China’s competing legacies on show at National Palace Museums in Beijing and Taipei

- The mid-century scramble to stop priceless art and artefacts falling into the wrong hands saw country’s collection of imperial artefacts splinter

- Nationalists transported their treasures to Taiwan, while newly minted People’s Republic allowed Forbidden City to preserve posterity

Two faces press against a glass case, mobile phones raised. The object of their interest looks like a single succulent piece of braised pork purloined from the museum cafe downstairs. Closer inspection reveals it to be a delicately carved lump of stone. Nearby resides an almost perfect stalk of bok choy (complete with a pair of insect stowaways) made of jadeite.

These two objects are among the most sought-out artefacts on display at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. While perhaps not as valuable or artistically important as other pieces in the collection, each is a perfect blend of whimsy and craftsmanship. The “meat-shaped stone” and “jade cabbage” are just two of 1,700 pieces on display, each one selected for removal from mainland China as the government of Chiang Kai-shek relocated to Taiwan in 1949.

How China’s Forbidden City became the Palace Museum

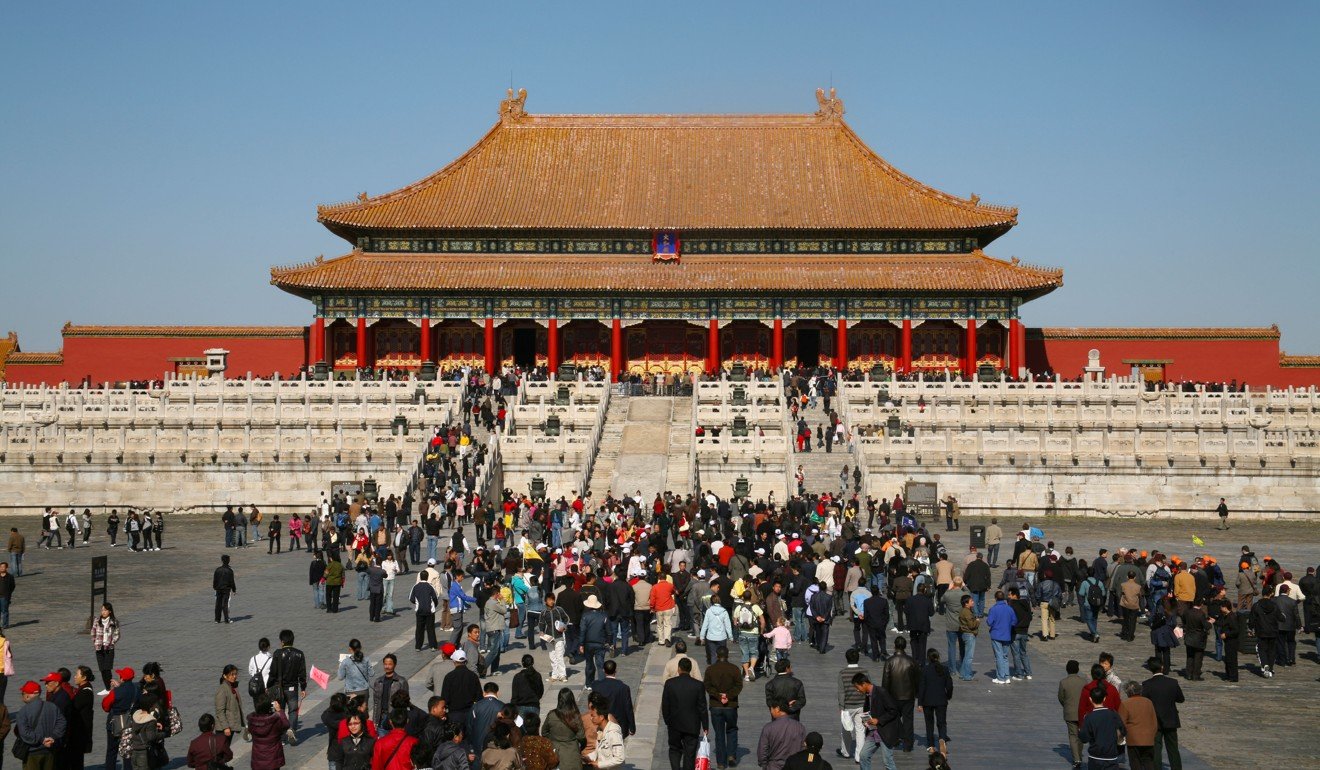

More than 1,800km away, at the other National Palace Museum, in Beijing, a mother vainly tries to make space for her young son in a heaving scrum outside the Palace of Supreme Harmony. Once the main ceremonial hall for the 24 emperors of the Ming and Qing dynasties, who ruled from the Forbidden City, today the hall is near empty.

