Daughter of the Moon Goddess author Sue Lynn Tan on her reimagining of a Chinese myth and reaching for a dream

- In coming-of-age novel Daughter of the Moon Goddess, Hong Kong-based Malaysian author Sue Lynn Tan imagines the goddess Chang’e has a daughter, Silver Star

- She draws connections between her own adolescence and Silver Star’s and says: ‘You put a piece of yourself in a novel. To have it rejected is terrifying’

Daughter of the Moon Goddess by Sue Lynn Tan, pub. Harper Voyager

“When you have a dream that you want very much, sometimes you feel scared to reach for it. Because if it doesn’t happen, it is very crushing. There is a special type of pain involved with that.”

Sue Lynn Tan is describing the long, bumpy road that culminated in the publication of her excellent first novel, Daughter of the Moon Goddess. Like all aspiring writers, Tan was plagued by insecurity and discouraged by rejection. But if anything characterises her conversation today, it is that most invaluable ability to keep going even through the toughest and saddest of times.

“You never know how life is going to turn out,” Tan tells me towards the end of our chat. It is a motto that can be applied equally to her literary career and her life in Hong Kong. “I never thought I would end up living here,” she explains.

Tan had been working in Singapore when her boyfriend landed a job in Hong Kong. Even when she relocated, she didn’t believe they would stay longer than a couple of years. “We still have all our things in storage in Singapore,” she says with a laugh.

Nine years later, and Tan is married with two young sons, and Hong Kong is very much home. “It has really grown on me. There is so much natural beauty. The mountains. The temples. And the food! I have really found it quite inspiring in terms of writing.”

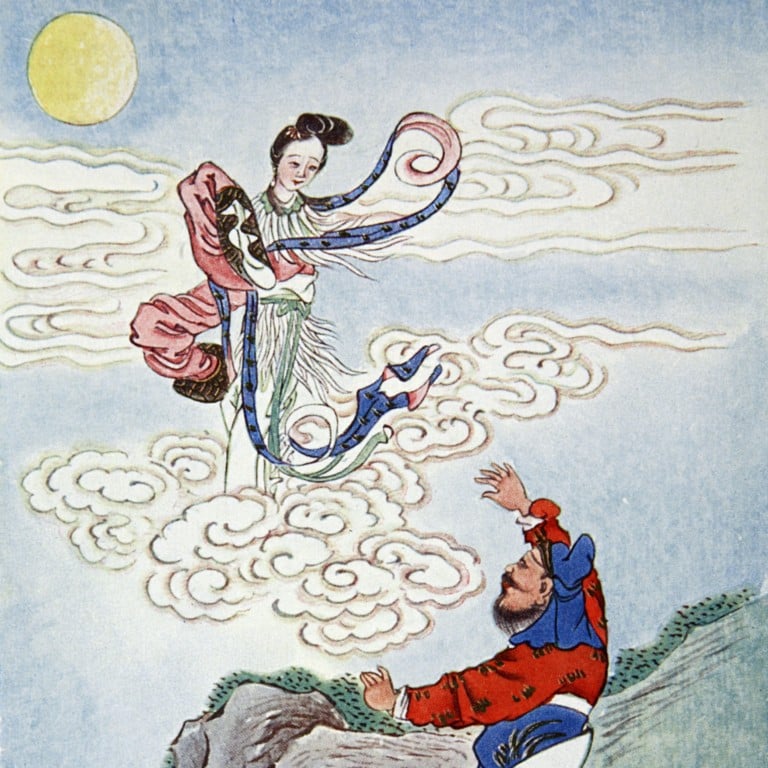

Which brings us to the next unexpected part of her story: Daughter of the Moon Goddess. The story reimagines the myth of Chang’e, the mortal who took up residence on the moon. “There are many legends about my mother,” states Xingyin, Chang’e’s daughter and the heroine of Tan’s narrative.

