On the trail of Deng Xiaoping in the French town where he embraced Communism

- In the 1920s, the man who would become China’s paramount leader found his raison d’être in unremarkable Montargis, 120km from Paris

- Students sent to France to learn from the West made the town a hotbed of Chinese Communist thought

Baoding is a sizeable city in central Hebei province, in north China, and synonymous with heavy industry and its attendant ills. Its hardy people – mostly of the country’s Han majority – wear no-nonsense expressions and display a hardheadedness born of stoicism. A showcase city Baoding is not.

Yet neither is it poor. As I walk the streets, the trappings of 21st-century capitalism protrude between the Mao-era tenements and identikit high-rise apartment blocks. There are fast-food joints, a few garish shopping malls and a railway station so big it makes those in Europe look like toy models.

Where to now? 40 years after the big experiment that changed China

Not far from the station, on Yuhua West Road, stands a large, unremarkable middle school that could exist anywhere in China. At the back of the school, on Jingtaiyi Road, a few Taoist fortune-tellers line the route to the gate of a small building fashioned in the Ming style. A sign above the door bears the calligraphic script of former Chinese president Jiang Zemin. It reads, Liu Fa Qingong Xianxue Yundong Jinnianguan, or, “The Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement Museum”.

The museum tells of aspirational young Chinese who went to France and Belgium to work and study a century ago, lured by the promise of acquiring the modern skills and technology with which they might help develop their motherland. The well-intentioned initiative lasted from 1908 to 1927, but ultimately failed due to the miserable conditions many of the Chinese endured, exploited at the hands of factory owners or deprived of the schooling they had been promised.

Despite the movement’s failings, and due to its celebrity alumnus (namely Deng Xiaoping, who would go on to become China’s paramount leader), the Mouvement Travail-Études has become central to Chinese Communist Party mythology, much like the Long March. Yet despite the propaganda element (posters recalling China’s century of humiliation at the hands of foreign imperialists, for instance), the museum’s curators have brought to light an often-skimmed-over chapter in modern Chinese history.

