Coin stash that puts new spin on China’s 100 years of humiliation

Inside a nondescript Hong Kong warehouse sit seven tons of Qing dynasty coins – proof, their owner says, that it was the imperial monetary system, not the opium trade, that brought China low in the 19th century

Numismatics /ˌnjuːmɪzˈmatɪks/: The study or collection of coins, banknotes, and medals – Oxford English Dictionary

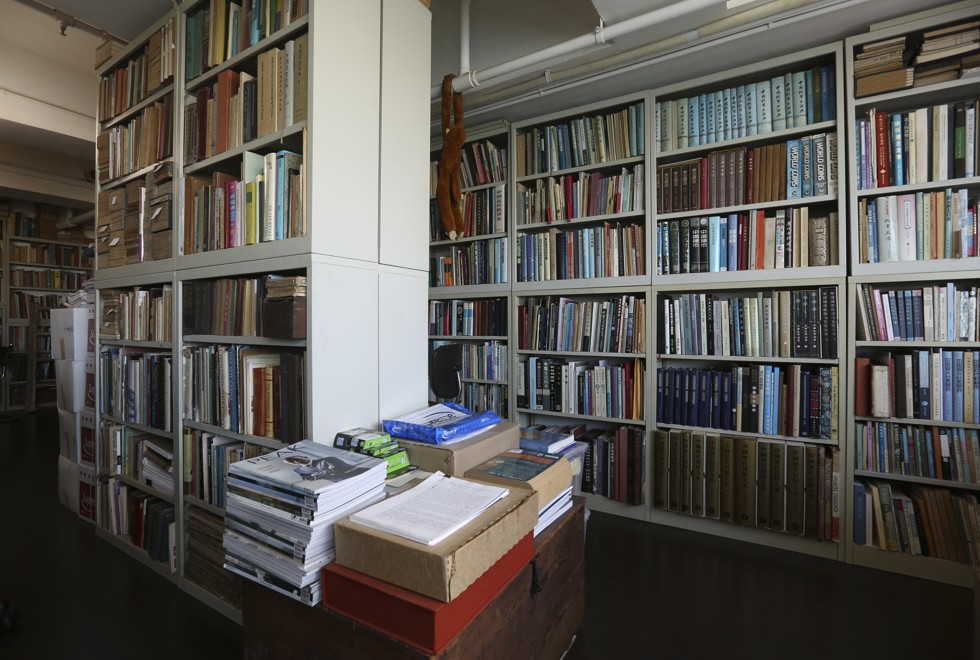

Sunlight barely reaches the depths of the cavernous, 5,000 sq ft warehouse space in Chai Wan where Dr Werner Burger and his Taiwanese-born wife, Tsai Yui-mei, who goes by the name Lucy, house seven tons of coins.

Dating from between 1636 and 1911, the span of China’s last imperial dynasty, the coins represent not only an extraordinary trove of rare and unique items coveted by collectors, but also a key to Hong Kong’s history.

Sitting in the midst of his treasure like a happy Bavarian elf is Burger, crippled by arthritis but enlivened by his passion, Qing dynasty coins, known as “cash”. At 81, the world’s pre-eminent collector of Qing cash can no longer walk, due to Charcot foot, a degenerative condition of the bones in his feet, but his mind is agile. Lucy, 10 years younger, hovers nearby, elegant, protective and observant as her husband spins a story she has doubtless heard many times.

The tale begins with a little boy in Bavaria stunned by his first encounter with Chinese culture through the beauty of classic Chinese painting. It drops by Shanghai under the Cultural Revolution, visits with a Hong Kong scrap dealer and his generous gift to a decidedly eccentric German friend, beats on the doors of China’s First Historical Archives, in Beijing, until they give way, and finally lingers many years in seclusion while Burger conducts research that a fellow academic, Fresco Sam-Sin, compares to “moving mountains”.

The devaluation of China’s currency through the course of the 19th century is a known cause of the weakness that led to dynastic collapse and the cession of Hong Kong to the British. However, before Burger, the mechanics behind the devaluation were unclear. The old cliché, that the British trade in opium depleted the Qing treasury of silver, leading to its downfall, is not true, Burger says. It was instead mismanagement of the monetary system, with roots long before the mid-19th century.

