- The Toyota Prius hybrid and all-electric Nissan Leaf had early-mover advantage, so why is no Japanese company among the top 20 makers of electric vehicles now?

Spectators at the United States’ Nascar Cup Series race in November last year had front-row seats for a debate over the auto industry’s future.

A plane sponsored by non-profit group Public Citizen flew past Phoenix Raceway in Arizona carrying a banner that read: “Want exciting? Drive electric. Want boring? Drive Toyota.”

The fly-by followed an open letter to Akio Toyoda, CEO of one of the world’s largest carmakers, from groups including Public Citizen criticising its slow roll-out of electric vehicles.

“No carmaker has been able to keep up with the surging consumer demand for battery electric vehicles, but Toyota has not even attempted to meet it,” they wrote. “Toyota can and must shift swiftly to EVs or risk obsolescence.”

While the NGOs’ motivations were green ones, their message reflected a wider concern in the US$2.25 trillion global car industry that Toyota and other Japanese carmakers risk losing their leading position by failing to shift to electric vehicles (EVs) fast enough.

Tesla is the world’s top EV maker by vehicles sold, followed by companies including China’s BYD and Germany’s Volkswagen, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. No Japanese carmaker makes the top 20, leaving them on the sidelines of the auto industry’s fastest-growing sector.

How an American revolutionised China’s rug-making game in the 1920s and ’30s

For the first three quarters of 2022, sales of battery-powered vehicles grew about 80 per cent from a year earlier, while total vehicle sales fell about 4 per cent, according to Bloomberg data.

“It’s becoming a material part of the industry, and so far the Japanese are missing out on that,” says Colin McKerracher, an analyst with BloombergNEF.

Japan’s biggest auto brands have long been consumer favourites around the world, typically accounting for more than a third of new car sales in the US, and dominating markets from Southeast Asia to Africa.

Their absence from the EV segment is particularly baffling because of their early start with eco-friendly vehicles, including Toyota’s Prius, the mass-market hybrid launched a quarter of a century ago and one-time top pick of Hollywood stars seeking green credentials.

