Life and violent death in Chinatown: Hong Kong-born mob boss Tony Young’s story

The gang leader turned pillar of the community was playing mahjong when he was stabbed to death in Los Angeles in January

Tony Young stepped out of the noodle shop and lit a cigarette.

As he did on many afternoons, he was heading to play mahjong at Hop Sing Tong, a 141-year-old social club in Los Angeles’ Chinatown. But he had a gambler’s intuition that the tiles would not fall his way.

“Help me play a few hands. Lately, my luck has not been good,” the Hong Kong-born Young said to his lunch companion. The friend declined, and Young headed west on the 10 Freeway from Alhambra to downtown LA on his own.

He had barely settled in at a table when a man barged in with a knife, slashing one of the mahjong players across the neck, then turned on Young, stabbing him seven times.

The January 26 slayings shattered the quiet of Chinatown, where Young, 64, had been a fixture for decades, adapting to the changes around him with canny self-assurance.

Recently, he had been sworn in as president of Hop Sing Tong, a red rose pinned to his lapel as journalists from local Chinese newspapers documented the ceremony. At banquets, he cut a distinctive figure with his shaved head, winsome grin and well-cut suits. When foreign dignitaries visited Chinatown, he was in the receiving line.

But there was a side to Young that dated back to a more troubled time. The FBI had pursued him for years, convinced he was a leader of the notorious Wah Ching gang, implicated in an armed robbery and at least two murders. He escaped an extortion charge after a key witness fled the country. He was suspected of plotting to assassinate the Taiwanese president. But only one case against him, for financial crimes, stuck.

Like many reputed gang bosses, he was an elusive quarry. He always insisted he was just a businessman.

His violent death, though, brought his old life bubbling back to the surface, calling up long-buried stories from the Chinese underworld and leaving some to wonder whether his past had finally caught up with him.

“He exceeded his sell-by date by 35 years,” says Ben Lee, a retired Los Angeles police detective who worked the Chinatown beat.

Joe Hoe “Tony” Young arrived in LA from Hong Kong when he was 16. He had trouble learning English and dropped out of Belmont High School, finding a calling elsewhere – in the glamour and fast cash of the gang lifestyle.

At five feet and six inches tall and weighing 110 pounds, Young was slightly built, with a mane of black wavy hair. His nickname was Mut Joe, “sweet date” in Cantonese.

In the early 1970s, Chinatown had three cinemas and a population of youngsters who, like Young, had moved to LA after the United States government loosened restrictions on Asian immigration. Young and his friends congregated in Alpine Park or took in kung fu flicks while puffing on cigarettes, often without paying for their tickets, according to Lee, the retired detective.

Young travelled to other cities where the Wah Ching, or Chinese Youth, had ties. By his early 20s, he was known to law enforcement on both sides of the Pacific.

In March 1974, Hong Kong police officers sent an urgent teletype to American law enforcement authorities. They had Young in custody and suspected his involvement in an armed robbery in San Rafael, California, where a Hong Kong film crew had been held up by four masked, Cantonese-speaking men. They would have to release Young soon unless the Americans planned to arrest him, they said in the message.

Young eventually went back to California and does not appear to have been charged with the San Rafael robbery.

Around this time, a feud between the Wah Ching and the rival Joe Boys, which began over control of gambling, drugs and protection rackets, was spiralling into a series of deadly revenge shootings, one of which nearly killed Young.

At the Jade Palace nightclub in San Francisco, in September 1976, four men fired pistols into the crowd, hitting Young in the chest and head. He was hospitalised in critical condition.

The feud reached a bloody climax a year later, when Joe Boys members sprayed gunfire around the dining room of the Golden Dragon restaurant in San Francisco. No Wah Ching members were hit. Instead, five people with no gang ties were killed, and 11 were wounded.

After his brush with death, Young rose in the hierarchy and was eventually named the head of the Wah Ching’s LA chapter. By then, he had traded the casual look of his youth for a blazer and dress shoes, exuding a nice guy image.

“He was a very cunning person. He knew how to show respect,” Lee says. “He would never be disrespectful to a police officer.”

Young was not shy about his gang affiliation and bragged to Lee about his position as a dai lo, or elder.

But Young was difficult to pin down. His only criminal convictions in the 1970s and ’80s were for drunken driving and smoking in a cinema. He was never charged with a violent crime.

“If I could have put handcuffs on him, I would have,” Lee says.

In June 1982, four young men entered a gold commodities brokerage in Monterey Park, in Los Angeles County, and asked for money, hinting that saying no would lead to “some trouble”. The company’s president, William Liu, reported the incident to the FBI and wore a wire the next time he met with one of the men, Johnson Woo. The recording captured Woo demanding a US$1,500 monthly payment.

When Liu asked if he would be beaten up for refusing, Woo responded: “We’ll see how it goes.”

