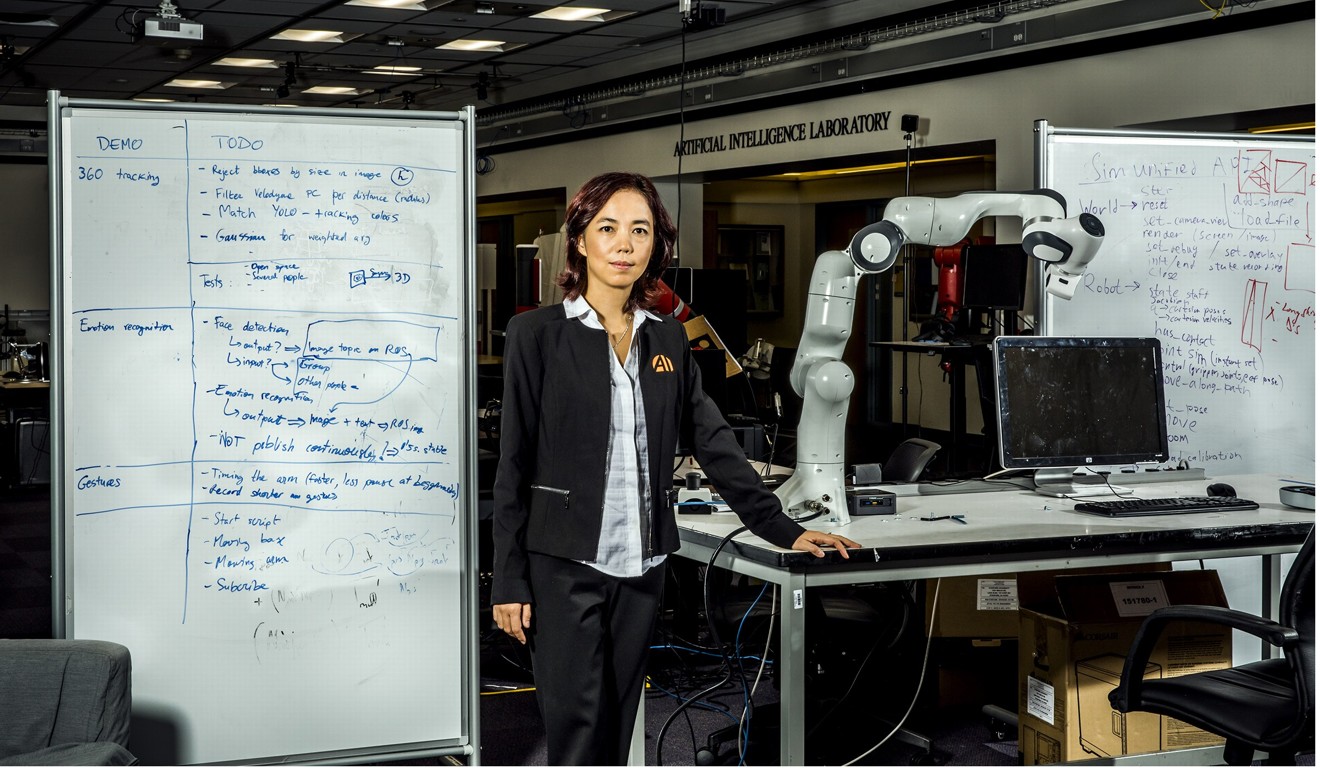

Bias in, bias out: the Stanford scientist out to make AI less white and male

- Chinese-American Fei-Fei Li, an expert in deep learning who helped rewrite Google’s ethics rules, wants more women and minorities in artificial intelligence

- She says how AI is engineered, and by whom, will determine whether it helps all humanity or reinforces the wealth divide and human prejudices

Sometime around 1am on a warm night in June 2017, Fei-Fei Li was sitting in her pyjamas in a Washington, DC hotel room, practising a speech she would give in a few hours. Before going to bed, Li cut a full paragraph from her notes to be sure she could reach her most important points in the short time allotted. When she woke up, the five-foot three-inch expert in artificial intelligence put on boots and a black and navy knit dress, a departure from her frequent uniform of a T-shirt and jeans. Then she took an Uber to the Rayburn House Office Building, just south of the United States Capitol.

Before entering the chambers of the US House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology, she lifted her phone to snap a photo of the oversized wooden doors. (“As a scientist, I feel special about the committee,” she says.) Then she stepped inside the cavernous room and walked to the witness table.

It’s 2030 and AI has changed so much – for better or worse?