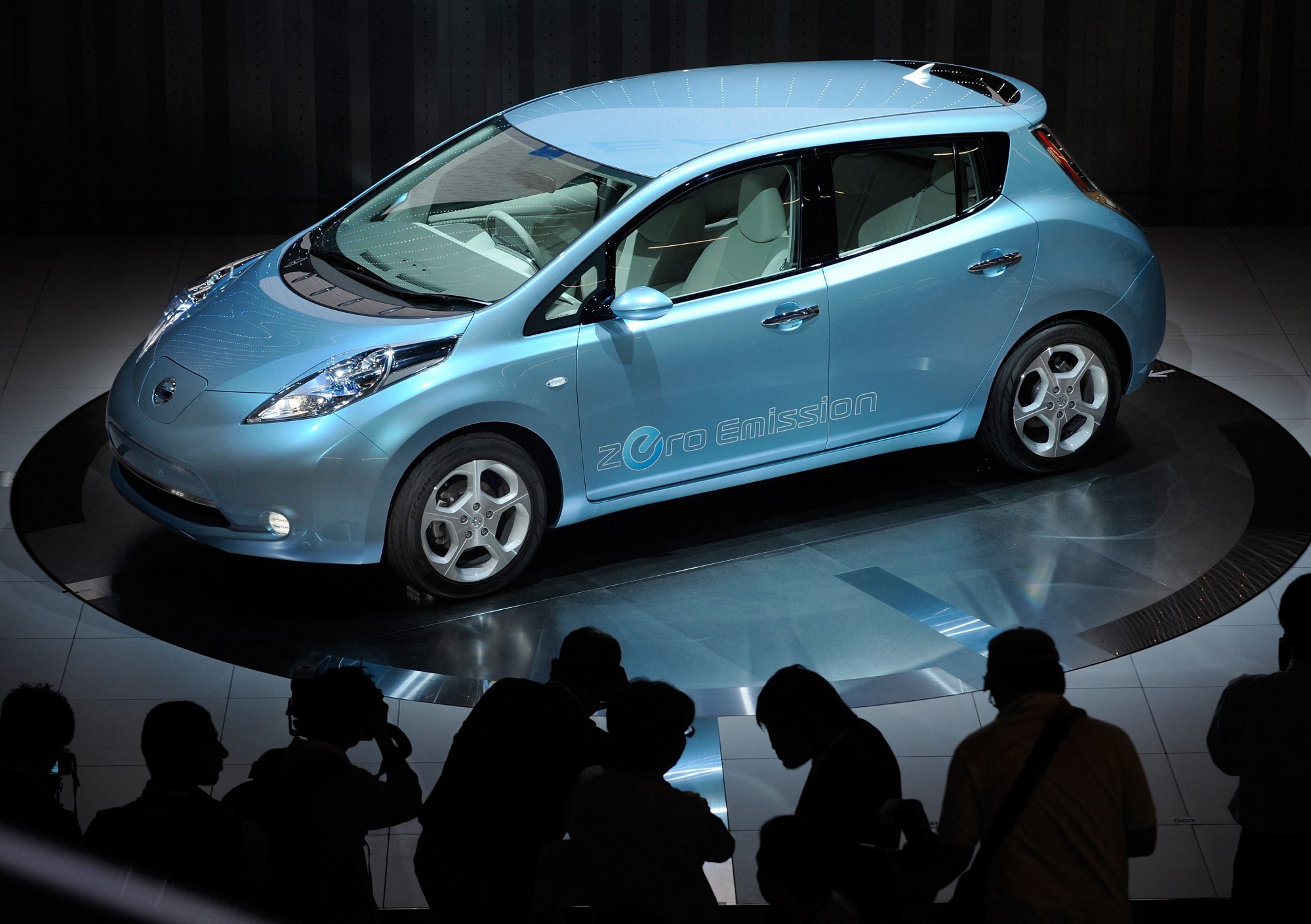

In 2009, Nissan Motor unveiled the Leaf, an all-electric hatchback considered a pioneer in mass-market EVs. That same year, Mitsubishi Motors also launched its first EV, the MiEV. In 2010, Toyota invested in Tesla.

Enthusiasm over the early EV models, though, quickly faded due to tepid sales. Convinced the battery revolution would happen slowly, Japanese carmakers focused on petrol-electric hybrids and cooperated with the ambitions of Tokyo technocrats to develop hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles, a nascent technology with potential to be even greener than EVs.

The Japanese car industry needs to catch up. It already could be too lateFormer Nissan executive Masato Inoue, chief product designer of the Nissan Leaf

The Japanese car industry needs to catch up,” says former Nissan executive Masato Inoue, chief product designer of the Nissan Leaf, who now teaches at the Istituto Europeo di Design, in Turin, Italy. “It already could be too late.

Last September, Toyoda said battery electric vehicles (BEVs) “are just going to take longer than the media would like us to believe”. The company also says it is on a mission to reduce carbon dioxide emissions but does not want to limit its focus to all-battery cars.

“In this diversified world, in an age where we do not know what the correct answer is, it is difficult to make everyone happy with only one option,” the company said in a statement.

The battery vehicles they do sell can be disappointing: last May Toyota launched the bZ4X electric SUV but halted sales in June because a defect could cause its wheels to fall off. Sales have since resumed, albeit in limited quantities.

“The Japanese car industry needs to catch up,” says former Nissan executive Masato Inoue, chief product designer of the Nissan Leaf, who now teaches at the Istituto Europeo di Design, in Turin, Italy. “It already could be too late.”

His former boss, ex-Nissan chairman and early champion of the Leaf, Carlos Ghosn, agrees.

“Nissan lost its early-mover advantage,” he says, predicting Japanese carmakers is likely to struggle to catch up with rivals including China’s BYD. Electrification investment announcements now “are too little, too late”.

While such criticism is to be expected from Ghosn, who was arrested in 2018 on charges of financial misconduct at Nissan, and lives in Lebanon after staging a dramatic escape from Japan, hiding in a bulky instrument case and bypassing a security scan at a regional airport, he is not the only one who is pessimistic.

Critics worry the carmakers are replicating the decline of Japan’s semiconductor and consumer electronics industries. These once reigned supreme with products such as NEC’s memory chips and Sony’s Walkman, but were caught flat-footed by major disruptions such as Apple’s iPhone and failed to innovate their way out of commoditisation.

“Japanese carmakers look like they’re already left behind, and incapable of taking a lead position,” says Shingo Ide, chief equity strategist at Nippon Life Insurance’s NLI Research Institute.

Six major Japanese carmakers had about 40 per cent of the US market for passenger vehicles in 2021, roughly the same as before the pandemic. But in the second quarter of 2022, their share fell to 34 per cent, and by the third quarter it was 32 per cent, according to Bloomberg data.

