- From elevating the neglected Tanka community to bringing their dragon boat races to the masses, Charles Thirlwell’s legacy still resonates in Hong Kong

There is no official memorial in Hong Kong to commemorate Charlie Thirlwell. No parks, roads or public buildings bear his name. But his legacy compares favourably with that of any governor or wealthy merchant from the city’s past.

He fought for them to be integrated into mainstream Hong Kong society during the post-war period of rapid economic development. Thirlwell championed inclusivity and diversity in the workplace, six decades before the term was widely used.

He was awarded the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire in 1970 for his efforts.

Fluent in Cantonese and Tanka dialect, Thirlwell penned a dragon boating anthem that is still sung at festivals. “That’s why he is still known as the father of the fishermen,” says Lai Man-cho, treasurer of the Chai Wan Fishermen’s Recreation Club, which Thirlwell founded in 1964.

Lai has been a member of the Chai Wan club since its formation and he knew Thirlwell, who was close friends with his father. Back then, Lai says, club membership was just HK$2 per month but many fishermen still struggled to find the fees.

“I remember when I was six or seven years old working with my father on his trawler,” says Lai, “we would go ashore at Waglan Island, where Charlie worked as the lighthouse keeper and he would serve us with watermelon grown in his vegetable garden.”

The club still boasts some 300 members and occupies a modest ground-floor unit, set back from the road on the Yue Wan Estate in Chai Wan, at the eastern end of Hong Kong Island.

From Anita Mui to Kylie Minogue, Hong Kong’s disco days recalled

The walls are lined with glass cabinets packed with glittering trophies from dragon boat races, fading team photos and dust-covered bottles of beer. Thirlwell designed the club logo above the front door, and his monochrome photo portrait gazes down upon current chairman, Wong Kan-chai.

Wong insists that the club emphasises sport, dragon boats, socialising and drinking beer (no gambling is allowed). It’s not yet noon but a cold tin of Blue Girl beer is thrust onto the table and the stories of Charlie Thirlwell commence. This is traditional fisherman’s hospitality and it seems churlish to refuse.

Charles Beatty Allenby Haig Thirlwell was born in Hong Kong on September 6, 1918. His father, Captain James Thirlwell, was a well-known tug master who worked at Taikoo Dockyard. His mother, Elizabeth Dora Wilkinson, was a Macanese of Portuguese heritage and the devoutly Catholic family lived near the docks.

Charlie was our link with established societyWong Kan-chai, Chai Wan Fishermen’s Recreation Club

Charlie was the second eldest of 10 children and after a dockyard apprenticeship, he joined the lighthouse service in 1937, working one-month shifts at Waglan Island, a 10-hectare rock in the far southeast of Hong Kong territory.

“You know, in my day, being a lighthouse keeper was a bit like being a monk or a nurse,” Thirlwell told The Standard newspaper in an interview published on October 4, 1970, about a job he held for 27 years. “You had to have a real vocation for it.”

His father was killed in 1941, when his tug struck a mine while engaged on wartime naval duty in the Middle East, and mother and children were interned at Stanley Camp during the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. It was an experience that, his children say, he rarely spoke of.

“Dad was rarely at home and when he was, he was very quiet,” recalls his eldest daughter, Catherine Thirlwell. “He liked reading the Reader’s Digest and listening to his records, classical or pop music.”

It was a relatively short cruise from eastern Hong Kong Island to the rich fishing grounds around Waglan Island, and it was common for the fishing folk to barter fish and shrimp for vegetables or eggs from the lighthouse compound. Friendships grew based on a common affinity and respect for the sea, and Thirlwell went fishing with the younger men, teaching them signalling and basic English.

