2022 in books: Colleen Hoover’s bestselling year, Bob Dylan and Bono memoirs, self-help queen Brené Brown goes viral, Salman Rushdie stabbed

- 12 months ago romance and young-adult novelist Colleen Hoover was a word-of-mouth sensation. Now she’s everywhere you turn in the book world

- Brené Brown coolly dissected human emotions, Matthew McConaughey, Bob Dylan and Bono wrote – and recorded – memoirs; Salman Rushdie was attacked on stage

In any other year, there would have been a long line of candidates competing for 2022’s biggest literary story.

Robert “J.K. Rowling” Galbraith returned with The Ink Black Heart (Sphere, 2022), and Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing (Corsair, 2019) was given a substantial second wind courtesy of Reese Witherspoon’s movie adaptation. Jenny Han’s “The Summer I Turned Pretty” trilogy (Penguin, 2010-2012) received a similar commercial boost with Amazon’s popular series.

The Bullet that Missed (Penguin, 2022), the third novel by British television personality turned crime writer Richard Osman, continued the momentum generated by 2020’s record-breaking debut, The Thursday Murder Club.

Another writer who kept selling into 2022 was Taylor Jenkins Reid, with her Golden Age of Hollywood confessional The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo (paperback Simon & Schuster, 2021).

And if you thought nothing could top James Patterson’s collaboration with former United States president Bill Clinton, along came Patterson’s collaboration with Dolly Parton: Run, Rose, Run (Century, 2022).

The outpouring of support that followed included a defiant rush to purchase The Satanic Verses (Vintage, 1989), which became a bestseller all over again.

The remainder of publishing’s extraordinary year can essentially be summarised in two words: Colleen (and) Hoover. Unheard of 12 months ago, the 43-year-old American romance and young adult author has become a commercial phenomenon. No fewer than five Hoover titles feature in Amazon’s end-of-year top 10.

By October, Hoover was approaching 9 million sales for the year, according to The New York Times, which meant her books were more popular than the Bible.

But any number of Hoover’s previous 24 novels and novellas are riding the coattails of this success, including 2014’s Ugly Love and Verity (2018, all Simon & Schuster).

It’s been a while since sales charts were dominated by a single author quite to this extent. You have to rewind a decade or more to the reigns of George R.R. Martin, E.L. James, Stieg Larsson and Stephenie Meyer in the 2000s and 2010s.

Crime writer Tess Gerritsen on her creative burst in Covid-19 lockdown

While Hoover’s work is more realistic than all of these, there are comparisons to be made. Her dark romance fusion of violence and tenderness joins the dots most obviously to James and Meyer, whose Twilight series provides a blueprint for Hoover’s love-hate triangles. But what really links all five blockbusters is the power of word-of-mouth devotion.

Hoover, like James, began by publishing her own work and then spent a decade winning a devoted group of readers, the self-proclaimed CoHorts. The media may trumpet the role TikTok played in Hoover’s all-conquering year, but this legion of fanatics was already well established, competing with one another over who cried the most while reading her prose.

Brace yourself. Hoover has only just begun, and 2023 will doubtless provide more mega-hits and the inevitable film adaptations.

Prize winners

Set in 1990, Karunatilaka’s second novel is audaciously narrated by a photographer who, as the action starts, has just been murdered. As his body sinks through the waters of a lake, his mind provides a caustically satirical take on Sri Lanka’s recent history.

In his wonderful Booker victory speech, Karunatilaka said he hoped Seven Moons would soon be read “in a Sri Lanka that has understood that the ideas of corruption and race-baiting and cronyism have not worked and will never work”.

Ernaux, whose works also include A Man’s Place (1983) and A Woman’s Story (1988), was praised by the Nobel committee for “the courage and clinical acuity with which she uncovers the roots, estrangements and collective restraints of personal memory”.

Guangzhou-born Malinda Lo left China aged three when her family relocated to Colorado, in the US. Four decades later, she has collected three major American literary awards in the space of 12 months.

