What can America, land of ‘zombie malls’, learn from Hong Kong’s shopping malls?

- ‘Zombie malls’ signal the demise of an American cultural icon, and while hailed by some, architecture critic Alexandra Lange laments the loss of social spaces

- Hong Kong malls thrive because, in contrast to their American, ‘anti-transit’ counterparts, they are well integrated with local transport and communities

Meet Me by the Fountain by Alexandra Lange, pub. Bloomsbury Publishing

This has been greeted with undisguised joy by a new generation of urban thinkers who prefer the street to the shopping centre.

Not architecture critic Alexandra Lange.

‘Does this look third world to you?’: US woman’s Malaysia TikTok goes viral

Her book, Meet Me by the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall, makes the case that malls have long been underappreciated, overlooked and misunderstood, and their decline could have serious social consequences.

The book has received a flurry of attention since its recent release. “I really appreciate it that people are taking it seriously,” says Lange from her home in Brooklyn, New York.

As with her previous book, The Design of Childhood (2018), she has delved into a topic that has been ignored in architectural discourse, exploring it with an omnivorous approach that blends design criticism with social, cultural and architectural history.

“The beginning of the book is very urban and architectural, but beginning in the 1970s and ’80s, the mall is really a cultural icon and it gets up in all these pop culture settings, especially TV and movies,” she says.

