Hong Kong publisher releases last of Chinese zodiac-themed children’s books – in time for Year of the Pig

- With Ping Pong Pig, Sarah Brennan, a Hong Kong author and small publisher, completes a charming series of children’s books with a Chinese twist

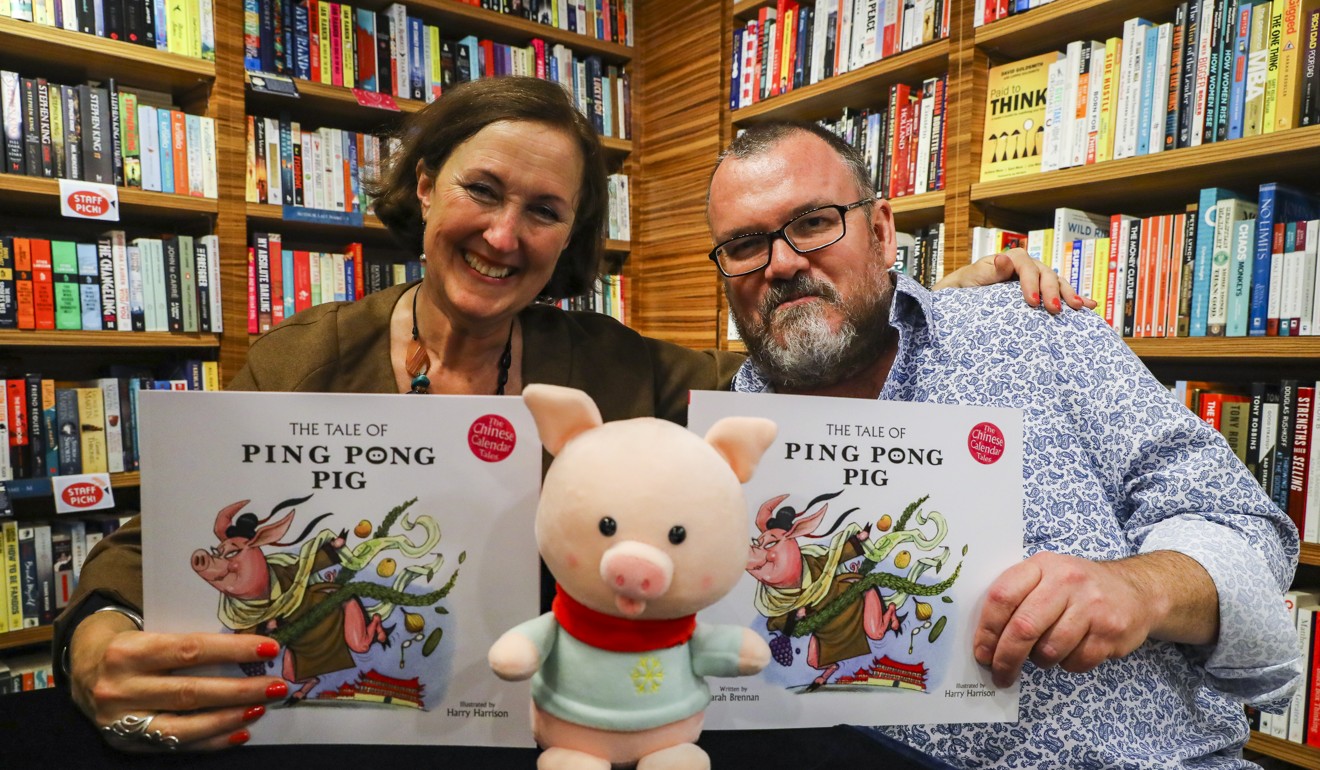

- The books are illustrated by the Post’s Harry Harrison

Should she ever decide to write her own tale, it would surely star Single-minded Sarah. For Brennan, the concept of the half-measure is an alien one. Her press release to Post Magazine about Ping Pong’s debut stated unequivocally: Important Hong Kong publishing phenomenon. Her blog is peppered with exclamation marks and fabulous doings. These merely hint at the full-on, indefatigable personality.