Lo’s novel Last Night at the Telegraph Club (Dutton Books for Young Readers, 2021) won 2022’s Asian/Pacific American Award, a year after carrying off the Stonewall Award and the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

Lily Hu, the narrator of the novel, breathes much-needed new life into the coming-of-age story. Growing up in 1950s San Francisco, Lily is refreshingly free of the usual tropes of teenage rebellion, instead falling in love with another girl while learning what it means to be Asian-American in a post-war US.

Children’s literature

Children’s books are arguably the most intriguing sector in publishing. On the one hand, there are a mind-boggling number of exciting new titles that reflect the increasingly diverse experiences of young readers.

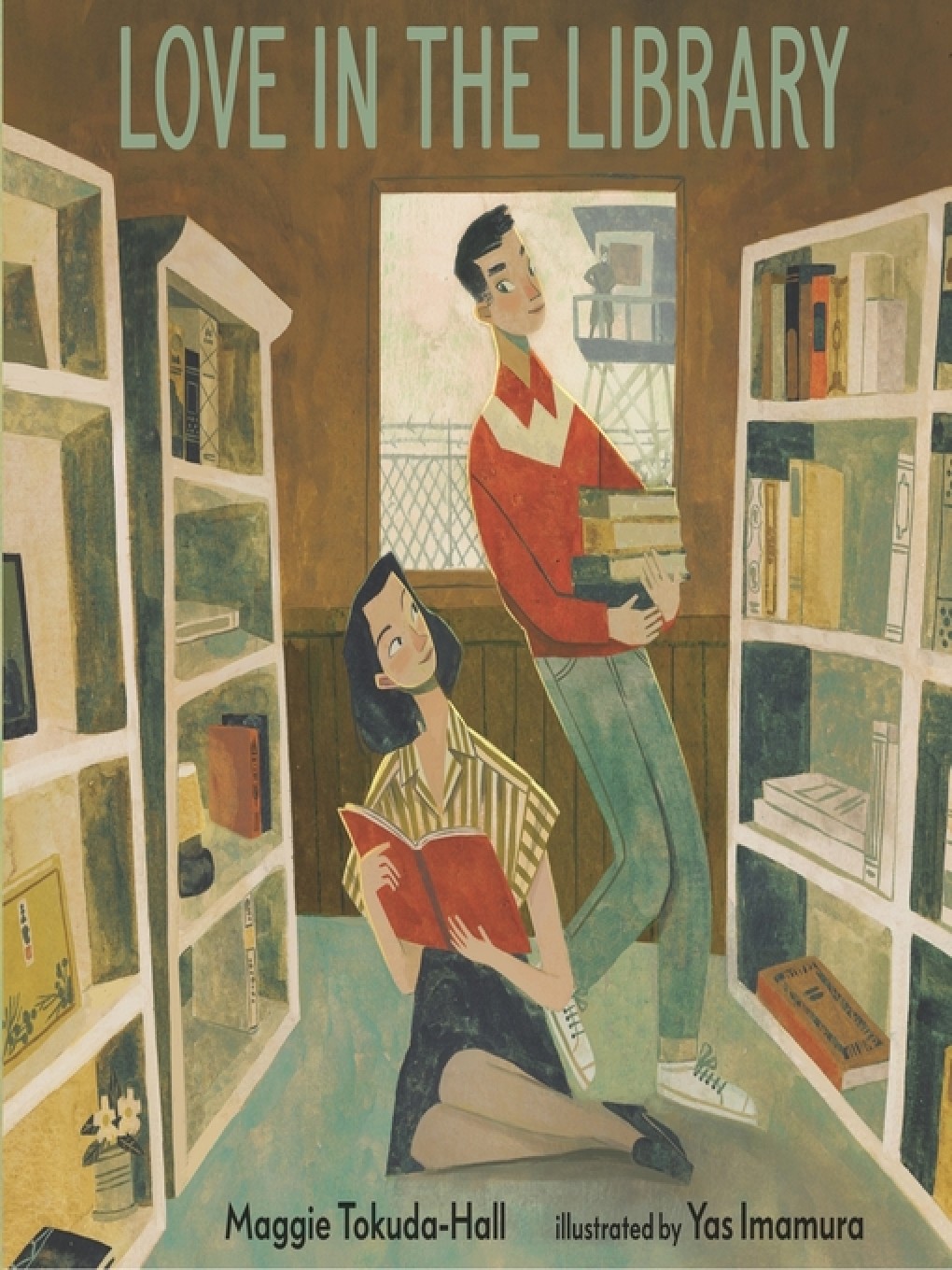

Take Love in the Library (Candlewick, 2022), written by Maggie Tokuda-Hall and illustrated by Yas Imamura. Who would have guessed that a romance set in a US prison camp would make a stirring children’s picture book?

Tokuda-Hall’s heroine, Tama, works in the small and underfunded library of Idaho’s infamous Minidoka camp. Struggling to accommodate herself to these grim surroundings, Tama meets George, whose love of books and later Tama as well helps her recognise her own feelings of anger, injustice, sadness and desperation.

The story is powerful enough on its own, but the fact that Tama and George were based on Tokuda-Hall’s own grandparents adds an undeniable frisson.

