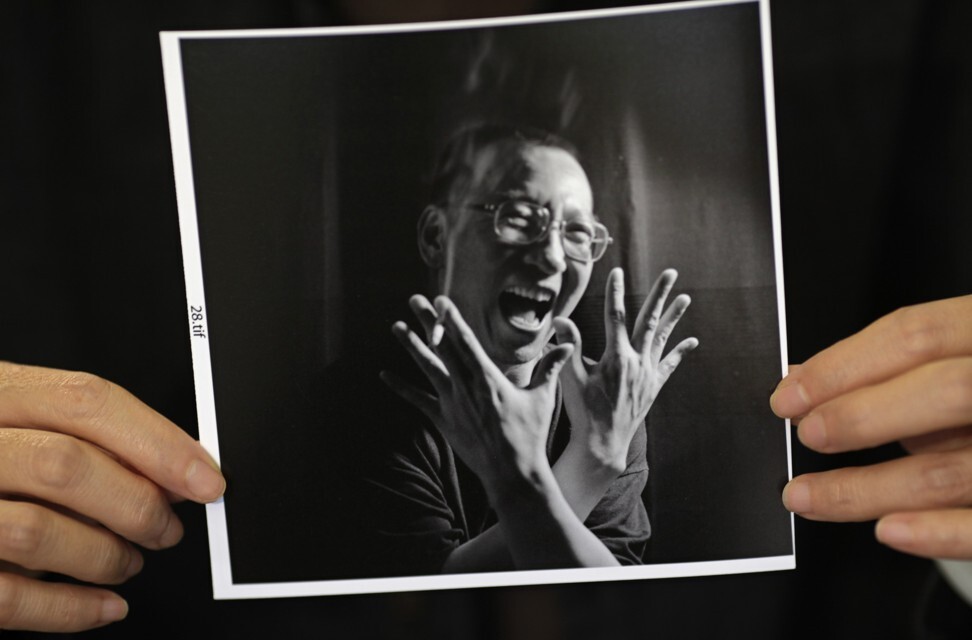

Review | The Journey of Liu Xiaobo reveals how Chinese dissident went from ‘dark horse’ to Nobel laureate

- Friends and colleagues recall the late Nobel Peace Prize winner and a fearless champion of human rights and democracy in China