Federal prosecutors believed the scheme was orchestrated by Young and other Wah Ching members. Young and Woo were charged with extortion.

As the trial approached, Liu left the country and did not return, forcing prosecutors to drop the case against Young. Based in part on the FBI recording, Woo was convicted and sentenced to six months in prison.

Years later, Liu told an FBI agent that he did not testify against Young because he feared for his life.

“Tony had done such a good job for so long with intimidating potential witnesses and other gang members that it was difficult to make a case against him,” says former federal prosecutor Christopher Johnson.

Word of Young’s criminal exploits travelled as far as Washington. Concern about Asian gangs was at its height in the late ’80s and early ’90s, and Congress periodically held hearings on the issue. A chart presented at one hearing showed Young at the top of the LA Wah Ching structure, four lieutenants fanned out beneath him.

In March 1987, after Young’s car was shot up by a member of a rival gang, a local casino dealer was beaten savagely while Young watched from his car, a congressional report said.

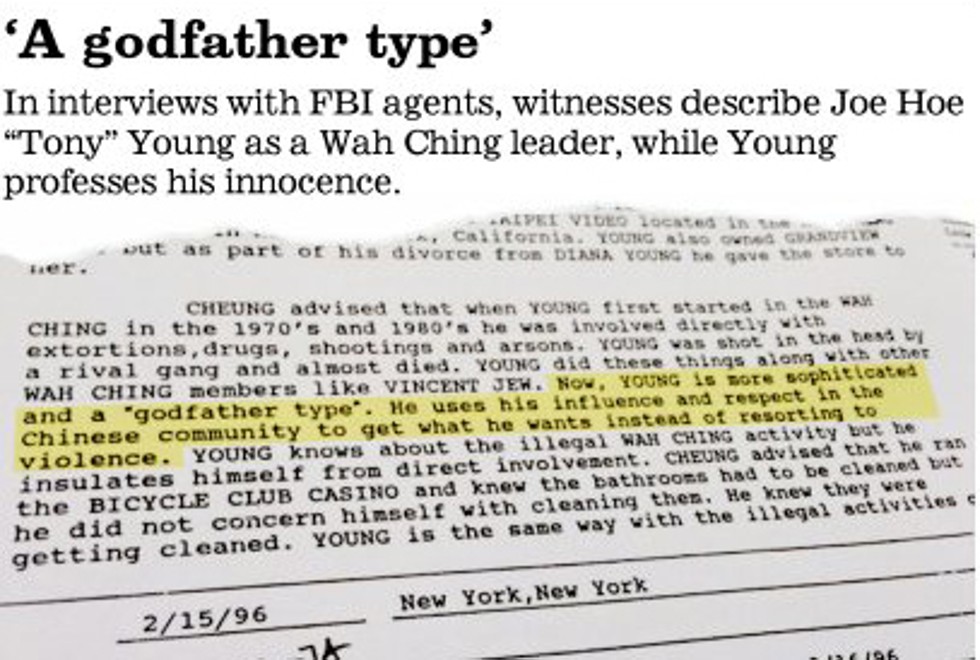

Young ran the Wah Ching’s gambling empire, which focused on pai gow, a game popular with Asian immigrants. He also monopolised the lucrative Chinese-language entertainment industry.

If the owners of Chinese video companies did not fall in line, they suffered consequences. One local video distributor reluctantly sold the rights to her business after her property was damaged and she received a phone call from Young, according to a congressional report.

When Chinese entertainers visited southern California, Young asked Chinatown business owners to sponsor the concerts at up to US$2,000 a pop, according to Hollman Cheung, who ran the Bicycle Club Casino in Bell Gardens. Saying no was not an option, Cheung told the FBI in 1996.

Young was a “godfather type”, Cheung said, who used “his influence and respect in the Chinese community to get what he wants instead of resorting to violence”.

On his 39th birthday, Young met with FBI agents at a Marie Callender’s restaurant in Monterey Park to tell his side of the story. He insisted he had quit the Wah Ching long ago, after he had been shot at the San Francisco nightclub. The FBI was hounding him, looking for crimes that did not exist, he said in a December 10, 1991, interview. He described himself as a smart businessman who made US$12,000 a month.

But according to an FBI informant, Young was still very much a dai lo.

The following year, Young presided over a swearing-in ceremony at a Chinatown temple. Surrounded by statues of Buddha, 15 to 20 Wah Ching initiates sat around a long table, the air heavy with incense. They cut their fingers with needles and let the blood drip into a bowl of water, pledging allegiance to their gang elders as Young watched from a corner of the room, the informant told agents.

Around this time, younger men began challenging Young’s leadership. As factions fought for supremacy, gunfire erupted at several locations, including a San Gabriel nightclub where a Wah Ching member was killed by one of his own.