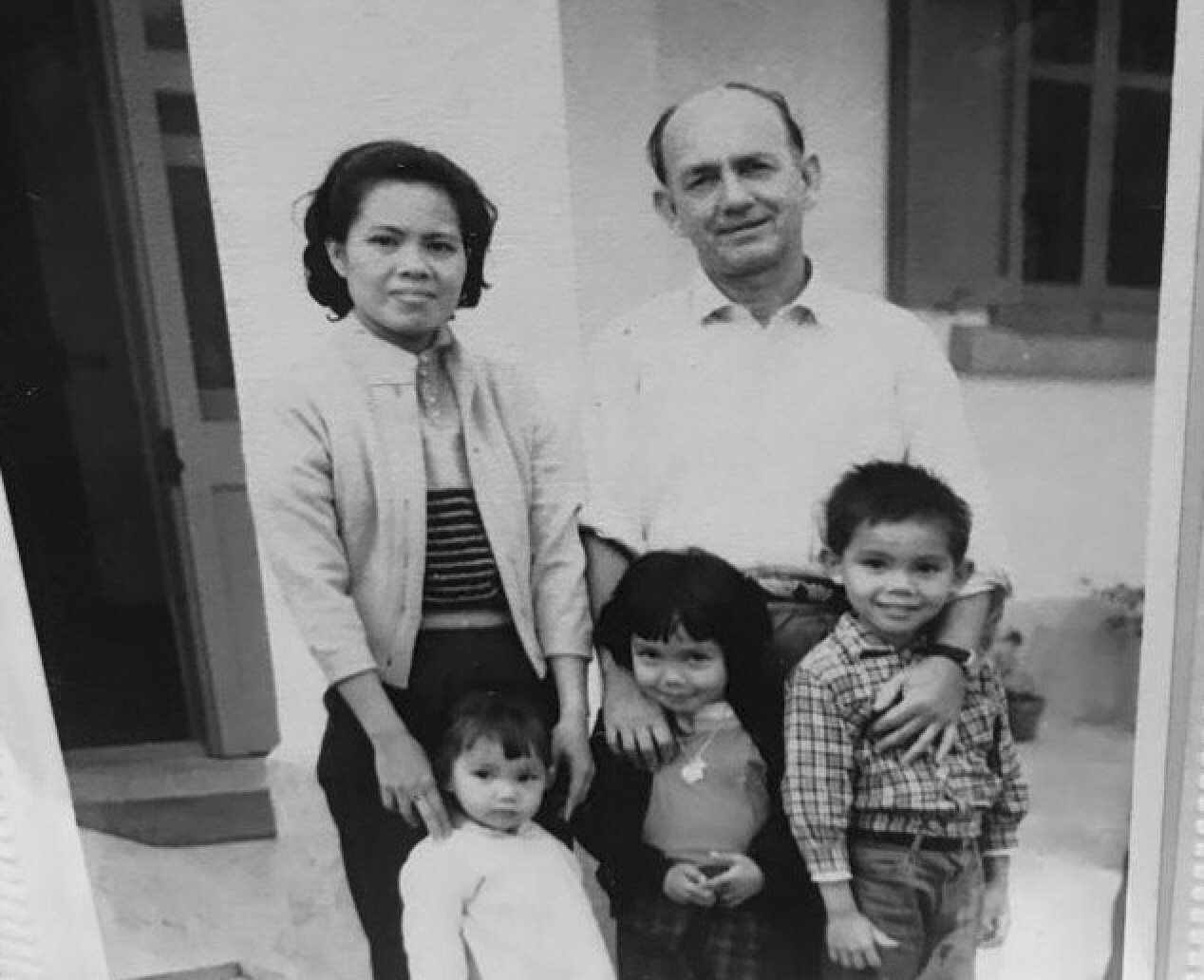

After an intermittent courtship, due to lighthouse duties, in 1953 Thirlwell married Mary Leung Wai-chung, a nurse at St Francis Hospital, in Wan Chai. Mary says her first impressions of Charlie were all positive. She felt that he was a “good boy and a very simple person”. Three children followed: James, Catherine and Christine.