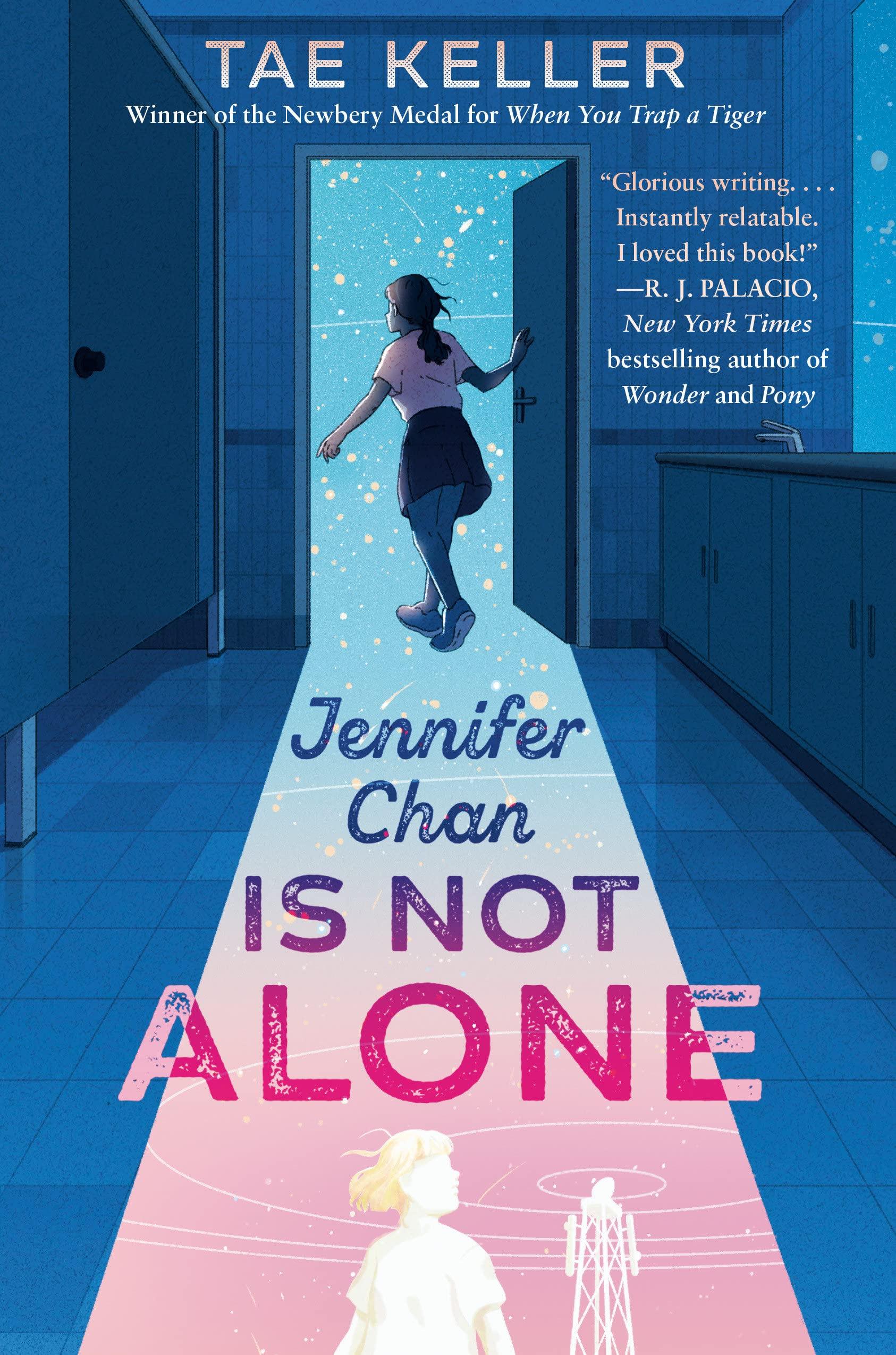

Tae Keller’s Jennifer Chan is Not Alone (Random House Books for Young Readers, 2022) achieves similar success with the vexed question of childhood friendship. The titular Jennifer is the new girl in Norwell, a town in Florida unused to anyone new, girl or otherwise.

The fact that Jennifer is also Chinese-American and believes in aliens does not endear her to the close-minded and predominantly white natives of “Nowheresville”, as our narrator, Mallory “Mal” Moss, calls it.

This leaves Mal in a bind. Does she celebrate the long-overdue arrival of another Asian-American (Mal is half Korean), or does she placate her conservative schoolmates? Then Jennifer runs away, forcing Mal to confront her complicity with bullying and racism, and later her own Asian heritage and the true meaning of friendship.