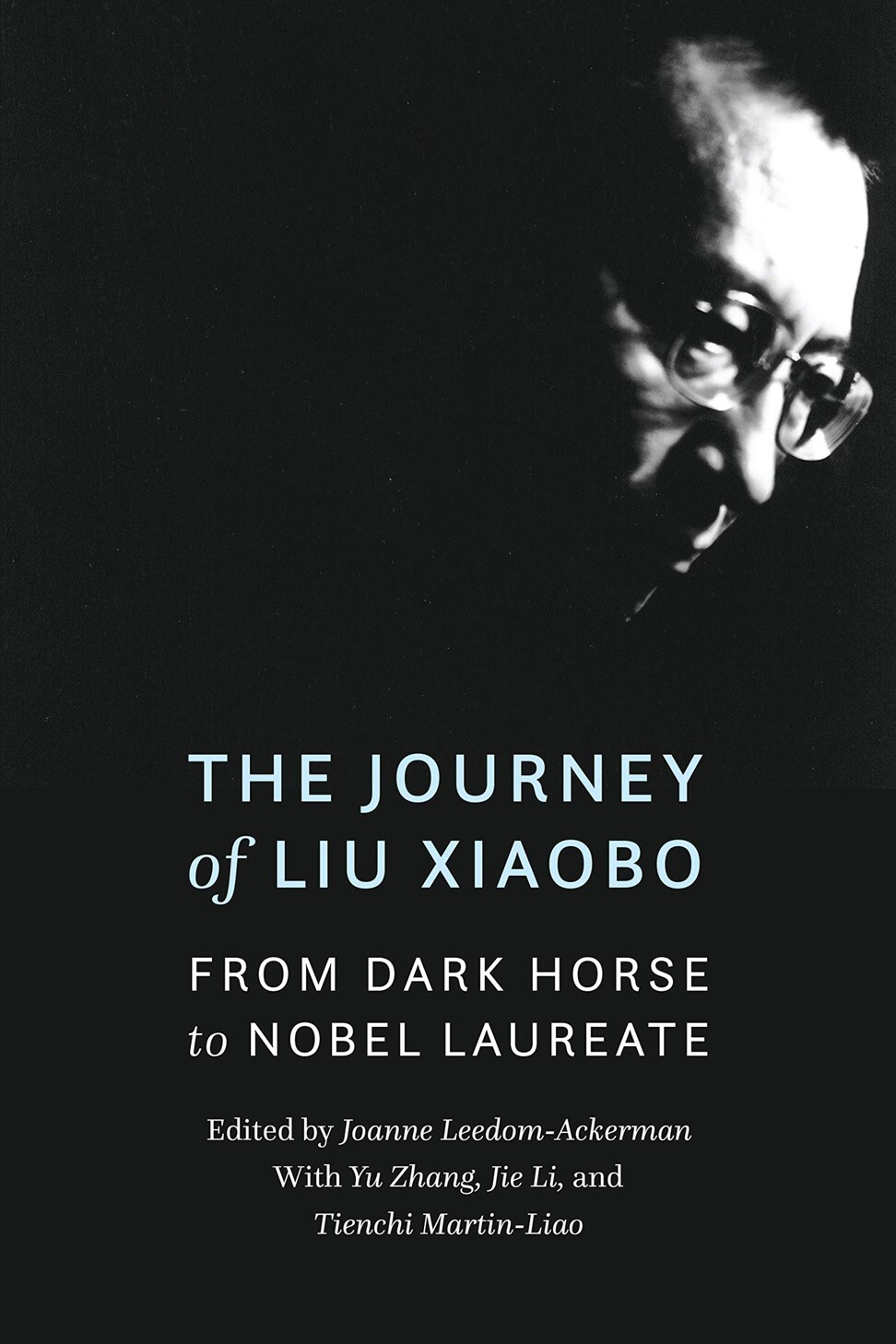

The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate

edited by Joanne Leedom-Ackerman with Yu Zhang and others

Potomac Books

4.5/5 stars

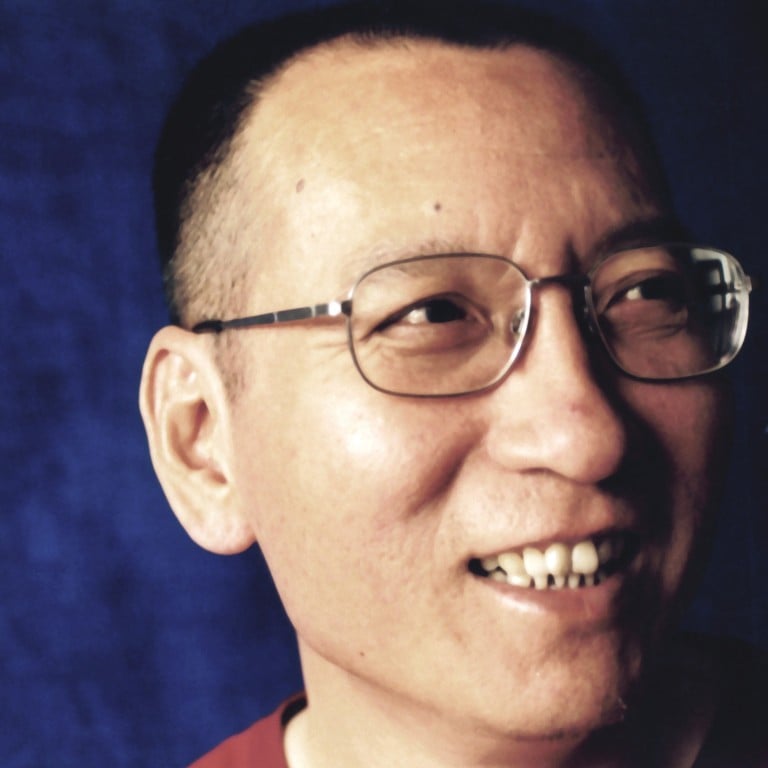

Towards the end of a book launch held in Taipei in July 2017, bestselling Chinese author and democracy advocate Yu Jie invoked a quote that was also the title of his latest work: “Take out a rib and use it as a torch.” Socrates had used these words, the author told the gathering, but Chinese dissident Liu Xiaobo had practised them throughout his life.

Yu describes the loss of his best friend and winner of the 2010 Nobel Peace Prize in an emotionally charged article included in The Journey of Liu Xiaobo: From Dark Horse to Nobel Laureate, a marvellous collection of 70 essays and reflections – and a few poems – by the late dissident’s friends, acquaintances and academic colleagues.