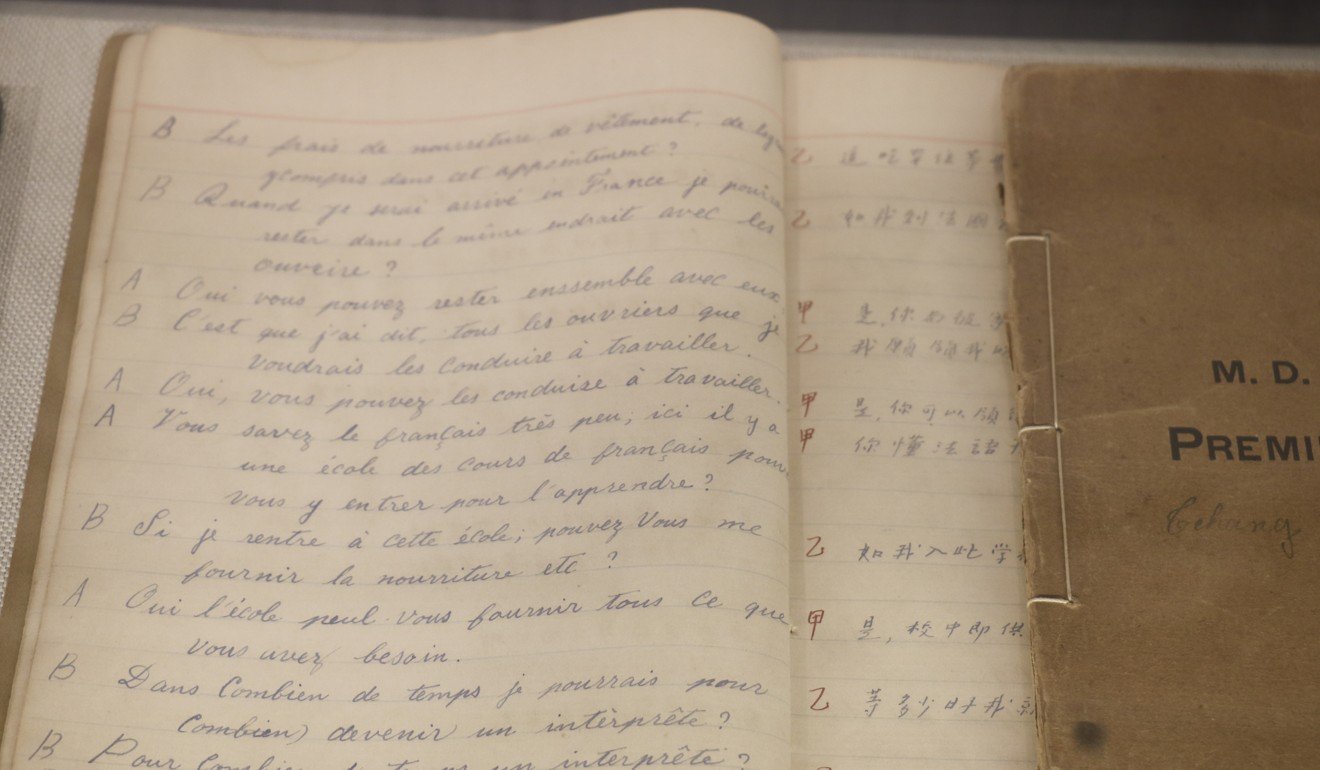

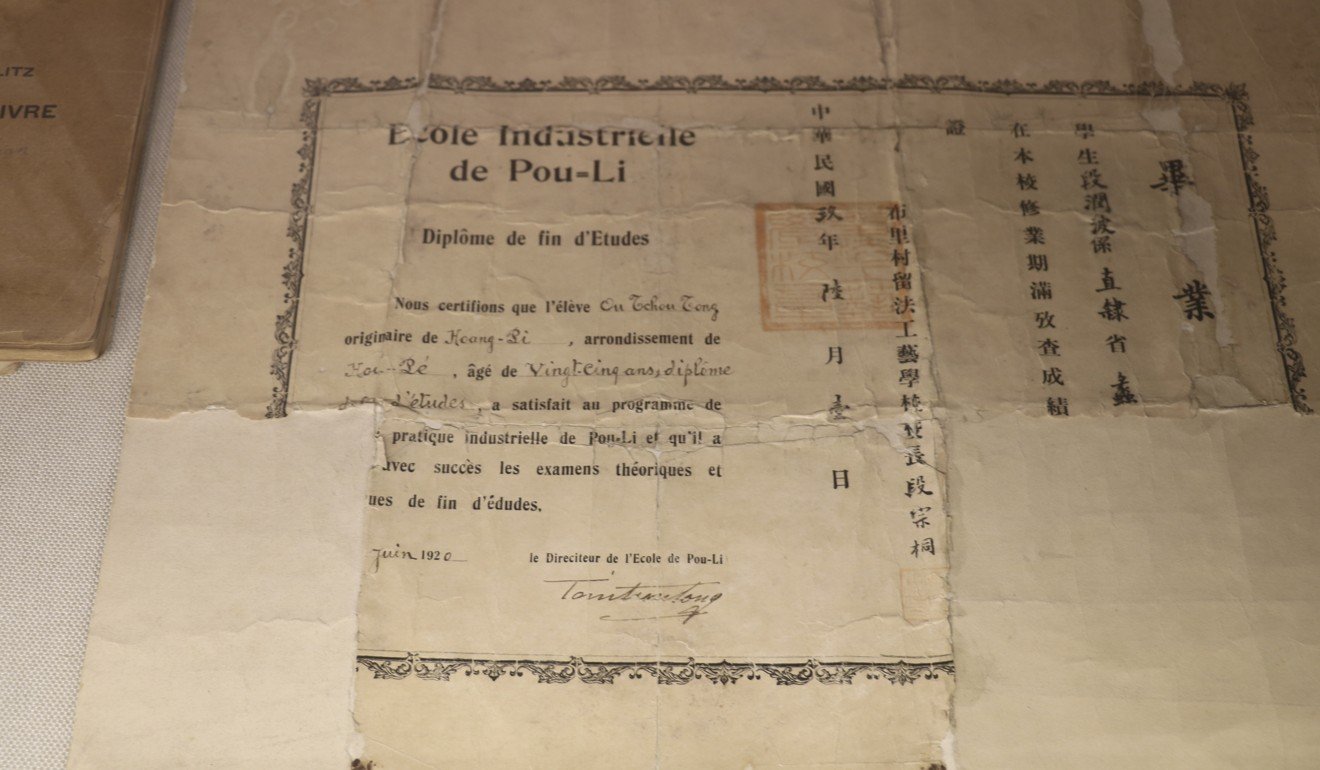

Heart-rending poems penned by homesick students adorn the walls; black-and-white photos show the youngsters in exotic French locales; and cases display exercise books containing handwritten French homework and moth-eaten diplomas from French universities.