Colonial Hong Kong in the 1950s and 60s was subject to rigid social hierarchies, prejudice and division, based on race, class, religion and gender. Marriage between Caucasians and Chinese was still something of a taboo. Growing up in Chai Wan in the 60s the Thirlwell children recall being blissfully unaware of these social barriers and their father paid little attention to them.

“We grew up playing with the local Chinese kids in Chai Wan,” says son James Thirlwell. “It was quite raw back then, fishermen, farmers and a few triads.”

He says he and his sisters never felt marginalised and remembers how his father’s friends came from all parts of Hong Kong society. Influential Chinese district councillors, colonial officials, lighthouse men, British civil servants, expatriate friends from the local Round Table group and fishermen, were all equally welcome.

“While the Tanka were ostracised at that time, we never had that feeling as we were growing up,” says Catherine. “We assumed we were all equals, they were just more of dad’s friends.”

His three children recall being taken to their father’s Christmas parties at Green Island, which would be swarming with people and loaded with beer. They could never understand how a man with such a solitary occupation had so many friends.

At the fisherman’s recreation club, Lai recalls a transformational time for the Tanka. “In the 1960s, mostly we were living in boats in the typhoon shelter and working as fishermen,” he says. “The government was trying to move us ashore and there was a big reclamation programme.”

Thirlwell obtained assurances from the government that the typhoon shelter would be reconstructed so that junk dwellers would be protected, and that flats would be provided for those who chose to come ashore: temporary resettlement units designed for immigrants from mainland China.

“At first, the fishing was still very profitable, so few came on land and they did not want a unit,” says Lai. “The older generation thought a boat was better; it’s what they knew and there was no rent to pay, so they were quite happy.”

In the end it was not government policies or reclamation that forced the fishermen ashore, but the lack of fish due to population growth and over-exploitation of local stocks. By the 70s, Tanka people urgently needed jobs – moving ashore was not optional, and it was Thirlwell who helped them make the transition.

I think it was Charlie who put dragon boat racing on the map. I remember he was always at the front, in No 1 positionChan Ying-lun, who was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1983