In most versions, Chang’e falls in love with Hou Yi, a brilliant archer who saves humanity by shooting down nine of the 10 suns that are burning Earth to a crisp. His reward – the elixir of immortality – proves to be a curse when he is granted only a single helping. Unable to imagine eternity without Chang’e, he refuses the drink. Unlike Chang’e herself, tragically enough.

This is the point, Tan says, where the myths really begin to differ. “In some versions Chang’e drinks the elixir to save it from thieves. In another version, Hou Yi becomes a tyrannical king and Chang’e drinks the elixir to save her subjects. Another one basically says she wants to become a goddess. Which is perfectly understandable quite frankly!”

I am a firm believer that it is better to try and fail than to wish and wonder. I want to know that I tried.

Whether Chang’e was selfish or noble, Tan always found the legend slightly wanting. “What if there was another reason she took the elixir – and not just for herself? What if there was someone else she loved as much as her husband?”

Enter Tan’s major innovation: Xingyin, whose name translates as “Silver Star”. The ingenious and deeply moving twist is that Chang’e drinks the elixir to save her baby daughter’s life during an agonising labour.

The price is the unyielding fury of the Celestial Emperor and Empress and the need to keep Xingyin’s identity a secret. Years later, when the still-vengeful empress begins to suspect the truth, Xingyin is forced to run – or fly on a magic cloud – for her life.

Her ensuing adventures are a beguiling mixture of romance, battles, fantastic beasts and a quest to free her mother. “Let’s put it out there,” Tan says when I ask what she and her heroine have in common. “Xingyin is far more magical, amazing and exciting than I could ever be. I wouldn’t want to fight a nine-headed water serpent. I didn’t really think of myself as her.”

And yet, the longer we talk, the closer their respective coming-of-age stories appear to be. Tan, like Xingyin, left home at a young age, swapping Kuala Lumpur for a less than celestial London. Both learn self-sufficiency by navigating new cultures, confronting strange creatures (racists in Tan’s case, most without nine heads) and learning to distinguish genuine friends from two-faced foes.

Both young women are capable students, even when the subject was not to their liking. “Don’t laugh, but I studied finance,” Tan says. “I’m from a traditional Malaysian family. It was expensive to study and I wanted to make sure my parents were happy with my choice of degree. I was terrible at finance though.”

We have almost reached the deepest connection of all: family and grief. In the same way that Xingyin is defined by the loss of both parents, so Tan’s life was changed by the death of her father.

“It was very long ago. I was still very young. It was unexpected. When something like that happens when you are very young, it jolts you into realising that life is very unpredictable – very fragile but also very precious. You start thinking about what’s important in life. I am a firm believer that it is better to try and fail than to wish and wonder. I want to know that I tried.”

These are phrases that Xingyin repeats regularly throughout Daughter of the Moon Goddess: “I would set my mother free. I did not know how, but I would try with everything that was in me”; “it would have been far worse not to have tried”; “A fierce gladness burst through me that regardless of the outcome, I had tried my best.”

The idea is just as important for Tan herself. “I used to be on the wish and wonder scale. I think over time I have moved to the other side: ‘Take all your shots at me. I’m going to give it a go.’” This is easier said than done, especially where writing is concerned.

“When you write you make yourself vulnerable. You put a piece of yourself in there, maybe without knowing it. To have it rejected or to be made to feel that you’re not good enough is terrifying and actually makes you feel very bad.”

How did Tan keep going? “What I tell people is you have to really want it. You have to really believe in it.” She pauses. “It’s OK to feel miserable. It’s OK to cry it out. Or have a glass of wine. But then you just have to pick it up and do it again.”

Daughter of the Moon Goddess pays eloquent testament to this philosophy. And it’s just the start. Tan is finishing a sequel, and her thoughts are already turning to a new adventure. For the moment, she simply hopes readers will enjoy the story as much as she did.

“You hear so much about mortality right now. The book does talk about death, but I wanted to write a happy story that would sweep people away to a place of wonder and enchantment for a few hours. I hope that is also relevant during these times. A story that is uplifting and with hope.”