It is an impressive building – at more than 2,300 square metres it is perhaps the largest wooden structure in China, with a floor made of “golden bricks”. These are named not for the material of which they are made but for the expensive and time-consuming process of firing and re-firing they underwent, such that each was said to be worth its weight in gold. But aside from the crowds, the place has something of an air of barren lifelessness.

A throne – but not the throne of the emperors, which was removed and then lost in the early 20th century – sits in pride of place at the centre of the cavernous room. The objets d’art and ritual vessels are gone and few treasures are on display. Visitors must peer into the space and use their imaginations – or recollections from the most recently streamed Qing dynasty costume drama – to recreate the material culture of the imperial realm.

Now both museums are facing major change. The Forbidden City is in the midst of a 10-year project to renovate and open more than 95 per cent of the palace to the public by 2025, the centennial of the Palace Museum in Beijing. The Taipei museum, which shares a pre-1949 history with its Beijing counterpart, will close most of its exhibition spaces for a three-year overhaul beginning in 2020.

The abdication document was less clear about what would happen to the vast numbers of antiquities, art pieces and imperial knick-knacks collected by Puyi’s predecessors. This massive trove of cultural treasures was spread over many locations, including the Forbidden City, the Imperial Hunting Lodge, in Chengde, just north of the Great Wall, and the rebuilt Summer Palace, outside Beijing. Nobody seemed to know what was stored where.

When items from the imperial collection started turning up in antique stores in the capital, the Republican government knew it needed to prevent pieces from falling into the hands of private collectors and overseas museums.

In December 1913, the Gallery of Antiquities opened in the Hall of Martial Valor, in the southwestern corner of the Forbidden City. A subsequent agreement struck with the rump imperial court, languishing in the northern part of the same palace, gave the Republican government the right to purchase pieces from the imperial collection and exhibit them in the gallery. Crates soon started arriving in the Forbidden City laden with artefacts from as far away as the palace of the Qing emperors in Shenyang, Liaoning province. Beijing residents queued up to pay the equivalent of a city worker’s monthly salary for a glimpse of the art and artefacts of the deposed imperial clan.

But were the objects on display national treasures or imperial heirlooms?

The government’s problem, as was often the case in the early years of the Republic of China, was cash. It didn’t have the funds to cover the cost of all the antiquities being added to its new gallery, and so many of the items were technically “on loan”. Equally unsustainable were the lavish stipends promised to the emperor and his family. This collision of ambiguous ownership of antiques and the financial insolvency of the imperial clan triggered a spate of thievery and appropriation.

Puyi’s tutor, Sir Reginald Johnston, had his suspicions. In his memoir, Johnston noted drolly that the unreliable government stipend seemed hardly sufficient for his student’s opulent lifestyle and that the all too obvious practice of making up the shortfall by mortgaging or selling palace treasures left much to be desired.

The young emperor and his advisers were quick to point fingers at corrupt officials in the household administration and the hundreds of eunuch servants still employed by the palace. Having sacrificed much to join a suddenly ex-emperor’s service, it’s perhaps hard to blame the eunuch staff for their sticky fingers.

In his autobiography, Puyi writes: “From my tutors, I learned the treasures of the Ch’ing House were known throughout the world and that the amount and value of the antiques, the calligraphy and paintings were tremendous […] But since most of the items were uncatalogued it was impossible to tell if anything was missing. This made it easy for thieves.”

Suspicious that others shared his penchant for larceny, Puyi requested an inventory of the remaining items held in storage at the Jianfu Gong (the Palace of Established Happiness), in the northwestern corner of the Forbidden City. It never arrived. On June 26, 1923, the palace burned to the ground under suspicious circumstances. Only 400 or so of the artefacts housed within survived.

Following standard palace protocol (when in doubt, blame the eunuchs), Puyi ordered the expulsion of the 1,000 or so remaining castrated male servants. The remains of the palace were demolished and a tennis court was built in its place. (The Jianfu Gong would be rebuilt in the 1990s and it served as the site of the dinner between Donald Trump and Xi Jinping when the United States president visited Beijing in 2016.)