“I discovered I had a head for PR!” she says, cheerfully, one recent morning in a small Fo Tan industrial space crammed with boxes of books. “I love talking to the press. I love meeting the customers! If you want to publish for yourself, you have to be able to self-promote. I do remember – it was pretty horrifying – when an agent in London said to me, ‘Thank goodness you’re reasonable-looking because otherwise we wouldn’t be able to take you on.’ You can’t be a shy, wilting author any more!”

Crouched on the floor behind us, Annabel – one of Brennan’s two daughters – and Annabel’s friend, Leah, are assembling boxed sets of the Chinese Calendar Tales. Now that the zodiac’s dozen animals have been completed, a new sales opportunity has presented itself. Brennan examines one set, checking all 12 spines are exactly aligned to create the red dragon that is her business logo.

“Printers’ tolerance,” she explains of the slight variations that printers permit themselves but which can make a perfectionist publisher’s life difficult. As we’re talking, she produces a black felt-tip pen and begins applying it to her leg so it looks, for a confused moment, as if she’s editing herself. In fact she’s disguising pale spots on her dark leggings, a result of bleach-splashes from the industrial-level cleaning she did in preparation for this interview. When you’re a small publisher in Hong Kong, you have to turn your hand to all sorts of things.

“I’m a Rat,” she says. “Driven. Ambitious. Have to keep moving. If I’ve got nothing to do, if I’m at an impasse, I can get really ratty. The thing I’ve found in this business is that if one door closes you make another door open. You have got to go on and on and on.”

Auspicious Snow

Only when she was filling in the registration form in 2003 at Revenue Tower did she realise she’d have to call it something. “Holy moly! I hadn’t a clue,” she says. The painting, however, came to mind. “I love the word ‘auspicious’. And I was going to do articles in the South China Morning Post” – she waves a hand at the tape recorder – “I was going to do all of this and so I thought of ‘times’, like newspapers.”

Just so. And that, dear reader, is how Auspicious Times got its name. She agrees it’s been lucky for her. The only downside is when busy book-buying parents occasionally make out cheques to Suspicious Times. Then the bank sends them back, which isn’t ideal for the cash-flow.

Despite her love of talking to the press, Brennan is reticent about certain aspects of her professional life. She won’t tell me, for instance, the square footage in Fo Tan or the number of books the space contains – “so my competitors are none the wiser,” she writes, later, in an email. Nor does she wish the painter of Auspicious Snow to be identified, which seems overly scrupulous as it’s not a household name. But perhaps these are suspicious times.

On the other hand, her natural effusiveness means she can be unexpectedly frank. When I ask if she’s making money, she says, “We’re making money to keep the company afloat, to keep new projects going and to put some aside. But I’m not putting food on the table. If I had to put food on the table and pay school fees, I wouldn’t be in this business. You can’t.”

The person who does supply the food is her second husband, Philippe Gonnet, who is French and works here for, appropriately enough, the European grocery company Lidl. They met a month before her decree absolute came through and were married in December 2006. Astrologically, Philippe’s a Pig; Ping Pong Pig’s adventures are dedicated to his perfect porcine patience in waiting so long for his own zodiac tale.

Brennan believes they bonded over bagpipes, which she can play and which her husband has loved since he was 12. “We’re twin-souls,” she states. “A boy from Paris meets a girl from Tassie and we have everything in common.” (She sometimes gives the impression that she’s blurbing her own life, an occupational hazard.)

“Tassie” is Tasmania, in Australia, where Brennan, who has a twin sister, grew up on the slopes of Mount Wellington. Her father was a doctor; her maternal grandfather was Sir Eric Harrison, one of the founders of Australia’s Liberal Party and the man in charge of Queen Elizabeth’s official tour in 1954. As described in her blog, it was an Enid Blyton childhood with peacocks, goats, blackberry bushes, a creek – even a platypus that only she saw so no one quite believed it existed.