“I cannot stop wondering how every single 19th-century Chinese ruler ended up mismanaging the Chinese mints, making blunder after blunder,” he writes, in a landmark book on his collection that is itself epic in scale.

Other scholars have written about the impact of the Qing devaluations on social and economic disarray, but Burger is the first to display the entire sweep mint by mint, coin by coin. Sam-Sin, a Manchurian specialist at Leiden University, in the Netherlands, says simply, “The blood, sweat, tears [and his personal savings] that have gone into this publication are unprecedented.”

“Coins are the only antiques which we still have and can compare to the old records,” says Burger. “I can say, the official records are a bunch of lies.”

Born in 1936 in Munich, Germany, the year of the “Nazi Olympics” in Berlin, Burger was 13 when a teacher took him to a visiting exhibition of Chinese paintings. Frustrated that “nobody could read the bloody text”, he decided to study China.

“The more I knew, the more interesting it became, and the more excited I was,” he says. “I wanted to study Chinese and I wanted to marry a Chinese woman.”

Lucy demurs.

“You were 17, not 13,” she says. “But you realised both dreams.”

Having been one of eight young Germans studying Chinese at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (LMU), the country’s third-oldest university, when Burger graduated, in 1962 (the height of the cold war), his professors suggested he work on translations.

He wanted to study in China, and visited Bern, Switzerland, which then had the only Chinese embassy in Europe, to apply for a visa. The embassy asked if he could teach German and, six months later, he had a work visa for Beijing, which was changed to Shanghai after he had arrived in China via Czechoslovakia and Russia.

Shanghai was in the early stages of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, and increasingly hostile to foreigners as well as to scholarly endeavour. The Chinese teacher Burger hired was criticised for associating with a foreigner and the German was one of just three users of the Shanghai public library. Two years later, in 1965, the school in Shanghai where he taught was shut down and Burger was invited to become a sheep farmer in Suzhou.

What one can learn from how the Qing dynasty ran its show is that, although they were good book-keepers – much better than the British or the Germans – they did a lousy job of making a system of their economy.

“Sheep farming was not my cup of tea,” he says, so instead he bought a ticket to Hong Kong.

“And here I am still,” after 52 years, he says, with a sly smile. Hong Kong’s libraries and antiquarian resources were far superior to those in Shanghai, he says, but to study Qing numismatics, he had to range farther afield.

“I was very disappointed with Hong Kong universities at the time,” he says. “There was nothing at all on the last dynasty, although plenty on the earlier ones.”

While his erstwhile companions in the Shanghai public library were studying Marxism and waste water treatment, Burger became interested in Qing history, and gradually zeroed in on the study of money, or numismatics. The field began in China at least 1,000 years before it was established in Europe, with a lost 6th-century book, Qianzhi, the “record of money”, by Liu Qian (AD484-550).

Burger turned to LMU to pursue a doctorate, but when he asked his professors if he could study Chinese numismatics, they were baffled.

“I was the first and only PhD in Chinese numismatics,” he says. “My professors said, ‘Go talk to the economists.’ The economists said, ‘Go talk to the Sinologues.’”

Even today, it is a lonely field, with only one other specialist in the subject, Dr Lyce Jankowski, at Paris-Diderot University.

Burger began by looking at Qing records, but quickly found he needed to compare them with actual coins, and that he needed to study Manchu. He began to scour antique markets and dealers for old coins and found retired professors in Taiwan to teach him the language.

“They had great fun with this crazy German who wanted to study Manchu,” he says.