Puyi was soon to follow his servants out of the palace gates. In 1924, the young former monarch, his wives and retinue were unceremoniously evicted from the Forbidden City on the orders of warlord Feng Yuxiang.

Following Puyi’s departure, the Inner Court in the northern precincts of the Forbidden City opened for the first time with plans for the space to be turned into something more than just a gallery. Early curators looked to other palaces-turned-museums, such as the Potsdam Palace, in Germany, the Hermitage, in Russia and the Louvre, in France, for inspiration as they planned a new national museum, while scholars such as Yi Peiji and art historian Li Yuying oversaw the cataloguing of what remained of the palace collection. It was a monumental task performed with care and under high security. Curators required at least three people to be present at all times during cataloguing to prevent staff from pocketing heirlooms.

Surprisingly, despite rampant looting by foreign powers during the 1860 and 1900 occupations of Beijing and the subsequent dispersal of items by eunuchs and the cash-strapped imperial court, the final inventory ran to 28 volumes and included more than 1.7 million items.

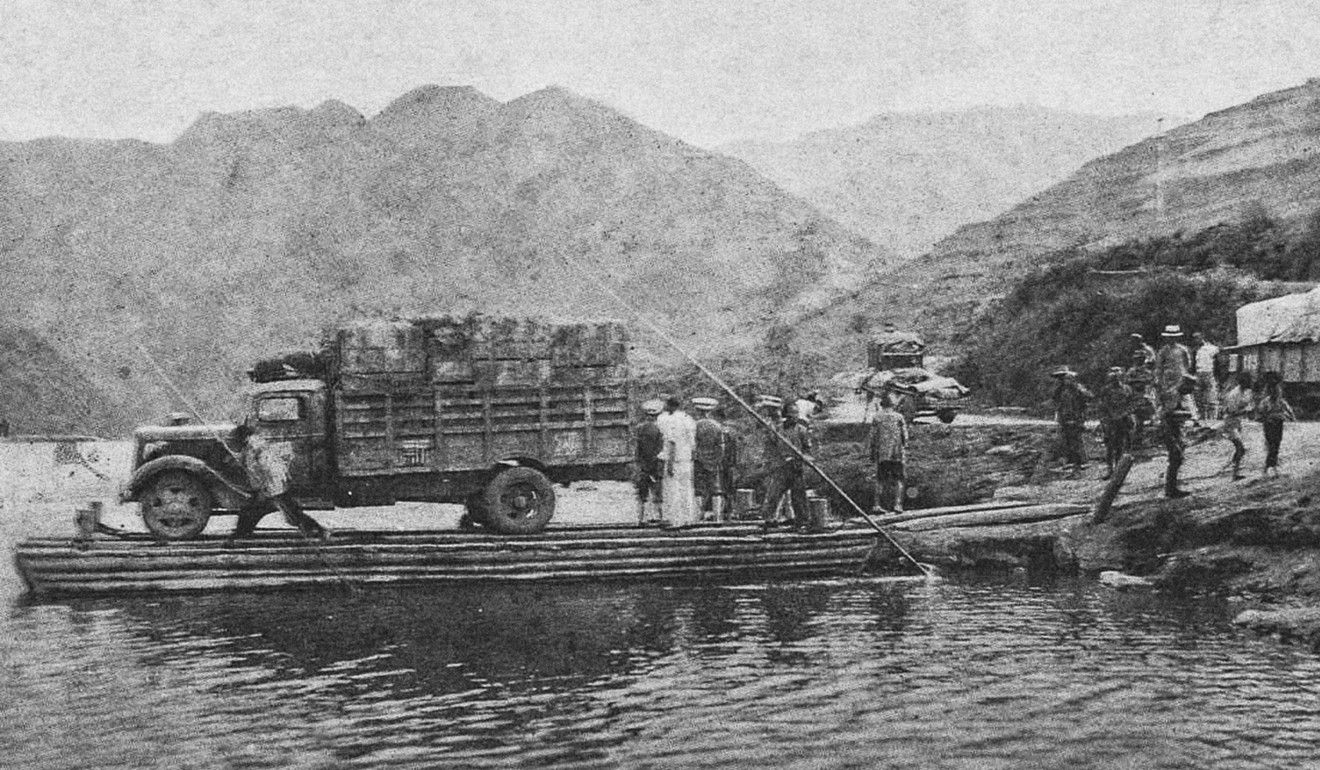

By 1931, the Japanese were making inroads into Manchuria and threatening the security of China’s former imperial capital. The government responded by ordering that the most valuable artefacts in the Palace Museum collection be crated and moved out of Beijing. Nearly 20,000 crates of artefacts were boxed up and shipped south. It was an enormous undertaking demanding the utmost discretion of museum staff; residents might see the removal of imperial treasures as a signal the government had abandoned hope of defending their city.