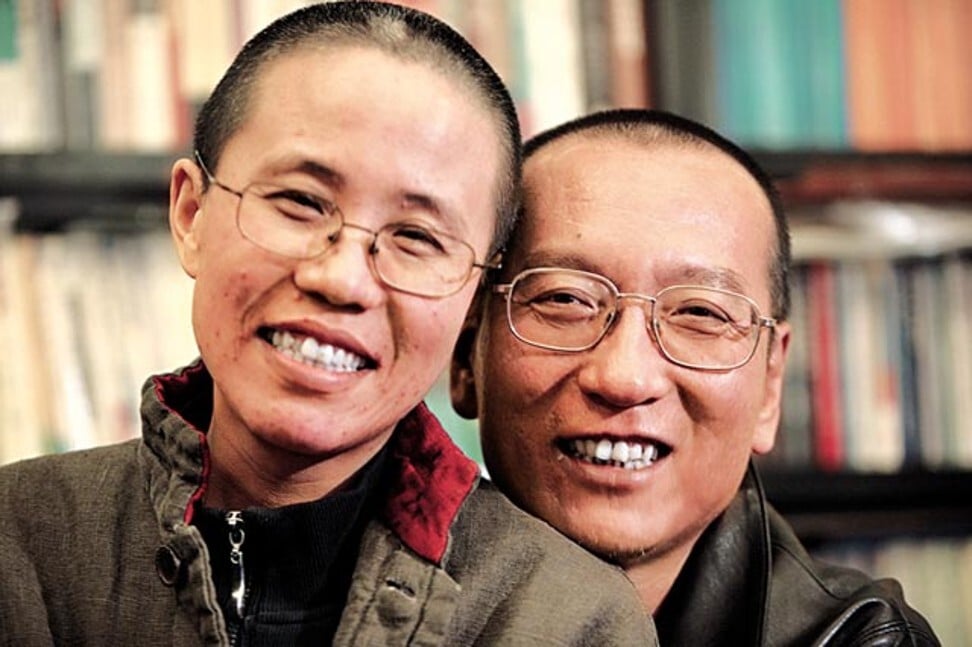

His friends believe Chinese authorities intentionally allowed his disease to fester for too long, apparently because they feared the influence of a dissident who had been awarded one of the world’s most prestigious prizes – Liu was the first Chinese citizen to win a Nobel Prize of any kind while still living in China.

The authorities ignored fervent appeals from his friends, family and admirers to allow Liu to travel overseas for treatment, prompting commentators to draw comparisons with the persecution of Carl von Ossietzky, a German journalist and writer who won the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize while in a Nazi concentration camp and died in a hospital a year and a half after being freed. (In contrast, Liu breathed his last in police custody.)

