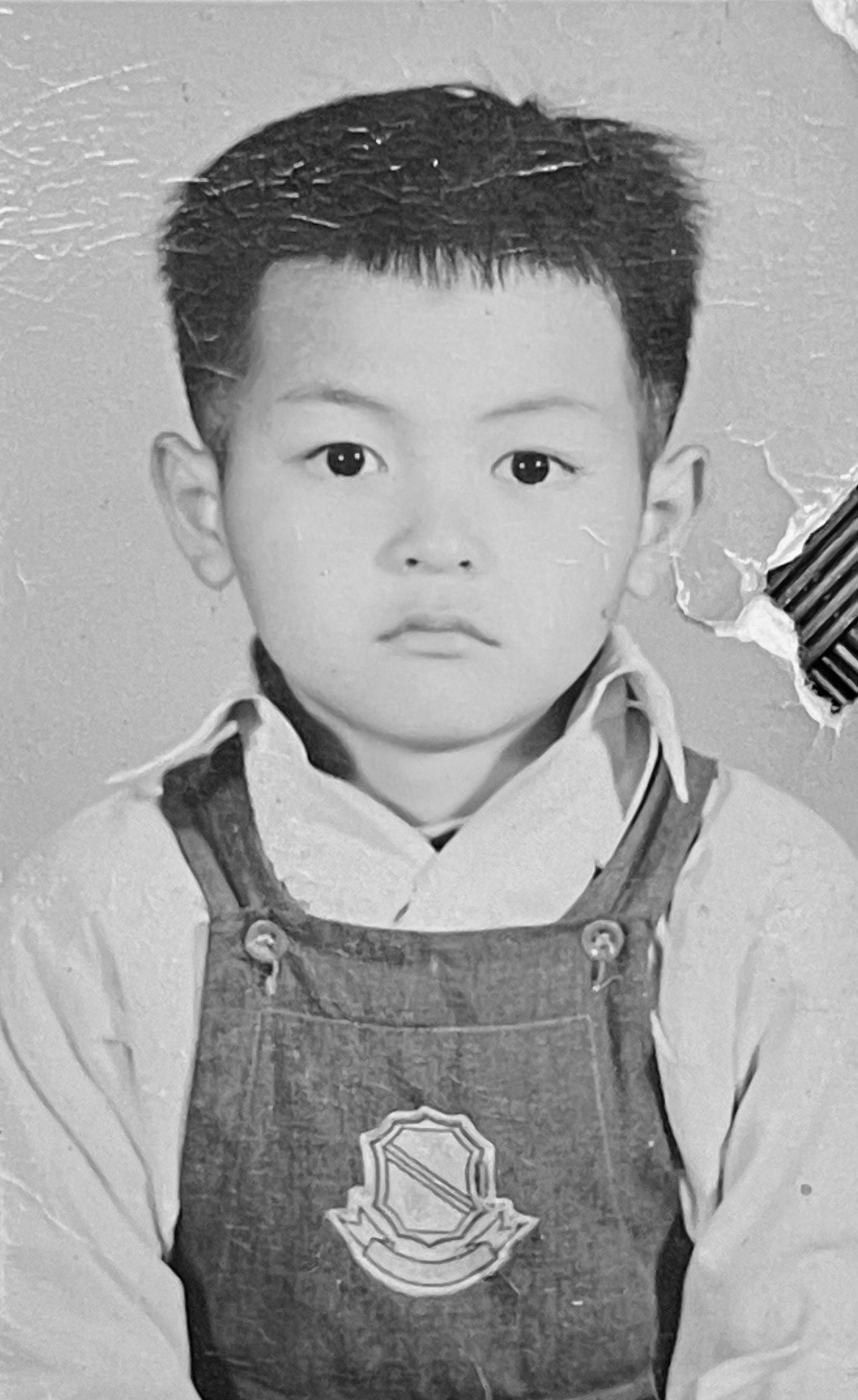

From humble roots in the Hong Kong neighbourhood of Kwun Tong, Andy Cheng Kai-chung has risen to become one of Hollywood’s top action directors and fight choreographers. He recently achieved international recognition for co-choreographing an innovative sequence in Marvel’s Shang-Chi and The Legend of the Ten Rings.

For many, it was their first time hearing the name Andy Cheng, but he already has a list of credits that include being international taekwondo champion, a stuntman and stunt double for Jackie Chan, and a fight choreographer for martial-arts legend Sammo Hung Kam-bo.

“I was a street kid, and I had no money to do anything. There was a hung gar school, but I didn’t have enough money to go, as it was HK$10 a month. I learned a bit of hung gar on the street, but I had no proper lessons.”

I was crazy about it for 15 yearsAndy Cheng on taekwondo

Cheng started studying martial arts seriously at school.

“Everybody had to pick a hobby, like playing in the school band. I really wanted to learn martial arts, and there was just one course at the school – taekwondo. It was taught by a Korean master who came to the school on Mondays and Fridays.

