Author Jhumpa Lahiri on why writing in Italian is like ‘falling in love’

- English exposed her Bengali parents’ vulnerabilities while Italian gave her ‘a real and new sense of quiet’

- The Pulitzer-winning writer is one of the star guests at this year’s Hong Kong International Literary Festival

“There is zero spontaneity in life.”

Jhumpa Lahiri is telling me about her disorienting return to work at Princeton University, where the acclaimed writer is director and professor of creative writing. “We teach everything online, which is strange and frustrating and exhausting. We have no choice.”

There are compensations. “I am actually in an abandoned library. It is one of the few positive developments of Covid. The campus is literally abandoned.” This in turn leads to concern for the “hundreds of thousands of young people who have no option but to move forward with their intellectual lives”. The class of 2020 was meant to include Lahiri’s son, Octavio, who was due to start university this year but is instead “stuck at home with us”.

I basically only write when I am in Italy. When I’m [in America] it is very hard for me to feel like a writer

The 53-year-old was also in Princeton when the pandemic began. “It was very depressing as the reality settled in. I did very little writing,” she says.

Are writers better placed than others to deal with lockdowns? “What is really lacking for true creative work is the contrast to the solitude. I have no problem spending time by myself. I always have, but with the knowledge that I could walk out of the door at any time and engage with the world. The sad thing here is there is no world to engage with any more.”

Life, however, brightened over the summer. “I moved back to Rome, which was great. That was back when I thought, with a lot of others, that the worst was behind us.”

The mention of Rome brings us, more or less, to the reason for our conversation. Lahiri is one of the star guests at this year’s Hong Kong International Literary Festival: she will be talking to Chinese-Irish writer Yan Ge about her decision to write solely in Italian. “I basically only write when I am in Italy. When I’m [in America] it is very hard for me to feel like a writer. I try but it is not very successful.”

Lahiri has gone on record as saying the infatuation began during a holiday in Florence in 1994. And yet she tells me she was ready to fall in love with the language long before. “I used to dream that I was speaking Italian before I could. Sometimes I have prophetic dreams.”

The relationship continued as a long-distance flirtation. Some language lessons in Boston, a few more in New York, and then Brooklyn. But Lahiri didn’t go all the way with Italian until she uprooted her life and moved to Rome to immerse herself not only in the Italian language, but Italian literature, art and culture. This buongiorno was also a “so long” to English, which she decided, privately at first, would no longer be her first language as a creative writer.