Deng hailed from Sichuan province, specifically from Paifang, which today is close to the border with Chongqing municipality. While the Chinese Communist Party is a zealous (some might say overzealous) custodian of its own history, Deng did not go to school 1,600km north of his hometown. So why is this backstreet museum in Baoding?

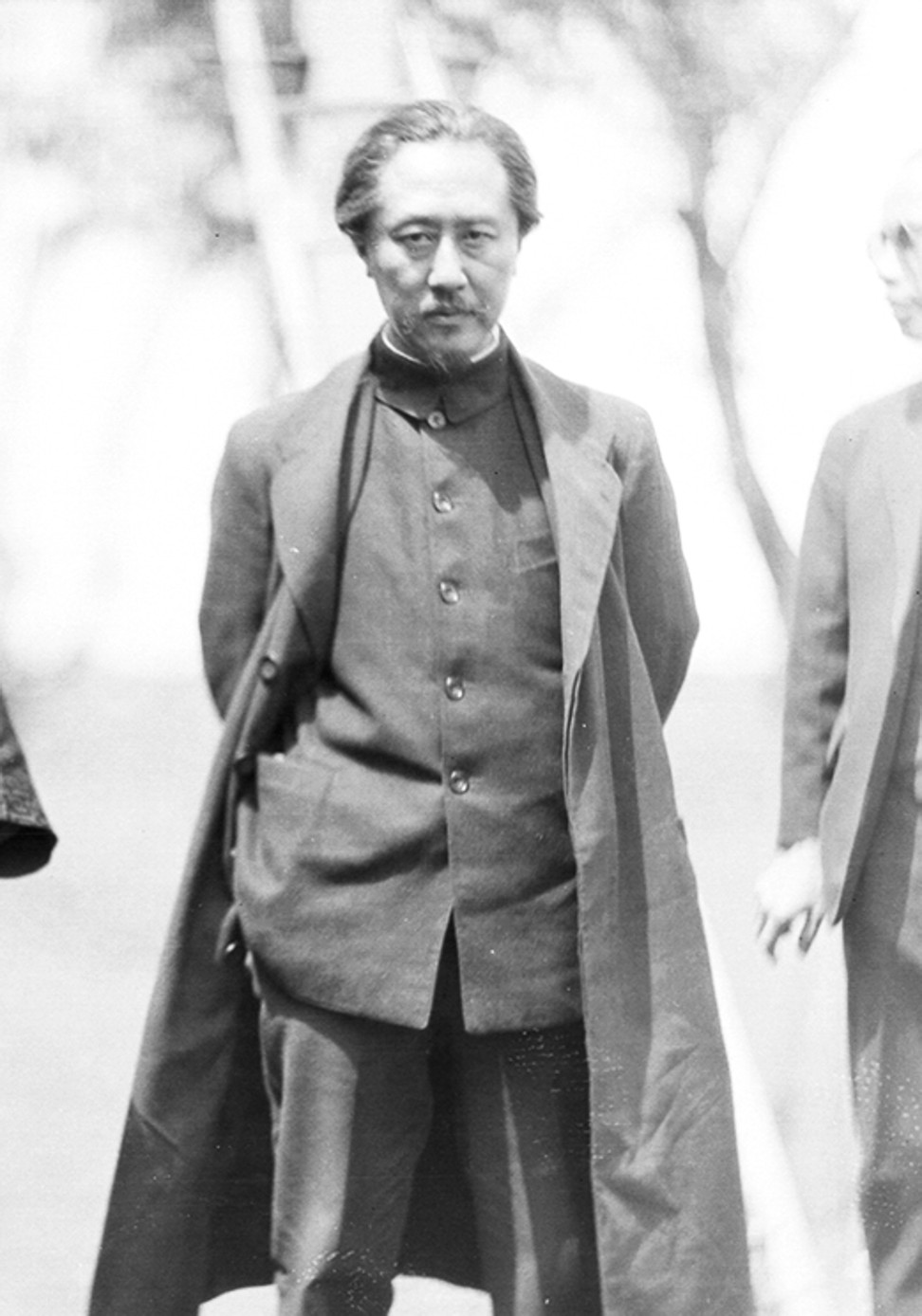

Another plaque, this time inside the museum, explains that it occupies the grounds of the Yude Middle School, which was one of the first schools to participate in the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement, which had been dreamed up by Li Shizeng, whose family hailed from this part of Hebei.

