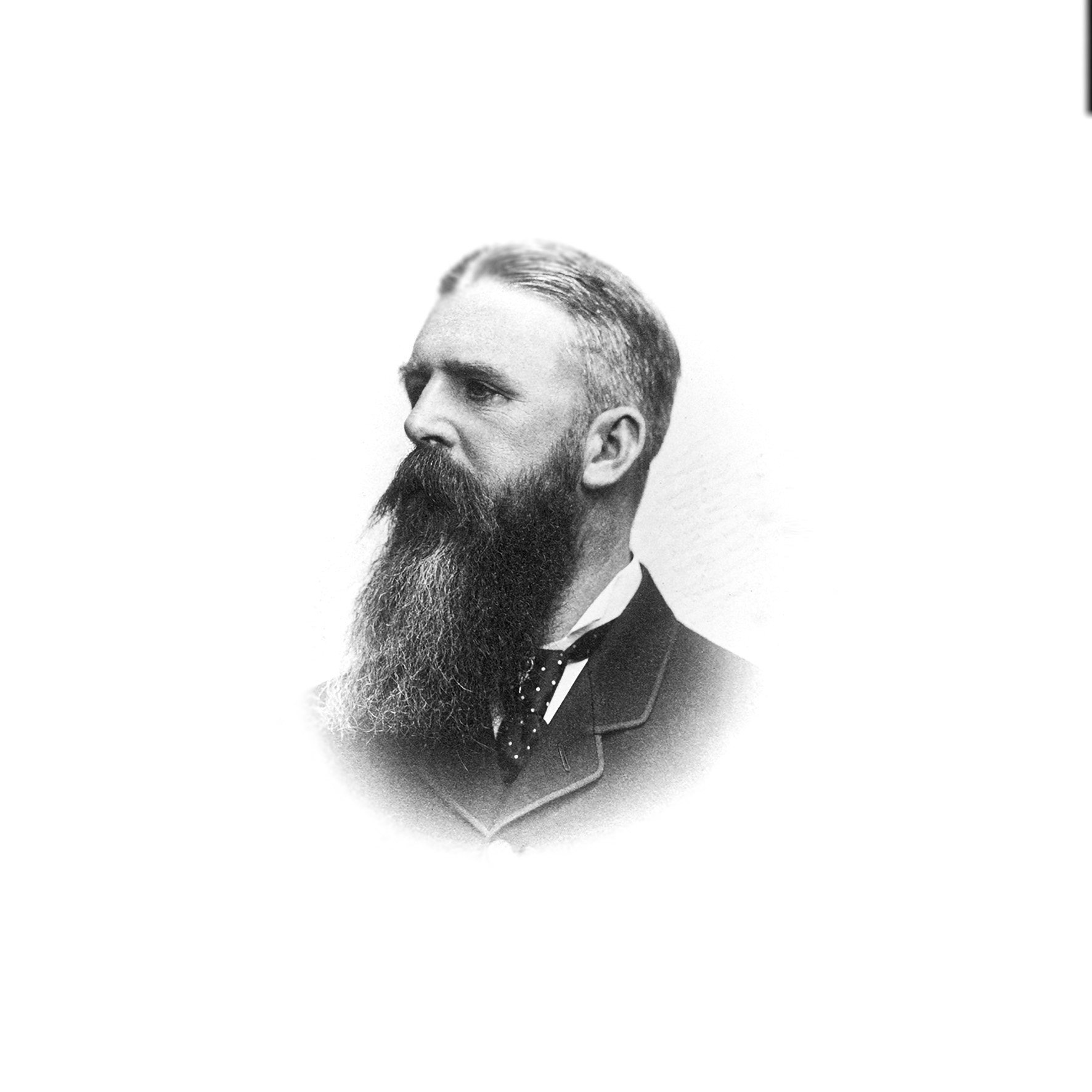

- A Scot, David Marr Henderson spent most of his working life in China, where he built lighthouses that made it into a trading nation. But it wasn’t all work and no play.

Felicity Somers Eve was unaware of her great-grandfather’s achievements until she found a cardboard box in a damp corner of the loft at her mother’s house in 2009. And so from West Sussex, England, thanks to hundreds of objects, photographs, letters, technical drawings and other documents, she pieced together the work of David Marr Henderson and his colourful life, with much of his adulthood spent in China.