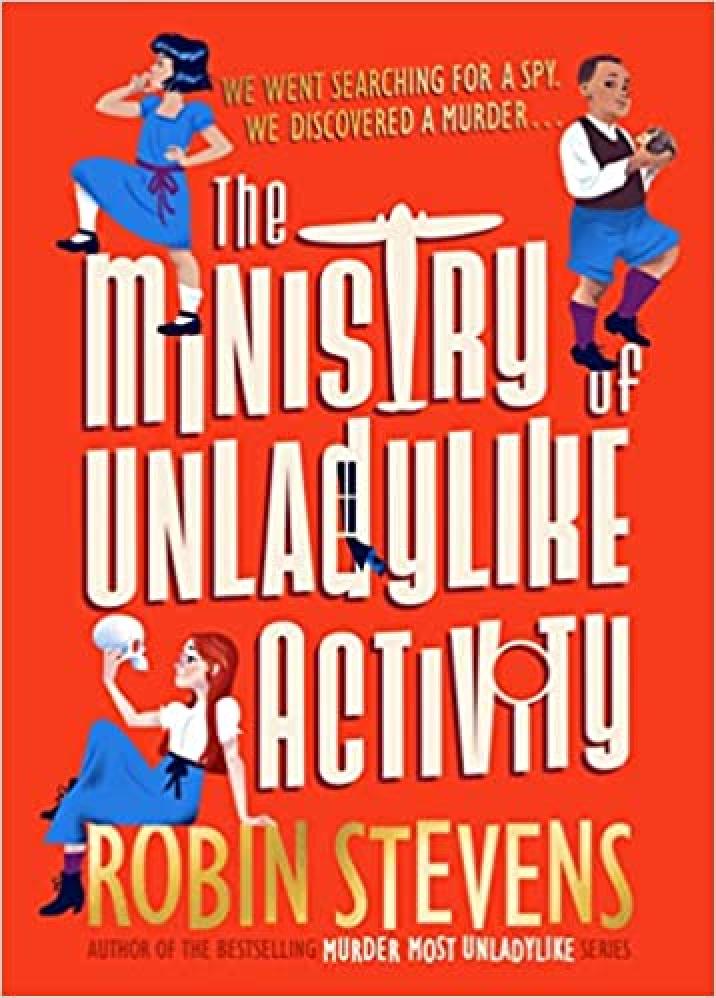

Hong Kong readers have more reason than most to enjoy Robin Stevens’ new crime novel, The Ministry of Unladylike Activity (Puffin, 2022). Stevens’ heroine, May Wong, introduces herself like this: “I am ten years old (nearly eleven) and I have become a spy in order to save the world.”

Born and raised in Hong Kong, May finds herself trapped in England by the outbreak of World War II. Sent to Deepdean boarding school, she follows in the footsteps of her older sister, Hazel, in more ways than one. Hazel, as fans of Stevens’ bestselling series will know, was a teenage detective extraordinaire.

May’s talents tend more towards espionage. Recruited by the top-secret Ministry of Unladylike Activity, she runs away from Deepdean and finds herself investigating a possible German spy ring at Elysium Hall. Stevens’ lively, sharply plotted thriller is aimed at younger readers, but fans of all ages will find it hard to resist her Agatha Christie-Enid Blyton update.