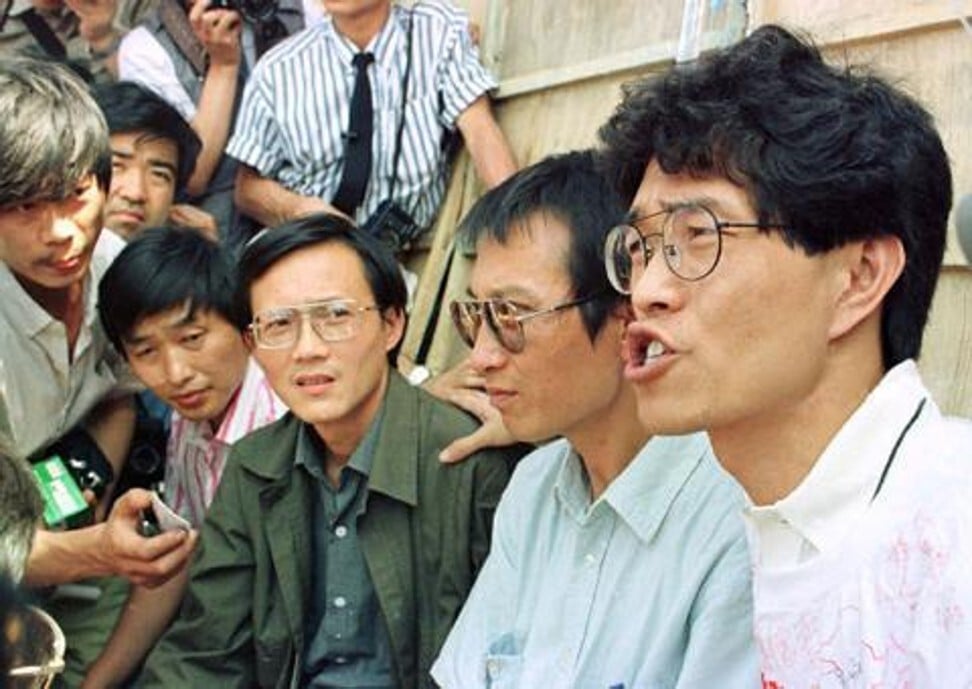

Liu spent the last 28 years of his life mostly in and out of prison, earning the moniker “the Nelson Mandela of China”. Chinese authorities labelled him a behind-the-scenes “black hand” of the 1989 “counter-revolutionary riot”, writes Teng Biao, a United States-based Chinese scholar and human rights lawyer in an elegiac essay titled “Liu Xiaobo’s Death as an Event of Human Spirit”.

Teng gained his initial understanding of Liu’s political views from just a few words of official propaganda aimed at rewriting the history of China’s pro-democracy movement. “That ‘counter-revolutionary riot’ was later called the ‘turmoil’, then the ‘political disturbance’ and then, in the end, it became a sensitive word,” he writes, adding: “‘Liu Xiaobo’ became a restricted area. His body disappeared again and again inside iron walls. His writing was heavily blocked by the Red Wall.”

Liu, who came from a scholarly family and taught Chinese literature at Beijing Normal University, was one of the main drafters and co-authors of Charter 08. A 2008 manifesto in the style of Czechoslovakia’s Charter 77, it called for political reform, human rights protection and gradual implementation of a constitutional democracy in China.

Initially sponsored by 303 intellectuals, activists and human rights defenders nationwide, the document gained more than 13,000 signatures as of 2017 – and it was clearly the reason why Liu was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

‘Liu Xiaobo’ became a restricted area. His body disappeared again and again inside iron walls. His writing was heavily blocked by the Red Wall

It is a cruel irony that Liu’s prison sentence, which was handed down on Christmas Day in 2009, evidently led to his Nobel Peace Prize the following year.

“At the Nobel banquet in December 2010, a member of the selection committee told me that her group had for years been wanting to find a Chinese winner for their prize and that the previous year’s events ‘made this finally seem the right time’,” Perry Link, an American sinologist and professor emeritus of Princeton University, writes in an essay titled “The Passion of Liu Xiaobo”.

Link adds that China’s president at the time, Hu Jintao, and his Politburo “were likely annoyed to realise (if they ever did) that their imprisonment of Liu helped pave the way to his award”.

