- The Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, founded 150 years ago, faces questions about the welfare of the animals in its cramped cages

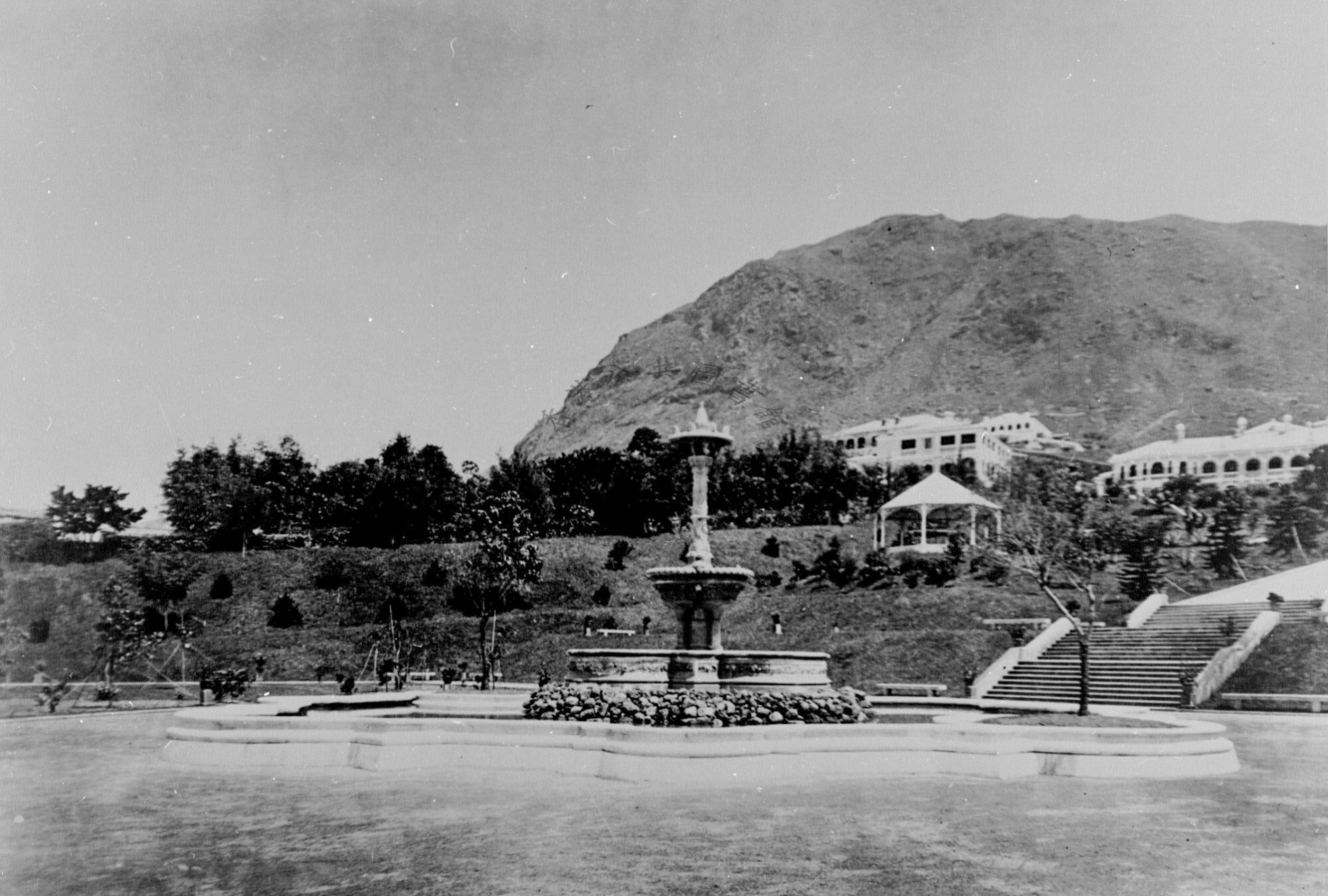

Completed in 1871, the Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens offer a precious green space in one of the densest urbanities on Earth, drawing up to 9,000 visitors per day on weekends, even in the absence of international tourists due to Covid-19 travel restrictions.