When I ask if the platypus was real, however, she replies, “After the 1967 fires ripped through the whole thing, the bank was laid bare and there were the tunnels”. Those bush fires, which killed 62 people and made thousands homeless, remain Tasmania’s worst natural disaster. Brennan’s father was in Melbourne at the time and the family car was being serviced down in Hobart. She supplies a vivid vignette: her mother, in a swimming-costume, filling roof-gutters with water and tennis balls (as plugs), watched by four children below the age of eight while the fires skipped from hill to hill. The house survived; those around, she says, did not.

Organisational skills are clearly in the maternal genes. Is she like her mother? “Mum was phenomenal, practical. Dad was a bit of a dreamer, an Irish poet. Mum had to cope.” So half and half? “Yes.” Earlier she said, “I think I’m centre-brained, I really do. I am very creative but I’m not pure artist.”

In that year of the fires, Brennan turned seven. As she frequently tells her young fans, her writing life began at seven and pop-psychology might suggest a link. She says not, that she’d started writing poems at school, enjoyed the process and kept going. Although she qualified as a lawyer in Queensland, her heart doesn’t seem to have been in it. Or, as she puts it, “I went to work at the tax office because I wanted to be an actress.” (The hours were flexible.)

As a result of what she calls “a very unfortunate series of events with a car accident” – she lost a court case and had to pay all costs – she was obliged to take on a second job, not as an actress but a waitress. Eventually, at 28, having saved A$2,000, she travelled through Europe and arrived in London, where, after a succession of random jobs, she returned to legal practice and got married. In 1997, she had her first daughter, Beatrice; the family moved to Hong Kong a year later.

Annabel was born in 2000, and it was the Pre-Schools Playgroup Association, on Borrett Road, that prompted the move into publishing. In 2003, Brennan was asked to write something for the in-house magazine, which had just been bought by P3 Publishing and would become better-known as Playtimes. She became a columnist and David Tait, P3’s managing director, asked her to write a poem for a Robert Burns evening. Naturally, she drew on her bagpipe experience.

“I declaimed it, everyone started clapping and the next day he was on my doorstep asking if I’d got anything else for kids. I said, ‘Where do you want to start?’ I had a bag full of stuff. He picked out A Dirty Story and said, ‘I think I know someone who’d like to illustrate this.’”

By then, Brennan was hoofing around schools, selling the product. “The majority of the kids are Chinese, and I thought, ‘If I were a Chinese kid, I’d be sick to death of having Western style [stories] rammed down my throat when I’m learning English.’ I thought it would be really great to do something about Chinese culture and be fun.”

She’d already written a story that began: “There was a Chinese dragon/His name was Chester Choi/ When Chester Choi grew hungry/He’d eat a little boy. ” While renegotiating her status with the Immigration Department, the man assigned to deal with her was called Chester. “Actually, I think he was a Chester Choi!” (I ask Harrison about this improbability later and he says, yes, he remembers Brennan saying something about it at the time.)

Both Chesters brought her luck. Chester-the-immigration-officer listened while she span him a fairy-tale. “I lied through my teeth, absolute whoppers. I showed him a business plan where, you know, within two years I’d be employing six people. All I had was a contract for A Dirty Story.” He could have devoured the dream on the spot. Instead, he granted her a year’s stay and, a year later, another. By then, she’d qualified for permanent residency.