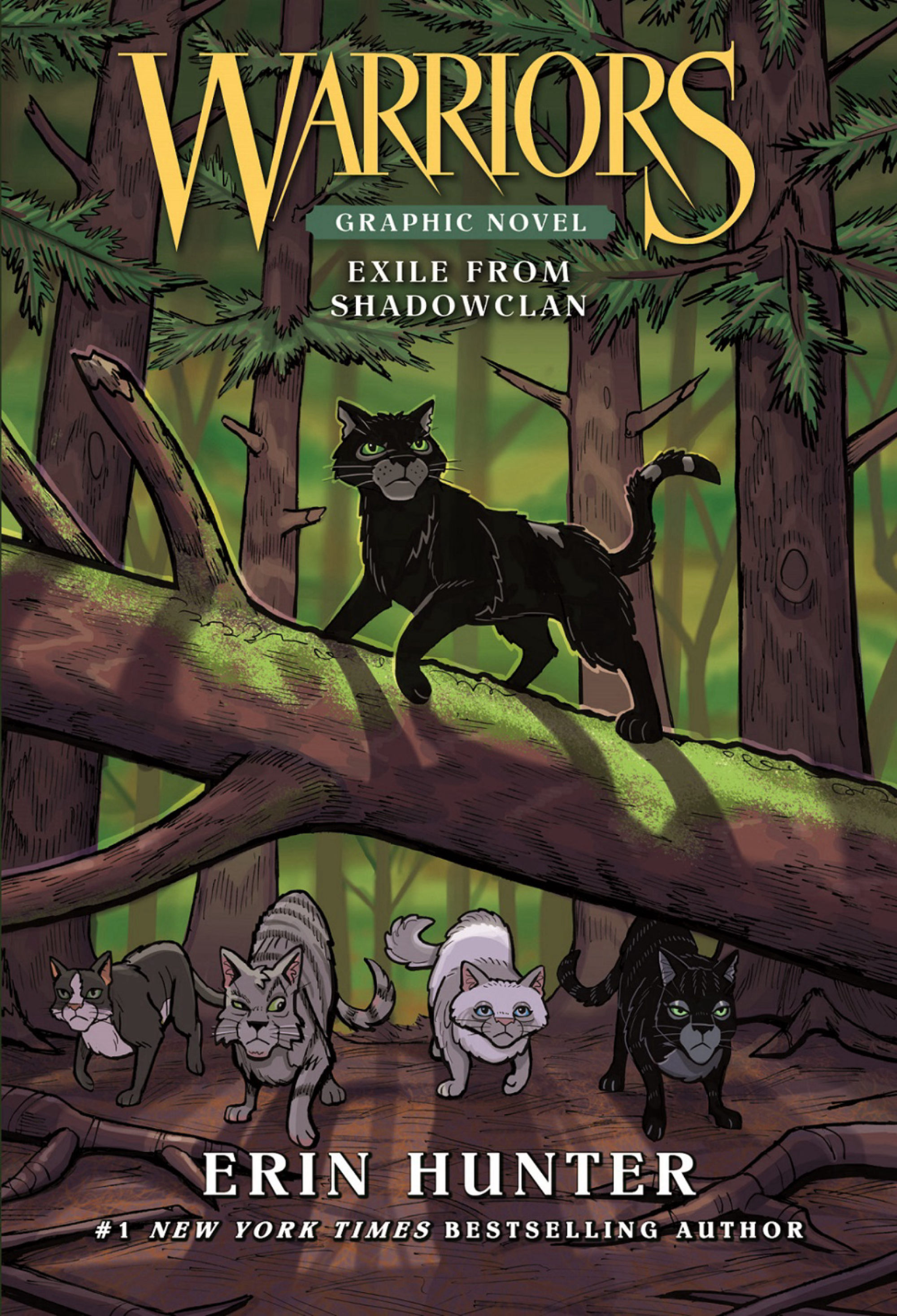

Personally, I will always remember 2022 as the year of Warrior Cats. This ever-expanding adventure series written by Erin Hunter (in reality several authors) follows several generations of wildcats as they hunt, fight rival clans, fall in love, raise families and even confront death.

My eight-year-old daughter has read hardly anything else for the past few months. Not only has she caught up with new series Starless Clan (HarperCollins, 2022), which reunites readers with favourite characters who have ascended to the feline afterlife, she is composing her own Warrior Cat fan fiction. Colleen Hoover beware.

For all this impressive diversity of new moods and subject matters, children’s literature continues to be dominated by a small but perfectly formed pack of masterpieces. Of course, adult literature has its share of classics, too. But how many appear in end-of-year bestseller charts – not just once or twice, but without fail?

There probably hasn’t been a year since Eric Carle first published The Very Hungry Caterpillar (Puffin) in 1969 when this peerless board book hasn’t outsold the most overhyped new thriller, crime novel or groundbreaking literary fiction.

The same goes for Oh, the Places You’ll Go (HarperCollins, 1990), Dr Seuss’ final book but arguably his most popular: its popularity as a gift for school leavers means it eclipses Seuss’ other great works, such as 1957’s The Cat in the Hat.