The hearing that morning, titled “Artificial Intelligence – With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility,” included Timothy Persons, chief scientist of the Government Accountability Office, and Greg Brockman, co-founder and chief technology officer of the non-profit organisation OpenAI. But only Li, the sole woman at the table, could lay claim to a groundbreaking accomplishment in the field of AI. As the researcher who built ImageNet, a database that helps computers recognise images, she’s one of a tiny group of scientists – a group perhaps small enough to fit around a kitchen table – who are responsible for AI’s recent remarkable advances.

That June, Li was serving as the chief artificial intelligence scientist at Google Cloud and was on leave from her position as director of the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Lab. But she was appearing in front of the committee because she was also the co-founder of a non-profit focused on recruiting women and people of colour to become builders of artificial intelligence.

It was no surprise that the legislators sought her expertise that day. What was surprising was the content of her talk: the grave dangers inherent in the field she so loved.

The time between an invention and its impact can be short. With the help of artificial intelligence tools like ImageNet, a computer can be taught to learn a specific task and then act far faster than a person ever could. As this technology becomes more sophisticated, it’s being deputised to filter, sort and analyse data and make decisions of global and social consequence.

Though these tools have been around, in one way or another, for more than 60 years, in the past decade we’ve started using them for tasks that change the trajectory of human lives: today, AI helps determine which treatments get used on people with illnesses, who qualifies for life insurance, how much prison time a person serves, which job applicants get interviews.

There’s nothing artificial about AI. It’s inspired by people, it’s created by people, and – most importantly – it impacts people. It is a powerful tool we are only just beginning to understand, and that is a profound responsibility

Li was testifying in the Rayburn building that morning because she is adamant her field needs a recalibration. Prominent, powerful and mostly male tech leaders have been warning about a future in which AI-driven technology becomes an existential threat to humans. But Li says those fears are given too much weight and attention. She is focused on a less melodramatic but more consequential question: how AI will affect the way people work and live. It’s bound to alter the human experience – and not necessarily for the better.

“We have time,” Li said, “but we have to act now.” If we make fundamental changes to how AI is engineered – and who engineers it – the technology, Li argues, will be a transformative force for good. If not, we are leaving a lot of humanity out of the equation.

At the hearing, Li was the last to speak. With no evidence of the nerves that had driven her late-night preparation, she began. “There’s nothing artificial about AI.” Her voice picked up momentum. “It’s inspired by people, it’s created by people, and – most importantly – it impacts people. It is a powerful tool we are only just beginning to understand, and that is a profound responsibility.” Around her, faces brightened. The woman who kept attendance agreed audibly, with an “mm-hmm”.

Fei-Fei Li grew up in Chengdu, Sichuan province. She was a lonely, brainy kid and an avid reader. Her family was a bit unusual: in a culture that didn’t prize pets, her father brought her a puppy. Her mother, who had come from an intellectual background, encouraged her to read Jane Eyre. (“Emily is my favourite Brontë,” Li says. “Wuthering Heights.”)

When Fei-Fei was 12, her father emigrated to Parsippany, New Jersey, and she and her mother didn’t see him for several years. They joined him when she was 16. On her second day in America, Fei-Fei’s father took her to a service station and asked her to tell the mechanic to fix his car. She spoke little English, but through gestures the girl figured out how to explain the problem. Within two years, Li had learned enough of the language to serve as a translator, interpreter and advocate for her mother and father, who had learned only the most basic English. “I had to become the mouth and ears of my parents,” she says.

She was also doing well in school. Her father, who loved to scour garage sales, found her a scientific calculator, which she used in maths class until a teacher, sizing up her mistaken calculations, figured out that it had a broken function key.

Li credits another high school maths instructor, Bob Sabella, for helping her navigate her academic life and her new American identity. Parsippany High School didn’t have an advanced calculus class, so he concocted an ad hoc version and taught Li during lunch breaks. Sabella and his wife also included her in their family, taking her on a Disney holiday and lending her US$20,000 to open a dry-cleaning business for her parents to run. In 1995, she earned a scholarship to study at Princeton University. While there, she travelled home nearly every weekend to help run the family business.

Hong Kong’s best minds must work together to shape AI future

At college, Li’s interests were expansive. She majored in physics and studied computer science and engineering. In 2000, she began a doctorate at the California Institute of Technology, in Pasadena, working at the intersection of neuroscience and computer science.

Her ability to see and foster connections between seemingly dissimilar fields is what led Li to think up ImageNet. Her computer-vision peers were working on models to help computers perceive and decode images, but those models were limited in scope: a researcher might write one algorithm to identify dogs and another to identify cats.