“I fell in love with it very quickly and in three months, I was a yellow belt.”

Cheng participated in his first tournament while he was a yellow belt, even though the rules said competitors had to be at least a green. He won a silver medal. “From then on,” he says, “I was crazy about it for 15 years.”

Cheng retired from competition after winning his bronze medal in the Asian Taekwondo Championships in Taipei in 1990. “Taekwondo is from Korea, and they have a very powerful team,” he says. “The Taiwanese are also very powerful, and they came second in the games. I felt that the bronze was the furthest I could go.”

By then, Cheng was performing stunts for Hong Kong’s Television Broadcasts (TVB), which was churning out wuxia – period-piece sword-fighting films – by the dozen.

“They offered training in three parts,” Cheng recalls. “Tumbling and wirework [a complex rigging system that is used to simulate flying], martial arts/weapons, and acting. You learned everything you could in those three months, and then they tested you. If you passed, you got a two-year contract.”

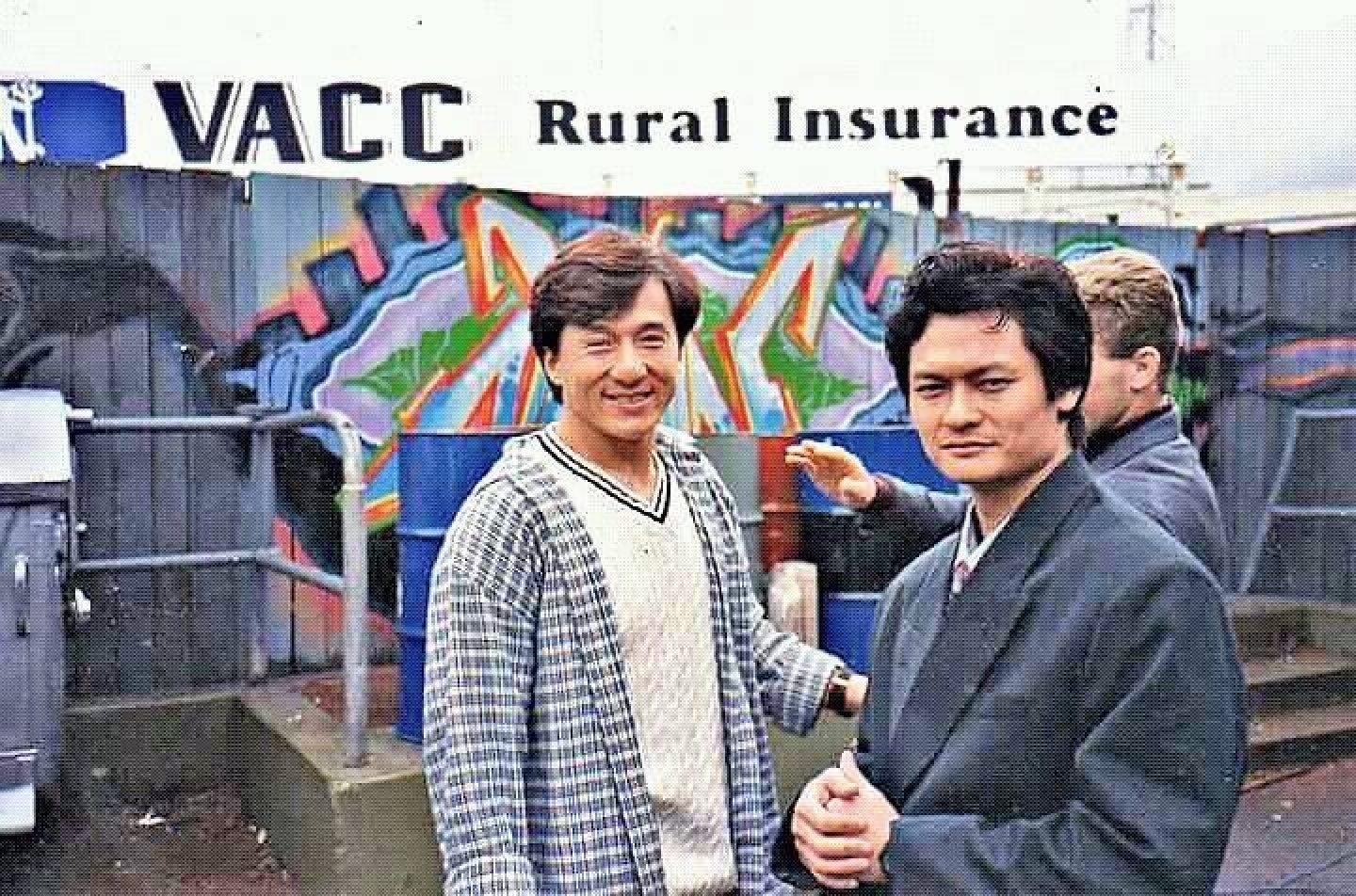

We were a good team. Jackie likes to work with people he trusts. That way, he can try new ideas.Andy Cheng on working with Jackie Chan

For six years, Cheng recalls “doing 25 shows a month – if you worked as a stunt double, you got double pay, and if you worked nights, you also got double pay. I would work during the day outside on location and at night, I would work in the studio”.