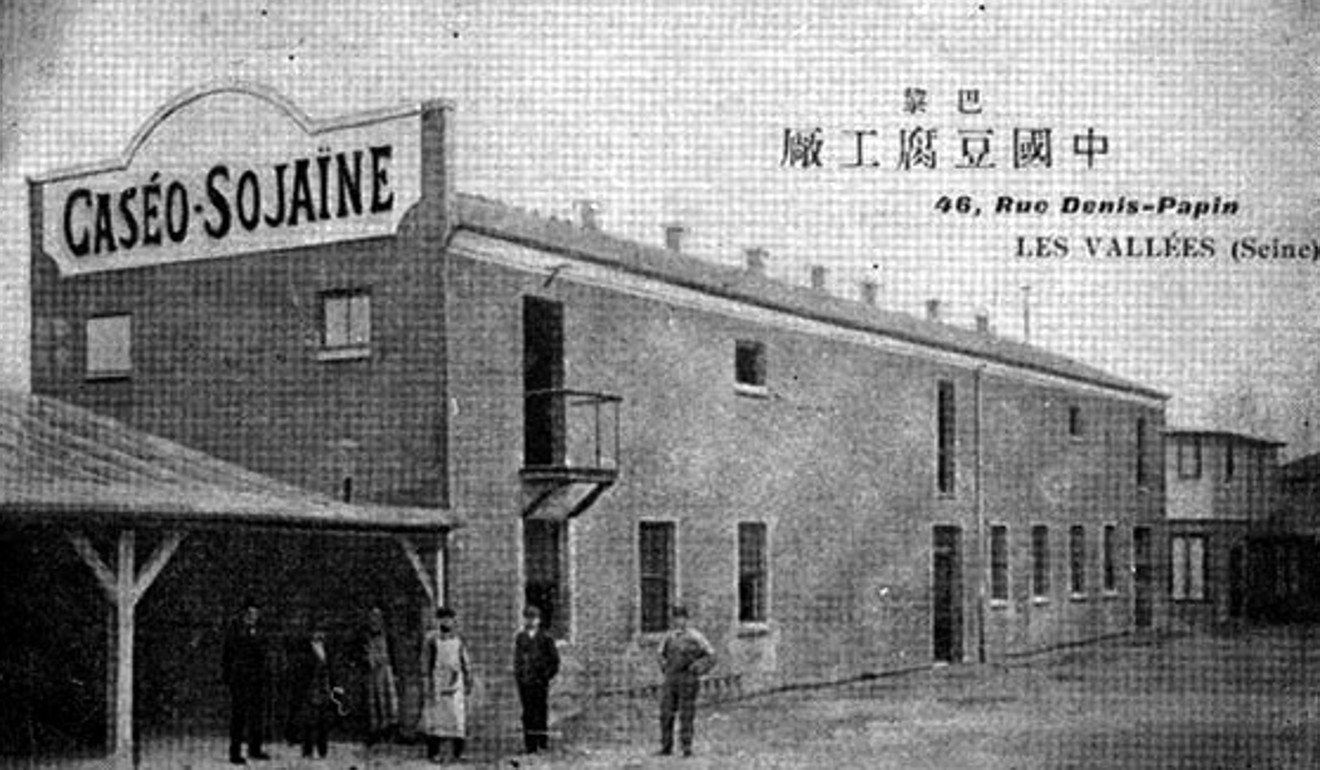

Born into privilege in 1881, in the ailing years of the Qing dynasty, Li journeyed to France in 1902, where he studied science and supported revolutionary Sun Yat-sen through political activism. In 1908, entrepreneurial Li opened Europe’s first bean curd factory, Usine de la Caséo-Sojaïne, in a Paris suburb. He used the factory as a base for his Sino-Franco exchange programme – a project that would dominate the next 20 years of his life.