Li began to wonder if the problem wasn’t the model but the data. She thought that, if a child learns to see by experiencing the visual world – by observing countless objects and scenes in her early years – maybe a computer could learn in a similar way, by analysing a wide variety of images and the relationships between them. “It was a way to organise the whole visual concept of the world,” she says.

But she had trouble convincing her colleagues that it was rational to undertake the gargantuan task of tagging every possible picture of every object in one gigantic database. What’s more, Li had decided that for the idea to work, the labels would need to range from the general (“mammal”) to the highly specific (“star-nosed mole”). When Li, who had moved back to Princeton to take a job as an assistant professor in 2007, talked up her idea for ImageNet, she had a hard time getting faculty members to help out. Finally, a professor who specialised in computer architecture agreed to join her as a collaborator.

AI revolution needs old-fashioned manual labour – from China

Her next challenge was to get the giant thing built. That meant a lot of people would have to spend a lot of hours doing the tedious work of tagging photos. Li tried paying Princeton students US$10 an hour, but progress was slow. Then a student asked her if she’d heard of Amazon Mechanical Turk. Suddenly she could corral many workers, at a fraction of the cost. But expanding a workforce from a handful of Princeton students to tens of thousands of invisible Turkers had its own challenges.

Li had to factor in the workers’ likely biases. “Online workers, their goal is to make money the easiest way, right?” she says. “If you ask them to select panda bears from 100 images, what stops them from just clicking everything?” So she embedded and tracked certain images – such as pictures of golden retrievers that had already been correctly identified as dogs – to serve as a control group. If the Turks labelled these images properly, they were working honestly.

In 2009, Li’s team felt the massive set – 3.2 million images – was comprehensive enough to use, and they published a paper on it, along with the database. (It grew to 15 million.) At first the project got little attention. But then the team had an idea: they reached out to the organisers of a computer-vision competition taking place the following year in Europe and asked them to allow competitors to use the ImageNet database to train their algorithms. This became the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge.

At about the same time, Li joined Stanford University as an assistant professor. She was, by then, married to Silvio Savarese, a roboticist. But he had a job at the University of Michigan, and the distance was tough. “We knew Silicon Valley would be easier for us to solve our two-body problem,” Li says. (Savarese joined Stanford’s faculty in 2013.) “Also, Stanford is special because it’s one of the birthplaces of AI.”

In 2012, University of Toronto researcher Geoffrey Hinton entered the ImageNet competition, using the database to train a type of AI known as a deep neural network. It turned out to be far more accurate than anything that had come before – and he won. Li was on maternity leave, and the award ceremony was happening in Florence, Italy. But she recognised that history was being made. So she bought a last-minute ticket and crammed herself into a middle seat for an overnight flight.

Hinton’s ImageNet-powered neural network changed everything. By 2017, the final year of the competition, the error rate for computers identifying objects in images had been reduced to less than 3 per cent, from 15 per cent in 2012. Computers, at least by one measure, had become better at seeing than humans.

ImageNet enabled deep learning to go big – it’s at the root of recent advances in self-driving cars, facial recognition, phone cameras that can identify objects (and tell you if they’re for sale).

Not long after Hinton accepted his prize, while Li was still on maternity leave, she started to think a lot about how few of her peers were women. She saw how the disparity was increasingly going to be a problem.

If we wake up 20 years from now and we see the lack of diversity in our tech and leaders and practitioners, that would be my doomsday scenario

Most scientists building AI algorithms were men, and often men of a similar background. They had a particular world view that bled into the projects they pursued and even the dangers they envisioned. Many of AI’s creators had been boys with sci-fi dreams, thinking up scenarios from The Terminator and Blade Runner. There’s nothing wrong with worrying about such things, Li thought, but those ideas betrayed a narrow view of the possible dangers of AI.

Deep learning systems are, as Li says, “bias in, bias out”. Li recognised that while the algorithms that drive AI may appear to be neutral, the data and applications that shape the outcomes of those algorithms are not. What mattered were the people building it and why they were building it.

Without a diverse group of engineers, Li pointed out that day on Capitol Hill, we could have biased algorithms making unfair loan-application decisions or training a neural network only on white faces – creating a model that would perform poorly on black or Asian ones. “I think if we wake up 20 years from now and we see the lack of diversity in our tech and leaders and practitioners, that would be my doomsday scenario,” she said.

It was critical, Li came to believe, to focus the development of AI on helping the human experience. One of her projects at Stanford was a partnership with the medical school to bring AI to the intensive-care unit (ICU) in an effort to cut down on problems such as hospital-acquired infections. It involved developing a camera system that could monitor a hand-washing station and alert hospital workers if they forgot to scrub properly. This type of interdisciplinary collaboration was unusual.