Marr Henderson was a controversial, uncompromising civil engineer who worked for the Imperial Maritime Customs Service in Shanghai for nearly 30 years in the late 19th century. He designed and constructed 34 lighthouses across Greater China, most of which, including the Waglan Lighthouse in Hong Kong, still guide vessels from sampans to giant container ships and cruise liners approaching the harbour. His lighthouses connected East and West, his life’s work reflecting an affinity for and sensitivity to the cultural traditions of East Asia.

“My grandmother was born and christened in Shanghai,” says Somers Eve, showing me a photo of her grandmother as a young child, sitting on the knee of her amah. “She used to tell us about it.”

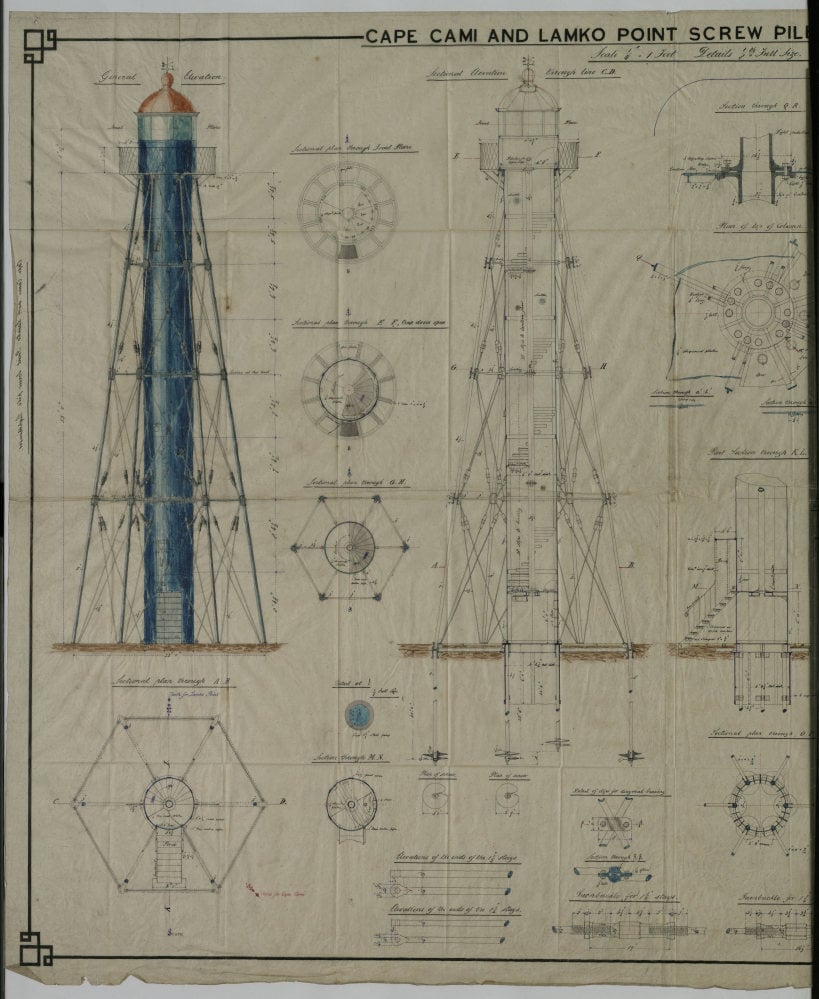

Within a canvas money bag marked “£1000 in sovereigns”, Somers Eve found not gold coins but boxes of drawing instruments with which Marr Henderson created his immaculate scaled drawings of lighthouse designs, now safely stored at the Institution of Civil Engineers archive, in London.

“These are beautiful and rigorous building drawings, showing high-class skill even compared with today’s use of computer software,” says Poon Sun-wah, adjunct professor at the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Architecture.

One of the few Marr Henderson lighthouse drawings seen in public is of Waglan Lighthouse, now a declared a monument in Hong Kong. The drawing was used by student researchers at City University’s Lighthouse Heritage Research Connections group to create 3D printed models of his original design, displayed recently at an exhibition held at the Hong Kong Maritime Museum called “Seeing in the Dark: Stories of Hong Kong Harbour and Lighthouse”.

‘They had no English and no power’: life in London’s Chinatown

Lighthouses’ maritime functions have been diminished by radio navigation, GPS, echo sounders and radar. But for museum director Professor Joost Schokkenbroek “there is a universal and global interest in lighthouses among diverse audiences, they are still seen as beacons of steadfastness, hope and safety whilst also sparking some sort of romance”.