In May 1993, LA County Sheriff’s deputies investigating the violence served search warrants at 38 locations, including Young’s Monterey Park house.

Young again declared his innocence, this time in an interview with the Los Angeles Times, saying he had been unfairly targeted by law enforcement for years.

“How can they prove that?” he asked angrily. “I hate extortion. Never! I hate extortion against our own people.”

In the end, Young’s downfall mirrored that of legendary Chicago gangster Al Capone.

Buried in Young’s financial records, FBI investigators found evidence of criminal wrongdoing. In his applications for real estate loans, Young had submitted tax returns listing higher incomes than he reported to the Internal Revenue Service. In one instance, Young applied for a loan with a tax return showing US$139,663 in income when he had only reported US$40,663 to the federal government. Young’s 1992 bankruptcy filing also conflicted with tax documents.

In 1995, Young was charged with two counts of lying to a financial institution and two counts of bankruptcy fraud. Instead of surrendering, he boarded a plane to Asia.

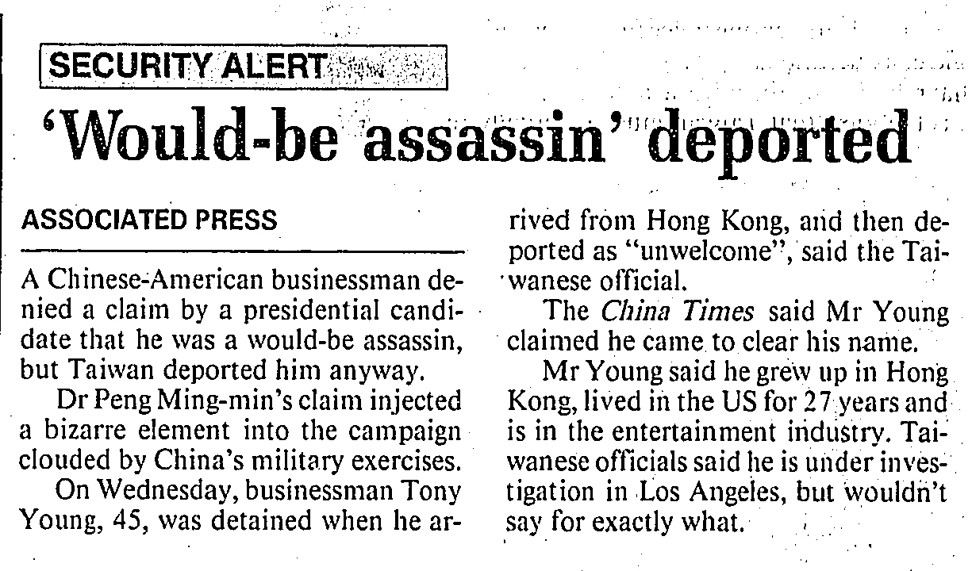

There, FBI agents believed, he got mixed up in a plot to kill Taiwan’s then president, Lee Teng-hui, who was running in the island’s first democratic presidential election. FBI agents tipped off Taiwanese authorities, who arrested Young at Taipei airport on March 19 and put him on an LA-bound flight.

Young was convicted of two counts of lying to a financial institution and sentenced to 13 months in prison.

In a court declaration, the lead FBI agent, James Glynn, outlined a criminal career spanning more than two decades, from the San Rafael armed robbery to the alleged assassination plot. Included in Glynn’s recounting was Young’s suspected involvement in a murder in San Francisco and one in Taiwan, though he was not charged with the killings.

For Glynn, putting Young behind bars for financial crimes was more than a consolation prize. It was a chance to “take the head off the snake”, he said recently.

After Young got out of prison, his influence in the Wah Ching appeared to wane. A new generation of dai los had risen. Their turf was not Chinatown but the San Gabriel Valley, the new epicentre of Chinese influence and the destination of choice for wealthy immigrants from Taiwan and Hong Kong.

By February 2001, the Wah Ching was at war with two other Chinese gangs, the Red Door and the Four Seas. On a recording captured by a confidential informant, Young could be heard speaking in Cantonese during negotiations between the rival gangs in Monterey Park and Arcadia, according to Dennis Lao, an FBI agent on the case.

“Tony Young was one of the older guys who didn’t want a gang war,” says Lao, who retired last summer.

The younger Wah Ching leaders proceeded anyway. The violence that followed included the mistaken killing of an ally in Monterey Park.

Thirteen Wah Ching members were charged with federal crimes, including murder in aid of racketeering and distributing marijuana and ecstasy. Six of them were also charged with planning an armed robbery at an Alhambra brothel whose owner had refused to pay US$3,000 a month in protection money. The prosecutions disrupted the Wah Ching’s leadership structure.

By the time Tom Yu began investigating Asian gangs for the LA County Sheriff’s Department in 2008, groups like the Wah Ching tended to be “headless”, lacking an organisation chart like the one Young once topped.