Though he enjoyed a politically active and long life (he died aged 92, in Taiwan), Li’s devotion to the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang, which fought against the Communist Party for control of China in the country’s civil war, explains why his story is only half told in the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement Museum, his star largely eclipsed by that of Deng.

The scale of the Sino-French connection that Li (and other well-meaning expatriates) established is illustrated by a map of France on display in the museum. It pinpoints the many locations that young Chinese men and women found themselves in, from remote villages to central Paris.

Between 1919 and 1921 alone, some 1,600 arrived in the country to partake in the scheme, and a photograph in the museum shows the unveiling of a commemorative signpost in France in 2014, marking a square to be named Place Deng Xiaoping, an honour usually reserved for home-grown heroes such as Charles de Gaulle and Léon Gambetta.

Liu Yandong, then a vice-premier of China, was at the ceremony. The location, written in Chinese characters, is Meng Da Er. I check my phone’s Chinese dictionary app: the square is in a place called Montargis.

Starting out in Shanghai, Chinese students heading for France in the 1920s first sailed via Hong Kong to Saigon, and then through the Strait of Malacca and on to Ceylon. They navigated the Red Sea and the Suez Canal before docking in one of the port cities along France’s Mediterranean coast.

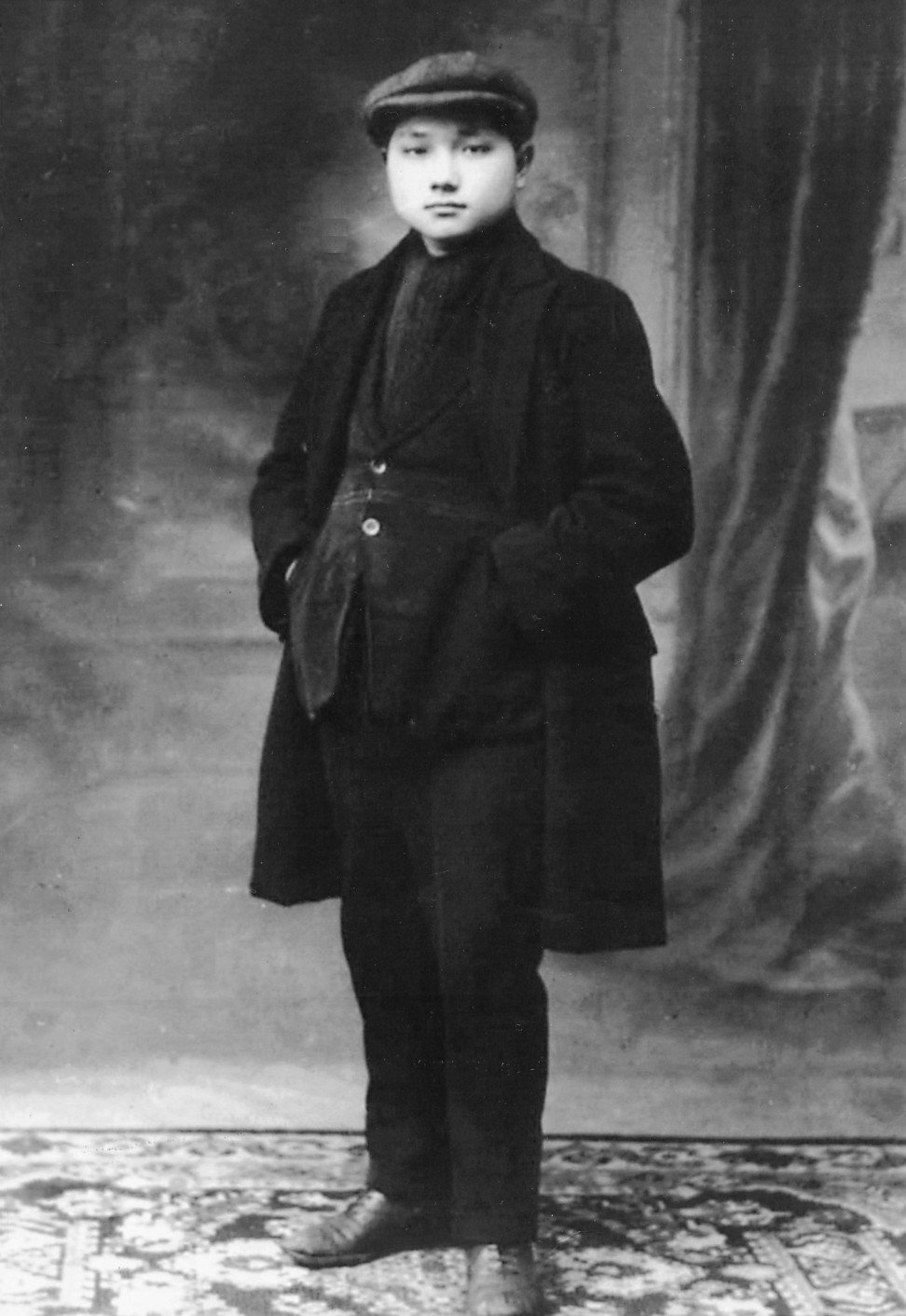

Deng and a group of students from Sichuan were among them. After a year of preparatory schooling in Chongqing, the 16-year-old had boarded a steamer at the Yangtze River port of Wanxian on August 27, 1920. Once in Shanghai, he boarded a French liner bound for Marseilles. The sea voyage took 39 days.

Yet while this industrialised, developed country impressed the youngster, Deng soon fell on hard times.

French soldiers who had survived the first world war returned home to work, and jobs became scarce and inflation was severe. Three months after Deng arrived, the Sichuan group broke off relations with the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement and his money dried up.

For the next three years, Deng lived on the margins of society, often without money for tuition or even food, experiences that ultimately shaped his political outlook. His first job was labouring in abysmal conditions in a steel mill in Le Creusot. Later, he worked at a factory in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, where for just a few weeks he made paper flowers. On February 14, 1922, Deng found his way to Montargis, an obscure town about 120km south of the capital, and then a hub for the Mouvement Travail-Études.