Well before China’s 1989 democracy movement grabbed international headlines, Liu was already known as a “literary dark horse”, writes Yu Zhang, a Sweden-based Chinese scholar, in a brief biography of Liu in the book. Liu’s unconventional ideas and radical remarks, according to Yu, were often couched in language that was inappropriate if not outright offensive.

“The national inertia of Chinese intellectuals is even more deeply entrenched than that of the general public!” Yu quotes Liu as saying in an impromptu speech delivered at a 1986 symposium held by the Institute of Literature at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, in Beijing. “The development of Chinese culture has always restricted sensibility with rationality, and has framed the free development of individual consciousness within moral standards.”

By far the most controversial remark that Liu ever made came during a December 1988 interview with Emancipation Monthly, a Hong Kong publication later renamed Open Magazine. “It took a century of colonialism to make Hong Kong what it is today,” Liu was quoted as saying. “Given China’s size, it would need three centuries to become what Hong Kong is today. I even wonder if three centuries would be enough.”

“He took a ruthless and thoroughly negative attitude towards the Chinese literary tradition […] the Chinese philosophical tradition represented by Confucianism, the Chinese political tradition represented by absolute imperialism, and the contemporary political tradition represented by Mao Zedong and the Chinese Communist Party,” writes Yang Guang, a Hubei-based scholar and deputy secretary general of the Independent Chinese PEN Centre, which Liu co-founded in 2001.

The Liu Xiaobo of that time was not a genuine advocate of freedom and democracy but a radical proponent of blanket westernisation. “His remarks were similar to those of the Japanese enlightenment thinkers at the outset of Japan’s Meiji Restoration period, who advocated ‘breaking away from Asia and joining Europe’,” writes Yang.

“He even made ‘treasonous and heretical’ remarks such as, ‘If I could manage [foreign] languages well enough, I would have nothing to do with China’, and ‘If you say I’m a traitor, then I am’, which were simply the indignant outpouring of frenzied hatred due to the depths of his love for the nation.”

In fact, Yang clarifies, during the 1989 Tiananmen crisis, Liu, “for all his appearance of thoroughly detesting everything Chinese, didn’t take the opportunity to break off relations with China but rather put his life at risk for the cause of China’s human rights and democracy.

“Liu Xiaobo can be considered our generation’s most steadfast and determined and greatest patriot,” a latter-day Friedrich Nietzsche, “who expressed his extreme disappointment with history and current reality by declaring ‘God is dead’ and calling for ‘revaluation of all values’”.

One of the strengths of The Journey of Liu Xiaobo is the probity and conviction of its articles, all but five of which were translated from Chinese into English. Many of the authors didn’t just know Liu intimately but clearly display a deep knowledge of Chinese politics and culture.

A case in point is “Liu Xiaobo and His View of ‘No Enemies’”, an essay by Jin Zhong, the chief editor of Open Magazine, who carried out the 1988 interview with Liu. Alluding to a final statement in a Beijing court where, moments before being sentenced to 11 years in prison, Liu said, “I have no enemies,” Jin quotes the activist as elaborating: “Hatred only eats away at a person’s intelligence and conscience, and an enemy mentality can poison the spirit of an entire people […] I hope I can answer the regime’s enmity with utmost benevolence, and can use love to dissipate hate.”

Liu’s “No Enemies” concept, Jin believes, also offers a glimpse of his prediction of a free, democratic China.

“A constitutional democracy makes no distinction between the ‘enemy’ and us; this is where Liu Xiaobo transcended the mindset of his fellow citizens’,” writes Jin. “Essentially, this was not only his personal political belief but also his appeal to those in power: he pointed out that ‘the regime’s enemy mentality has pushed me into the defendant’s dock’, but the even deeper meaning was that a ‘life-and-death struggle has already caused rivers of bloodshed in our country’. Put down your butcher’s knives and don’t be an enemy of the people.”