“I don’t go there and wouldn’t take my child there either,” says barrister and animal-welfare legislation expert Amanda Whitfort. “It’s an inappropriate place to keep primates, in my view.”

Hers is just one voice in a growing chorus, especially among animal rights groups such as People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (Peta), who say the anniversary should have meant closing the zoo, and relocating the animals to reputable wildlife sanctuaries.

About half of the 5.6-hectare gardens site, managed by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, accommodates some 170 birds, 80 mammals and 20 reptiles, housed in 40 enclosures. And as 2022 begins, looking a lot like 2021, feeling trapped is something that resonates.

“Covid lockdowns and quarantine restrictions have led to a much deeper appreciation of what isolation and lifelong confinement mean for the animals at the Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens,” says Jason Baker, vice-president of Peta Asia. “We have learned so much about animals and their needs over the last 150 years, but the zoo is still operating like it’s the dark ages.”

During a recent guided tour of the gardens, manager Susan Lee Lai-sheung gently deflects criticisms.

“We understand there are many views about the complex issues of keeping animals in zoos but these captive animals could not survive in the wild, we are adding to the gene pool and it is a very small collection,” she says. “We want to inspire the next generation of vets or conservationists and for the young to learn about animal welfare and animal behaviour.”

One visitor viewing the primate enclosures seems to substantiate her view. “I like it, it’s my second visit,” says Dennis, an expatriate from Germany. “It’s not too crowded and my daughter can see animals that she would never normally get to see. I think it’s educational.”

Some enclosures – that house mammals such as Bornean orangutans, De Brazza’s monkeys, buff-cheeked gibbons and cotton-top tamarins – are quite small, and those with steel-mesh walls and concrete floors covered in flaking paint look more like a high-security prison than a wildlife haven.

In one, three common squirrel monkeys share a cage measuring about two by five metres, with little more than a dead tree sprouting from a patch of weeds to distract them from their confinement.

Nearby, siamangs have more space, but one appears languid and a little morose. Known to inhabit the dense foliage in the upper echelons of Indonesian and Malaysian rainforests, one of the primates sits on a narrow log suspended on canvas, strops about five metres above the ground and gazes blankly through the black steel grille of its enclosure. Discarded slices of apple litter the green concrete beneath it.

Lee says the gardens simply do not have the space of somewhere like the Singapore Zoo so they have to be rational: “We are limited in the size we can have our enclosures but we are doing our best.”

The western gardens were opened in 1871 and combined with the eastern area. The entire property was primarily intended as a repository for exotic tropical plants that had commercial value. A few animals were added in ad hoc and as early as 1880 their welfare was a matter of public debate.

“The aviaries and Monkies House are in a very dilapidated state and require thorough repairs or rebuilding,” noted Charles Ford, Superintendent of the Gardens, in his official report published in the China Mail on May 28, 1880. “The Monkies House is in a very bad situation for the welfare of the monkies. In consequence of its shaded position sufficient sunlight cannot be obtained to keep the animals in good health.”

The report also reveals that the gardens were a popular venue for locals that year, with 2,165 visitors on one day alone that March. This, Ford suggested, was evidence that the gardens were “a source of much pleasure”. Wild animals did not feature as the main attraction until much later, and according to government records were interned there “purely for entertainment purposes”.

Ford himself was more enthusiastic about his botanical responsibilities than he was for the creatures in his charge, to which he refers as “a fairly small collection of animals for the amusement and instruction of those people who are fond of such things”.

According to one government memo dated August 1979, Dr K.C. Searle was to be appointed as honorary zoological curator. He was to replace John D. Romer, whose day job was as the government’s senior pest control officer. Romer was also Hong Kong’s first herpetologist, and renowned for the discovery of the Romer’s tree frog in a cave on Lamma Island in 1952.