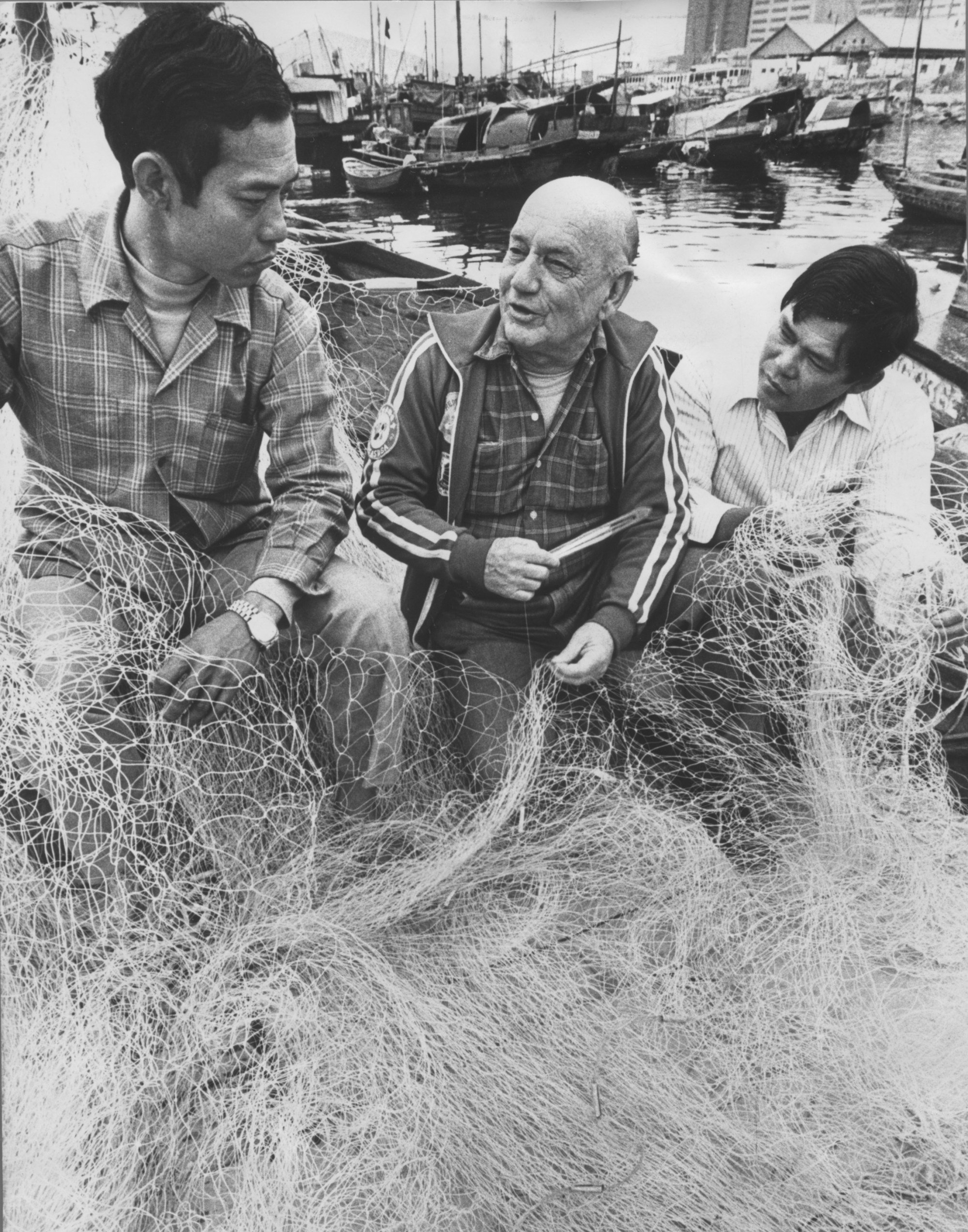

For people who had only known life on the water, the prospect of registering their births, deaths and marriages, compulsory education and working for a foreign government that spoke an alien language presented an intimidating challenge. Thirlwell worked tirelessly to teach them English, liaising with colonial government officials to obtain better housing and education for the Tanka.

“He was a trusted civil servant, so his word counted for a lot,” says Gordon Lai Chi-keung, club vice-chairman who was helped by Thirlwell to obtain a job in the Department of Health, where he stayed for more than 30 years. “Charlie helped so many people, it must have been tens of thousands, it was uncountable, not just individuals but whole families.”

“Charlie was our link with established society,” says chairman Wong, and Thirlwell had a gift for bridging divides and bringing people together with his humour and charisma, often lubricated with a beer or two.

After the Chai Wan Fishermen’s Recreation Club was established, it was common to see pilots from the local Australian air force base drinking there. Sailors from visiting Royal Navy warships rarely missed the opportunity. With Thirlwell’s support, more clubs were founded at Shau Kei Wan, Stanley, Lamma Island and Tai Tam.

“Back then the main purpose of the clubs was to act as a bridge between the fishing community and government departments,” says Wong. “People could meet here.”

And it was around this time that Thirlwell recognised the potential of dragon boat racing as a means to enhance the social status of the Tanka folk. Despite its long historical associations, dragon boat racing had a very low public profile in the 60s.

“In the old days, dragon boating was only done by the fishing community,” says club member and veteran dragon boat coach Tommy Ng Yiu-fai. “Each district had its own boat and competed with other districts.”

Then, in 1976, a young executive called Chan Ying-lun, working in the public affairs department of the San Miguel brewery, noticed an advertisement in the local newspaper for the Chai Wan Olympic Games. He was intrigued, went along to find the organisers, and met Thirlwell. They became friends instantly.