General Motors last year took Toyota’s crown as the top seller in the US, with the Japanese company reporting its US sales fell 9.6 per cent in 2022. As more Americans choose EVs, Japanese brands – for decades a top choice for everyone from first-time drivers to suburban housewives – are the biggest losers.

“Consumers moving to electric vehicles in 2022 are largely doing so from Toyota and Honda – brands which have been unable to keep their internal combustion owners loyal until their own brands begin to participate more significantly in the EV transition,” S&P Global Mobility said in a report published in late November.

One of the biggest issues is that some markets are shifting to EVs much faster than many anticipated. About 15 per cent of new cars sold in Germany and Britain and more than 20 per cent in China were electric in the first three quarters of 2022, according to Bloomberg data.

While EVs accounted for 5 per cent of US sales during the period, demand is likely to jump thanks to tax breaks in the Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law in August 2022. By mid-December, companies announced almost US$28 billion of investment in EV-related manufacturing in North America.

Toyota “has substantially miscalculated” in its EV strategy for North America, write Jefferies analysts Takaki Nakanishi and Jingfei Deng.

Toyota’s pursuit of hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles is backed by the country’s trade ministry, which believes that hydrogen is key to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050.

The government said last June that by 2035 all cars sold should be “so-called electric-powered vehicles” with the proviso that hybrids are included.

With an electric vehicle, basically half of Nagoya [a city full of car part manufacturers] becomes unemployed. The growth potential of the Japanese economy is definitely shrinkingJesper Koll, director of Monex Group financial services company

With an electric vehicle, basically half of Nagoya becomes unemployed

Japan’s carmakers and government leaders have been reluctant to push for a pivot to all-electric for fears it would cannibalise existing car sales and devastate a broad network of parts suppliers and subcontractors. EVs generally don’t require as many components as traditional cars.

Vehicle production is one of Japan’s most important industries, accounting for almost 20 per cent of manufacturing in the country and 8 per cent of employment, according to a report by the Climate Group, an environmental organisation.

Toyota has promised to keep making about three million cars in Japan – around a third of its global output – to maintain employment and competitiveness.

“With an electric vehicle, basically half of Nagoya becomes unemployed,” says Jesper Koll, director of financial services company Monex Group, referring to the city in central Japan near Toyota’s headquarters and where many parts manufacturers are based. “The growth potential of the Japanese economy is definitely shrinking.”

Realising that EVs are no longer the niche product they once were, however, Japanese companies are now stepping up investment projects, with Toyota spending 4 trillion yen (US$30 billion) to launch 30 EVs by 2030.

Honda is co-developing an electric SUV with General Motors for a 2024 debut and has another partnership with Sony to deliver premium EVs starting in 2026.

Nissan, which began delivering Ariya electric SUVs to US customers in December, has boosted spending to introduce more models.

Rivals are also picking up their pace with EVs. General Motors has been moving particularly quickly and may surpass Tesla in EV sales in 2025, according to Bank of America analyst John Murphy.

General Motors’ EV portfolio includes the Chevrolet Bolt hatchback and compact utility vehicles Cadillac Lyriq SUV and GMC Hummer pickup, and the company expects to launch several more EVs this year.

Executives at Toyota say all-battery cars are still too expensive or unfeasible due to lack of charging infrastructure in many markets, particularly in the developing world.

The average EV price in the US was about US$65,000, compared to more than US$48,000 for all new vehicles, according to a Kelley Blue Book report published in December.