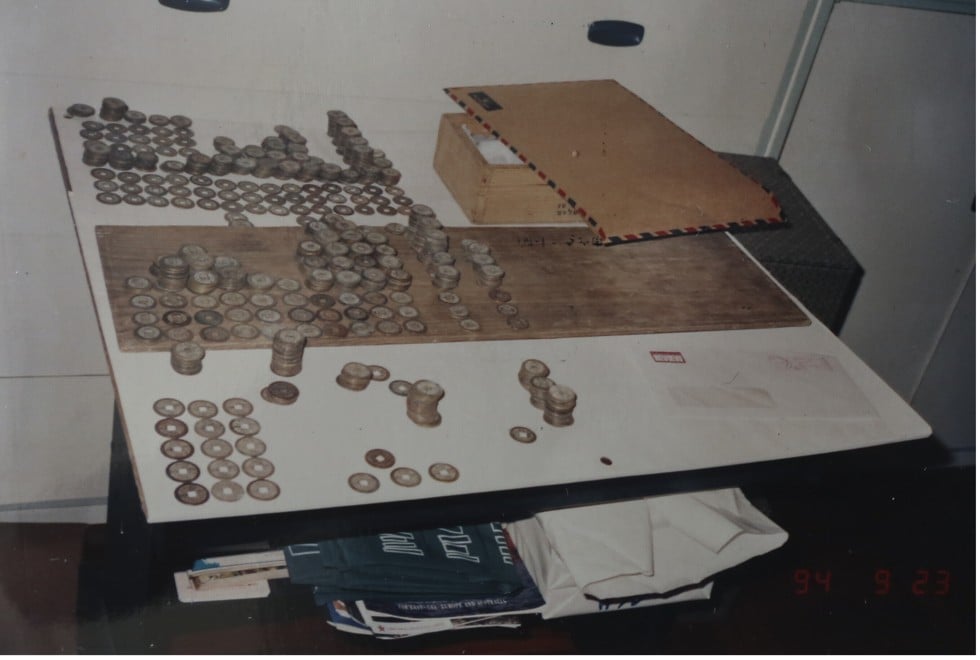

The Qing dynasty produced millions of coins annually, but Burger started his collection with a mere two million. A friend in Hong Kong, Lau Chi-man, imported scrap metal from Indonesia, where Qing cash was in circulation until the Japanese occupation in the 1940s.

“He let me have 70 bags full of coins, each about 100kg,” Burger says. “I could choose whatever I wanted. The rest he used as scrap metal. This was the basis of my collection, and it was 95 to 96 per cent Qing coins.” Lau’s gift was a stroke of luck. “I had enough coins to do what nobody else had done,” Burger says. “Arrange the coins year by year.”

Even with his initial stash, Burger ran into a roadblock with the Qianlong Emperor’s reign, which lasted 61 years, from 1735 to 1796, and during which multiple mints were operated in each province.

“My goal was to write about the whole Qing dynasty, but I needed more information,” he says.

He approached Sinologists around the world, asking where he might find mint archives. Alfred Kaiming Chiu, head librarian of the Harvard-Yenching Library until his retirement in 1964, gave him his first clue, pointing him towards the First Historical Archives.

“The archives are open to serious researchers, so every time I went to Beijing, I asked about mint reports. ‘Oh, we don’t have them,’ the gatekeeper would say. ‘It’s you again, we still don’t have them.’”

Burger made a living in Hong Kong “doing this and that”, teaching German at the Goethe-Institut and writing for the Far Eastern Economic Review. At a dinner party in 1975, he met the daughter of a Taiwanese diamond dealer based in Tokyo, Japan, and in so doing found the woman he wanted to marry. Lucy joined forces with him in a 16-year search for the mint records, which included relentless cultivation of a senior director of the First Historical Archives, Tang Yinian.

Then, in 1996, the perennially resource-starved archives received a windfall that allowed renovations to be conducted. Workers knocked down a wall, and found a room packed to the ceiling with Qing imperial archives. The discovery was comparable to the finding of Buddhist texts in the Mogao Caves, in Dunhuang, Gansu province, in 1900, revolutionising Qing studies at one stroke.

“They found 30 million records,” Burger says, merrily. “First, they had to employ 600 genius professors and sort them out. They were all kinds of administrative records – water works, personnel – over 200 departments. Finally, they had tens of thousands of copies of mint reports.”