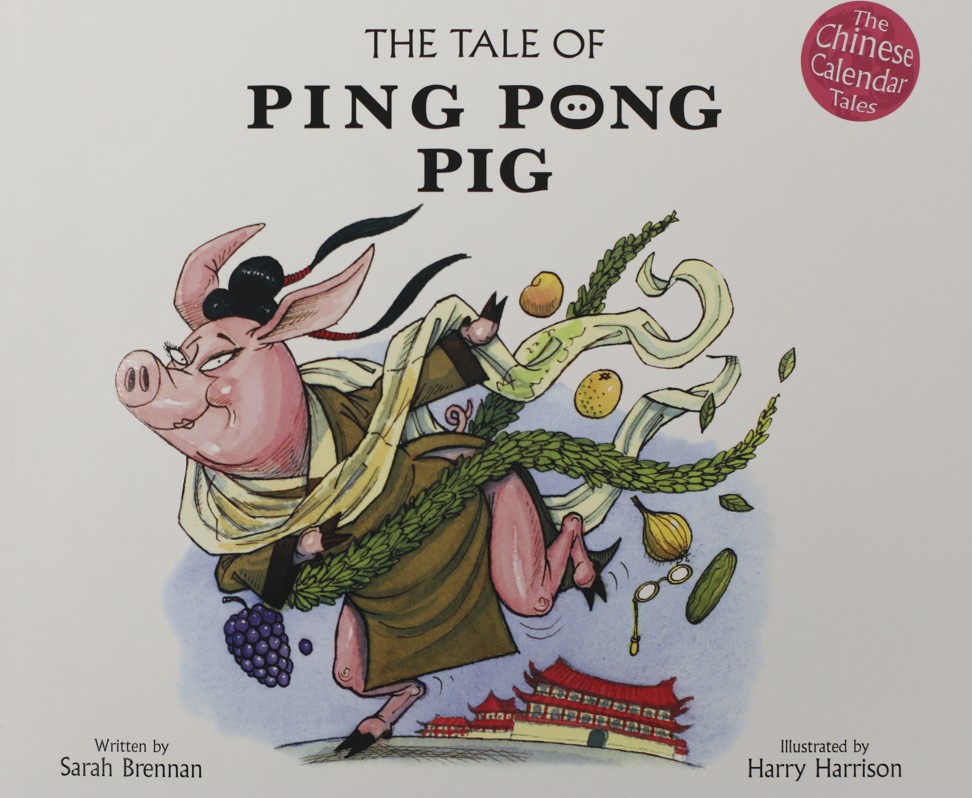

Similar fortune smiled on Chester-the-dragon, subject of her first self-publication. She took a dummy-copy round schools “on a wing and a prayer”, telling the children that if they bought it, she could afford to print it. “I’d not thought of Chinese New Year, the zodiac, nothing like that,” she says. It was 2007, a Pig year, and the book came out in the autumn.

But 2008 was the Year of the Rat, the beginning of the next zodiac cycle. It was also the year of the Beijing Summer Olympics. In May, The Tale of Run Run Rat appeared and, soon afterwards, Time Out Hong Kong published a list of the city’s English-language bestsellers. Number one was Run Run Rat. Number two was Chester Choi. Also-rans J.K. Rowling and Stephenie “Twilight” Meyer trailed in third and fourth, respectively. Brennan framed the list and hung it in her bathroom.

Brennan has a 1pm reading followed by two workshops at Stamford American School, in Ho Man Tin, for which she is a “global mentor”. Out on the street, she explains the basic economics of self-publishing. Sixty per cent goes to distributors, with the remaining 40 per cent going on printing costs, the office, the illustrator’s fee, transport, etc. As an author, she receives royalties of 7 per cent but she doesn’t pay herself any money. Getting into her 22-year-old Mazda, she remarks, “When you’re a publisher, you drive the oldest car in Hong Kong.”

For years publishing house Macmillan did her printing. It had a joint venture in China and Brennan was optimistic her books would sell on the mainland. Around the time of her separation, she visited Betty Palko, a medium usually described as “Diana’s psychic” who, despite failing to warn the Princess of Wales to wear a seat belt, used to have a devoted following in Hong Kong.