“No one else from computer science reached out to me,” says Arnold Milstein, a professor of medicine who directs Stanford’s Clinical Excellence Research Center.

That work gave Li hope for how AI could evolve. It could be built to complement people’s skills rather than simply replace them. If engineers engaged with people in other disciplines – even people in the real world – they could make tools that expand human capacity, like automating time-consuming tasks to allow ICU nurses to spend more time with patients, rather than building AI, say, to automate the shopping experience and eliminate a cashier’s job.

Considering that AI was developing at warp speed, Li realised her team needed to change the roster – as fast as possible.

Li has always been drawn to maths, so she recognises that getting women and people of colour into computer science requires a colossal effort. According to the National Science Foundation, in 2000, women earned 28 per cent of bachelor’s degrees in computer science. In 2015, that figure was 18 per cent. Even in her own lab, Li struggles to recruit people of colour and women.

Though historically more diverse than your typical AI lab, it remains predominantly male, she says. “We still do not have enough women, and especially under-represented minorities, even in the pipeline coming into the lab,” she says. “Students go to an AI conference and they see 90 per cent people of the same gender. And they don’t see African Americans nearly as much as white boys.”

A who’s who of women leaders in China’s tech industry

Olga Russakovsky had almost written off the field when Li became her adviser. Russakovsky was already an accomplished computer scientist – with an undergraduate degree in maths and a master’s in computer science, both from Stanford – but her dissertation work was dragging. She felt disconnected from her peers as the only woman in her lab. Things changed when Li arrived at Stanford.

Li helped Russakovsky learn skills required for successful research, “but also she helped build up my self-confidence”, says Russakovsky, who is now an assistant professor in computer science at Princeton.

Four years ago, as Russakovsky was finishing her PhD, she asked Li to help her create a summer camp to get girls interested in AI. They pulled volunteers together and posted a call for high school sophomores. Within a month, they had 200 applications for 24 spots. Two years later they expanded the programme, launching the non-profit AI4All to bring under-represented youth – including people of colour and those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds – to the campuses of Stanford and the University of California, Berkeley.

AI4All is on the verge of growing out of its tiny shared office at the Kapor Center, in downtown Oakland, California. It now has camps at six college campuses. (Last year there were 900 applications for 20 spots at the newly launched Carnegie Mellon camp.) One AI4All student worked on detecting eye diseases using computer vision. Another used AI to write a program ranking the urgency of calls to the emergency services; her grandmother had died because an ambulance didn’t reach her in time. Confirmation, it would seem, that personal perspective makes a difference for the future of AI tools.

After three years running the AI Lab at Stanford, Li took a sabbatical in 2016 to join Google as chief scientist for AI of Google Cloud, the company’s enterprise computing business. Li wanted to understand how industry worked and to see if access to customers anxious to deploy new tools would shift the scope of her own cross-disciplinary research.

Companies such as Facebook, Google and Microsoft were throwing money into AI in search of ways to harness the technology for their businesses. And companies often have more and better data than universities. For an AI researcher, data is fuel.

Initially the experience was enlivening. She met with companies that had real-world uses for her science. She led the roll-out of public-facing AI tools that let anyone create machine learning algorithms without writing a single line of code. She opened a lab in China and helped to shape AI tools to improve health care. She spoke at the World Economic Forum, in Davos, rubbing elbows with heads of state and pop stars.

It’s about the moment – the collective sense of urgency for our responsibility, the emerging power of AI, the dialogue that Silicon Valley needs to be in

Though Li hadn’t been involved directly with the deal, the division that she worked for was charged with administering Maven. And she became a public face of the controversy when emails she wrote that looked as if they were trying to help the company avoid embarrassment were leaked to The New York Times. Publicly this seemed confusing, as she was well known in the field as someone who embodied ethics. In truth, before the public outcry she had considered the technology to be “fairly innocuous”; she hadn’t considered that it could cause an employee revolt.

“It wasn’t exactly what the thing is. It’s about the moment – the collective sense of urgency for our responsibility, the emerging power of AI, the dialogue that Silicon Valley needs to be in. Maven just became kind of a convergence point,” she says. The Google motto “Don’t be evil” was no longer a strong enough stance.

The controversy subsided when Google announced it wouldn’t renew the Maven contract. A group of Google scientists and executives – including Li – also wrote (public) guidelines pledging that Google would focus its AI research on technology designed for social good, would avoid implementing bias into its tools and would avoid technology that could end up facilitating harm to people. Li had been preparing to head back to Stanford but she felt it was critical to see the guidelines through.