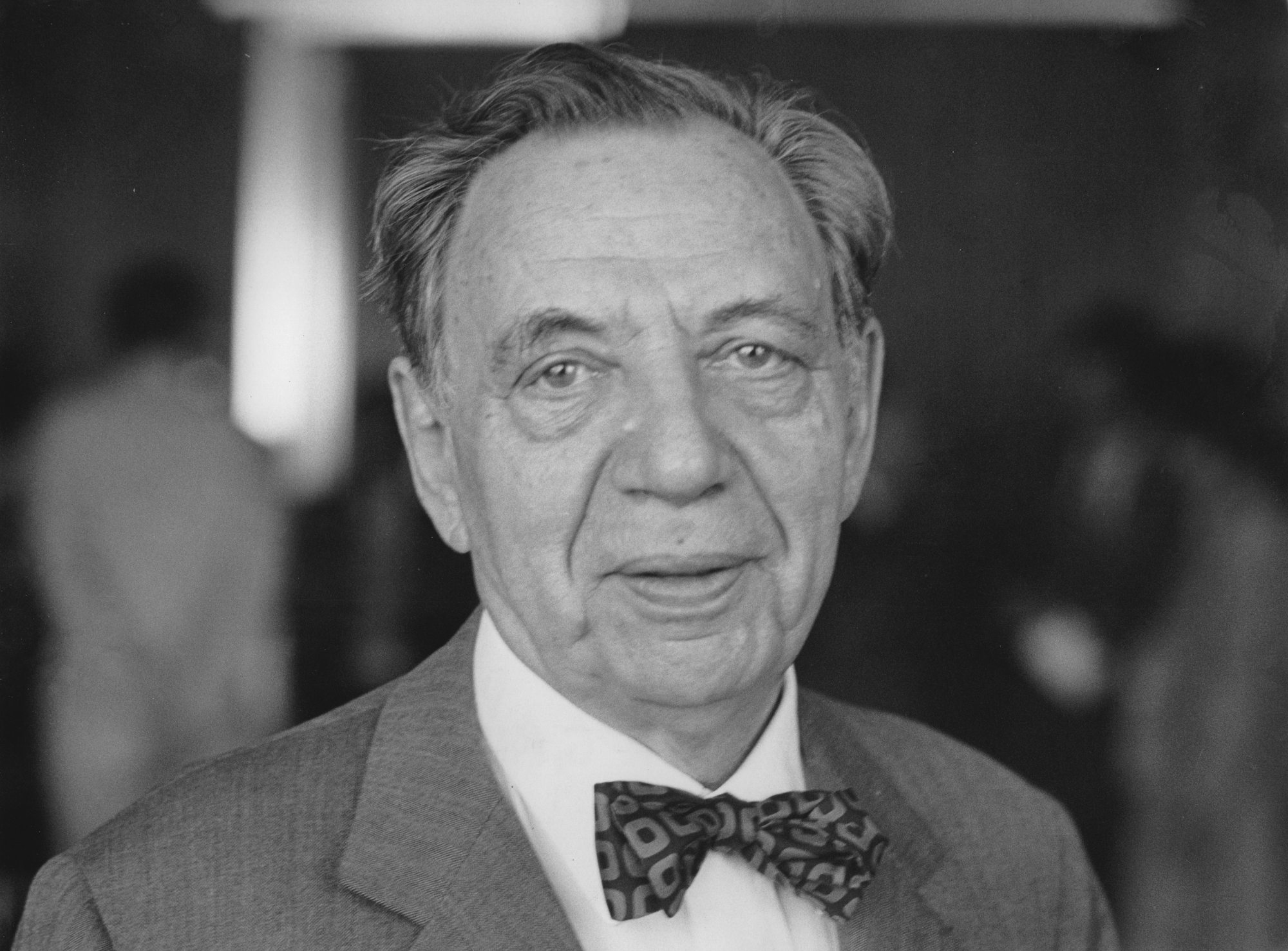

The mall has its roots in the 19th-century arcades of cities such as London and Paris. But its modern-day form was the brainchild of Austrian architect Victor Gruen, who fled the Nazi invasion of his home country and moved to the United States in 1938.

Gruen was dismayed by the disjointed sprawl of mid-century American suburbia – “a garishly advertised parade of filling stations, hot dog stands, department stores, snack bars, liquor stores, supermarkets, chain stores, used-car lots, and funeral parlours”, as he described it – and set out to create an alternative.

Working for a Detroit department store chain, Gruen proposed a new kind of retail development that served as a kind of enclosed town centre. The result was the Northland Center, an open-air complex that opened in suburban Detroit in 1954.

Those early malls were boxy and inward-looking, saving their architecture for interior spaces. In an era of urban decay in the US, they were seen as safe, controlled and convenient alternatives to downtown areas or traditional high streets.

As a high-school student lurching toward freedom, the mall gave me somewhere to go

There was also an undercurrent of racism in their conception, part of the system of anti-black laws and policies that underpinned suburban growth in mid-century America.

“As malls began to spread countrywide in Southdale’s wake, the next decades would demonstrate how that control made shopping easier and more seductive for some and compounded the segregation of others – often at the same time,” writes Lange.

But malls continued to evolve through the years, turning into all-encompassing social spaces where you could spend an entire day hanging out. Atria with natural light and elaborate fountains became the suburbs’ equivalent of the town square, a place for early morning mall-walkers and teenage “mall rats” alike.

“Arcade games replaced sock hops, food courts replaced tea parties,” writes Lange.

The author grew up in Durham, North Carolina, where malls named Northgate and South Square served as her teenage stamping grounds. “As a middle-schooler lurching toward personal style, and as a high-school student lurching toward freedom, the mall gave me somewhere to go,” she writes.

Things have changed in the past two decades. The steady rise of e-commerce, the 2008 global financial crisis and the sheer overabundance of retail space in the US have conspired to end the golden age of the American mall. Dead malls – along with half-empty “zombie malls” – litter the landscape.

Lange makes the case that this is more than just a problem for the retail economy. “In the rush to dance on the mall’s grave, we risk treating it as only a disposable consumer object and neglecting the basic human need that it answered,” she writes.

Shopping has to be connected to people’s lives

With no fountain or food court where they can gather, suburban kids are more isolated than ever, trapped in car-dependent sprawls, leading social lives through online spaces more than physical ones.

“I think it would be better if kids can hang out with their friends in person,” says Lange. “I wish cities wouldn’t make it so hard.”

They are densely built, vertically oriented and closely linked to public transport, housing, community facilities and offices.

By contrast, Lange notes that, “historically, malls in the US have been anti-transit”. And the design and management of many malls have ignored their social and cultural importance.

The handful that continue to thrive act more like the most successful Asian malls, integrated into their surroundings, making them an indispensable part of the larger city.

“One of the big messages of my book is that commercialism in a vacuum doesn’t work,” she says. “Shopping has to be connected to people’s lives.”

Though its focus is resolutely American, Meet Me by the Fountain opens the door to investigations of the mall in other countries and cultural contexts.

“They changed the way we live,” says Lange. The mall is dead; long live the mall.