There is no evidence to suggest the government detected any conflict of interest in Romer being both a zoological curator and a pest control expert.

It was Romer who, in 1976, oversaw the replacement of the resident Asiatic black bear with two young jaguars. He observed that the bear was “a rather lethargic species of bear”, expensive to transport due to its weight, and a “dull exhibit”. It was also Romer who recommended the acceptance of two captive-born orangutans from London Zoo in 1975, on the grounds that they would offer a “major public attraction”, or what zoologists call “charismatic mega-fauna”.

And it is the orangutans that are at the centre of the contemporary row over the quality of animal welfare at the gardens, the validity of conservation efforts, and the need to attract and educate the public.

For the 150th anniversary, I would like to have seen an acceptance that the Hong Kong Zoological and Biological Gardens, without clear conservation or educational objectives, are an archaic conceptAmanda Whitfort, barrister and animal-welfare legislation expert

Recent research suggests that while orangutans are better suited to prolonged captivity than many other large mammals, they are known to become lethargic and obese (another sympathetic aspect made all the more real to humans who have lived through long periods of Covid-19 quarantine recently).

The orangutan enclosures are by far the largest in the grounds, complete with tropical trees and waterfalls, and tower over those of their neighbours like penthouse suites. A planned extension will introduce a common playroom to enhance the enrichment and stimulation of the animals.

“Because of the size of the orangutan, we don’t plan to breed many here,” says Lee, “so if we can help with the global sustainability of the species, that is good.” This includes sending one of the Hong Kong orangutans to a new life at Singapore Zoo once Covid-19 travel restrictions allow.

“Most zoos have evolved away from the Victorian caged approach as the public become aware of animal sentience and that animals are conscious and aware of their environment and capable of positive and negative emotion,” says Dr Alan McElligott, associate professor of animal behaviour and welfare at the Jockey Club College of Veterinary Medicine and Life Sciences, at City University of Hong Kong.

McElligott has more than 20 years’ experience of animal welfare issues and insists that, in the case of the gardens’ animals, “releasing these animals into the wild would be really bad for their welfare, it’s not appropriate particularly for those bred in captivity”.

The animals housed at the zoological gardens are protected by the Public Health (Animals and Birds) (Exhibitions) Regulations, Cap 139F of 1973, the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Ordinance, Cap 169 and the Public Health (Animals and Birds) Ordinance, Cap 139. The law focuses solely on the prevention of cruelty and there is nothing to ensure that welfare standards are met for the animals.

“For the 150th anniversary, I would like to have seen an acceptance that the Hong Kong Zoological and Biological Gardens, without clear conservation or educational objectives, are an archaic concept,” says Whitfort.

A bill currently being drafted, supported by herself and others, would impose a legal duty of care on all keepers of animals to provide adequate levels of welfare. “We should be questioning whether it is appropriate in a forward-thinking city to keep a random collection of captive animals with no connection to Hong Kong.”

The zoological gardens are one of some 400 institutional members of the World Association of Zoos and Aquariums (WAZA), an organisation that offers conservation advice and access to stud-book keepers, who carefully collate records of captive species and their genetic sustainability.

“WAZA gives us good tools to scientifically monitor endangered species,” says Lee, insisting that their captive breeding programme contributes to a gene pool of endangered species and is key to their conservation effort.

WAZA has also published a Code of Ethics and Animal Welfare and approved a 2023 WAZA goal for animal welfare evaluation processes. All institutional members, including the Hong Kong Zoological and Botanical Gardens, must comply.

Lee says the gardens’ conservation focus is shifting to smaller and more indigenous species, but admits there is no specific plan in place for achieving this goal. There have been several consultancy studies undertaken at the zoo but they are not in the public domain. And until a comprehensive independent expert assessment of the welfare, conservation and education strategy of the gardens is completed and made public, the row will only continue.

In the meantime, Lee and her team of 48 staff will continue to do their best for the 280 animals in their care.

“Our staff take pride in caring for the animals and insist on enrichment and stimulation,” she says. “We just want the animals to be happy.”