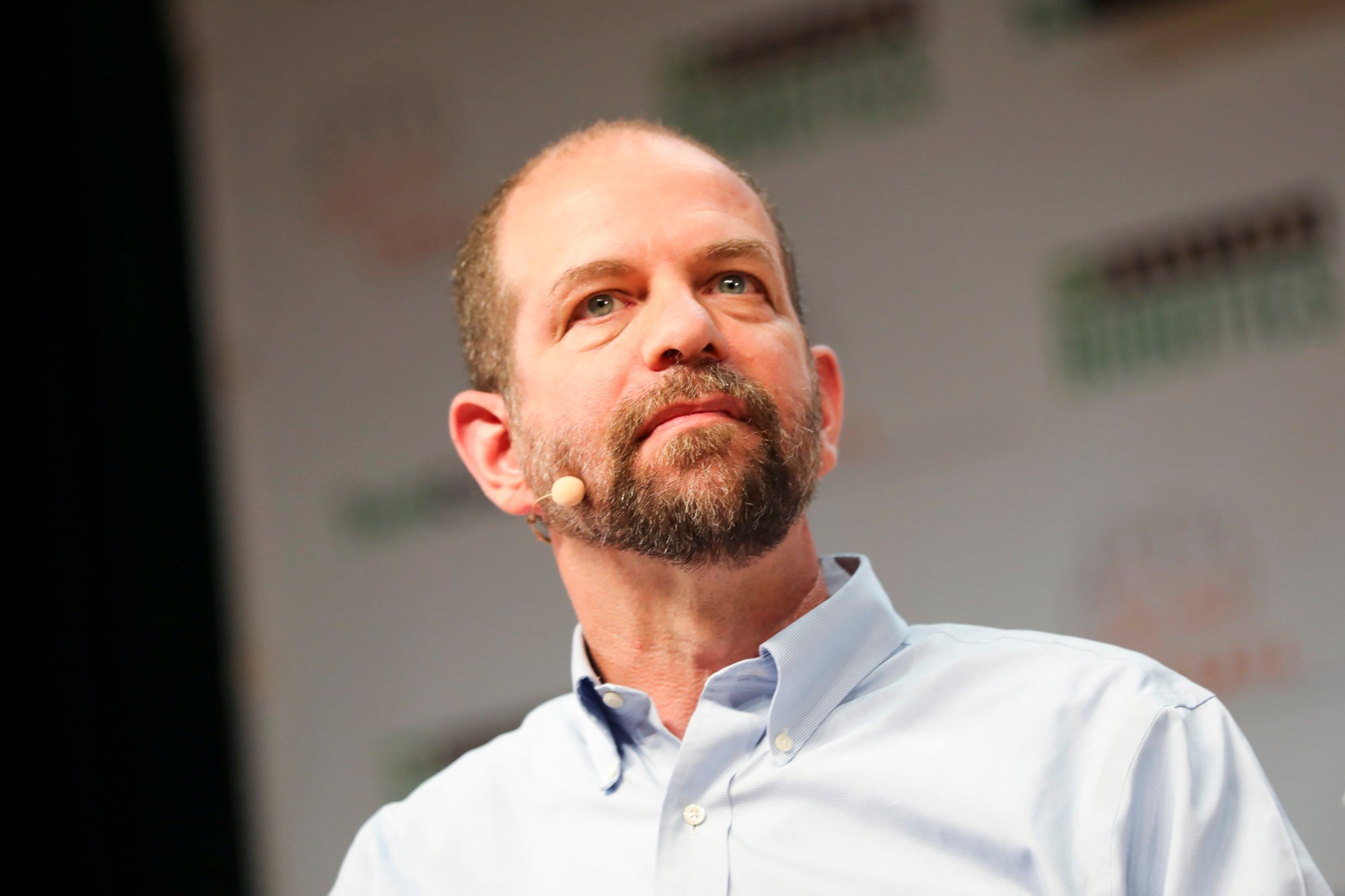

Gill Pratt, Toyota’s chief scientist, notes that many countries lack the charging infrastructure to sustain EVs, saying a mix of EVs, plug-in hybrids (PHEVs) and hydrogen-powered vehicles (HEVs) is the most realistic option in those markets.

“For these places and for customers without easy access to recharging infrastructure, PHEVs and HEVs are the most effective way to lower their carbon footprint,” says Pratt. “It is also the best way for net carbon emissions to be reduced as much as possible, as soon as possible.”

For all the challenges they face from nimbler players, Japan’s top carmakers retain many advantages accrued during their years at the top of the heap. Having spent decades catering to mass-market consumers, they boast powerful brands as well as distribution and service networks that EV newcomers cannot match.

Chinese rivals such as BYD are still largely unknown in many countries and lack experience serving global customers.

Even if you have all the resources and capability of Toyota to produce an EV when you’re ready, you still have to go through a learning curveKarl Brauer, executive analyst at iSeeCars.com

“I would never count them out,” says Michelle Krebs, executive analyst with Cox Automotive, speaking about Japan’s carmakers. “They’ll still be in the game.”

Yet analysts say catching up won’t be easy for the Japanese, as the competition around EVs shifts from traditional, mechanical engineering to software and services. The companies, with their late start, are missing out on the chance to get to know their EV suppliers and customers before their rivals do, says Karl Brauer, executive analyst at iSeeCars.com, a website that ranks cars and dealers.

“Even if you have all the resources and capability of Toyota to produce an EV when you’re ready, you still have to go through a learning curve,” he says. “And the other carmakers are ahead of you, because they’re doing it now.”