The drawings reflect Marr Henderson’s profound scientific knowledge of optics and the technical skill required to design and construct what is known as a catadioptric light system: reflection techniques via Fresnel lenses (dioptrics) and curved mirrors (catoptrics). The catadioptric mirrors condensed the light from a lamp, often a basic oil burner, about half as bright as a domestic 40-watt light bulb, into a powerful beam of parallel rays, visible to ships up to 22 nautical miles away.

He understood the elaborate clockwork mechanisms for driving the precise rotation of the light and the massive glass lantern that contained and protected the delicate optical apparatus from typhoons. The lighthouse tower, too, had to be designed and secured to withstand the impact of the most violent weather. Even the design and layout of living quarters came in for careful consideration with staff, isolated from the outside world, needing to be self-sufficient in food and drinking water for months on end.

Then there was the daunting challenge of transporting the entire lighthouse in modular form – with its thousands of fragile components, from bearings and lenses to wicks and washers – halfway around the world from factories in Europe, to be assembled on sites selected by Marr Henderson on some of the most remote, inaccessible and often inhospitable promontories, islands and headlands in China.

All of this had to be completed within budget and on schedule, and it required a gifted civil engineer like Marr Henderson, who was not only an adept project manager, but technically skilled over a wide range of disciplines, as well as being practical, resourceful, physically robust and determined.

Hailing from a wealthy Scottish landowning family, Marr Henderson was born near Birmingham, England, on March 9, 1840. Having lost his mother at a young age he was dispatched to a tough disciplinarian boarding school near Falkirk, Scotland, called Blairlodge Academy. It was renowned for its progressive science syllabus, as well as its bullying.

Young Marr Henderson excelled in languages and natural history but grieving for his mother, it is unlikely that this brutal, alien environment did much to enhance his social skills. His school reports describe him as “dour”.

He was apprenticed to his uncle’s civil engineering firm, Fox Henderson, in 1855, while also studying for a diploma in civil engineering at Queen’s College, Birmingham. In 1857, he joined Chance Brothers & Co, the leading British firm in lighthouse design, and was assistant to the company’s senior French engineer, M. Masselin, from 1858 to 1863.

On May 20, 1865, he graduated in civil engineering from Queen’s College, Birmingham. A year later, he was elected as a member of the Institution of Civil Engineers. He was awarded his first patent in 1867. It appeared that Marr Henderson was being groomed to be Britain’s leading lighthouse engineer, until the “knuckle-duster incident” derailed the plan.

The archives of Chance Brothers & Co reveal a bitter dispute between Marr Henderson and an unnamed employee in June 1867 that resulted in an angry and abusive notice being pinned to the front door of its Birmingham factory. A set of knuckle-dusters, owned by Marr Henderson, is retained in the archive, though no one is sure if the two men came to blows. The row was bitter and public enough, however, for Marr Henderson to be dismissed, despite his eminent connections.

Marr Henderson retreated to Paris, the home of lighthouse design, where he studied civil engineering at the École Impériale des Ponts et Chaussées and worked with Chance’s key rival, Barbier & Fenestre.

But it was not all work and no play for the young British engineer: in the West Sussex trove, Somers Eve found a number of exotic postcards sent by young female Parisian stage performers to her apparently popular great-grandfather.

He already was a ladies’ man in Paris. He must have had sexual relations with local womenFelicity Somers Eve, on her great-grandfather David Marr Henderson

Though he returned to Birmingham in the spring of 1868 and obtained work with another engineering firm, PD Bennett, Marr Henderson was no longer considered the golden boy of lighthouse engineering, having earned a reputation for ruffling feathers. A letter dated May 4, 1868, sent by the inspector general of the Imperial Maritime Customs Service in China, Robert Hart, inviting Marr Henderson to become his chief engineer of lighthouses in Shanghai, was well timed.

Marr Henderson accepted Hart’s offer and in November 1868, before leaving for Shanghai via Marseilles, he delivered a lecture to the Institution of Civil Engineers on the state of lighthouse engineering, his swansong to the British engineering elite, an event widely reported in the Shanghai press, who seemed rather shocked to have such a celebrated expert heading to their city.

Marr Henderson was just 28 years old when he arrived in the treaty port of Shanghai in 1869, the so-called Paris of the East. He was on a handsome wage with all expenses paid and already had a well-earned reputation as a womaniser.

“He was a bachelor in Shanghai for 20 years, where there were very few single European women,” says Somers Eve. “He already was a ladies’ man in Paris. He must have had sexual relations with local women.”