Tang sent a telegram. “He told us, ‘Good news, come to Beijing right away,” Burger says.

“I was so happy,” Lucy says. “This guy, he’s German, he’s angry and scolding them.”

It took two years to sort through the mint records, and another six years of research to absorb the contents.

Then began the writing of the book and planning for a centre of Chinese numismatic studies.

Before the discovery of the lost archives, the main Chinese sources on Qing money reported only what the official mints had been ordered to make. But the lost archives included accounting records of every official mint in the empire, including how much cash was produced, the cost of production and where it was distributed.

After completing the monumental task of compiling and arranging, in chronological order, the production of each mint from 1735 to 1911, Burger did two things with the data.

First, he was able to calculate with a high degree of accuracy the total annual cash production across China, and compare it with census-based population records. The result is an index of economic activity, from 18 coins per person at the height of China’s prosperity under the Qianlong Emperor to its depths during the period when the Empress Dowager Cixi ruled and China was deep into its period of national humiliation, the antithesis of President Xi Jinping’s Chinese dream.

By the late 19th century, production ranged between 0.5 to one cash per person annually, which, combined with the runaway devaluation of cash currency against the benchmark value of silver, meant that economic activity had slowed to a crawl.

Second, Burger analysed prevailing annual exchange rates.

The massive devaluation of Qing currency in the 19th century is typically blamed on the opium trade, which was funded in silver imported from Mexico through the Manila galleon trade from 1565. Burger’s microscopic focus on mint data, matched with the most extensive cash collection in existence, tells a different story. Forgeries, both domestic and foreign, undermined the currency as early as the Qianlong reign.

“From the Kangxi Emperor [1654-1722] to Qianlong, soldiers were paid the equivalent of two taels of silver per month in two strings of cash,” Burger says. “From Kangxi to Qianlong, no problem. The exchange rate in Qianlong was always around 925 cash to the tael, which meant that the soldiers needed only 1,800 cash to buy two taels of silver to send home to their families and could keep 200 cash in their pockets. So, with this kind of bonus, the soldiers were happy.

“When they were called upon to conquer a new province, whether Xinjiang or Tibet, they were happy to do so.”

In the last years of Qianlong’s reign, the exchange rate suddenly spiked to 1,200 cash to the silver tael as a result of forgeries by mints originally established by loyalists of the previous dynasty, the Ming (1368-1644), in Vietnam. The forged coins were traded into southern Chinese ports and mixed with legitimate cash. The 75-year-old Qianlong forced government offices throughout the country to buy up the forgeries at scrap-metal prices, and the exchange rate rose to 900 cash to the tael.

“It took two to three years, but it was a successful operation,” Burger says. “Fifteen to 20 years after the first clean-up operation, they should have done it again.”

But they didn’t, and by the end of the reign of the eighth Qing emperor, Daoguang (1820-1850), the exchange rate was over 2,000 in every part of China, reaching a peak of 2,500. And there was no credit system.

Proposals by a reform-minded official, Wang Maoyin, in 1854, to develop a paper currency that could be used as a silver equivalent were rudely dismissed, and the continuing disintegration of the monetary system was a factor contributing to China’s losses against foreign powers as well as the government’s helplessness in dealing with the Taiping rebellion (1850-1864), during which 20 million to 30 million lives were lost.

“It was the largest disaster of the Qing dynasty,” Burger says. “All because they didn’t take care of the money. The officials had only studied the Confucian classics and had no idea about money.

“If you tell that to the historian, they say, ‘No, no, no, it’s all the bad imperialistic British. They sold us opium. Before they took tea for it and not silver, but after Napoleon occupied Spain, they couldn’t get pieces of silver any more and the pieces of eight were cut off.’

“What one can learn from how the Qing dynasty ran its show is that, although they were good book keepers – much better than the British or the Germans – they did a lousy job of making a system of their economy. The Europeans very soon had Adam Smith and, by writing down the theory and challenging it, slowly they had the economy in their grip. The Chinese never did. They had no theory.”