Paris has many beautiful railway stations. Built in the 1970s, Gare de Paris-Bercy-Bourgogne-Pays d’Auvergne is, alas, not one of them.

At 6.02pm, the Montargis train lurches into motion and we are soon rolling away from the suburbs and into the forested countryside of north-central France. Compared with contemporary China’s dilapidated rural villages and endless construction sites, there is a timeless elegance to the scene passing the window.

Exiting Montargis station little more than an hour later, I spot the signpost highlighted in Baoding, written in French and Chinese, and declaring a small station car park to be, as of 2014, Place Deng Xiaoping.

There is a photograph of the young Deng, wearing a suit and flat cap, his hands in his pockets. The accompanying text reads, “À la mémoire de Deng Xiaoping, ancien grand dirigeant de la République populaire de Chine, venu étudier et travailler dans Montargois dans les années 1920,” or, “In memory of Deng Xiaoping, former great leader of the People’s Republic of China, who studied and worked in Montargis in the 1920s.”

That evening, after consuming a bottle of Saint-Émilion wine, all I manage to write in my diary is, “I’ve found the man!”

Morning reveals Montargis to be, superficially at least, a typically quaint French provincial town. Centred on the Church of Sainte-Madeleine, with its spectacular stained-glass windows, the medieval old quarter has been meticulously preserved. The local cuisine is exquisite (though service standards vary). Several canals snake through the town (imbuing it with excellent feng shui, perhaps) and are crossed by a variety of bridges, some being hundreds of years old and arching like classical Chinese moon bridges. These must have seemed familiar to the Chinese who came to call Montargis home.

There is not much going on in Montargis when I visit. Half the townspeople appear to have shut up shop and migrated south for the summer; those who remain have organised a lacklustre agricultural festival. Saffron, honey and nutty pralines are the region’s notable produce, I learn.

The local tourist office has made it easy to explore sites associated with what it calls “l’amité Franco-Chinoise”, providing me with an illustrated town map highlighting all the places linked to the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement.