Cheng started moonlighting as a stuntman in films while still contracted to TVB. While this was accepted as long as it was kept quiet, a picture of him on a film set appeared in a newspaper, and TVB let him go.

“Sammo and Jackie are both legends,” says Cheng, who as a youth would slide down the same concrete bank in Kwun Tong that Chan used for a well-known stunt in the Police Story franchise.

“Their action director, Cho Wing, called and said, ‘Do you want to work with Dai Go [Big Brother, Chan’s industry nickname] and Dai Go Dai [Big, Big Brother, Hung’s nickname]?’ I said yes straight away.

“It was an honour, but there was also a lot of pressure. Sammo can ask you to do crazy things, so I knew it would be a challenge. To be honest, I thought it would kill me!”

Cheng worked on a number of films between 1997 and 2002 for Chan, including Who Am I?, Rush Hour, Rush Hour 2, and Shanghai Noon, often acting as a stunt double/stand-in if Chan was injured and couldn’t perform a certain move.

Cheng often appeared as a henchman in fight scenes, and would receive a pasting from Chan. But, says Cheng, “after working with him on Mr Nice Guy, I understood more about his style and what he liked to see. That proved to be a good foundation for our relationship.

“By the time we got to Rush Hour, we were a good team. Jackie likes to work with people he trusts. That way, he has less to worry about, and can try new ideas.”

The stunt performers are “close, like brothers and sisters”, says Cheng.

“I got really close to the team while making Who Am I?, which we filmed in Africa. We all lived together in a big house, we ate together and we went to the movies together. We even went shopping together at the weekend. Jackie was our Big Brother, he took care of everything for us.”

And Cheng’s loyalty to Chan runs deeper than the stunt team.

Hong Kong action dominated Hollywood for 10 years, then things slowed down. But now it is coming back.Andy Cheng

Chan once saved his life when a stunt involving a boat in Hong Kong’s Victoria Harbour went wrong during the filming of Rush Hour 2 in 2001.

Cheng had to fall into the water from a six-metre-high moving boat, but, since “we didn’t shut down the engines, they created a current and under the boat, two big propellers were moving the water like a fan, and I was sucked to the back end of the boat, spinning like I was in a washing machine. I held my breath, but I knew I could not hold it forever”.

There was no safety diver in the water. “It was dark, and no one on the boat could see anything,” he says. “They were trying to see me back near where I had fallen in, 500 feet away, and they shone a light there to search for me. But I was actually right below them.”

Cheng recalls feeling close to death, and one of his last thoughts was that he had let his father down.

“My Chinese name, Kai-chung, means ‘continue the family name’, and I kept thinking that, as I did not have a son, I had failed. I kept thinking that if I died, my father would die, too.

“I was talking to myself, saying, ‘Andy Cheng, this is no fun any more.’ It was odd, as later I remembered that I had all these thoughts in English, and my English was not good back then.”

The boat had a jet ski platform attached to the back, and that was what saved Cheng, spinning in the boat’s wake. That, and Jackie Chan’s big hands.

After searching where the others were not, Chan spotted Cheng, and “Jackie jumped down onto the jet ski platform and reached in to get me.

He has big hands – he grabbed me by my shoulder, which is a difficult part of the body to grab, and I was saved. I really thought I was going to die that day.”

Cheng left the Jackie Chan Stuntmen Association in 2002 to continue his career in the US, where he joined Stunts Unlimited and worked as stunt coordinator and fight director on The Rock’s Scorpion King (2002) and The Rundown (2003), and as stunt coordinator on the film adaptation of Twilight (2008), among others.

He also directed a feature, End Game (2006).

The two had a whole year to design and film the scene, something unheard of in Hong Kong’s quick-fire film industry.

“If we did that scene in a Hong Kong film we probably would have just done it on a real moving bus, filming the fighting inside,” says Cheng, who has often praised the spontaneity of Hong Kong stunt choreography.

“It would have been much shorter, and much more dangerous to film.”

His new production, NRCity, a film and streaming project by German company Adrenalizing Films, has been specially developed to make use of Cheng’s talent for action. He will be in charge of behind-the-scenes action creation and will direct the scenes.

“I will be fully in control of the action, and I’m excited to see how far I can take it.

“All the characters have a special skill. They use different styles of combat, and they are all different nationalities. Everything is mixed together. Everything is ready to go on the project, and I’m really excited about it.”

“I came here early on for Rush Hour and Martial Law, and they were also shooting The Matrix,” he says. “Those were the first-ever Hollywood movies to have a full-on action package in the Hong Kong style.

“This is the second Asian wave,” he says, “and this time we are going much further.”