“I think it’s important to recognise that every organisation has to have a set of principles and responsible review processes. You know how Benjamin Franklin said, when the Constitution was rolled out, it might not be perfect but it’s the best we’ve got for now,” she says. “People will still have opinions, and different sides can continue the dialogue.” But when the guidelines were published, she says, it was one of her happiest days: “It was so important for me personally to be involved, to contribute.”

There are no independent machine values. Machine values are human values

In June last year, I visited Li at her home, a modest split-level in a cul-de-sac on the Stanford campus. It was just after 8pm and while we talked her husband put their young son and daughter through their bedtime routines upstairs. Her parents were home for the night in the in-law unit downstairs. The dining room had been turned into a playroom, so we sat in her living room. Family photos rested on every surface, and a broken 1930s-era telephone sat on a shelf. “Immigrant parents!” she said when I asked her about it. Her father still likes to go to garage sales.

As we talked, text messages started pinging on Li’s phone. Her parents were asking her to translate a doctor’s instructions for her mother’s medication. Li can be in a meeting at the Googleplex or speaking at the World Economic Forum or sitting in the green room before a congressional hearing and her parents will text her for a quick assist. She responds without breaking her train of thought.

For much of Li’s life, she has been focused on two seemingly different things at the same time. She is a scientist who has thought deeply about art. She is an American who is Chinese. She is as obsessed with robots as she is with humans.

Late in July, Li called me while she was packing for a family trip and helping her daughter wash her hands. “Did you see the announcement of Shannon Vallor?” she asked. Vallor’s research focuses on the philosophy and ethics of emerging science and technologies, and she had just signed on to work for Google Cloud as a consulting ethicist. Li had campaigned hard for this; she’d even quoted Vallor in her testimony in Washington, saying: “There are no independent machine values. Machine values are human values.”

The appointment wasn’t without precedent. Other companies have also started to put guardrails on how their AI software can be used, and who can use it. Microsoft established an internal ethics board in 2016. The company says it has turned down business with potential customers owing to ethical concerns brought forward by the board. It’s also begun placing limits on how its AI tech can be used, such as forbidding some applications in facial recognition.

But to speak on behalf of ethics from inside a corporation is, to some extent, to acknowledge that, while you can guard the henhouse, you are indeed a fox. When we talked in July, Li already knew she was leaving Google. Her two-year sabbatical was coming to an end. The reason for her return to Stanford, she said, was that she didn’t want to forfeit her academic position. She also sounded tired. After a tumultuous summer at Google, the ethics guidelines she helped write were “the light at the end of the tunnel”.

Last autumn, she and John Etchemendy, the former Stanford provost, announced the creation of an academic centre that will fuse the study of AI and humanity, blending hard science, design research and interdisciplinary studies. “As a new science, AI never had a field-wide effort to engage humanists and social scientists,” she says. Those skill sets have long been viewed as inconsequential to the field of AI, but Li is adamant that they are key to its future.

Li is fundamentally optimistic. At the hearing last June, she told the legislators, “I think deeply about the jobs that are currently dangerous and harmful for humans, from fighting fires to search and rescue to natural disaster recovery.” She believes that we should not only avoid putting people in harm’s way when possible, but that these are often the very jobs where technology can be a great help.

With proper guidance AI will make life better. But without it, the technology stands to widen the wealth divide even further, make tech even more exclusive and reinforce biases we’ve spent generations trying to overcome

There are limits, of course, to how much a single programme at a single institution – even a prominent one – can shift an entire field. But Li is adamant she has to do what she can to train researchers to think like ethicists, who are guided by principle over profit, informed by a varied array of backgrounds.

On the phone, I ask Li if she imagines there could have been a way to develop AI differently, without, perhaps, the problems we’ve seen so far. “I think it’s hard to imagine,” she says. “Scientific advances and innovation come really through generations of tedious work, trial and error. It took a while for us to recognise such bias. I only woke up six years ago and realised, ‘Oh my God, we’re entering a crisis.’”

On Capitol Hill, Li said, “As a scientist, I’m humbled by how nascent the science of AI is. It is the science of only 60 years. Compared with classic sciences that are making human life better every day – physics, chemistry, biology – there’s a long, long way to go for AI to realise its potential to help people.” She added, “With proper guidance AI will make life better. But without it, the technology stands to widen the wealth divide even further, make tech even more exclusive and reinforce biases we’ve spent generations trying to overcome.”

This is the time, Li would have us believe, between an invention and its impact.