“The fishermen were very honest people, they earned their living from the sea and there was never room for any fierce competition or envy,” says Chan. “I immediately liked them very much and so did Charlie – that was the basis of our friendship.”

Chan went on to be elected as the Eastern district board member and was appointed to the Legislative Council in 1983, from where he worked closely with Thirlwell on the welfare and rehabilitation of fisherfolk.

“I think it was Charlie who put dragon boat racing on the map,” Chan says. “I remember he was always at the front, in No 1 position.”

Many influential individuals were invited to the dragon boat races, including VIPs, government officials – governor Edward Youde once attended as guest of honour – and Eastern district councillors. All were subject to friendly lobbying on behalf of the fishing folk.

The first international tournament was held in Shau Kei Wan in 1979, when a team from Japan competed, and by the early 80s the Hong Kong Tourist Association had realised dragon boat racing’s potential and it blew up.

“It’s now recognised as an international sport but it is still part of the culture of fishermen,” says Wong, who admits that until the 90s, females were not even permitted to touch the dragon boats, such was the strength of superstition and spiritual tradition surrounding the sport.

After his retirement, in 1973, Thirlwell took local dragon boat teams on tour to Japan, Australia and Taiwan, and devoted all his spare time to Tanka community issues. In 1984, he was appointed life president of the Joint Association of Hong Kong Fishermen.

“He was never ambitious or aggressive but his charisma attracted people,” says Catherine, and it seems that Thirlwell was both a quiet and introspective man who enjoyed the solitary nature of lighthouse duty, and also a creative soul who loved singing and storytelling.

His story had been largely forgotten outside the Tanka community until the City University Lighthouse Heritage Research Connections project, headed by Professor Steve Ching, in collaboration with the Hong Kong Maritime Museum, set out to compile a video documentary about the Waglan Lighthouse.

By chance the appointed narrator, Stella Leung Ka-yin, was related to Thirlwell’s wife Mary and told the researchers about her ancestor. Thirlwell’s remarkable story is now included in the video and also in a recently published book, Seeing in the Dark: Hong Kong Harbour and Lighthouses, published by the Hong Kong Maritime Museum.

Thanks in large part to Thirlwell, the Tanka fishing folk, rather than being castaways on their own island, became instrumental in the economic growth of post-war Hong Kong and its commercial port. Tankas provided maritime expertise and experience to the Marine Department, marine police, lighthouse service, dockyards, shipping companies and by offering innumerable informal port services from walla-walla water taxis to floating restaurants. And many continued fishing, of course.

In May 1985, Thirlwell’s community work was interrupted for a routine check-up at Queen Mary Hospital, and he was driven there by his old friend Chan.

“I drove Charlie to QMH that day and helped him into bed,” says Chan. “I remember he was concealed behind a pillar so the nurse could not see him properly and that was the last time I ever saw him.”

Thirlwell suffered a heart attack and died later that day. He was 66 years old. His funeral was organised by the local fishing community and held the following Saturday, May 11, 1985. The hearse carrying his coffin stopped at the Chai Wan Fishermen’s Recreation Club, which he had visited on most evenings during his retirement and where he had helped so many members.

Traditional street rites were held and hundreds of mourners from the local fishing community lined the streets. En route to the Chai Wan Roman Catholic Cemetery, the hearse paused at the Chai Wan waterfront, where four dragon boats had been moored in his honour.

Father Stephen Edmonds, a long-time family friend who conducted the funeral service, described Thirlwell as “a man with the ability of making other people laugh”. It was apt that the traditional Roman Catholic ceremony was held on the day of the Tin Hau Festival, celebrating the sea goddess who is the most revered deity to local Tanka fishermen.

The dragon boat song Thirlwell composed was performed at that year’s Dragon Boat Festival, as a tribute to the father of the fishermen, and 37 years later, at the opening of the dragon boat races, they are still singing it.