“It’s ad hoc, loosely organised – not ‘Who’s your dai lo?’” Yu says.

In 2016, the Sheriff’s Department disbanded its Asian gang task force. The Wah Ching is no longer a concern for LA police.

“They’re not active. Nothing regarding that gang is standing out,” says Captain Marc Reina, of Central Division, which includes Chinatown.

Sometime after the failed peace negotiations, Young moved to Shanghai, where he ran a bar.

When he returned to LA in around 2008, he gravitated towards Hop Sing Tong and soon became a prominent member.

Housed in a three-storey building with a pagoda-style red-tile roof, the club occupies a prominent spot in Chinatown’s central plaza. Its double doors are usually propped open, providing a glimpse of old men shuffling mahjong tiles or perusing Chinese newspapers. Once central in violent wars against other Chinese tongs, Hop Sing Tong has long since become a quiet backwater.

In recent years, after teetering on the verge of obscurity, Chinatown has begun to reinvent itself. A gourmet hamburger stand occupies the corner across from Hop Sing Tong. At the Nashville hot chicken joint down the street, hipsters brave a line stretching nearly a city block.

Young reinvented himself, becoming a respected community leader.

Peter Ng, executive director of the Chinatown Service Centre, was aware of Young’s past. But Young seemed “very open, direct, not the kind of person who would trick you, someone you could count on”, says Ng, who likened Young’s return to that of the biblical prodigal son – lost and now found.

He was a changed man. He was no longer the one who creates the problem. Instead, he was doing all the right things to help people.

Young often referred Hop Sing Tong members to Ng’s centre for help finding jobs or sorting out immigration problems – a function that tong leaders had always performed, along with doling out emergency cash, in keeping with the tong’s mission as a mutual aid society.

Young achieved such stature that the Taiwanese government gave him an honorary community liaison title, the alleged assassination plot either forgiven or forgotten. On a visit to LA in 2015, then-Taiwanese president Ma Ying-jeou was photographed shaking hands with Young, the two men gripping and grinning in front of an image of the Hollywood sign.

“He was a changed man. He was no longer the one who creates the problem,” Ng says of Young. “Instead, he was doing all the right things to help people.”

Wayne Ng, the friend who shared Young’s last meal, says he met Young working at an underground casino in New York’s Chinatown in the 70s. At the time, both were members of the Wah Ching, which, Ng insists, was a mutual aid society, not a criminal gang.

In those days, Young had a keen sense of chivalry and would not stand for the strong preying on the weak, Ng says. According to Ng, a few Wah Ching members sometimes bullied restaurant owners into forking over a few hundred dollars.

“Not me and Tony,” Ng says.

Decades later, when the two friends got together for lunch or coffee, they rarely reminisced about their youth, Ng says. After all he had been through, Young felt fortunate to be leading a quiet life.

“He was really happy. He was 60-something and still walking around Chinatown,” Ng says.

Like so many immigrants before him, Vinh Dao came to Hop Sing Tong looking for help. He asked for money to pay for an impounded car but was not happy with the amount he received.

Several days later, as Chinatown was gearing up for the Lunar New Year holiday, the 36-year-old returned, according to police detectives. After a solitary lunch at the nearby Plum Tree Inn, he sneaked out the back door without paying, restaurant workers said.

It was only a few yards to Hop Sing Tong, where Young and other retirees were gathered around a mahjong table. At five feet, three inches and 136 pounds, Dao was not physically imposing, but he had served prison time for a fatal stabbing. Dao again demanded US$400 for his vehicle impound fees, according to detectives. He then attacked 64-year-old Kim Kong Yun with a six-inch knife, penetrating deep into the man’s neck, clear through the vertebra and spinal cord, according to an autopsy report. Yun’s wife said he was a retired casino worker who spent most days at Hop Sing Tong playing mahjong and had known Young since they were teenagers. When Young came to his friend’s defence, Dao slashed him in the neck, chest, back, abdomen and arms.

Young slumped onto his left side next to a staircase, blood from his wounds pooling around him.

The news spread quickly in Chinatown and in law enforcement circles. Was it an unsettled score from decades ago?

But there was no need to delve into Young’s past.

Dao was arrested a day later and charged with both killings. A police news release described him only as a long-time member of Hop Sing Tong who spent his “days at the club playing mahjong and visiting with friends”.

Five days later, deputy medical examiner J. Daniel Augustine dissected Young’s body, starting with a Y-shaped incision from both shoulders down the middle of the abdomen. A police officer stood by to witness the autopsy.

Augustine proceeded methodically through the mouth, neck and chest, coming across nothing abnormal except for the stab wounds. Then, he found a bullet lodged in Young’s left second rib.

It was covered with rust.

Los Angeles Times