Other hardy perennials to elbow between 2022’s most successful new titles include Jeff Kinney’s Diary of a Wimpy Kid (Puffin, 2007), Rowling’s Harry Potter series (Bloomsbury, 1997-2007), Charlie Mackesy’s The Boy, The Mole, The Fox and the Horse (Ebury, 2019) and that ultimate literary lullaby, Goodnight Moon, by Margaret Wise Brown (HarperCollins, 1947).

Non-fiction

More than one commentator noted the dearth of non-fiction books in bestseller lists during 2022. Perhaps readers were fed up with reality after three years of Covid-19 and lockdowns; perhaps they were simply too busy reading Colleen Hoover.

Whatever the reason, a few notable works did manage to lodge themselves in people’s bookcases, Kindles and audiobook devices.

The media platform has yet to be invented that Brené Brown cannot monopolise. Whether she is delivering a TED Talk, podcasting, lecturing, broadcasting on HBO or writing an oldfangled book, America’s expert in human emotions gave new meaning to going viral in 2022.

Published at the end of 2021, Atlas of the Heart (Vermilion) examines rocky moments in the human condition – uncertainty, peer pressure, crisis, disillusion, failure, emotional pain – and proposes solutions, or to use a Brenéism “places we go” to recover, regroup, “self-assess” and move on.