The artefacts made their way to Shanghai, where the presence of the international settlements promised a measure of protection, before the government moved the crates again, this time to the capital at Nanjing. Plans to begin constructing a vault and museum for the collection in the summer of 1937 were abandoned as war spread throughout China. The 20,000 crates moved once again, this time upriver to Changsha and Hankou, before landing in Chongqing, destined to become the wartime capital of Chiang Kai-shek’s government.

Complicating matters was the return of Puyi to the political stage in 1932, this time as the titular head of Manchukuo, a puppet state Japanese forces had carved out of northeastern China. Before his eviction, Puyi and his brothers had diligently smuggled scroll paintings and other easily stashed items out of the palace. Puyi was reunited with his treasures during his exile in Tianjin, once again selling select items to collectors and scholars to finance his lifestyle in the port city. With Puyi’s “restoration”, his small hoard of imperial baubles and art followed him north to his new capital at Mukden (Shenyang).

As the fortunes of war turned against Chiang Kai-shek, his government prepared for a retreat to the island of Taiwan. Selected from what remained of the 20,000 or more that had left Beijing, containing more than 600,000 items, 3,824 crates crossed the strait in 1948 and 1949. The remaining crates sat in Nanjing for months until the new government of the People’s Republic of China arranged for their return to Beijing. There they languished, in the dusty halls of the increasingly decrepit Forbidden City.

The loot taken to Taiwan fared little better. The crates evacuated from the mainland were stored in a tunnel complex dug out of hillsides not far from the central city of Taichung. The caves offered protection in the (at the time seemingly likely) event of an attempt by Beijing to retake the island, but the facilities were poorly designed for preserving priceless antiquities. Frequent floods, vermin and humidity took their toll on books and scrolls. Moreover, the collection was for the most part inaccessible to all but a few privileged scholars and officials.

Back in Beijing, the Palace Museum was facing an existential threat of its own. The city was once again the capital, and the new leaders occupied the former imperial park of Zhongnanhai, just across the street from the Forbidden City. Despite being a neighbour, Mao Zedong reportedly never set foot in the Forbidden City after 1949. It’s not known whether this was out of ideological purity, revolutionary optics or pure superstition. The closest Mao ever came was when he strolled along the high red walls that surrounded the palace.

Mao and his government faced the question of what to do with an enormous – and now unoccupied – imperial palace sitting right in the heart of the new socialist capital. As early as the 1920s, left-wing scholars had called for the palace to be dismantled and its collection sold for the benefit of the national treasury. In the 1930s, the palace had escaped having its imperial yellow rooftops repainted Kuomintang blue.

Mao set out a bold vision to transform the old imperial capital into a production hub, with smoke stacks rising as far as the eye could see. A proposal to preserve the historic architecture of the city and build a new administrative capital to the west of the city walls was shelved as centuries-old gates and arches came down. Streets were widened, temples transformed into workspaces and courtyards became horizontal tenements in an increasingly crowded capital.

The new government at first sought to draft the Forbidden City into revolutionary service. The ceremonial halls along the central axis were reopened and housed temporary exhibits extolling the new society while mocking China’s imperial past. On two occasions, the Beijing municipal government discussed plans to build an east-west highway through the centre of the Forbidden City. The palace was spared as the proposal fell victim to the political and economic turmoil that characterised the Mao era.

The late 1960s and early 70s mark the beginning of the modern history of both the Taipei and Beijing Palace Museums. The Forbidden City and the Palace Museum in Beijing were closed during the Cultural Revolution, sparing them from destruction at the hands of the Red Guards. (Frustrated in their attempts to break through the back gate and pillage the palace, groups of young people instead settled for hanging a sign over the high wooden doors reading “The Palace of Blood and Tears”.)