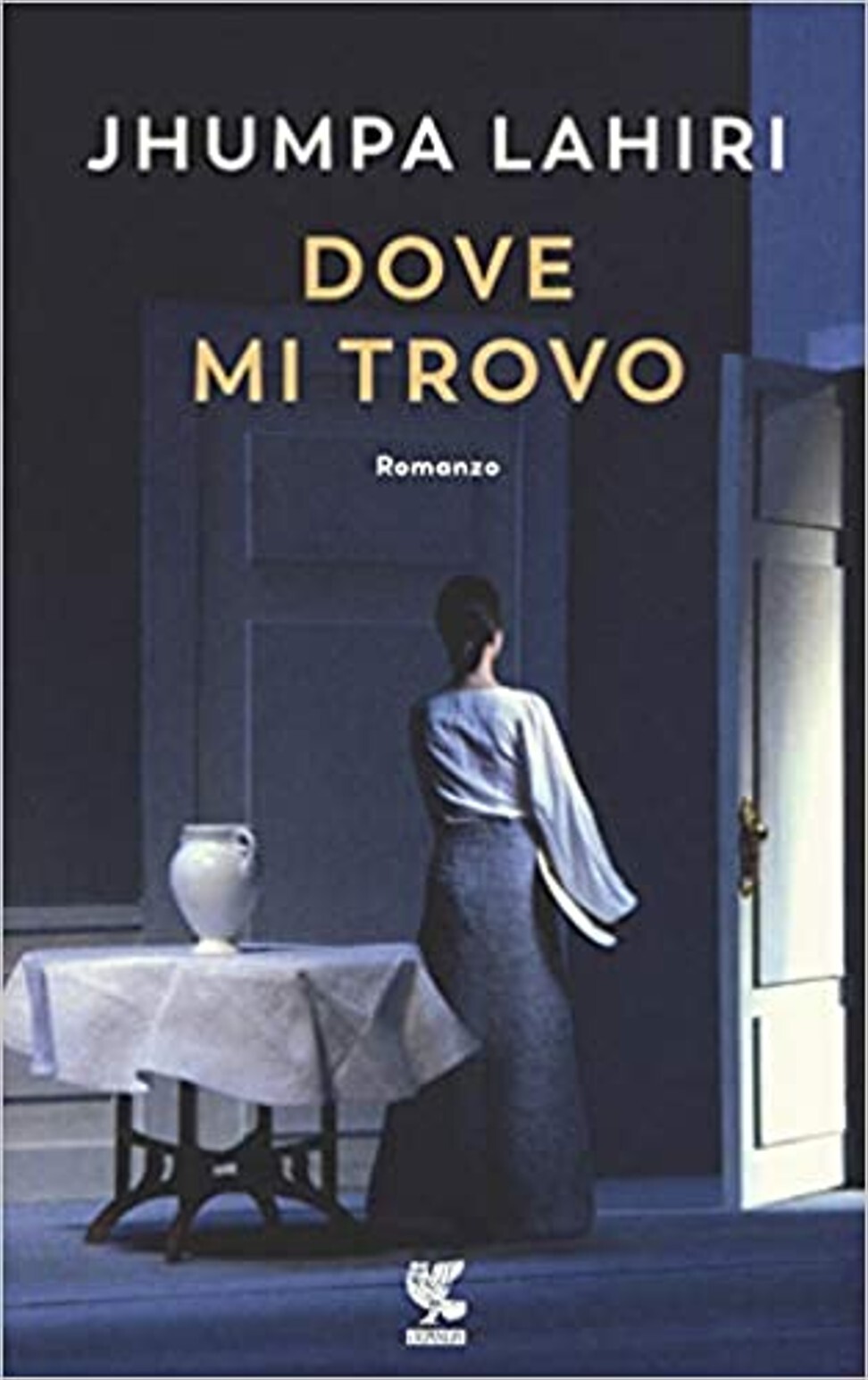

Jhumpa Lahiri wants us to be able to judge a book by its cover

When Lahiri went public about this in 2015, it caused waves even by her own impressive, headline-grabbing standards. Here was a writer who won the Pulitzer Prize with her first book, 1999’s Interpreter of Maladies, and whose writing so impressed the judges of 2008’s Frank O’Connor Award (the world’s most valuable story prize) that they didn’t bother producing a shortlist; they simply named Unaccustomed Earth the undisputed champion.

Did the response to the switch surprise her? “A little bit. I sensed people were grumbling and thought that it was frivolous or foolish. People would come up and say, ‘I am so disappointed in you.’ I could see panic in their eyes when I said that I was committed to a path that was inspiring and stimulating me, and moving me in new directions.”

Lahiri’s new direction has been endlessly dissected, and it is refreshing to hear her speak for herself. Indeed, speaking for herself was a reason for the change. “The idea of choosing a language is very powerful. Choosing an identity that isn’t given to you or forced upon you.

“It’s a creative choice, an intellectual choice, a personal choice. But it’s not a matter of trading one language for the other. It’s about creating distance between myself and English to understand it better, to understand why I have such an antagonistic relationship with it.”

Born in London in 1967, Lahiri moved to the US in 1970. She compares her family’s arrival in Rhode Island to a Martian landing (inspired by Ennio Flaiano’s 1954 short story A Martian in Rome, included in her excellent Penguin Book of Italian Short Stories).

“When I read that story, I did think I’m like the Martian. But to be honest, I have felt that my whole life. When I was a little girl in America, my family was the Martian family. Everyone else was staring at us and wondering who we were and why we did things the way we did. There was that mix of fascination and apprehension. I’ve never known any other feeling.”

What lay at the heart of all this ambivalence was language. “I was terrified to speak with my teachers. I was very scared to interact in a language that I never heard in my home.” Whereas Lahiri spoke English at school, it was Bengali with her family: her parents came from the Indian state of West Bengal.

“I don’t think it was until I moved into Italian that I stopped to think about my relationship with English, how little I trusted the language and the people who spoke in English. That experience marked me.”

You can only fall in love with something you don’t know. You know it by loving it

What proved even more unsettling was the impact on Lahiri’s relationship with her family. “There was the sudden, psychological complication of realising that you have surpassed your parents. That’s very strange for a child to experience – to realise I spoke English so much better than they did. They relied on me so heavily for it. This is typical in immigrant families. You are constantly translating for your parents, speaking for your parents. They give you the phone and tell you to talk to the person on the other end. You realise your parents’ vulnerabilities all the time.”

Italian was empowering, in part, because it was free of these associations. But Lahiri was also liberated from constraints caused by her phenomenal literary writing in English. “If you are lucky enough to become a writer, you are aware, even if you follow it very loosely, what the public is saying about what you are trying to do. The noise is always there. Italian gave me a real and new sense of quiet.”

Five years on, this quiet has resulted in Lahiri’s first Italian-language novel Dove Mi Trovo (Where I Am), and its English version, Whereabouts, also her first English-language self-translation. The titles, aptly enough, refer both to the stories and their storyteller, who found a new direction, paradoxically, by deciding to get lost.

“I was looking for a place where I could feel a sense of total isolation, in a good way that sparks creativity. Where you are left to your own resources, and that very exciting dimension of being half in the dark. It’s like falling love. You can only fall in love with something you don’t know. You know it by loving it.”