It is sometimes far too easy to disparage even superior self-help books such as Atlas of the Heart or the bestselling British equivalent, Dr Julie Smith’s Why Has Nobody Told Me This Before? (Michael Joseph, 2022). But the very popularity of these titles pays eloquent testimony to the struggles so many of us feel, whether as parents, partners, workers or children.

If that doesn’t convinced you, perhaps the fact that James Clear’s guide to time management, Atomic Habits (Random House Business, 2018), gave Hoover a run for her money might.

Few books, fiction or non, enchanted quite like Ed Yong’s An Immense World: How Animal Senses Reveal the Hidden Realms Around Us (The Bodley Head, 2022). Yong harnesses the latest scientific research in an attempt to understand how animals experience the world.

What, Yong wonders, is it like to see like a brittle star, whose whole body is an eye (although not at night)? Why would a vampire bat drink blood but turn up its nose at a bowl of sugar? Why does a blue-throated hummingbird sing songs it cannot hear? What does danger smell like to an elephant?

A staff writer at The Atlantic magazine, he won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Covid-19, and has earned many other awards and accolades for his blogs explaining cutting-edge science for the layperson.

One might argue that Frank Dikötter has been doing something similar for China, explaining its long history and complex present for readers across the world. The prize-winning author of Mao’s Great Famine (2010) returned this year with China After Mao (Bloomsbury, 2022), completing what Dikötter calls “The People’s Trilogy”.

Part three narrates China’s transformation from the underachiever of the 1970s into the 21st century’s leading superpower. Whether he is pondering which came first, Party politics or economic policy, or navigating the slippery relationship between power, productivity and protest, Dikötter unpicks this most tangled web with admirable clarity.

Audiobooks

Audiobooks have always divided opinion. Some readers love to lose themselves in the voice of their favourite narrator or, as happens more frequently, A-list actor “performing” a favourite book. For others, this feels more like an invasion against the voice we all hear in our heads while reading the written word.

In other words, one listener’s treasure is another listener’s trash. Doubtless Quentin Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2022) is a fantastic account of 1970s cinema, but listening to Tarantino’s voice, for even the two chapters he could be bothered to record, was more than my ears could take.

One book, if “book” is the right word, that made perfect sense of the format this year was Inside Voice (Pushkin Industries, 2022) by filmmaker Lake Bell. Part-podcast, part multimedia experiment, the recording is Bell’s way of exploring her “Obsession with How We Sound”.

Among the questions she addresses are: why do some voices make us laugh; what do voices tell us about class, gender and geography; and what role does how we sound play in falling in love? Bell’s guests include Malcolm Gladwell, Drew Barrymore, Pam Grier and Jeff Goldblum.

Music is provided by Christopher Bear, of acclaimed band Grizzly Bear.

What would Bell make, I wonder, of the A-list actors who “performed” their own books this year? Matthew McConaughey’s Greenlights (Headline, 2022) is a memoir inspired by the diary he has kept for 35 years.

I have no idea how well McConaughey’s anecdote about saving an apparently dead parrot reads on the page, let alone his recollection of naughty dreams or even the poem he wrote on first seeing his wife, Camila Alves: sample lines, “Springtime and salty./ A squaw and a queen./ She was no virgin but she wasn’t for rent./ A mother to be.”

But it all benefits from the grainy drawl of McConaughey’s voice, and the sincerity of his tone.

The same is certainly true of Viola Davis’ Finding Me (Coronet, 2022). Another memoir, it is less concerned with laying pseudo-spiritual nuggets on your eardrums, à la Greenlights, and more with tracing Davis’ own rise from poverty in Rhode Island via Broadway to Hollywood.

Education, alienation, racism and shame recur time and again, as does hope, self-belief and learning how to develop natural-born talent.

Another icon who published a much-hyped book, but like Tarantino had mixed feelings about recording the audio version, was Bob Dylan.

The Philosophy of Modern Song (Simon & Schuster Audio, 2022) airs Dylan’s thoughts about 66 rock ’n’ roll standards, winding from crooners such as Blue Moon and Volare to punk-pop classics like “London Calling” and “Pump It Up”.