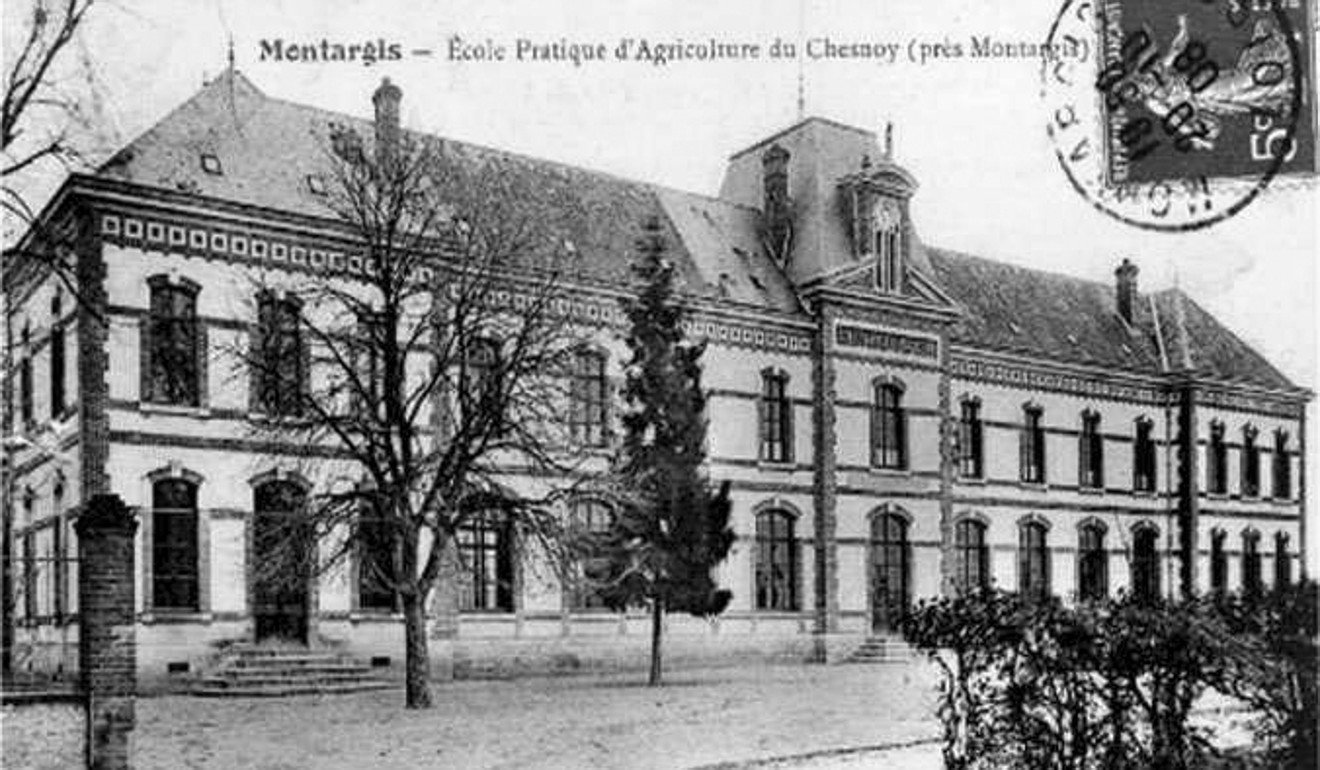

In the centre of town, 31 rue Gambetta became Li Shizeng’s address after he stumbled on Montargis in 1904 and was taken by its easy-going charm. He enrolled in the nearby École Pratique d’Agriculture du Chesnoy, the agricultural school where he studied for two years before developing his soybean business.

Li continued to base himself in Montargis, with its rail connection to the capital (the journey took four hours back then). The house he lived in now bears a blue panel acknowledging him as a “fils d’un conseiller de l’empereur de Chine” (“son of an adviser to the emperor of China”), and noting that he hosted Sun Yat-sen at the address.

It takes a day of walking to seek out and photograph all the notable sites on the list, including the former L’hôtel Durzy, where mayor Thierry Falour first met Li, in 1912, to discuss the idea of encouraging Chinese students to come and study in Montargis; the College Gambetta, where the many Chinese students included future foreign minister Chen Yi; and 15 rue Raymond Tellier, where several Chinese students rented rooms, among them Li Weihan, who, in 1982 and after a storied political career, became a deputy chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference.

The house on rue Raymond Tellier is now a museum that, like its Baoding counterpart, emphasises how many high-ranking Communist Party officials cemented their ideological ideas in Montargis, or cut their revolutionary teeth in France. “Be careful, there’s a lot of propaganda,” says the young man behind the museum’s front desk, with a chuckle. We speak first in French, then in Chinese and then English. Justin Chung, a part-time employee of the museum who hails from Changde, in northern Hunan province, is undertaking a PhD in Paris.