“She said, ‘You have a guardian angel, he’s standing behind you – an old Chinese gentleman,’” says Brennan. (This may have been Lin Foo, a dead Chinese philosopher whom Palko would occasionally refer to in interviews as one of her spirit-visitors.) “Whenever I go into China, I get a frisson. And I wonder if I wasn’t Chinese in a previous life, quite seriously. Because I. Just. Love. China. There’s something about it that makes me tingle.”

SCMP cartoonist Harry celebrates 20 years in Hong Kong with a look back at his favourite work

Unfortunately, however, Macmillan’s Chinese partner said no to the books for a fundamental reason: it didn’t love the look of them. “Basically, Chinese mums and dads like Hello Kitty. So Harry’s style, which is absolutely superb and such fun, is not the style for China, it really isn’t. It’s too sardonic. In China, they consider one of Harry’s screaming ladies not funny but ugly.” (“I agree,” says Harrison, whose artistic hero is Ronald Searle. “My style’s British and not pretty enough.”)

In any case, Macmillan dropped its small publishers when it merged with American publishing company Springer in 2015. You can’t help wondering why anyone would continue but, in the car, Brennan, like Lin Foo, waxes philosophical. “Basically, this job is its own reward. It’s utterly fulfilling. It. Makes. Me. Happy.”

The school takes a while to find as Brennan holy-molys round the streets, arguing with the GPS. (“It thinks we’re men! North, south, east, west – we don’t do that. We were round the campfire, socialising.”) Inside, Lisa Olinski, the school’s senior marketing and communications manager, tells Brennan that because of the ’flu epidemic, most of the invited kindergartens have cried off.

Eventually, about a dozen children, a third of them in face masks, file in with assorted helpers and parents. Some of them are well below reading-age but Brennan gives no indication this isn’t an ideal audience. Decades after the tax office, she has her acting career after all. “Are you all here?” she beams. “Can you giggle if you’re not?” As Harrison’s wonderful illustrations appear on a screen, she starts The Tale of Chester Choi as excitedly as if the ink had just dried on it. A ripple of laughter warms the room.

Later, about 40 children attend a storytelling session; 25 go to the writing workshop. Stamford is only one of several school visits Brennan does during the week. When I ask her how many books she’s sold since 2007, she guesstimates 80,000 “which is good for a small publisher”. This is how she does it, pebble by pebble, building the mountain.