Dylan reads about half the chapters, and some of these only halfway. Judging by the heavy echo of his voice, he was either in church or sitting in the world’s largest kettle. Dylan is assisted by some very starry A-listers indeed, including Jeff Bridges, Oscar Isaac, Helen Mirren and Renée Zellweger.

The curious result matches the curious eclecticism of the book: you never quite know whether Bridges is about to rumble like thunder or Mirren is going to impersonate the late Queen Elizabeth.

Best of all of these is Bono reading his autobiography, Surrender (Penguin, 2022). For once that verb “perform” isn’t an empty publishing cliché. Bono reads with verve, emotion and great humour, a mood heightened by the witty and not intrusive use of music and sound effects. As with Elton John’s 2019 memoir, Me, you can enjoy spending time with Bono even if his music isn’t your cup of tea.

In memoriam

As 2022 draws to a close, it is a good moment to remember some of the literary talents we lost this year.

Two-time Booker Prize winner Hilary Mantel died in September, aged 70. Her place in the literary universe seems assured thanks to her superb Wolf Hall trilogy.

Jack Higgins, who died in April aged 92, never came close to Mantel in terms of literary recognition, but sales of more than 250 million books offered some compensation. His thrillers such as A Prayer for the Dying (HarperCollins, 1973), To Catch a King (HarperCollins, 1979) and most famously The Eagle Has Landed (Penguin, 1975) helped to make the 1970s and ’80s a golden age for the airport blockbuster.

Scientist and environmentalist James Lovelock is best known for the Gaia hypothesis, which he developed through a series of hugely popular books, including Gaia: A New Look at Life on Earth (Oxford University Press, 1979).

Lovelock argued that Planet Earth is a self-regulating system whose survival depends upon the way natural organisms interact with their inorganic surroundings. By turns influential and controversial, the theory helped shape modern environmentalism, above all its warnings about climate change, greenhouse gases and the destruction of our oceans.

Not long before he died, in July aged 103, Lovelock predicted he was in the last 1 per cent of his life. Living up to his reputation as an ecological doomsayer, he added that something similar could be said about our own planet.

This year also witnessed some notable bookish anniversaries. It was 200 years since the English poet Percy Bysshe Shelley drowned off the coast of Italy, aged just 29. Admired by some for the lyrical beauty of his verse and by others for the strident outrage of his political prose (which advocated among other things revolution and vegetarianism), Shelley (or Xuelai, 雪莱, as he is known in China) is a favourite of President Xi Jinping.

Exactly a century after Shelley’s death, the world witnessed one of the great artistic annus mirabilis. Among the modernist masterpieces written and published during these 12 months were: James Joyce’s Ulysses, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, Virginia Woolf’s Jacob’s Room, Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies, Ryūnosuke Akutagawa’s short story In a Bamboo Grove, which inspired Akira Kurosawa’s 1950 film Rashomon, and C.K. Scott Moncrieff’s first English-language translation of Proust’s À la recherche du temps perdu.

Christmas

Finally, since Christmas is rapidly approaching, can I suggest a couple of festive books? Almost any question about Christmas, great or small, is answered by Bill Bryson in his small but perfectly formed audiobook The Secret History of Christmas (Audible Studios, 2022).

Christmas wouldn’t be Christmas without Charles Dickens in some form or other. None other than Hugh Grant narrates Ebenezer Scrooge’s transformation from misanthropic miser to all-singing, all-dancing one-man welfare state.

Wisely, Grant doesn’t overdo the voices, which does lend evil Ebenezer an unlikely raffish charm.

Lastly, if it’s a cocktail of crime and Christmas you’re after, then Arthur Conan Doyle’s 1892 Sherlock Holmes drama The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle hits the spot. I recommend BBC Radio’s peerless dramatisation starring Clive Merrison and Michael Williams (The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes, BBC Digital Audio, 2017), which adds a dash of goodwill and a touch of poignancy.