Burger’s own theories remain controversial in China, within the small circle of experts in numismatics. In 2003, the China Numismatic Museum, in Beijing, held a conference on his first book, Ch’ing Cash Until 1735, published in 1975. The assembled experts were incredulous.

“They challenged him,” Lucy says. “Werner asked, ‘Has anyone in this room seen seven tons of coins? Two million coins?’ They were just dead quiet. The curator is still laughing about it.”

Based on his doctoral dissertation, the earlier book used Burger’s massive coin collection to demonstrate the changes introduced each year by each mint in the “mother cash”, which was used to imprint the coins. “They would make them a tiny bit different in order to check on Mint Master Li,” Burger says, referring to measures taken to thwart internal fraud. “If the coins were underweight, they could get him.”

By varying dots and strokes of the writing on each mother cash, the mints also protected against counterfeit currency.

The statuesque Lucy serves as business partner, spokeswoman, collaborator and caretaker, wheeling her chair-bound husband across the stations of his monumental collection. No single element is less than extraordinary.

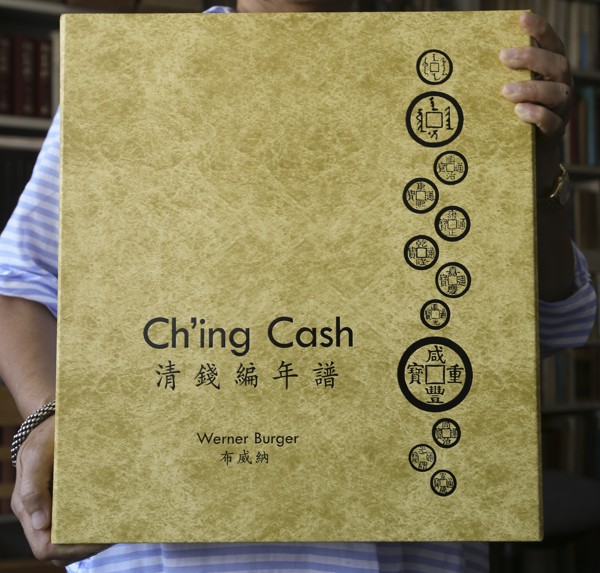

The two-volume Ch’ing Cash, published by the University Museum and Art Gallery, the University of Hong Kong, is not only heavy but large enough, at 37cm x 32.6cm, to demand its own wheelie. Only 1,000 copies were produced, and the price tag of HK$6,000 is enough to discourage casual buyers.

Against a wall are the 60 volumes of mint archives, reproduced painstakingly from the long-lost originals still in Beijing. The printing alone took half a year. “Then I had to read them and digest them, and arrange them sequentially,” Burger says.

The word “cash” – qian or “money” in Chinese – comes from pidgin, a China coast dialect, and derives from the Sanskrit word for copper, karsa. Each emperor provided calligraphy for the mother cash, and while they lack the beauty and accessibility of works of art, the coins provide windows into the social and economic history of the period. Both the China Numismatic Museum and the National Museum of China, also in Beijing, have large money collections, dating from as early as the Western Zhou (1046-771BC), but none have the completeness of Burger’s collection.

“I am the greatest numismatic collector in the world,” he says. And there are none who would contest the claim.

Burger worked with Dr Florian Knothe, director of the University Museum and Art Gallery at the University of Hong Kong, on the book that became Ch’ing Cash. The pair now want to build a studies centre for Chinese numismatics, which would be the first of its kind in Asia.

“The book is key to this,” Knothe says. “It’s the outcome of 40 to 50 years of research. Why is it that there are centres in Europe and the United States that teach numismatics, starting with Greek and Roman coins, but none in Asia? There are collections, but not teaching collections. We think this would be a wonderful opportunity to teach more numismatics in China.”

Paris-Diderot University’s Jankowski says: “If the museum of HKU is able to secure it, [Burger’s] great collection will bring HKU to the front line of numismatic collections, overtaking the British Museum [in London], the Hermitage [St Petersburg], the Bibliothèque nationale [Paris] and the Chinese Numismatic Museum.”

To some, that might seem a bargain.