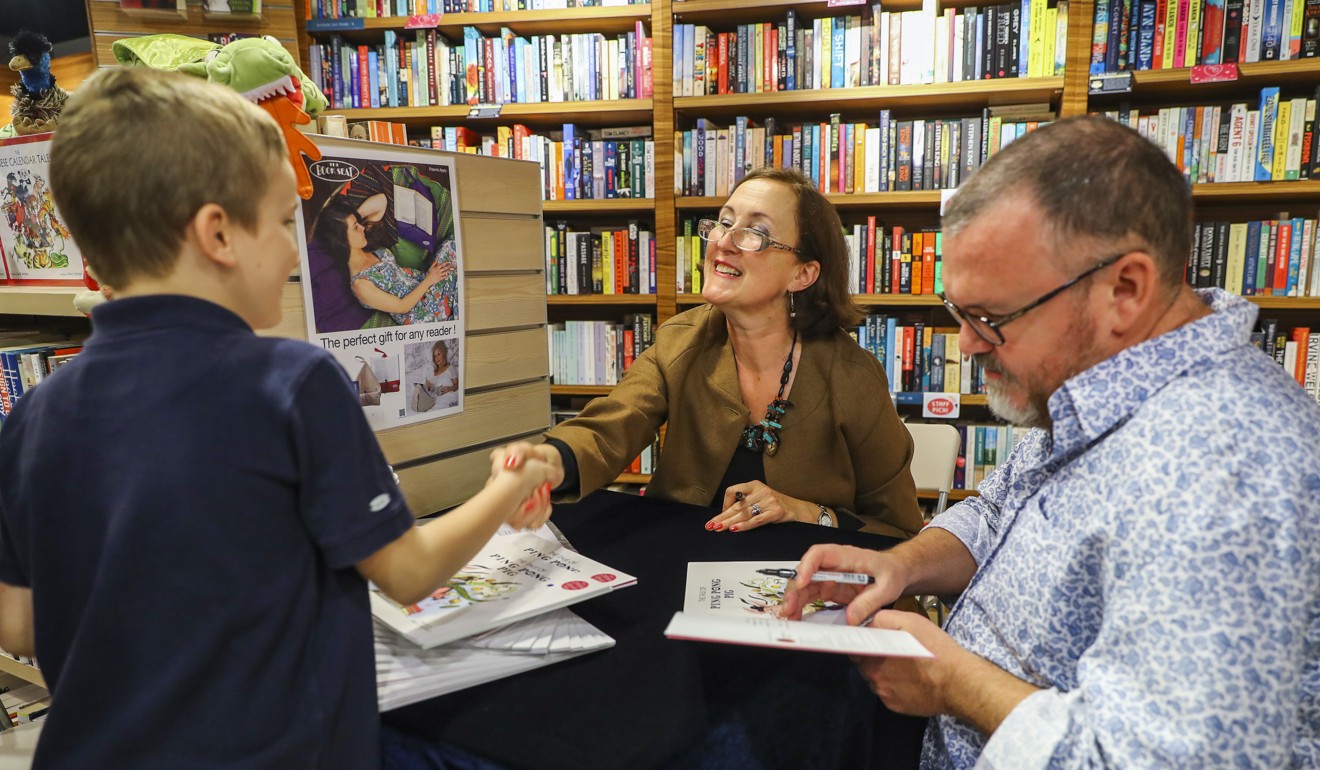

Four days afterwards, on, as it happens, Australia Day, The Tale of Ping Pong Pig is launched at Bookazine in Exchange Square. All the books are on display, either singly (HK$97) or in boxed sets (HK$1,199); 20 per cent of the day’s sales are being donated to Room To Read. Now that the series is complete, it’s easier to admire the amazing achievement – the extraordinary evolution from a boy-snacking dragon to a sophisticated pig that entrances the Yongle Emperor.

Another dozen children perch on tiny seats while Brennan vigorously re-enacts Ping Pong’s adventures. Afterwards, she and Harrison conduct a Calendar Tales mini-quiz. Brennan wants to know which Calendar Tales beat Harry Potter in Hong Kong’s bestseller lists.

Harrison, being a low-key wag who’d probably rather be at home on Lamma, gazes into those little eager faces and solemnly asks, “Does the co-location facility at West Kowloon railway station set a dangerous precedent?” It’s not exactly the Neats vs the Grots but they are very different people.

“She’s absolutely driven,” agrees Harrison (an Ox) afterwards. “That’s where we clash. It’s her focus, it’s not my focus. For me, it’s a job.

“We’ve had some terrible arguments. I never used to show her the illustrations but little by little that changed. The books became more fact-based and historically accurate. I’d be going, ‘Who gives a s***?”

Still, the pair managed to stick it out. (As he puts it, “The beauty of doing one book a year is that there’s a cooling-off period.”) Now that the series has ended, he says, “I’ll crack on with my own stuff again and see what happens.”

In 2017, Brennan’s lyrical children’s book Storm Whale, set in Tasmania, was published by Allen and Unwin in Australia. (The illustrations are by Jane Tanner.) It’s about the brief shadow of danger that suddenly clouds a childhood day – about trying to save something special. Last year it was shortlisted for several prestigious prizes, including Australia’s Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

I thought she might publish more of her own books now but she says not: “You always have to decide – am I a publisher or an author? I’m an author. But I just don’t have the time to write. That’s the downside of publishing. I’ve written a book a year and put it out and marketed the hell out of it.” For just a second, she seems conflicted. Then Single-minded Sarah re-emerges.

Her next great challenge, she says, is the internet and maximising sales online.