Of the Chinese who came to Montargis, Chung says, “Most were Hunanese. Li Weihan was from Hunan, and so was Cai Hesen, who was a close friend of Mao Zedong. That’s why the Hunan provincial government partly funded this museum.”

He adds that while some of those who came to Montargis as part of le mouvement did later take up positions of importance within the Chinese Communist Party, many others took no part in the revolutionary cause. The fact remains, however, that destiny brought Deng and company to this quiet commune on the Loing River, and here, almost 100 years ago, the seeds of a future China were sown.

In February 1922, Deng found work just north of Montargis, in Châlette-sur-Loing, at the Hutchinson rubber boot factory. He often worked 10 hours a day, saving enough money to enrol in a local college. When funds ran out, he was forced to return to the factory.

It was at this frustrating juncture in his life that Deng resolved to dedicate himself to politics, as Ezra F. Vogel notes in his book Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (2011): “After his last effort to find an opportunity to study failed, Deng devoted himself to the radical cause. While at Hutchinson the second time, he took part in study groups established by cells of secret Chinese Communist members in nearby Montargis, many of whom had been his classmates at the preparatory school in Chongqing.”

The failure of the Diligent Work-Frugal Study Movement to live up to expectations pushed the Chinese into closely knit communities across France. Among them circulated radical pamphlets and journals, including New Youth, a magazine published by influential revolutionary and philosopher Chen Duxiu, whose two sons were in France. For many, including Deng, the teachings of Karl Marx and other leftists resonated with their circumstances abroad, as well as with the woes afflicting their homeland.

In 1923, Deng left Montargis for Paris. There he worked for the Chinese Communist Party’s European wing under Zhou Enlai, who was also destined to become a key player in China’s evolution, and the first premier of the People’s Republic after 1949.

Every summer, Parisians flee the capital for the beaches of the Riviera, with Americans, other Europeans and the newcomers to the tourist jam – the Chinese – supplanting them. I watch a Chinese tour group being yelled at by a guide with a megaphone and a red flag. In a bistro, I observe a Chinese couple stare at some Camembert cheese with horror, perhaps wondering why, more than a century after Li’s tofu factory opened, the French are still fermenting cow’s milk.

Deng spent just over five years in France, four of them working. He never mastered French, as Zhou did. But he found his raison d’être in the country, and would remain a committed Communist Party man, for better or for worse, until his death, in 1997.

Deng’s career would see many ups and downs. During the 1950s and ’60s, he moved in the top echelons of power. Along with Liu Shaoqi, who was president of the People’s Republic from 1959 to 1968, he emphasised economics over ideological dogma, steering power away from Mao after the disastrous Great Leap Forward, which lasted from 1958 to 1962.

The Cultural Revolution saw Deng fall from grace, banished to work in a tractor factory in Jiangxi province. But after Mao’s death, in 1976, he gradually emerged as China’s de facto leader, outmanoeuvring political rivals such as Hua Guofeng and imprisoning enemies like the Gang of Four.

The great pragmatist put the economy back on track, founding Special Economic Zones such as Shenzhen, inviting foreign investment into the country and forging the unique brand of centrally planned market economics that has propelled China to the No 2 spot in the global economic charts.

To his adherents, Deng is remembered as a liberator of the impoverished. At an age when most people slumber into retirement, he became the first Chinese leader in history to visit Japan, was Time magazine’s “man of the year” twice, and negotiated with Britain the amicable return of Hong Kong. To his critics, he will forever be associated with the tanks rolling towards student protesters in Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Neither democracy nor the rule of law would take root under Deng’s tenure, nor in the climate he moulded for successors operating under the “socialism with Chinese characteristics” mandate.

Sauntering through Paris’ Latin Quarter – a hotbed of political activity between the wars – I wonder what elements of this complex character were forged in the furnaces of French mills, or here in a city brimming with ideas, where Deng first impressed his communist seniors when printing the group’s mimeographed journal, Red Light.

I stroll up rue Godefroy, where Zhou once lived. A marble plaque, using the old Wade-Giles spelling of his name, reads, “Chou En Laï (1898-1976) habita cet immeuble lors de son séjour en France de 1922 à 1924,” or, “Chou En Lai lived in this building during his stay in France from 1922 to 1924.”

As I round the corner onto Place d’Italie, I pass a branch of the Bank of China.