Though frowned upon, this was not unusual, and Hart was also widely understood to have a secret Chinese family. Somers Eve’s late uncle, Julian Henderson, spent time in Shanghai in the 1970s, tracing the footsteps of his grandfather. He claimed that Marr Henderson had a Chinese wife and two children before his later, “official” marriage to an Englishwoman, though Marr Henderson took the secret to his grave.

“There, that’s where his brothel was,” says Somers Eve, indicating with her little finger a small, amber-coloured building on a hand-drawn map of the French Concession in Shanghai, dated June 30, 1877.

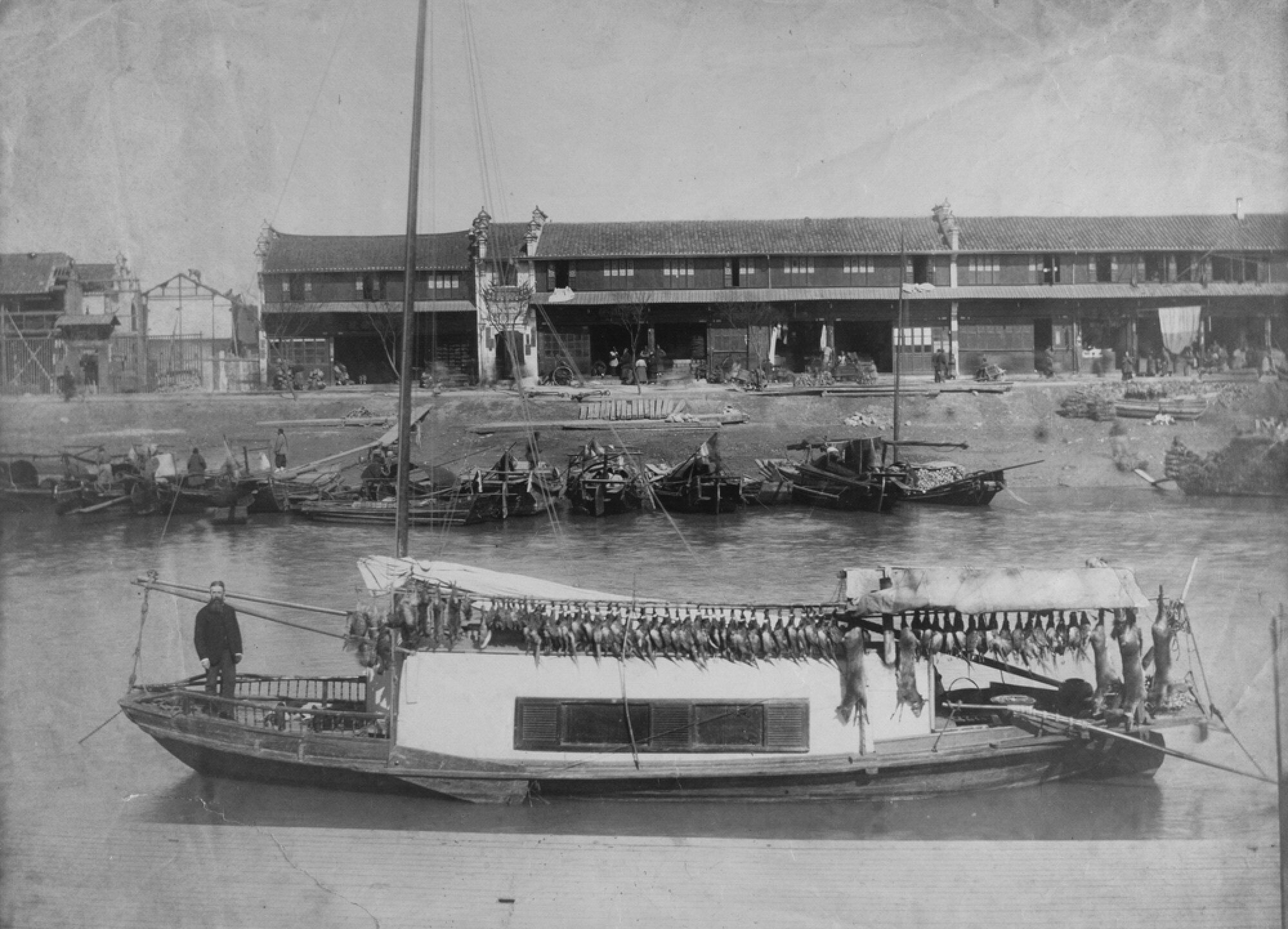

Marr Henderson spoke Chinese, though it is not clear if this was local Shanghainese, formal Mandarin, or both. Either way he always took a translator on official business because of the obscure local dialects in the more remote regions, and his extensive collection of photos reveals a fascination with Chinese culture and architecture.