The palace would remain sealed to the outside world until July 1971. A visitor from America, Henry Kissinger, in Beijing for secret talks with premier Zhou Enlai that would eventually lead to Richard Nixon’s historic 1972 visit to China, was taken on a personal tour of the palace by his host. In preparation for the US president’s arrival, the staff set about repairing a palace suffering from nearly six years of not-so-benign neglect. Nixon’s visit to the palace was one of the highlights of a trip that signalled a new era in US-Sino relations and China’s openness to the world.

The resilient former palace became a strategic asset and beginning in 1974, the government unveiled a plan to develop the Forbidden City for international visitors. Over the next decade, world leaders including US president Gerald Ford, Britain’s Margaret Thatcher and Queen Elizabeth, and Singapore’s Lee Kuan Yew toured the Forbidden City during visits to Beijing.

The US also had a hand in the construction and opening of the rival National Palace Museum in Taipei. With crates of treasures slowly deteriorating in rotten containers following their evacuation from the mainland in 1948-1949, scholars and politicians in Taipei began calling for the building of a permanent home for the collection. A site was chosen in a northern suburb of Taipei, at the base of a ring of mountains. The location boasted excellent feng shui, but its proximity to Chiang Kai-shek’s suburban retreat at Shilin may have had something to do with the decision.

The new building would pay respect to Chinese tradition while incorporating modern features necessary to preserve the treasures inside. These included underground tunnels and bunkers for storage designed to protect artefacts from humidity, insects, typhoons, earthquakes, air raids and other potential disasters.

The project foundered for lack of funds, until the US stepped in and agreed to match contributions by the Taipei government. Finally, on November 12, 1965, on what would have been the 99th birthday of Kuomintang founder Sun Yat-sen, the museum opened its doors to the public. Thousands of visitors flocked to its four storeys to marvel at works of art that had been hidden from view, in some cases, for more than 30 years. But the crowds soon overwhelmed the space. The new museum may have boasted 7,000 square metres of floor space, but that was still less than 1 per cent of the Forbidden City’s epic sprawl.

It was evident that in the divorce, the Taipei museum may have grabbed all the best pieces, but it was Beijing that kept the house.

The two museums represent competing legacies. As Beijing moves beyond the ideological blinkers of Marxism and class struggle, there is a growing need to tie the legitimacy of the state to the perpetuation and preservation of China’s past. For Taipei, the National Palace Museum demonstrates Taiwan’s long-standing effort to protect and maintain Chinese tradition.

In the 60s and 70s, the rampages of the Cultural Revolution, which consumed irreplaceable artefacts and art throughout China, justified the existence of a museum in exile. Today, it is an important symbol of a history shared on both sides of the strait, one not always in keeping with the goals of some in Taiwan to explore and celebrate a distinctively Taiwanese identity.

In Beijing, the Forbidden City is undergoing something of a renaissance. Television series including the wildly popular National Treasure and a new reality show being streamed on iQiyi are making imperial history accessible to a younger audience. Museum curator Shan Jixiang brags that the Palace Museum now offers more than 8,700 palace-themed products in its gift shops and online with sales of merchandise last year alone topping 1 billion yuan (HK$1.16 billion).

New cafes and restaurants are opening throughout the Forbidden City. More than a decade after US coffee giant Starbucks was given the boot, domestic rival Luckin set up inside the palace. New branches of the museum are planned for northern Beijing and West Kowloon, in Hong Kong.

As part of its centennial campaign, new areas are being opened to the public. Starting last October, visitors could for the first time walk along the eastern palace walls from the front to the back gates (although the western palace walls with their clear view across the street into Zhongnanhai remain firmly out of bounds).

Back in Taipei, the galleries are full but not to the extent of the heaving human scrum that packs exhibit spaces during peak times at the Forbidden City. The National Palace Museum in Taipei hosted 4.4 million visitors last year. That’s down a little from a few years ago and is just one quarter of the more than 16 million tourists who tramped through the Forbidden City in 2017.

Meanwhile, to improve cultural equity between northern and southern Taiwan, the Southern Branch of the National Palace Museum was opened in Taibao, Chiayi County, in 2015, at a cost of NT$7.93 billion (US$258 million). With a target of 1 million visitors annually, it was reported to have attracted a disappointing 800,000 in 2018.

It remains to be seen whether the proposed three-year renovations in Taipei will attract more visitors or whether Beijing’s ambitious plans to transform the Forbidden City into a world-class destination will succeed.

Seven decades on, the division of China’s imperial treasures remains, with no end in sight.

Jeremiah Jenne is a writer and history teacher based in Beijing.