“He understood and respected the totally different knowledge systems in the East and West,” says Richard Wong Wai-lok, a student researcher into heritage lighthouses at City University, who has become fascinated by Marr Henderson.

Wong points to the English and Chinese versions of the Imperial Maritime Customs’ List of the Chinese Lighthouses, Light-Vessels, Buoys and Beacons, from the 1870s. The English version is in a tabulated format but the Chinese version is written in open paragraphs using traditional Chinese units of measurements. The lighthouse heights are expressed in feet in the English version but as zhang in the Chinese one.

When Somers Eve visited Fisher Island Lighthouse, built by Marr Henderson in 1875, in the Penghu Islands, she learned that he retained the original temple buildings on the site and transferred 12 statues of deities to a nearby Buddhist temple, where they remain today.

Marr Henderson threw himself into his work and, in 1873, won a promotion from Hart, who found him indispensable, but who also had to fend off controversial allegations about him. Hart retained his faith in the man he had appointed, even when Marr Henderson became conspicuously wealthy due to his shrewd investments in local property, including brothels.

Whatever his extracurricular activities, “Henderson is the hardest working and most useful man I know. Pity that people have anything to say against him,” wrote Hart to his London agent on March 21, 1874, alluding to a number of unsubstantiated allegations, accusations and minor scandals that plagued the chief lighthouse engineer.

Marr Henderson was key to Hart’s mission to transform China into an advanced maritime trading nation, and while the work was indeed hard, it could also be dangerous.

The North China Herald dated September 4, 1875, reported that when Marr Henderson visited the Shantung peninsula his small party was “attacked by a mob of villagers armed with hoes, sickles and bamboos with which they inflicted severe cuts and bruises on the unfortunate visitors”.

Visits to Taiwan to build Eluanbi Lighthouse meant avoiding local indigenous tribes who were notoriously hostile to uninvited guests. There was the constant risk of disease and, in April 1882, Hart reported that Marr Henderson was “seriously ill” with typhoid fever, but his star lighthouse builder eventually recovered.

On September 11, 1885, Marr Henderson was conferred with the decoration of The First Class, Third Division of the Imperial Order of the Double Dragon by the Qing Emperor for his exceptional service to the Chinese empire. Somers Eve still has the medal.

In 1889, Marr Henderson became properly respectable upon being wedded to Edith Firmin, 27 years his junior (and several inches taller than he was), in an arranged marriage in England. Returning to the East, the great builder designed and constructed Marr Lodge in Bubbling Well Road, near Shanghai’s famous Bund, for himself and his new wife, and they became popular socialites. Photos reveal a life of horse, dog and poultry shows, tennis parties, shooting expeditions and holidays in Japan. And in November 1891, Marr Henderson became a father at the age of 51, when their only child, Constance, was born.

In the downstairs bathroom of Somers Eve’s house in West Sussex, there is a black-and-white photo of Marr Lodge, dated Christmas 1891. Marr Henderson sits proudly in a deck chair on the expansive front lawn while his wife and new baby daughter gaze down from the distant upstairs veranda. The home was located near what is now the bustling shopping and office district of Shanghai’s Nanjing Road.

Before leaving China for retirement in England, Marr Henderson had time for one last showdown. On this occasion it involved his boss, the universally admired Robert Hart, which seemed somewhat incongruous given that Hart had been a supporter and defender of Marr Henderson. A letter dated January 11, 1898, contains a detailed claim, addressed personally to Hart from Marr Henderson, demanding remuneration for underpayment. Another letter, dated the same day and in the same tabular style, details underpayments into pension provision. The combined total of the claim, including compound interest calculated at 7 per cent, was in excess of £37,000, more than HK$50 million in today’s money.

Marr Henderson had worked for Hart for almost 30 years, yet there is no warmth in his letters. The engineer won his case and returned to England in 1898 a wealthy man. Somers Eve suspects the pension dispute was triggered by the need to ensure that his “undocumented” Chinese family was adequately provided for. And on his death in Hove, England, on September 18, 1923, Marr Henderson left considerable sums in his will to women not known to his family.

Historian Robert Bickers, who helped to digitise much of the Marr Henderson archive, notes that while the age of the lighthouse as a travel necessity has long since passed, “It is worth pausing to consider how men like Henderson made significant contributions to the integration of China into global shipping networks, and the global economy”.